There is an attitude for which my friends and I were for a long period rebuked and even reviled; and of which at the present period we are less likely than ever to repent. It was always called Anti-Semitism; but it was always much more true to call it Zionism. At any rate it was much nearer to the nature of the thing to call it Zionism, whether or no it can find its geographical concentration in Zion. The substance of this heresy was exceedingly simple. It consisted entirely in saying that Jews are Jews; and as a logical consequence that they are not Russians or Roumanians or Italians or Frenchmen or Englishmen. During the war the newspapers commonly referred to them as Russians; but the ritual wore so singularly thin that I remember one newspaper paragraph saying that the Russians in the East End complained of the food regulations, because their religion forbade them to eat pork. My own brief contact with the Greek priests of the Orthodox Church in Jerusalem did not permit me to discover any trace of this detail of their discipline; and even the Russian pilgrims were said to be equally negligent in the matter. The point for the moment, however, is that if I was violently opposed to anything, it was not to Jews, but to that sort of remark about Jews; or rather to the silly and craven fear of making it a remark about Jews. But my friends and I had in some general sense a policy in the matter; and it was in substance the desire to give Jews the dignity and status of a separate nation. We desired that in some fashion, and so far as possible, Jews should be represented by Jews, should live in a society of Jews, should be judged by Jews and ruled by Jews. I am an Anti-Semite if that is Anti-Semitism. It would seem more rational to call it Semitism.

Of this attitude, I repeat, I am now less likely than ever to repent. I have lived to see the thing that was dismissed as a fad discussed everywhere as a fact; and one of the most menacing facts of the age. I have lived to see people who accused me of Anti-Semitism become far more Anti-Semitic than I am or ever was. I have heard people talking with real injustice about the Jews, who once seemed to think it an injustice to talk about them at all. But, above all, I have seen with my own eyes wild mobs marching through a great city, raving not only against Jews, but against the English for identifying themselves with the Jews. I have seen the whole prestige of England brought into peril, merely by the trick of talking about two nations as if they were one. I have seen an Englishman arriving in Jerusalem with somebody he had been taught to regard as his fellow countryman and political colleague, and received as if he had come arm-in-arm with a flaming dragon. So do our frosty fictions fare when they come under that burning sun.

Twice in my life, and twice lately, I have seen a piece of English pedantry bring us within an inch of an enormous English peril. The first was when all the Victorian historians and philosophers had told us that our German cousin was a cousin german and even germane; something naturally near and sympathetic. That also was an identification; that also was an assimilation; that also was a union of hearts. For the second time in a few short years, English politicians and journalists have discovered the dreadful revenge of reality. To pretend that something is what it is not is business that can easily be fashionable and sometimes popular. But the thing we have agreed to regard as what it is not will always abruptly punish and pulverise us, merely by being what it is. For years we were told that the Germans were a sort of Englishman because they were Teutons; but it was all the worse for us when we found out what Teutons really were. For years we were told that Jews were a sort of Englishman because they were British subjects. It is all the worse for us now we have to regard them, not subjectively as subjects, but objectively as objects; as objects of a fierce hatred among the Moslems and the Greeks. We are in the absurd position of introducing to these people a new friend whom they instantly recognise as an old enemy. It is an absurd position because it is a false position; but it is merely the penalty of falsehood.

Whether this Eastern anger is reasonable or not may be discussed in a moment; but what is utterly unreasonable is not the anger but the astonishment; at least it is our astonishment at their astonishment. We might believe ourselves in the view that a Jew is an Englishman; but there was no reason why they should regard him as an Englishman, since they already recognised him as a Jew. This is the whole present problem of the Jew in Palestine; and it must be solved either by the logic of Zionism or the logic of purely English supremacy and, impartiality; and not by what seems to everybody in Palestine a monstrous muddle of the two. But of course it is not only the peril in Palestine that has made the realisation of the Jewish problem, which once suffered all the dangers of a fad, suffer the opposite dangers of a fashion. The same journalists who politely describe Jews as Russians are now very impolitely describing certain Russians who are Jews. Many who had no particular objection to Jews as Capitalists have a very great objection to them as Bolshevists. Those who had an innocent unconsciousness of the nationality of Eckstein, even when he called himself Eckstein, have managed to discover the nationality of Braunstein, even, when he calls, himself Trotsky. And much of this peril also might easily have been lessened, by the simple proposal to call men and things by their own names.

I will confess, however, that I have no very full sympathy with the new Anti-Semitism which is merely Anti-Socialism. There are good, honourable and magnanimous Jews of every type and rank, there are many to whom I am greatly attached among my own friends in my own rank; but if I have to make a general choice on a general chance among different types of Jews, I have much more sympathy with the Jew who is revolutionary than the Jew who is plutocratic. In other words, I have much more sympathy for the Israelite we are beginning to reject, than for the Israelite we have already accepted. I have more respect for him when he leads some sort of revolt, however narrow and anarchic, against the oppression of the poor, than when he is safe at the head of a great money-lending business oppressing the poor himself. It is not the poor aliens, but the rich aliens I wish we had excluded. I myself wholly reject Bolshevism, not because its actions are violent, but because its very thought is materialistic and mean. And if this preference is true even of Bolshevism, it is ten times truer of Zionism. It really seems to me rather hard that the full storm of fury should have burst about the Jews, at the very moment when some of them at least have felt the call of a far cleaner ideal; and that when we have tolerated their tricks with our country, we should turn on them precisely when they seek in sincerity for their own.

But in order to judge this Jewish possibility, we must understand more fully the nature of the Jewish problem. We must consider it from the start, because there are still many who do not know that there is a Jewish problem. That problem has its proof, of course, in the history of the Jew, and the fact that he came from the East. A Jew will sometimes complain of the injustice of describing him as a man of the East; but in truth another very real injustice may be involved in treating him as a man of the West. Very often even the joke against the Jew is rather a joke against those who have made the joke; that is, a joke against what they have made out of the Jew. This is true especially, for instance, of many points of religion and ritual. Thus we cannot help feeling, for instance, that there is something a little grotesque about the Hebrew habit of putting on a top-hat as an act of worship. It is vaguely mixed up with another line of humour, about another class of Jew, who wears a large number of hats; and who must not therefore be credited with an extreme or extravagant religious zeal, leading him to pile up a pagoda of hats towards heaven. To Western eyes, in Western conditions, there really is something inevitably fantastic about this formality of the synagogue. But we ought to remember that we have made the Western conditions which startle the Western eyes. It seems odd to wear a modern top-hat as if it were a mitre or a biretta; it seems quainter still when the hat is worn even for the momentary purpose of saying grace before lunch. It seems quaintest of all when, at some Jewish luncheon parties, a tray of hats is actually handed round, and each guest helps himself to a hat as a sort of hors d’oeuvre. All this could easily be turned into a joke; but we ought to realise that the joke is against ourselves. It is not merely we who make fun of it, but we who have made it funny. For, after all, nobody can pretend that this particular type of head-dress is a part of that uncouth imagery “setting painting and sculpture at defiance” which Renan remarked in the tradition of Hebrew civilisation. Nobody can say that a top-hat was among the strange symbolic utensils dedicated to the obscure service of the Ark; nobody can suppose that a top-hat descended from heaven among the wings and wheels of the flying visions of the Prophets. For this wild vision the West is entirely responsible. Europe has created the Tower of Giotto; but it has also created the topper. We of the West must bear the burden, as best we may, both of the responsibility and of the hat. It is solely the special type and shape of hat that makes the Hebrew ritual seem ridiculous. Performed in the old original Hebrew fashion it is not ridiculous, but rather if anything sublime. For the original fashion was an oriental fashion; and the Jews are orientals; and the mark of all such orientals is the wearing of long and loose draperies. To throw those loose draperies over the head is decidedly a dignified and even poetic gesture. One can imagine something like justice done to its majesty and mystery in one of the great dark drawings of William Blake. It may be true, and personally I think it is true, that the Hebrew covering of the head signifies a certain stress on the fear of God, which is the beginning of wisdom, while the Christian uncovering of the head suggests rather the love of God that is the end of wisdom. But this has nothing to do with the taste and dignity of the ceremony; and to do justice to these we must treat the Jew as an oriental; we must even dress him as an oriental.

I have only taken this as one working example out of many that would point to the same conclusion. A number of points upon which the unfortunate alien is blamed would be much improved if he were, not less of an alien, but rather more of an alien. They arise from his being too like us, and too little like himself. It is obviously the case, for instance, touching that vivid vulgarity in clothes, and especially the colours of clothes, with which a certain sort of Jews brighten the landscape or seascape at Margate or many holiday resorts. When we see a foreign gentleman on Brighton Pier wearing yellow spats, a magenta waistcoat, and an emerald green tie, we feel that he has somehow missed certain fine shades of social sensibility and fitness. It might considerably surprise the company on Brighton Pier, if he were to reply by solemnly unwinding his green necktie from round his neck, and winding it round his head. Yet the reply would be the right one; and would be equally logical and artistic. As soon as the green tie had become a green turban, it might look as appropriate and even attractive as the green turban of any pilgrim of Mecca or any descendant of Mahomet, who walks with a stately air through the streets of Jaffa or Jerusalem. The bright colours that make the Margate Jews hideous are no brighter than those that make the Moslem crowd picturesque. They are only worn in the wrong place, in the wrong way, and in conjunction with a type and cut of clothing that is meant to be more sober and restrained. Little can really be urged against him, in that respect, except that his artistic instinct is rather for colour than form, especially of the kind that we ourselves have labelled good form.

This is a mere symbol, but it is so suitable a symbol that I have often offered it symbolically as a solution of the Jewish problem. I have felt disposed to say: let all liberal legislation stand, let all literal and legal civic equality stand; let a Jew occupy any political or social position which he can gain in open competition; let us not listen for a moment to any suggestions of reactionary restrictions or racial privilege. Let a Jew be Lord Chief justice, if his exceptional veracity and reliability have clearly marked him out for that post. Let a Jew be Archbishop of Canterbury, if our national religion has attained to that receptive breadth that would render such a transition unobjectionable and even unconscious. But let there be one single-clause bill; one simple and sweeping law about Jews, and no other. Be it enacted, by the King’s Most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal and the Commons in Parliament assembled, that every Jew must be dressed like an Arab. Let him sit on the Woolsack, but let him sit there dressed as an Arab. Let him preach in St. Paul’s Cathedral, but let him preach there dressed as an Arab. It is not my point at present to dwell on the pleasing if flippant fancy of how much this would transform the political scene; of the dapper figure of Sir Herbert Samuel swathed as a Bedouin, or Sir Alfred Mond gaining a yet greater grandeur from the gorgeous and trailing robes of the East. If my image is quaint my intention is quite serious; and the point of it is not personal to any particular Jew. The point applies to any Jew, and to our own recovery of healthier relations with him. The point is that we should know where we are; and he would know where he is, which is in a foreign land.

This is but a parenthesis and a parable, but it brings us to the concrete controversial matter which is the Jewish problem. Only a few years ago it was regarded as a mark of a blood-thirsty disposition to admit that the Jewish problem was a problem, or even that the Jew was a Jew. Through much misunderstanding certain friends of mine and myself have persisted in disregarding the silence thus imposed; but facts have fought for us more effectively than words. By this time nobody is more conscious of the Jewish problem than the most intelligent and idealistic of the Jews. The folly of the fashion by which Jews often concealed their Jewish names, must surely be manifest by this time even to those who concealed them. To mention but one example of the way in which this fiction falsified the relations of everybody and everything, it is enough to note that it involved the Jews themselves in a quite new and quite needless unpopularity in the first years of the war. A poor little Jewish tailor, who called himself by a German name merely because he lived for a short time in a German town, was instantly mobbed in Whitechapel for his share in the invasion of Belgium. He was cross-examined about why he had damaged the tower of Rheims; and talked to as if he had killed Nurse Cavell with his own pair of shears. It was very unjust; quite as unjust as it would be to ask Bethmann-Hollweg why he had stabbed Eglon or hewn Agag in pieces. But it was partly at least the fault of the Jew himself, and of the whole of that futile and unworthy policy which had led him to call himself Bernstein when his name was Benjamin.

In such cases the Jews are accused of all sorts of faults they have not got; but there are faults that they have got. Some of the charges against them, as in the cases I have quoted concerning religious ritual and artistic taste, are due merely to the false light in which they are regarded. Other faults may also be due to the false position in which they are placed. But the faults exist; and nothing was ever more dangerous to everybody concerned than the recent fashion of denying or ignoring them. It was done simply by the snobbish habit of suppressing the experience and evidence of the majority of people, and especially of the majority of poor people. It was done by confining the controversy to a small world of wealth and refinement, remote from all the real facts involved. For the rich are the most ignorant people on earth, and the best that can be said for them, in cases like these, is that their ignorance often reaches the point of innocence.

I will take a typical case, which sums up the whole of this absurd fashion. There was a controversy in the columns of an important daily paper, some time ago, on the subject of the character of Shylock in Shakespeare. Actors and authors of distinction, including some of the most brilliant of living Jews, argued the matter from the most varied points of view. Some said that Shakespeare was prevented by the prejudices of his time from having a complete sympathy with Shylock. Some said that Shakespeare was only restrained by fear of the powers of his time from expressing his complete sympathy with Shylock. Some wondered how or why Shakespeare had got hold of such a queer story as that of the pound of flesh, and what it could possibly have to do with so dignified and intellectual a character as Shylock. In short, some wondered why a man of genius should be so much of an Anti-Semite, and some stoutly declared that he must have been a Pro-Semite. But all of them in a sense admitted that they were puzzled as to what the play was about. The correspondence filled column after column and went on for weeks. And from one end of that correspondence to the other, no human being even so much as mentioned the word “usury.” It is exactly as if twenty clever critics were set down to talk for a month about the play of Macbeth, and were all strictly forbidden to mention the word “murder.”

The play called The Merchant of Venice happens to be about usury, and its story is a medieval satire on usury. It is the fashion to say that it is a clumsy and grotesque story; but as a fact it is an exceedingly good story. It is a perfect and pointed story for its purpose, which is to convey the moral of the story. And the moral is that the logic of usury is in its nature at war with life, and might logically end in breaking into the bloody house of life. In other words, if a creditor can always claim a man’s tools or a man’s home, he might quite as justly claim one of his arms or legs. This principle was not only embodied in medieval satires but in very sound medieval laws, which set a limit on the usurer who was trying to take away a man’s livelihood, as the usurer in the play is trying to take away a man’s life. And if anybody thinks that usury can never go to lengths wicked enough to be worthy of so wild an image, then that person either knows nothing about it or knows too much. He is either one of the innocent rich who have never been the victims of money-lenders, or else one of the more powerful and influential rich who are money-lenders themselves.

All this, I say, is a fact that must be faced, but there is another side to the case, and it is this that the genius of Shakespeare discovered. What he did do, and what the medieval satirist did not do, was to attempt to understand Shylock; in the true sense to sympathise with Shylock the money-lender, as he sympathised with Macbeth the murderer. It was not to deny that the man was an usurer, but to assert that the usurer was a man. And the Elizabethan dramatist does make him a man, where the medieval satirist made him a monster. Shakespeare not only makes him a man but a perfectly sincere and self-respecting man. But the point is this: that he is a sincere man who sincerely believes in usury. He is a self-respecting man who does not despise himself for being a usurer. In one word, he regards usury as normal. In that word is the whole problem of the popular impression of the Jews. What Shakespeare suggested about the Jew in a subtle and sympathetic way, millions of plain men everywhere would suggest about him in a rough and ready way. Regarding the Jew in relation to his ideas about interest, they think either that he is simply immoral; or that if he is moral, then he has a different morality. There is a great deal more to be said about how far this is true, and about what are its causes and excuses if it is true. But it is an old story, surely, that the worst of all cures is to deny the disease.

To recognise the reality of the Jewish problem is very vital for everybody and especially vital for Jews. To pretend that there is no problem is to precipitate the expression of a rational impatience, which unfortunately can only express itself in the rather irrational form of Anti-Semitism. In the controversies of Palestine and Syria, for instance, it is very common to hear the answer that the Jew is no worse than the Armenian. The Armenian also is said to be unpopular as a money-lender and a mercantile upstart; yet the Armenian figures as a martyr for the Christian faith and a victim of the Moslem fury. But this is one of those arguments which really carry their own answer. It is like the sceptical saying that man is only an animal, which of itself provokes the retort, “What an animal!” The very similarity only emphasises the contrast. Is it seriously suggested that we can substitute the Armenian for the Jew in the study of a world-wide problem like that of the Jews? Could we talk of the competition of Armenians among Welsh shop-keepers, or of the crowd of Armenians on Brighton Parade? Can Armenian usury be a common topic of talk in a camp in California and in a club in Piccadilly? Does Shakespeare show us a tragic Armenian towering over the great Venice of the Renascence? Does Dickens show us a realistic Armenian teaching in the thieves’ kitchens of the slums? When we meet Mr. Vernon Vavasour, that brilliant financier, do we speculate on the probability of his really having an Armenian name to match his Armenian nose? Is it true, in short, that all sorts of people, from the peasants of Poland to the peasants of Portugal, can agree more or less upon the special subject of Armenia? Obviously it is not in the least true; obviously the Armenian question is only a local question of certain Christians, who may be more avaricious than other Christians. But it is the truth about the Jews. It is only half the truth, and one which by itself would be very unjust to the Jews. But it is the truth, and we must realise it as sharply and clearly as we can. The truth is that it is rather strange that the Jews should be so anxious for international agreements. For one of the few really international agreements is a suspicion of the Jews.

A more practical comparison would be one between the Jews and gipsies; for the latter at least cover several countries, and can be tested by the impressions of very different districts. And in some preliminary respects the comparison is really useful. Both races are in different ways landless, and therefore in different ways lawless. For the fundamental laws are land laws. In both cases a reasonable man will see reasons for unpopularity, without wishing to indulge any task for persecution. In both cases he will probably recognise the reality of a racial fault, while admitting that it may be largely a racial misfortune. That is to say, the drifting and detached condition may be largely the cause of Jewish usury or gipsy pilfering; but it is not common sense to contradict the general experience of gipsy pilfering or Jewish usury. The comparison helps us to clear away some of the cloudy evasions by which modern men have tried to escape from that experience. It is absurd to say that people are only prejudiced against the money methods of the Jews because the medieval church has left behind a hatred of their religion. We might as well say that people only protect the chickens from the gipsies because the medieval church undoubtedly condemned fortune-telling. It is unreasonable for a Jew to complain that Shakespeare makes Shylock and not Antonio the ruthless money-lender; or that Dickens makes Fagin and not Sikes the receiver of stolen goods. It is as if a gipsy were to complain when a novelist describes a child as stolen by the gipsies, and not by the curate or the mothers’ meeting. It is to complain of facts and probabilities. There may be good gipsies; there may be good qualities which specially belong to them as gipsies; many students of the strange race have, for instance, praised a certain dignity and self-respect among the women of the Romany. But no student ever praised them for an exaggerated respect for private property, and the whole argument about gipsy theft can be roughly repeated about Hebrew usury. Above all, there is one other respect in which the comparison is even more to the point. It is the essential fact of the whole business, that the Jews do not become national merely by becoming a political part of any nation. We might as well say that the gipsies had villas in Clapham, when their caravans stood on Clapham Common.

But, of course, even this comparison between the two wandering peoples fails in the presence of the greater problem. Here again even the attempt at a parallel leaves the primary thing more unique. The gipsies do not become municipal merely by passing through a number of parishes, and it would seem equally obvious that a Jew need not become English merely by passing through England on his way from Germany to America. But the gipsy not only is not municipal, but he is not called municipal. His caravan is not immediately painted outside with the number and name of 123 Laburnam Road, Clapham. The municipal authorities generally notice the wheels attached to the new cottage, and therefore do not fall into the error. The gipsy may halt in a particular parish, but he is not as a rule immediately made a parish councillor. The cases in which a travelling tinker has been suddenly made the mayor of an important industrial town must be comparatively rare. And if the poor vagabonds of the Romany blood are bullied by mayors and magistrates, kicked off the land by landlords, pursued by policemen and generally knocked about from pillar to post, nobody raises an outcry that they are the victims of religious persecution; nobody summons meetings in public halls, collects subscriptions or sends petitions to parliament; nobody threatens anybody else with the organised indignation of the gipsies all over the world. The case of the Jew in the nation is very different from that of the tinker in the town. The moral elements that can be appealed to are of a very different style and scale. No gipsies are millionaires.

In short, the Jewish problem differs from anything like the gipsy problem in two highly practical respects. First, the Jews already exercise colossal cosmopolitan financial power. And second, the modern societies they live in also grant them vital forms of national political power. Here the vagrant is already as rich as a miser and the vagrant is actually made a mayor. As will be seen shortly, there is a Jewish side of the story which leads really to the same ending of the story; but the truth stated here is quite independent of any sympathetic or unsympathetic view of the race in question. It is a question of fact, which a sensible Jew can afford to recognise, and which the most sensible Jews do very definitely recognise. It is really irrational for anybody to pretend that the Jews are only a curious sect of Englishmen, like the Plymouth Brothers or the Seventh Day Baptists, in the face of such a simple fact as the family of Rothschild. Nobody can pretend that such an English sect can establish five brothers, or even cousins, in the five great capitals of Europe. Nobody can pretend that the Seventh Day Baptists are the seven grandchildren of one grandfather, scattered systematically among the warring nations of the earth. Nobody thinks the Plymouth Brothers are literally brothers, or that they are likely to be quite as powerful in Paris or in Petrograd as in Plymouth.

The Jewish problem can be stated very simply after all. It is normal for the nation to contain the family. With the Jews the family is generally divided among the nations. This may not appear to matter to those who do not believe in nations, those who really think there ought not to be any nations. But I literally fail to understand anybody who does believe in patriotism thinking that this state of affairs can be consistent with it. It is in its nature intolerable, from a national standpoint, that a man admittedly powerful in one nation should be bound to a man equally powerful in another nation, by ties more private and personal even than nationality. Even when the purpose is not any sort of treachery, the very position is a sort of treason. Given the passionately patriotic peoples of the west of Europe especially, the state of things cannot conceivably be satisfactory to a patriot. But least of all can it conceivably be satisfactory to a Jewish patriot; by which I do not mean a sham Englishman or a sham Frenchman, but a man who is sincerely patriotic for the historic and highly civilised nation of the Jews.

For what may be criticised here as Anti-Semitism is only the negative side of Zionism. For the sake of convenience I have begun by stating it in terms of the universal popular impression which some call a popular prejudice. But such a truth of differentiation is equally true on both its different sides. Suppose somebody proposes to mix up England and America, under some absurd name like the Anglo-Saxon Empire. One man may say, “Why should the jolly English inns and villages be swamped by these priggish provincial Yankees?” Another may say, “Why should the real democracy of a young country be tied to your snobbish old squirarchy?” But both these views are only versions of the same view of a great American: “God never made one people good enough to rule another.”

The primary point about Zionism is that, whether it is right or wrong, it does offer a real and reasonable answer both to Anti-Semitism and to the charge of Anti-Semitism. The usual phrases about religious persecution and racial hatred are not reasonable answers, or answers at all. These Jews do not deny that they are Jews; they do not deny that Jews may be unpopular; they do not deny that there may be other than superstitious reasons for their unpopularity. They are not obliged to maintain that when a Piccadilly dandy talks about being in the hands of the Jews he is moved by the theological fanaticism that prevails in Piccadilly; or that when a silly youth on Derby Day says he was done by a dirty Jew, he is merely conforming to that Christian orthodoxy which is one of the strict traditions of the Turf. They are not, like some other Jews, forced to pay so extravagant a compliment to the Christian religion as to suppose it the ruling motive of half the discontented talk in clubs and public-houses, of nearly every business man who suspects a foreign financier, or nearly every working man who grumbles against the local pawn-broker. Religious mania, unfortunately, is not so common. The Zionists do not need to deny any of these things; what they offer is not a denial but a diagnosis and a remedy. Whether their diagnosis is correct, whether their remedy is practicable, we will try to consider later, with something like a fair summary of what is to be said on both sides. But their theory, on the face of it, is perfectly reasonable. It is the theory that any abnormal qualities in the Jews are due to the abnormal position of the Jews. They are traders rather than producers because they have no land of their own from which to produce, and they are cosmopolitans rather than patriots because they have no country of their own for which to be patriotic. They can no more become farmers while they are vagrant than they could have built the Temple of Solomon while they were building the Pyramids of Egypt. They can no more feel the full stream of nationalism while they wander in the desert of nomadism than they could bathe in the waters of Jordan while they were weeping by the waters of Babylon. For exile is the worst kind of bondage. In insisting upon that at least the Zionists have insisted upon a profound truth, with many applications to many other moral issues. It is true that for any one whose heart is set on a particular home or shrine, to be locked out is to be locked in. The narrowest possible prison for him is the whole world.

It will be well to notice briefly, however, how the principle applies to the two Anti-Semitic arguments already considered. The first is the charge of usury and unproductive loans, the second the charge either of treason or of unpatriotic detachment. The charge of usury is regarded, not unreasonably, as only a specially dangerous development of the general charge of uncreative commerce and the refusal of creative manual exercise; the unproductive loan is only a minor form of the unproductive labour. It is certainly true that the latter complaint is, if possible, commoner than the former, especially in comparatively simple communities like those of Palestine. A very honest Moslem Arab said to me, with a singular blend of simplicity and humour, “A Jew does not work; but he grows rich. You never see a Jew working; and yet they grow rich. What I want to know is, why do we not all do the same? Why do we not also do this and become rich?” This is, I need hardly say, an over-simplification. Jews often work hard at some things, especially intellectual things. But the same experience which tells us that we have known many industrious Jewish scholars, Jewish lawyers, Jewish doctors, Jewish pianists, chess-players and so on, is an experience which cuts both ways. The same experience, if carefully consulted, will probably tell us that we have not known personally many patient Jewish ploughmen, many laborious Jewish blacksmiths, many active Jewish hedgers and ditchers, or even many energetic Jewish hunters and fishermen. In short, the popular impression is tolerably true to life, as popular impressions very often are; though it is not fashionable to say so in these days of democracy and self-determination. Jews do not generally work on the land, or in any of the handicrafts that are akin to the land; but the Zionists reply that this is because it can never really be their own land. That is Zionism, and that has really a practical place in the past and future of Zion.

Patriotism is not merely dying for the nation. It is dying with the nation. It is regarding the fatherland not merely as a real resting-place like an inn, but as a final resting-place, like a house or even a grave. Even the most Jingo of the Jews do not feel like this about their adopted country; and I doubt if the most intelligent of the Jews would pretend that they did. Even if we can bring ourselves to believe that Disraeli lived for England, we cannot think that he would have died with her. If England had sunk in the Atlantic he would not have sunk with her, but easily floated over to America to stand for the Presidency. Even if we are profoundly convinced that Mr. Beit or Mr. Eckstein had patriotic tears in his eyes when he obtained a gold concession from Queen Victoria, we cannot believe that in her absence he would have refused a similar concession from the German Emperor. When the Jew in France or in England says he is a good patriot he only means that he is a good citizen, and he would put it more truly if he said he was a good exile. Sometimes indeed he is an abominably bad citizen, and a most exasperating and execrable exile, but I am not talking of that side of the case. I am assuming that a man like Disraeli did really make a romance of England, that a man like Dernburg did really make a romance of Germany, and it is still true that though it was a romance, they would not have allowed it to be a tragedy. They would have seen that the story had a happy ending, especially for themselves. These Jews would not have died with any Christian nation.

But the Jews did die with Jerusalem. That is the first and last great truth in Zionism. Jerusalem was destroyed and Jews were destroyed with it, men who cared no longer to live because the city of their faith had fallen. It may be questioned whether all the Zionists have all the sublime insanity of the Zealots. But at least it is not nonsense to suggest that the Zionists might feel like this about Zion. It is nonsense to suggest that they would ever feel like this about Dublin or Moscow. And so far at least the truth both in Semitism and Anti-Semitism is included in Zionism.

It is a commonplace that the infamous are more famous than the famous. Byron noted, with his own misanthropic moral, that we think more of Nero the monster who killed his mother than of Nero the noble Roman who defeated Hannibal. The name of Julian more often suggests Julian the Apostate than Julian the Saint; though the latter crowned his canonisation with the sacred glory of being the patron saint of inn-keepers. But the best example of this unjust historical habit is the most famous of all and the most infamous of all. If there is one proper noun which has become a common noun, if there is one name which has been generalised till it means a thing, it is certainly the name of Judas. We should hesitate perhaps to call it a Christian name, except in the more evasive form of Jude. And even that, as the name of a more faithful apostle, is another illustration of the same injustice; for, by comparison with the other, Jude the faithful might almost be called Jude the obscure. The critic who said, whether innocently or ironically, “What wicked men these early Christians were!” was certainly more successful in innocence than in irony; for he seems to have been innocent or ignorant of the whole idea of the Christian communion. Judas Iscariot was one of the very earliest of all possible early Christians. And the whole point about him was that his hand was in the same dish; the traitor is always a friend, or he could never be a foe. But the point for the moment is merely that the name is known everywhere merely as the name of a traitor. The name of Judas nearly always means Judas Iscariot; it hardly ever means Judas Maccabeus. And if you shout out “Judas” to a politician in the thick of a political tumult, you will have some difficulty in soothing him afterwards, with the assurance that you had merely traced in him something of that splendid zeal and valour which dragged down the tyranny of Antiochus, in the day of the great deliverance of Israel.

Those two possible uses of the name of Judas would give us yet another compact embodiment of the case for Zionism. Numberless international Jews have gained the bad name of Judas, and some have certainly earned it. If you have gained or earned the good name of Judas, it can quite fairly and intelligently be affirmed that this was not the fault of the Jews, but of the peculiar position of the Jews. A man can betray like Judas Iscariot in another man’s house; but a man cannot fight like Judas Maccabeus for another man’s temple. There is no more truly rousing revolutionary story amid all the stories of mankind, there is no more perfect type of the element of chivalry in rebellion, than that magnificent tale of the Maccabee who stabbed from underneath the elephant of Antiochus and died under the fall of that huge and living castle. But it would be unreasonable to ask Mr. Montagu to stick a knife into the elephant on which Lord Curzon, let us say, was riding in all the pomp of Asiatic imperialism. For Mr. Montagu would not be liberating his own land; and therefore he naturally prefers to interest himself either in operations in silver or in somewhat slower and less efficient methods of liberation. In short, whatever we may think of the financial or social services such as were rendered to England in the affair of Marconi, or to France in the affair of Panama, it must be admitted that these exhibit a humbler and more humdrum type of civic duty, and do not remind us of the more reckless virtues of the Maccabees or the Zealots. A man may be a good citizen of anywhere, but he cannot be a national hero of nowhere; and for this particular type of patriotic passion it is necessary to have a patria. The Zionists therefore are maintaining a perfectly reasonable proposition, both about the charge of usury and the charge of treason, if they claim that both could be cured by the return to a national soil as promised in Zionism.

Unfortunately they are not always reasonable about their own reasonable proposition. Some of them have a most unlucky habit of ignoring, and therefore implicitly denying, the very evil that they are wisely trying to cure. I have already remarked this irritating innocence in the first of the two questions; the criticism that sees everything in Shylock except the point of him, or the point of his knife. How in the politics of Palestine at this moment this first question is in every sense the primary question. Palestine has hardly as yet a patriotism to be betrayed; but it certainly has a peasantry to be oppressed, and especially to be oppressed as so many peasantries have been with usury and forestalling. The Syrians and Arabs and all the agricultural and pastoral populations of Palestine are, rightly or wrongly, alarmed and angered at the advent of the Jews to power; for the perfectly practical and simple reason of the reputation which the Jews have all over the world. It is really ridiculous in people so intelligent as the Jews, and especially so intelligent as the Zionists, to ignore so enormous and elementary a fact as that reputation and its natural results. It may or may not in this case be unjust; but in any case it is not unnatural. It may be the result of persecution, but it is one that has definitely resulted. It may be the consequence of a misunderstanding; but it is a misunderstanding that must itself be understood. Rightly or wrongly, certain people in Palestine fear the coming of the Jews as they fear the coming of the locusts; they regard them as parasites that feed on a community by a thousand methods of financial intrigue and economic exploitation. I could understand the Jews indignantly denying this, or eagerly disproving it, or best of all, explaining what is true in it while exposing what is untrue. What is strange, I might almost say weird, about the attitude of some quite intelligent and sincere Zionists, is that they talk, write and apparently think as if there were no such thing in the world.

I will give one curious example from one of the best and most brilliant of the Zionists. Dr. Weizmann is a man of large mind and human sympathies; and it is difficult to believe that any one with so fine a sense of humanity can be entirely empty of anything like a sense of humour. Yet, in the middle of a very temperate and magnanimous address on “Zionist Policy,” he can actually say a thing like this, “The Arabs need us with our knowledge, and our experience and our money. If they do not have us they will fall into the hands of others, they will fall among sharks.” One is tempted for the moment to doubt whether any one else in the world could have said that, except the Jew with his strange mixture of brilliancy and blindness, of subtlety and simplicity. It is much as if President Wilson were to say, “Unless America deals with Mexico, it will be dealt with by some modern commercial power, that has trust-magnates and hustling millionaires.” But would President Wilson say it? It is as if the German Chancellor had said, “We must rush to the rescue of the poor Belgians, or they may be put under some system with a rigid militarism and a bullying bureaucracy.” But would even a German Chancellor put it exactly like that? Would anybody put it in the exact order of words and structure of sentence in which Dr. Weizmann has put it? Would even the Turks say, “The Armenians need us with our order and our discipline and our arms. If they do not have us they will fall into the hands of others, they will perhaps be in danger of massacres.” I suspect that a Turk would see the joke, even if it were as grim a joke as the massacres themselves. If the Zionists wish to quiet the fears of the Arabs, surely the first thing to do is to discover what the Arabs are afraid of. And very little investigation will reveal the simple truth that they are very much afraid of sharks; and that in their book of symbolic or heraldic zoology it is the Jew who is adorned with the dorsal fin and the crescent of cruel teeth. This may be a fairy-tale about a fabulous animal; but it is one which all sorts of races believe, and certainly one which these races believe.

But the case is yet more curious than that. These simple tribes are afraid, not only of the dorsal fin and dental arrangements which Dr. Weizmann may say (with some justice) that he has not got; they are also afraid of the other things which he says he has got. They may be in error, at the first superficial glance, in mistaking a respectable professor for a shark. But they can hardly be mistaken in attributing to the respectable professor what he himself considers as his claims to respect. And as the imagery about the shark may be too metaphorical or almost mythological, there is not the smallest difficulty in stating in plain words what the Arabs fear in the Jews. They fear, in exact terms, their knowledge and their experience and their money. The Arabs fear exactly the three things which he says they need. Only the Arabs would call it a knowledge of financial trickery and an experience of political intrigue, and the power given by hoards of money not only of their own but of other peoples. About Dr. Weizmann and the true Zionists this is self-evidently unjust; but about Jewish influence of the more visible and vulgar kind it has to be proved to be unjust. Feeling as I do the force of the real case for Zionism, I venture most earnestly to implore the Jews to disprove it, and not to dismiss it. But above all I implore them not to be content with assuring us again and again of their knowledge and their experience and their money. That is what people dread like a pestilence or an earthquake; their knowledge and their experience and their money. It is needless for Dr. Weizmann to tell us that he does not desire to enter Palestine like a Junker or drive thousands of Arabs forcibly out of the land; nobody supposes that Dr. Weizmann looks like a Junker; and nobody among the enemies of the Jews says that they have driven their foes in that fashion since the wars with the Canaanites. But for the Jews to reassure us by insisting on their own economic culture or commercial education is exactly like the Junkers reassuring us by insisting on the unquestioned supremacy of their Kaiser or the unquestioned obedience of their soldiers. Men bar themselves in their houses, or even hide themselves in their cellars, when such virtues are abroad in the land.

In short the fear of the Jews in Palestine, reasonable or unreasonable, is a thing that must be answered by reason. It is idle for the unpopular thing to answer with boasts, especially boasts of the very quality that makes it unpopular. But I think it could be answered by reason, or at any rate tested by reason; and the tests by consideration. The principle is still as stated above; that the tests must not merely insist on the virtues the Jews do show, but rather deal with the particular virtues which they are generally accused of not showing. It is necessary to understand this more thoroughly than it is generally understood, and especially better than it is usually stated in the language of fashionable controversy. For the question involves the whole success or failure of Zionism. Many of the Zionists know it; but I rather doubt whether most of the Anti-Zionists know that they know it. And some of the phrases of the Zionists, such as those that I have noted, too often tend to produce the impression that they ignore when they are not ignorant. They are not ignorant; and they do not ignore in practice; even when an intellectual habit makes them seem to ignore in theory. Nobody who has seen a Jewish rural settlement, such as Rishon, can doubt that some Jews are sincerely filled with the vision of sitting under their own vine and fig-tree, and even with its accompanying lesson that it is first necessary to grow the fig-tree and the vine.

The true test of Zionism may seem a topsy-turvy test. It will not succeed by the number of successes, but rather by the number of failures, or what the world (and certainly not least the Jewish world) has generally called failures. It will be tested, not by whether Jews can climb to the top of the ladder, but by whether Jews can remain at the bottom; not by whether they have a hundred arts of becoming important, but by whether they have any skill in the art of remaining insignificant. It is often noted that the intelligent Israelite can rise to positions of power and trust outside Israel, like Witte in Russia or Rufus Isaacs in England. It is generally bad, I think, for their adopted country; but in any case it is no good for the particular problem of their own country. Palestine cannot have a population of Prime Ministers and Chief Justices; and if those they rule and judge are not Jews, then we have not established a commonwealth but only an oligarchy. It is said again that the ancient Jews turned their enemies into hewers of wood and drawers of water. The modern Jews have to turn themselves into hewers of wood and drawers of water. If they cannot do that, they cannot turn themselves into citizens, but only into a kind of alien bureaucrats, of all kinds the most perilous and the most imperilled. Hence a Jewish state will not be a success when the Jews in it are successful, or even when the Jews in it are statesmen. It will be a success when the Jews in it are scavengers, when the Jews in it are sweeps, when they are dockers and ditchers and porters and hodmen. When the Zionist can point proudly to a Jewish navvy who has not risen in the world, an under-gardener who is not now taking his ease as an upper-gardener, a yokel who is still a yokel, or even a village idiot at least sufficiently idiotic to remain in his village, then indeed the world will come to blow the trumpets and lift up the heads of the everlasting gates; for God will have turned the captivity of Zion.

Zionists of whose sincerity I am personally convinced, and of whose intelligence anybody would be convinced, have told me that there really is, in places like Rishon, something like a beginning of this spirit; the love of the peasant for his land. One lady, even in expressing her conviction of it, called it “this very un-Jewish characteristic.” She was perfectly well aware both of the need of it in the Jewish land, and the lack of it in the Jewish race. In short she was well aware of the truth of that seemingly topsy-turvy test I have suggested; that of whether men are worthy to be drudges. When a humorous and humane Jew thus accepts the test, and honestly expects the Jewish people to pass it, then I think the claim is very serious indeed, and one not lightly to be set aside. I do certainly think it a very serious responsibility under the circumstances to set it altogether aside. It is our whole complaint against the Jew that he does not till the soil or toil with the spade; it is very hard on him to refuse him if he really says, “Give me a soil and I will till it; give me a spade and I will use it.” It is our whole reason for distrusting him that he cannot really love any of the lands in which he wanders; it seems rather indefensible to be deaf to him if he really says, “Give me a land and I will love it.” I would certainly give him a land or some instalment of the land, (in what general sense I will try to suggest a little later) so long as his conduct on it was watched and tested according to the principles I have suggested. If he asks for the spade he must use the spade, and not merely employ the spade, in the sense of hiring half a hundred men to use spades. If he asks for the soil he must till the soil; that is he must belong to the soil and not merely make the soil belong to him. He must have the simplicity, and what many would call the stupidity of the peasant. He must not only call a spade a spade, but regard it as a spade and not as a speculation. By some true conversion the urban and modern man must be not only on the soil, but of the soil, and free from our urban trick of inventing the word dirt for the dust to which we shall return. He must be washed in mud, that he may be clean.

How far this can really happen it is very hard for anybody, especially a casual visitor, to discover in the present crisis. It is admitted that there is much Arab and Syrian labour employed; and this in itself would leave all the danger of the Jew as a mere capitalist. The Jews explain it, however, by saying that the Arabs will work for a lower wage, and that this is necessarily a great temptation to the struggling colonists. In this they may be acting naturally as colonists, but it is none the less clear that they are not yet acting literally as labourers. It may not be their fault that they are not proving themselves to be peasants; but it is none the less clear that this situation in itself does not prove them to be peasants. So far as that is concerned, it still remains to be decided finally whether a Jew will be an agricultural labourer, if he is a decently paid agricultural labourer. On the other hand, the leaders of these local experiments, if they have not yet shown the higher materialism of peasants, most certainly do not show the lower materialism of capitalists. There can be no doubt of the patriotic and even poetic spirit in which many of them hope to make their ancient wilderness blossom like the rose. They at least would still stand among the great prophets of Israel, and none the less though they prophesied in vain.

I have tried to state fairly the case for Zionism, for the reason already stated; that I think it intellectually unjust that any attempt of the Jews to regularise their position should merely be rejected as one of their irregularities. But I do not disguise the enormous difficulties of doing it in the particular conditions Of Palestine. In fact the greatest of the real difficulties of Zionism is that it has to take place in Zion. There are other difficulties, however, which when they are not specially the fault of Zionists are very much the fault of Jews. The worst is the general impression of a business pressure from the more brutal and businesslike type of Jew, which arouses very violent and very just indignation. When I was in Jerusalem it was openly said that Jewish financiers had complained of the low rate of interest at which loans were made by the government to the peasantry, and even that the government had yielded to them. If this were true it was a heavier reproach to the government even than to the Jews. But the general truth is that such a state of feeling seems to make the simple and solid patriotism of a Palestinian Jewish nation practically impossible, and forces us to consider some alternative or some compromise. The most sensible statement of a compromise I heard among the Zionists was suggested to me by Dr. Weizmann, who is a man not only highly intelligent but ardent and sympathetic. And the phrase he used gives the key to my own rough conception of a possible solution, though he himself would probably, not accept that solution.

Dr. Weizmann suggested, if I understood him rightly, that he did not think Palestine could be a single and simple national territory quite in the sense of France; but he did not see why it should not be a commonwealth of cantons after the manner of Switzerland. Some of these could be Jewish cantons, others Arab cantons, and so on according to the type of population. This is in itself more reasonable than much that is suggested on the same side; but the point of it for my own purpose is more particular. This idea, whether it correctly represents Dr. Weizmann’s meaning or no, clearly involves the abandonment of the solidarity of Palestine, and tolerates the idea of groups of Jews being separated from each other by populations of a different type. Now if once this notion be considered admissible, it seems to me capable of considerable extension. It seems possible that there might be not only Jewish cantons in Palestine but Jewish cantons outside Palestine, Jewish colonies in suitable and selected places in adjacent parts or in many other parts of the world. They might be affiliated to some official centre in Palestine, or even in Jerusalem, where there would naturally be at least some great religious headquarters of the scattered race and religion. The nature of that religious centre it must be for Jews to decide; but I think if I were a Jew I would build the Temple without bothering about the site of the Temple. That they should have the old site, of course, is not to be thought of; it would raise a Holy War from Morocco to the marches of China. But seeing that some of the greatest of the deeds of Israel were done, and some of the most glorious of the songs of Israel sung, when their only temple was a box carried about in the desert, I cannot think that the mere moving of the situation of the place of sacrifice need even mean so much to that historic tradition as it would to many others. That the Jews should have some high place of dignity and ritual in Palestine, such as a great building like the Mosque of Omar, is certainly right and reasonable; for upon no theory can their historic connection be dismissed. I think it is sophistry to say, as do some Anti-Semites, that the Jews have no more right there than the Jebusites. If there are Jebusites they are Jebusites without knowing it. I think it sufficiently answered in the fine phrase of an English priest, in many ways more Anti-Semitic than I: “The people that remembers has a right.” The very worst of the Jews, as well as the very best, do in some sense remember. They are hated and persecuted and frightened into false names and double lives; but they remember. They lie, they swindle, they betray, they oppress; but they remember. The more we happen to hate such elements among the Hebrews the more we admire the manly and magnificent elements among the more vague and vagrant tribes of Palestine, the more we must admit that paradox. The unheroic have the heroic memory; and the heroic people have no memory.

But whatever the Jewish nation might wish to do about a national shrine or other supreme centre, the suggestion for the moment is that something like a Jewish territorial scheme might really be attempted, if we permit the Jews to be scattered no longer as individuals but as groups. It seems possible that by some such extension of the definition of Zionism we might ultimately overcome even the greatest difficulty of Zionism, the difficulty of resettling a sufficient number of so large a race on so small a land. For if the advantage of the ideal to the Jews is to gain the promised land, the advantage to the Gentiles is to get rid of the Jewish problem, and I do not see why we should obtain all their advantage and none of our own. Therefore I would leave as few Jews as possible in other established nations, and to these I would give a special position best described as privilege; some sort of self-governing enclave with special laws and exemptions; for instance, I would certainly excuse them from conscription, which I think a gross injustice in their case. [Footnote: Of course the privileged exile would also lose the rights of a native.] A Jew might be treated as respectfully as a foreign ambassador, but a foreign ambassador is a foreigner. Finally, I would give the same privileged position to all Jews everywhere, as an alternative policy to Zionism, if Zionism failed by the test I have named; the only true and the only tolerable test; if the Jews had not so much failed as peasants as succeeded as capitalists.

There is one word to be added; it will be noted that inevitably and even against some of my own desires, the argument has returned to that recurrent conclusion, which was found in the Roman Empire and the Crusades. The European can do justice to the Jew; but it must be the European who does it. Such a possibility as I have thrown out, and any other possibility that any one can think of, becomes at once impossible without some idea of a general suzerainty of Christendom over the lands of the Moslem and the Jew. Personally, I think it would be better if it were a general suzerainty of Christendom, rather than a particular supremacy of England. And I feel this, not from a desire to restrain the English power, but rather from a desire to defend it. I think there is not a little danger to England in the diplomatic situation involved; but that is a diplomatic question that it is neither within my power or duty to discuss adequately. But if I think it would be wiser for France and England together to hold Syria and Palestine together rather than separately, that only completes and clinches the conclusion that has haunted me, with almost uncanny recurrence, since I first saw Jerusalem sitting on the hill like a turreted town in England or in France; and for one moment the dark dome of it was again the Templum Domini, and the tower on it was the Tower of Tancred.

Anyhow with the failure of Zionism would fall the last and best attempt at a rationalistic theory of the Jew. We should be left facing a mystery which no other rationalism has ever come so near to providing within rational cause and cure. Whatever we do, we shall not return to that insular innocence and comfortable unconsciousness of Christendom, in which the Victorian agnostics could suppose that the Semitic problem was a brief medieval insanity. In this as in greater things, even if we lost our faith we could not recover our agnosticism. We can never recover agnosticism, any more than any other kind of ignorance. We know that there is a Jewish problem; we only hope that there is a Jewish solution. If there is not, there is no other. We cannot believe again that the Jew is an Englishman with certain theological theories, any more than we can believe again any other part of the optimistic materialism whose temple is the Albert Memorial. A scheme of guilds may be attempted and may be a failure; but never again can we respect mere Capitalism for its success. An attack may be made on political corruption, and it may be a failure; but never again can we believe that our politics are not corrupt. And so Zionism may be attempted and may be a failure; but never again can we ourselves be at ease in Zion. Or rather, I should say, if the Jew cannot be at ease in Zion we can never again persuade ourselves that he is at ease out of Zion. We can only salute as it passes that restless and mysterious figure, knowing at last that there must be in him something mystical as well as mysterious; that whether in the sense of the sorrows of Christ or of the sorrows of Cain, he must pass by, for he belongs to God.

This is an excerpt from G.K. Chesterton’s The New Jerusalem, published in 1920.

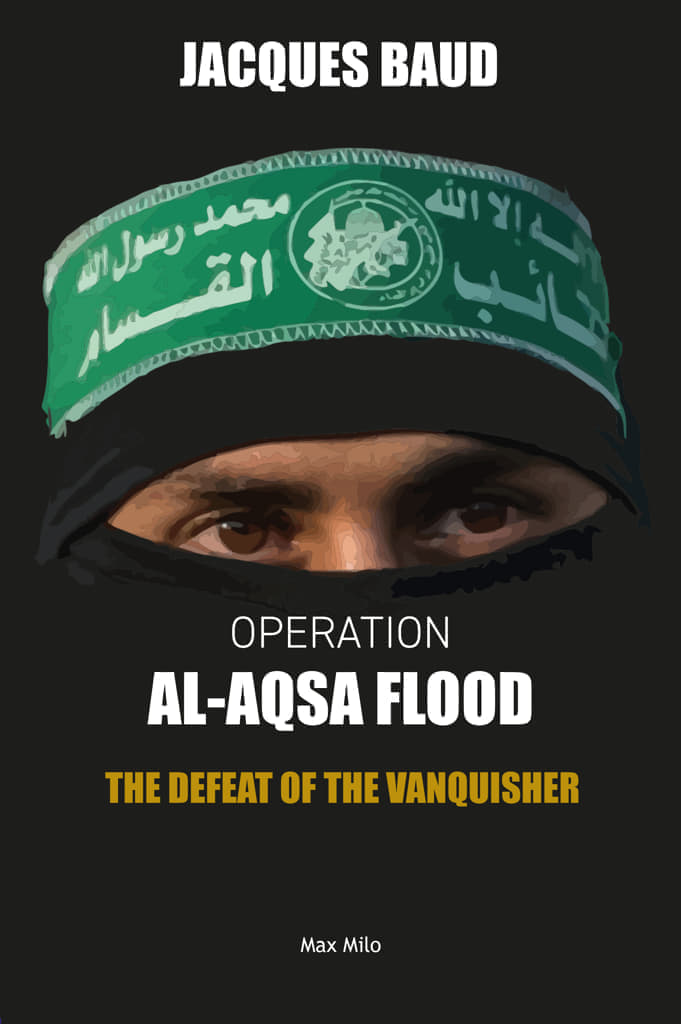

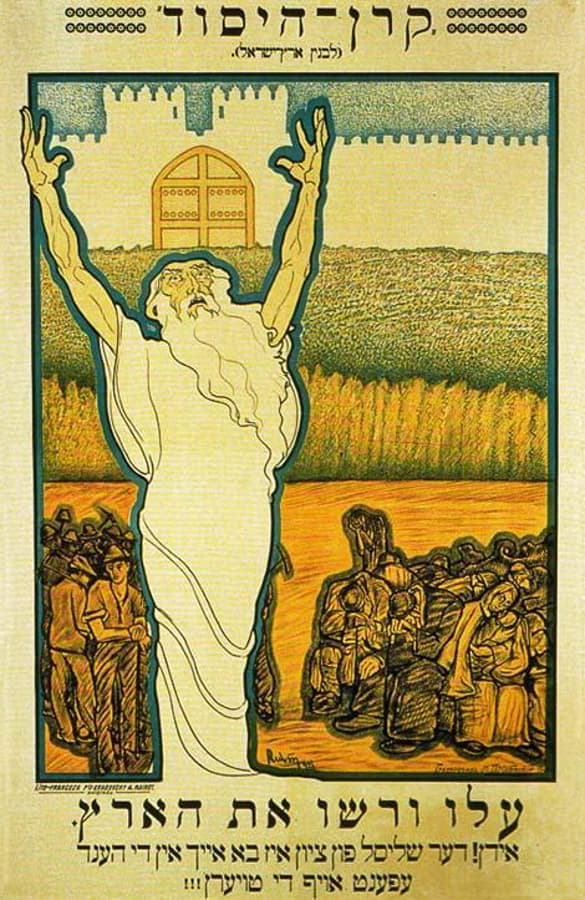

Featured: Build the Jewish homeland now. Palestine restoration fund $3,000,000. American Zionist poster, by Mitchell Loeb; published in 1919.