The final phase of WWI was especially bitter and cruel, not only for the grimness of the fight between exhausted warring parties (except one, the US), but also because it became clear that alliance against the Central Powers was a mere façade. The growing Allied division emerged with a peculiar stance toward one enemy, the Ottoman Empire and a (former) ally, Russia.

And in this light, the year 1918 could be considered not only the year of the end of the war, but the beginning of a new era, marked by new dynamics and an attempt to reaffirm the old power structures.

The Allies approach was the re-proposition of “playbook” actions, which had always dominated the policies, mainly of Great Britain and France, since the 19th century, toward these two entities. And to them, with different motivations, may be added Italy, US, Japan, Serbia (with the new formation of Croatia-Slovenia), Greece, Romania, Czechoslovakia and Poland. Thus, behind the mask of a cohesive policy, the main target was the demolition and partition, among the winners, of the Ottoman Empire and the re-establishment of a weakened Russia; and, where this was not possible, replicating the planned fate for the Ottomans with the establishment of a galaxy of puppet states.

The strategic target of both Paris and London was multifold: extend their own area of influence (directly and/or indirectly), push back any threat against their own national strategic interests, and stand in front of their allies, especially if minor ones, with an eye on the growing polarization with Italy, especially by France. In this gigantic plan, the personalities of Lloyd George, Churchill and Clemenceau emerged as dominant; and perhaps, like never before, the political use of military force.

The level of Allied forces deployed in the two areas, at least by Western standards, were limited in comparison with the millions of men deployed on the different fronts of WWI. But they were highly influential and played a decisive political role, though a small combat role.

After The “Garden Of Salonika

The fighting along the Macedonian Front in September 1918 might not be as well-known as the Somme, Ypres or Verdun (and certainly less bloody), but in terms of delivering the fatal blow to the German war machine, it was unsurpassed. “It was upon this much-abused front that the final collapse of the Central Empires first began,” Winston Churchill wrote.

Controversy had marked the life of the Allied “Armée d’Orient” ever since it began deploying three years earlier through Salonika, the Greek port city that provided the southern gateway to the Balkans, and after the disastrous French-British attempt to take by force the Straits of Dardanelles which sought to blow up the Ottoman Empire and provide support to Russia. The Allies had great difficulties facing the Germans and the Austro-Hungarians on the Eastern front.

The force (consisting of 600,000 men), formally under French command, included French, British, Serbian, Italian, Montenegrin and Russian contingents; added later were Greek and pro-Entente Albanian units. The management of this army persistently reflected the divergent objectives of the participants.

For example, the British contingent constantly tried to minimize the impact of the French command and directives. Also among the French-Italian contingents, the relations were at best controversial, and the collapse of the Central Powers, following the attack in September 1918, underlined the fault-lines among the Allies, not only political but also militarily.

British troops, immediately after the ceasefire, were sent in to secure the Turkish straits; the Italians went to protect Albania; and the French remained committed to their staunch support of Serbs, with the aim of setting up a South pan-Slavic state in the Western Balkans, under the influence of Paris, and initially also with Greece.

After a visit by Talaat Pasha, the Grand Vizir, to other Central Powers capitals in September 1918, Constantinople realized that there was no hope to win the war. On 13 October, Talaat and the government resigned. Ahmed Izzet Pasha was appointed as Grand Vizir and two days later, he sent the captured British General Charles Vere Ferrers Townshend to the Allies to seek terms for an armistice.

London interpreted that to mean that Britain would conduct the negotiations alone. As of today, the motives of this are not entirely clear, whether it was the sincere British interpretation of the alliance terms; or fears that the French would insist on over-harsh demands and foil a treaty; or, again, there was a desire to cut the French out of territorial ambitions promised by the Sykes-Picot agreement.

Townshend also indicated that the Ottomans preferred to deal with the British; he did not know about the contact with America, or that Talaat had sent an emissary to the French as well; but that emissary had been slower to respond.

The British cabinet empowered Admiral Calthorpe to conduct the negotiations with an explicit exclusion of the French. The negotiations began on 27 October on board of HMS Agamemnon. The British refused to admit to the talks the French Vice-Admiral Jean Amet, the senior French naval officer in the area, despite his desire to join. The Ottoman delegation, headed by Navy Minister Rauf Bey, indicated that this was acceptable, as they were accredited only to the British, not the French (and even less, to the Italian, Greeks, and Serbs).

The French were certainly displeased, and the French Premier Georges Clemenceau, the “Tiger,” complained about British unilateral decisions in so important a matter. Lloyd George countered that the French had the same approach in the Armistice of Salonica, which had been negotiated by French General Franchet d’Esperey, without consultations with the commanders of the other Allied contingents, while Great Britain (and Tsarist Russia) had committed the most troops to the campaign against the Ottoman Empire on different fronts (the Palestine, Mesopotamia, Arabia Peninsula and Caucasus fronts).

As part of the armistice’s conditions, the Ottomans surrendered their remaining garrisons outside Anatolia and granted the Allies the right to occupy the forts controlling the Straits of the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus, as well as any Ottoman territory, “in case of disorder,” or if a threat to security occured. Later, this vague and obscure clause was widely used by the Allies for their massive interference in Turkish affairs The Ottoman forces were demobilized, and all ports, railways and other strategic points were made available for Alled use. In the Caucasus, the Ottomans had to retreat to pre-war borders with the Russian Empire. Following this armistice, the occupation of Constantinople and the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire started.

Thereafter, it took 15 months of tough negotiations among the Allies (Britain, France and Italy) to establish which territories each of them would get. As for the other defeated powers, the military clauses were bitter. The Army of the defeated powers was restricted to 50,000; the Navy to a few old ships; and no air force. The treaty included an inter-allied commission of control to supervise the execution of all the military clauses.

The Treaty of Sèvres, which formalized the partionist plans of the winners, could be read as a simple variation of a long-planned design to dismantle an enemy power (and then implemented with some important variations, like the inclusion of Greece). In fact, these policies were already in place ever since the signing of the Treaty of London, the St. Jeanne de Maurienne Agreement, the “Sikes-Picot,” and even the so-called Venizelos-Tittoni Agreement, a post-facto sub-agreement from the Peace Conference of Versailles.

The Treaty of Sèvres showed the worst face of the imperialist dreams of the winning powers, not only as in the above-mentioned military clauses, but with the establishment of Zones of Influence, which resulted in an imposition of a kind of multinational protectorate over the defeated country.

Under the treaty, within the territory retained by Turkey (excluding Armenia and Kurdistan), France received parts of Southeastern Anatolia, including Antep, Urfa and Mardin. Important parts of Cilicia including Adana, Diyarbakır and large portions of East-Central Anatolia up to Sivas and Tokat were declared a zone of French influence, garrisoned by troops of the newly established ‘Armée du Levant’ (on 7 October 1918), moving and expanding from their landing spot in Beirut (Octover 11). The first elements of this force came from the former “Armée d’Orient” with the ad hoc established “Division of Cilicia” (consisting of the 12th Infantry, the 17th Senegalese, 18th Algerian Regiments, and the Armenian Legion). A second unit, the “Division of Syria” (consisting of the 415th Infantry, the 3rd Zouaves, the 19th, 21st, and the 22nd Algerian Regiments) was rapidly set up, and tasked to expand French control in the assigned areas, while disarming Turkish and Arab troops in Syria and Lebanon.

Italy was given possession of the Dodecanese Islands (already under Italian occupation since the Italo-Turkish War of 1911–1912,) despite the Treaty of Ouchy, according to which Italy should have returned the islands to the Ottoman Empire. Large portions of Southern and West-Central Anatolia (the Mediterranean coast of Turkey and the inlands), including the port city of Antalya and Konya, were declared an Italian zone of influence. Antalya Province had been promised to Italy since the signing of the Treaty of London; and the Italian colonial authorities wished the zone to become an Italian colony under the name of “Lycia.”

Italian troops landed on 28 March 1919 in Antalya and then occupied Fethiye, Marmaris, Bodrum, Konya, Isparta and Aksehir. The Italian force was limited in terms of figures (13.000 troops with 3 regiments of infantry and support units) to control so expansive an area, which coincided with continuous infiltrations of Greek troops into Western Anatolia from the enclave of Smirna, about which there was complicit silence at the Spa Conference for the “Megala idea” of Venizelos. Independent of this contingent was an Italian infantry battalion in Constantinople, and another one was assigned in April 1919 to garrison Konya under British command. Great Britain did not establish any zone of influence; but within the terms of the ‘Sykes-Picot’ agreement, they took over almost all Mesopotamia, thus reinforcing their firm hand over oil resources of the region, and strengthening imperial control out to the Far East.

On 13 November 1918, the Allies landed in Constantinople with 2,616 British, 540 French, 470 Italian troops, supported by 50 ships (two days later, this grew to 167 ships).

On February 8, 1919, the French general Franchet d’ Espèrey, Commander-in-Chief of Allied Forces in the East, officially entered the city on a white horse, emulating Mehmed the Conqueror’s entrance in 1453 after the Fall of Constantinople, thus signifying that Ottoman sovereignty over the imperial city was over.

One year, after the Allies numbered 51,300 troops (27,419 British, 19,069 French, 3,992 Italians and 795 Greeks), garrisoning not only the city but also the neutralized zone of the Straits, largely assigned to units of the 122nd and 156th French Infantry Divisions and 28th British Division.

The Greek and Turkish police and gendarmerie forces operating in neutralized area were subordinate to Allied control; and the Constantinople area was garrisoned by British MPs (in Pera), The French Gendarmes (in Istanbul) and Italian Carabinieri (in Scutari) were supported by Turkish Jandarma personnel.

The Corps d’Occupation de Constantinople (COC) was formally set up on 6 November 1920, after more than one year of de facto occupation, when the drawdown of the Allied forces drastically reduced the level of their strength. Nominally multinational, it was nevertheless a harsh fight between the French and the British.

The COC was assisted by a military committee, formed by the commander of the national contingents and with three High Commissioners (in which, generally, the French and British were military and the Italian a diplomat). The job of the COC was focused on occupation duties and was affected by the bitter and growing polarization between the French and the British, while the Italian presence was little more than nominal.

The growing split among the Allies is widely attributed to the fact that the partition of Turkey had given to France too small a share. The Italians, too, were dismayed to the concession made by London to Athens, at Rome’s expense. This discontent gave rise to Franco-Italian support of the Turkish nationalist movement, both in Anatolia and in Constantinople, even if at the beginning, Paris supported to the end Greek expansionist dreams.

At the regional level, France had strong grievances against Britain, for it felt that British policies were contrary to prior agreements. For example, Britain did not want to share oil exploitations in the Mosul area, and, according to Paris, it stirred up Emir Faisal (the leader of the so-called “Arab revolt”) to attack French troops in Syria. In other words, France labelled the British approach as selfish and imperialist, although Paris applied the same policies in many other regions, like the Balkans, the Baltic Sea, Silesia, Poland, against not only their former enemies, like Germany, but also their present allies like Italy (and Britain).

The Allies had begun to split already in 1919, because of competing interests in Syria, Mesopotamia, Cilicia and the Aegean. TRhus, both France and Italy were eager to dismantle Turkey as a unitary state. But when their interests were undercut, they changed their plans. Also, Italy, because of prevalent domestic issues, confined its imperial aims in Turkey to just seeking out profitable economic concessions.

In the summer, the internal situation in Italy became untenable and Rome started the withdrawal of its troops from Anatolia and abandoned the dreams of territorial expansion in the Levant. The last troops left Anatolia in 1922. This happened mainly for two reasons. First, Italy obtained the Dodecanese islands, and second, there was a growing anti-Greek policy in Rome. But Italy kept small contingents in Constantinople and Adrianople, with a Carabinieri unit in Constantinopole until the general evacuation of foreign troops in October, 1923.

The functionality of the COC was seriously affected by the arrival, in the region, of 150.000 White Russian refugees (the army and civilians who fled after the defeat of General Wrangel in the Crimea), as well as the issue of the remnants of the Tsarist Black Sea Navy.

The other major, and final, crisis of the COC came after the defeat of Greek forces in Anatolia. The Greek-Turkish War saw a major shift in alliances among the Allies. At the beginning, France supported the demands of Greece, as Britain, in order to keep firm control over Turkey, kept out France. Then, Britain supported Greek expansion while. France, of course, along with Italy, moved to helping nationalist Turks.

The crisis was the trigger event of a failed and polarized political alliance, and the military contingents in the neutral zone operated in a disconntected way, reflecting the divergent stances of London, Paris and Rome vis-à-vis the development of the Greek-Turkish war. The final Allied withdrawal came under gloomy conditions, marked by ethno-religious violence between the Greeks and the Turks. When the withdrawal was formally signed into place, it ended the Allied entente of WWI.

The Russian Quagmire

Looking at the issue from an ethical or legal point of view, the Allied intervention in Russia was even worst than it was for the Ottoman Empire, where, at least, there existed a set of documents and treaties. For Russia, there were only ideological fears, old playbook and indolent behavior.

On 23 December 1917, the day after the beginning of the Brest Litovsk talks, delegates of France and Great Britain in Paris concluded a convention for the dismemberment of Russia and the establishment of zones of influence. London looked to the Baltic provinces and the Caucasus (especially its oil); France chose the Ukraine, from Belarus to Bessarabia and Donetz (for the iron, coal, iron and steel basins), as well as the Black Sea shores including Odessa and Crimea.

Soon after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 a three-year Civil War broke out in Russia. The initial phase of the war lasted for one year, and it was marked by rapidly shifting front lines and sporadic engagements by small units. At the beginning, the Bolsheviks generally expanded from the few urban areas in their hands to root out centres of opposition in the periphery of the vast country. This expansion began in the winter of 1917-1918, and it led to the formation of the anti-Bolshevik Volunteer Army, led by Generals Mikhail Alekseyev and Lavr Kornilov in the Don Cossack region, thus creating the southern front of the war.

Half a year later this was followed by the revolt of the Czechoslovak Legion (despite the name, in reality it was a force of the size of an army corps) on the mid-Volga and Siberia, which assisted the formation of two anti-Bolshevik governments, each with its own army – the Komuch in Samara and the Siberian Government in Omsk.

The Red Army of Lenin’s Bolshevik government was rapidly formed to replace the irregular Red Guard partisan units only at the end of this phase, in the fall of 1918.

The second and decisive stage of the Civil War lasted from March to December 1919. First, the White armies of Admiral Alexander Kolchak in Siberia and General Denikin in Southern Russia advanced resolutely toward Moscow (the last one appeared to be the most decisive push against the Reds). In the Caucasus and Crimea operated General Wrangel (probably the best of the White generals). In the North-West General Yudenich tried to attack Petrograd.

As in many other civil wars, foreign powers intervened in the conflict. Britain played a leading role in this intervention and had a significant effect on the course of the war. Without this foreign intervention on the White side, the superiority of numbers in manpower and weaponry of the Bolsheviks would have quickly overwhelmed their opponents.

British Intervention In Southern Russia, 1918-1920

Despite massive support, the entire British action remained uncertain and split between an ideological battle against Bolshevism and the strategic imperative to protect India and investments in the oil industry in the Middle East (Persia and Mesopotamia). Consequently, the action of Great Britain, while strong in Southern Russia, and massive (two divisions) in the Caucasus and Central Asia – in Northern Russia and Eastern Russia (Siberia) it a lot less intense.

Further, the controversial demobilization scheme, the requirement to keep the public unaware of the extent of the military efforts, and the risk of bolshevism infecting the troops contributed to the incertitude of the British (and French) actions.

From November 1918 the Allies succeeded in supplying regular provisions to the White Armies mainly through the Black Sea port of Novorossiysk. The British military mission arrived in South Russia in late 1918, and provided General Denikin’s White army with an enormous amount of matériel. This included full British army kit for half a million men, 1,200 field guns with almost two million rounds of ammunition, 6,100 machine guns, 200,000 rifles with 500 million rounds of ammunition, 629 lorries and motorcars, 279 motorcycles, 74 tanks, six armoured cars, 200 aircraft, 12 500-bed hospitals, 25 field hospitals and a vast amount of signal and engineer equipment. All this was sufficient for an army of 250,000 men and it was much more than Denikin was ever able to use, as the combat strength of his army never exceeded 150,000 men. Ammunitions destined for South Russia also included 25,000 poison gas shells. Churchill had described mustard gas as “ideal weapon against our beastly enemy.” But British personnel were instructed to use it only if the Bolsheviks started gas warfare first.

The British mission also organized the training and equipping of White Russian troops with British weapons. This made the material aid much more effective. Even in small numbers, many of the British instructors, following a personal and ideological commitment, took part in fighting the Bolsheviks, despite the orders of their government.

In real terms, financial and material support from Great Britain pushed Denikin’s army in a far more favourable position than the Bolsheviks in 1919, and very close to being the key element of the victory of the Whites against the Bolsheviks. But the White army of Denikin suffered, like the Tsarist army, of which it was but an extention. This led to serious problems. White officers were unimaginative; their mindset remained obsolete; and they were incapable of organizing the logistics of their army. There were also fundamental defects in the morale of the White troops. These limits affected all the other White armies operating against the Bolsheviks, without mentioning the bitter rivalries among the White generals themselves.

In addition to all the political mistakes of Denikin’s movement and a general inability to adjust to the complex situation in Revolutionary Russia, the Whites suffered a clear military defeat. In South Russia, the Whites were defeated not because of the lack of British aid, but rather despite it; and their defeat was decisive for the victory of the Reds elsewhere.

The British presence in Southern Russia, as mentioned, was limited to few hundred specialists and trainers and non-combat troops (72 servicemen -18 Royal Navy, 41 British Army, 13 Royal Air Force personnel – were killed in South Russia in 1918-1920).

Further, they were scattered over the immense area of Southern Russia, where several White units operated, of which the Denikin one was the larger, but also Wrangler’s that extended to the Caucasus.

The missed arrival of a massive British combat force led to the first rift between the Whites and London. British combat troops were deployed, and in a limited number, only in the South Caucasus to secure the oilfields there (the Baku area); and this situation increased the suspicions of White Russians over the real, future aims of British aid.

The real strategic reason for the massive support of Denikin, who operated mainly in the “zone of influence” assigned to the French, was because of the failure of previous, but also because of the defeat of Admiral Kolchiak’s offensive in Siberia. But lagely these troops came to protect the interests of London over the oil resources in Baku and surrounding region.

After Denikin’s army was decisively defeated at Orel in October 1919 (some 400 km south of Moscow), the White forces in southern Russia were in constant retreat, reaching the Crimea in March 1920. In July 1920, the White forces left Crimea for Constantinople. This ended the British Mission in Southern Russia.

The fate of the British military mission in South Russia followed the fate of the Whites, with constant relocation of the training teams under growing pressure from the Reds. First this progressive impairment, and later the demise of Denikin’s and Wrangel armies impacted the broader plans of London to set up “friendly” states in the South Caucasus – the real strategic objectives of British military expedition in the former allied territory.

At the end of August 1919, the British withdrew from Baku (the small British naval presence was also withdrawn from the Caspian Sea), leaving only 3 battalions at Batum. After a British garrison at Enzeli (on the Persian Caspian coast) was taken prisoner by Bolshevik forces on 19 May 1920, Lloyd George finally insisted on a withdrawal from Batum early in June 1920, thus disbanding the 27th Division (The British Salonika Army was split within Macedonia [22nd Division, disbanded in 1919], the Danube [26th Division, disbanded on May 1919], Turkey (28th Division, disbanded on December 1923], and the Caucasus [27th Division, disbanded in 1920]). Financial concerns forced a British withdrawal from Persia in the spring of 1921.

The French Intervention In Southern Russia

The French intervention in Southern Russia was initiated in February 1918, with 50 million rubles in gold to the Ukrainian Rada. But the first official sign of French preparation for direct military intervention in Southern Russia came on October 7, 1918, when Clemenceau designated General Henri Berthelot to head a military mission with responsibility for operations in Romania and the Ukraine. While an important task of this expedition was to assure the retreat of German and Austro-Hungarian forces from the Ukraine and Romania, Clemenceau’s instructions stressed the need to set up an economic encirclement of the Bolsheviks and help along the fall of the new government in Russia.

However, French intervention in support of the Whites (also in this case for ideological reasons to hinder the path of the Reds) was much shorter and much more confused than by the British – and was shut down only after a few months.

The French expedition had come to Southern Russia under three assumptions, which emerged to be totally baseless: A) that the Whites representing a majority of the people; B) that the Russian people welcomed Allied intervention against Bolshevik; and C) that the bulk of the fight against the Reds would be on the White forces, requiring only moral and technical assistance from the French forces.

In fact, the Ukrainians preferred the Bolsheviks to the Whites; the local population resented Allied intervention; and the Whites had limited capabilities. Disillusionment with intervention increased as officers and soldiers alike realized that the entire population of Southern Russia looked upon their presence with undisguised hostility.

As one officer in Sebastopol declared, Bolshevik propaganda had little effect upon the troops, but the hostile attitude of the local population had a profound impact on troops already exahusted by the tough Salonika campaign.

At initial meetings with Russian Whites, Berthelot promised up to 12 Allied divisions as expeditionary forces in Southern Russia, when in reality only three divisions were in theory available. However, six weeks after first landing in Odessa, the Allied force did not exceed 3.000 ground troops (three infantry regiments [176th, 58th French, 1st Regiment de marche africain, elements from the 10th Algerian Regiment, the 21st Chasseurs Aborigines, the 129th Senegalese Batallion, the Batallion Chasseurs d’Indochine, 4th Chasseurs á cheval d’Afrique]; other support elements [the 19th and 242nd Colonial Artillery, 7th Engineer Regiment]; landing parties of the French naval squadron, augmented by a sizeable Greek contingent, and smaller units of Polish, Romanian and Czech troops). But they did seize Nikolaev, Kherson and Tiraspol, so that Allied forces controlled an arc of territory in the Western Ukraine, along the northern shore of the Black Sea, between the Dniester and Dniepr rivers.

The absence of reinforcements further increased the French command’s skepticism about intervention. But the major problems were the open and tough hostility of the local populations, as a result of Bolshevik propaganda, and the splits among the anti-Reds, the split among the White generals (who wanted to re-establish Tsarist Russia), and local Ukrainian independence movements (split among different factions, running from ultraconservative to anarchist groups).

As among the British, the French also had several dozen advisors and staff personnel, who similar to their British counterparts expressed criticism and doubts about the performance of White leadership and troops and even White military capabilities.

By March 1919, pressure frm the Bolsheviks forced the Whites (and consequently the French and Greeks) to evacuate initially Kherson, and then Nikolaev, putting serious doubt on the validity of the entire operation in the Black Sea. Red attacks over Odessa only grew greater.

The anti-Red coalition was marked more and more by bitter rivalries, which quickly undermined the White armies; Greek forces were more concerned about the safety of the Greek national community there and the beginning of the operation in Asia Minor against the Turks. This weakend further the French-led effort in Southern Russia.

The situation became so untenable that General D’Esperey went urgently to Odessa from Constantinople, realizing that were no other option than to withdraw from there (the evacuation came finally on 6 April). But he did this without consulting the Whites (Denikin was informed ex post facto by Franchet d”Esperey).

The Odessa evacuation left the Crimea as the only remaining area of direct French military intervention. Clemenceau had urged to hold the Crimea as a bastion for future actions in Southern Russia, again creating the impression of a firm French commitment. Yet, from the outset, the French presence in the Crimea had been marked by the same difficulties that plagued the intervention in the Ukraine – but this time, there was the brave White General Wrangel, who could not hold, despite considerable efforts to re-establish good relations with the local populations (that fully supported the Reds). This led him to a desperate evacuation to Constantinople at the end of April.

The withdrawal from Sebastopol was marked by a serious disciplinary situation, especially on board French naval ships operating in the Black Sea. This was the persistent and growing mutinous attitude among the French forces operating in the area.

The Black Sea mutinies have acquired legendary dimension among Marxist historians, largely as a result of André Marty’s somewhat exaggerated claims, and as a result of the “martyrdom” of those sailors condemned by military tribunals. There is no doubt, however, that the mutinies were serious and extensive.

The first uprisings took place among ground troops. On the 4th of February, the 58th Infantry Regiment refused to fight at Tiraspol on the far bank of the Dniester.

On March 8th, two companies of the 176th Infantry Regiment rejected an order to attack at Kherson. April 5 saw the same refusal among elements of the 19th Colonial Artillery Regiment in Odessa, where sappers of the 7th Engineer Regiment fraternized with, and left equipment for, the Bolsheviks. Then, from 10 to 30 April, major mutinies of sailors take place. In Romania, at Galatz, the chief mechanic André Marty planned to seize the torpedo FNS Protet, lock up the officers and rally the Bolsheviks to Sevastopol. The plot was discovered, he was arrested on April 16, and sentenced to twenty years of hard labor.

On April 17, on the cruiser FNS France, protests broke out; four sailors were put in the brig. But two days later, the revolting crew freed them, elected delegates, and demanded the return to Toulon.

On the 20th, the red flag was hoisted on FNS France, FNS Jean-Bart, FNS Justice, along with the singing of the L’Internationale. In the afternoon, sailors who had demonstrated in Sevastopol with the population returned fire of Greek soldiers. Calm returned in the days following; and the delegates, who initially obeyed, saw their role decrease. But FNS Jean-Bart as well as FNS France returned to Toulon and Bizerte.

Another mutiny took place on the 25th on-board FNS Waldeck-Rousseau stationed at Odessa. A committee of sailors decided to revolt, demanded the freedom of Marty and the return to France. In the following days, control was exerted over buildings in Odessa, as well as over all ships in the Black Sea. But the excitement continues into May and June, in the naval bases of Toulon, Brest, Bizerte, Greece (and on board FNS Guichen, led by Charles Tillon) and even in Vladivostok.

As mentioned, the Sebastopol episode marked a climax in a series of mutinies, and rather extensive indiscipline among troops throughout the Ukrainian and Crimean interventions; and the French command was well aware of the low morale and war-weariness among the ranks. Whether this attitude reflected a widespread sympathy for Bolshevism is less clear. The majority of the French soldiers had no desire to fight in Russia and demanded repatriation.

However, some fully supported the Bolsheviks; and the demonstration in Sebastopol revealed a degree of political support for the Russian Revolution that was of considerable significance. But it is not clear that a majority of the soldiers and sailors were prepared to embrace the revolution at this point. Above all, it is an exaggeration to claim that the mutiny in Sebastopol was because of an untenable military situation. Instead, it was because of several factors, already discussed, without mentioning the lack of political support of France from other Allies despite the fury of Clemenceau.

The French military intervention in the Ukraine was a sobering lesson in the perils of intervening in another nation’s civil wars.

Conclusion

The action of Allied powers, in the two cases discussed, revealed the persistence of an imperialistic stance of some countries, despite their exhaustion and their formal adherence to the 14 Points Declaration of President Woodrow Wilson.

This contradiction is the result of a wild era which existed well before the breakout of WWI, behind the façade of economic and social developments at the end of the 19th and the beginning of 20th centuries.

Appendix

Turkish Post-War And Straits Occupations 1918-1923

26.04.1916: Agreement of St.-Jean-de-Maurienne between France, Italy and Great Britain.

16.05.1916: Sykes-Picot Agreement between France and Great Britain.

30.10.1918: Armistice of Mudros: Turkey to cease hostilities, demobilize, open the Bosporus Straits, and repatriate POWs. The Armistice found the British occupying most non-Turkish territory of the Ottoman Empire (Palestine, Mesopotamia, Kurdistan), and Arab insurgents in control of the Hejaz and parts of Syria.

12.11.1918: French troops land in Constantinople.

13.11.1918: British troops land in Constantinople.

08.12.1918: Allied occupation of the Bosporus, the Dardanelles, the eastern coast of the Sea of Marmara, islands of Imros, Lemnos, Samothrace, Tenedos, and 15 km deep into the eastern shores; the zone of the Straits is demilitarized (by Greek and Turkish forces) but garrisoned by Allied forces.

18.01.1919: Peace Conference opens in Versailles.

Jan. 1919: Turkish garrison in Medina surrenders to the forces of the Arab revolt.

03.02.1919: In Paris, Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos demands the entire of East Thrace and the Aegean shores of Anatolia, including Izmir to be annexed to Greece.

07.02.1919: Italian troops land in Galata (Constantinople).

08.02.1919: French General Franchet d’Esperey, commander of the Allied Army (later the Constantinople Occupation Corps), enters in Constantinople mounted on a white horse.

04.03.1919: Damat Ferit Pasha, brother-in-law of the Sultan, appointed as the new Grand Vizir (Prime Minister).

29.03.1919: Italian troops land in Antalya.

08.04.1919: British Foreign Minister, Lord Balfour, proposes Istanbul become a neutral zone under the administration of the League of Nations (also French Prime Minister Aristide Briand proposes the creation of a “free city,” a sort of protectorate under the League. The city of Constantinople would be a first free city in 1920. As such, Constantinople would have its own municipal government, but which would be devoid of any of those functions of government exercised by a sovereign state, such as, defense and foreign relations).

30.04.1919: Sultan Vahidettin sends Mustafa Kemal to Anatolia as Inspector-General.

06.05.1919: Allied powers agree to allow Greeks to occupy Smyrna.

15.05.1919: Smyrna occupied by the Greek army. Journalist Hasan Tahsin shoots a Greek flag bearer, firing the first bullet of the Turkish resistance.

16.05.1919: Mustafa Kemal leaves Constantinople.

19.05.1919: Mustafa Kemal arrives in Samsun. Turkish War of Independence begins.

24.05.1919: Demonstration at Sultanahmet in Istanbul against the occupation of Smyna.

22.06.1919: Mustafa Kemal issues the Amasya Declaration stating that the independence of the nation will be saved once more by the determination and decisiveness of the people.

28.06.1919: Treaty of Versailles signed by Germany.

23.07/07.08.1919: Erzurum Congress. It is decided that there will a struggle with the enemy of the people in the Eastern provinces which are an inseparable part of the homeland.

10.10.1919: Allied forces officially take military control of Western Thrace.

22.10.1919: Inter Allied administration of Western Thrace begins with French General Charpy appointed Governor.

04-11.09. 1919: Sivas Congress. A mutual decision about the “homeland being an indivisible whole” is reached. All the local resistance organizations in the country are united and a “Committee of Representatives” is formed.

01.11.1919: Grand Vizir Damat Ferit Paşa resigns.

27.12.1919: Mustafa Kemal arrives in Ankara.

12.01.1920: Opening session of the last Ottoman Parliament.

10.03.1920: Allied Military Administration of Constantinople and Straits Zone formally established.

16.03.1920: Constantinople officially occupied by Allied forces.

20.03.1920: Italian troops withdraw from Konia.

05.04.1920: Damat Ferit Paşa reappointed as Grand Vizir.

11.04.1920: Ottoman Parliament dissolved by Sultan Vahidettin.

19-26.04.1920: The San Remo Conference of the Allied Supreme Council determines the allocation of the League of Nations mandates for administration of the former Ottoman ruled lands of the Middle East by the victorious powers.

23.04.1920: The Turkish Grand National Assembly opens in Ankara.

20.05.1920: Greece annexes Western Thrace.

22.06.1920: Greek offensive in Anatolia begins.

08.07.1920: Greek forces occupy Bursa.

12.07.1920: Greece moves into Eastern Thrace, setting up Adrianople as headquarters.

15.07.1920: Greek forces occupy Edirne and the entire East Thrace.

10.08.1920: Ottoman government signs the Treaty of Sèvres with the Allied nations. Hejaz, Armenia and Assyria are to become independent. Mesopotamia and Palestine are assigned under mandate to the tutelage of the UK, Lebanon and an enlarged Syria to that of France. The Dodecanese and Rhodes with portions of southern Anatolia are to pass to Italy, while Thrace and Western Anatolia, including Smyrna will become part of Greece. The Bosphorus, Dardanelles and Sea of Marmara are to be demilitarized and internationalized, and the Ottoman army is to be restricted to a strength of 50,000 men. The treaty is rejected by the Turkish republican movement in Ankara.

06.11.1920: The Corps d’Occupation de Constantinople (COC) formally is set up, led by French General Franchet d’Esperey (frmr. CinC of Eastern Allied Forces).

03.12.1920: Ankara signs the Gümrü Peace Agreement with the Republic of Armenia.

09-11.01.1921: First Battle of İnönü. Greek advance inside Anatolia halted.

20.01.1921: The first Turkish Constitution is ratified by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey.

21.02/12.03.1921: London Conference. Representatives of both Istanbul and Ankara governments are invited to the conference which aims to revise the Treaty of Sèvres. It does not achieve any results.

16.03.1921: Bolshevik Russia recognizes the new Turkish State.

27-20.03.1921: Second Battle of İnönü. Greek offensive fails.

25.05.1921: Italians troops withdraw from Marmaris.

21.06.1921: Italians withdraw from the Antalya region.

05.07.1921: The city of Antalya is returned to the Turkish government by Italian military authorities.

10.07.1921: Greek forces launch a new offensive;

18.07.1921: The British General Harrington is made CinC of COC, replacing the French General Charpy; the (British) Black Sea Army is re-named as British COC of Constantinople; the 28th British division is dissolved.

19.07.1921: Turkish forces retreat towards Ankara.

10.08.1921: The Allied Supreme Council declares neutrality with respect to the Turkish-Greek conflict;

23.08/13.09.1921: Battle of Sakarya. Greek forces retreat after a failed offensive.

20.10.1921: Peace agreement signed between Turkey and France.

23.10.1921: Treaty of Kars between Turkey and the USSR. Turkey cedes the city of Batumi to the USSR in return for sovereignty over the cities of Kars and Ardaha.

11.01.1922: Mustapha Kemal proclaims the abolition of the Ottoman sultanate and the establishment of the Turkish Republic; Sultan Mohammed VI flees Constantinople on board a British warship.

31.05.1922: Last Italian troops leave the area of Antalya.

05-19.07.1922: USMC troops from the USS Arizona land to guard the US Consulate in Constantinople;

26-30.08.1922: Battle of Dumlupınar. Decisive Turkish victory against the Greek forces.

09.09.1922: Turkish troops take Smyrna; massive killing of Greek and Armenian populations.

15.09.1922: British government appeals to the Dominions for military support in the Turkish crisis, but the Dominions decline; France and Italy also refuse help.

15.09.1922: Greek occupation ends.

16.09.1922: A British force lands at Canakkale, Turkey.

03-11.10.1922: Convention of Mudania; the Allies agree to return Eastern Thrace and Adrianople to Turkey, and Turkey accepts the neutralization of the Straits under international control.

11.10.1922: Armistice of Mudanya signed between Turkey, Italy, France and Britain. Greece accedes to the armistice three days later. East Thrace as far as the Maritsa River and Edirne are handed over by Greece to Turkey. Turkish sovereignty over Constantinople and the Dardanelles is recognized.

20.10.1922: Peace Conference opens in Lausanne.

01.11.1922: The Sultanate is abolished.

17.11.1922: Sultan Vahidettin leaves Istanbul on board the British warship Malaya.

04.02.1923: Talks in Lausanne interrupted because of Turkish protest about the contents of the Lausanne conference.

23.04.1923: Talks in Lausanne resume.

24.04.1923: Treaty of Lausanne signed between Turkey, Greece and other countries that fought WWI and the Turkish Independence War. Turkey recovers full sovereign rights over its territory.

10.06.1923: Turkey takes possession of Constantinople.

24.07.1923: Treaty of Lausanne formally replaces Treaty of Sèvres.

06.10.1923: Occupation forces begin withdrawal from Constantinople.

13.10.1923: Ankara declared as the capital of the new Turkish State.

06.10.1923: Units from the Turkish 3rd Corps, commanded by Şükrü Naili Pasha enter Constantinople.

23.10.1923: Last allies (British contingent) troops evacuate Constantinople.

29.10.1923: The Republic of Turkey is proclaimed.

Enrico Magnani, PhD is a UN officer who specializes in military history, politico-military affairs, peacekeeping and stability operations. (The opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations).

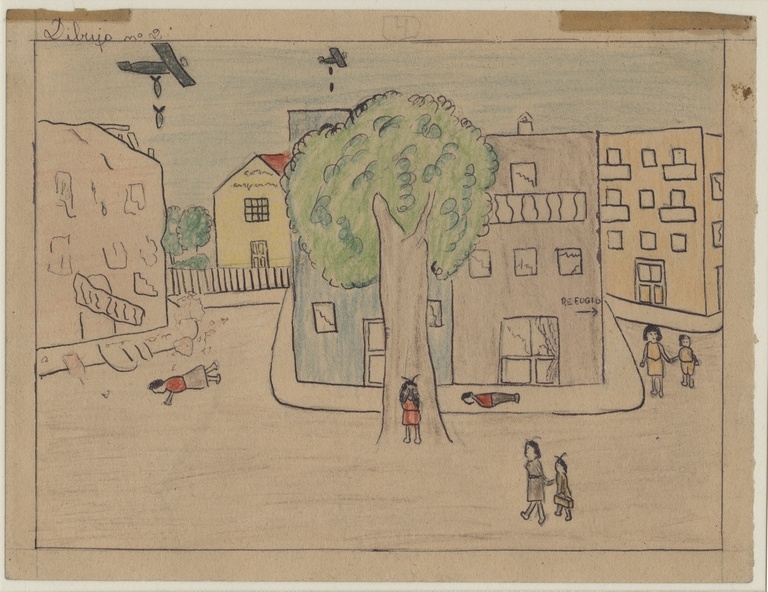

The image shows, “The Flight of the Bourgeoisie from Novorossiysk in 1920,” by Ivan Vladimirov; painted in 1920.