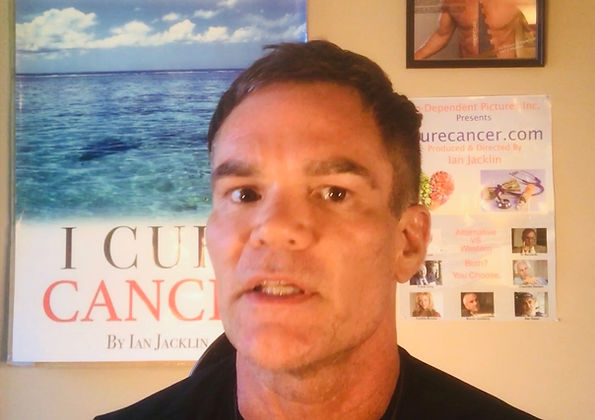

Ian Jacklin is documentary filmmaker, concert promoter, actor, and kickboxing champion. He has produced three films and holds one world kickboxing title. He is in conversation with Grégoire Canlorbe.

Grégoire Canlorbe (GC): You are ranked number two in the world by the World Kickboxing Association. Please tell us about this incredible accomplishment.

Ian Jacklin (IJ): Like many young men, I saw a Bruce Lee movie and was hooked. Especially when on the first day of grade 9 high school I had to watch a buddy of mine get beat up while being held back. I went home that afternoon and told my mom to put me in Karate at 14 years of age; and the rest is pretty much history.

Ralph Chinnick was my master at Professional Self Defense Studios in London, Ontario, Canada. His early instruction was to learn the technique. To just keep coming to every class and learn the technique. Which I did and did well.

By the time I was a yellow belt I was kicking like black belts. By the time I was a green belt I was beating black belts in sparring. And the great thing about Kenpo karate under the Ed Parker system was we actually kickboxed. No point sparring. Real fighting. And I heard then that Bruce Lee said that you learn to fight by fighting.

So it was a natural progression to go to other dojos and spar their best guys, which I did in Kitchener Ontario at Sifu Ron Day’s Kung Fu Academy, where was the future PKA lightweight champion of the world, Leo Loucks. He became my idol; and I learned from him. on his rise to the top, when he beat Cliff Thompson.

Our trainer Jimmy Fields was the best in proactive, positive mental instruction, while in the deepest and darkest moments of battles in that square circle.

I had other trainers that would try to scare you into being better. But that never worked for me. Militant instruction may work for some, but it didn’t work for me. I needed love and light, and Jimmy gave me that. I truly believe that if he and Ron Day were to be my handlers for my career I would have not only fought for the world title but would have won it and kept if for a long time. But alas… it wasn’t meant to go that way. Apparently, the universe had bigger plans for me.

I won the Canadian ISKA title by beating Conrad Pla in Montreal, when I was 18. I fought Mark Mongo Longo for the North American title in Gleasons Gym Brooklyn, which went to a draw. Many including myself thought I won that fight but it was in the US and I was Canadian, so… it was what it was.

Not long after that Lennox Lewis won the Gold in the 1988 Olympics, and he was from Kitchener Ontario Canada; so, it was only fitting for his pro debut to be in Toronto. They trained in our Kitchener Kicks/Ron Days Kung Fu Academy for that fight, so they got to see me in action. They saw a white boy that could fight and took me back to England with them.

I actually started in boxing, before karate, as a kid hanging, out at the Boys and Girls Club, London, Ontario, Canada. And although my kicks were my best weapon, my hands weren’t too shabby either.

But being in the Lennox Lewis pro boxing stable really improved my hands, and I had a lot of fun living in London, England for a while. John Davenport and Harold “The Shadow” Knight were my trainers.

After about 4 months, I decided I didn’t like where I was. I mean Lennox and the guys were cool, but London just rained every day and it was really depressing. My high school sweetheart was back in Canada and I really missed her and my family, so I eventually quit and headed home.

The main thing was, I couldn’t believe how many shots to the head I was taking in boxing compared to kickboxing. I mean my legs were wicked, so most guys never got the chance to punch me in the head; but in boxing that’s all you do. I knew if I stayed in that sport I’d be punch drunk and ugly within a few years. Besides, I had been watching Bay Watch on one of the 4 channels England had on their TV and had been California-dreaming.

Back in Canada, I worked the summer, continuing my electrical apprenticeship with Gordon Electric in my hometown of London Ontario, Canada. I had no plans. I just knew that I wasn’t done fighting and still had my dream of fighting for the world title as Leo did.

And then it happened. With 3 days’ notice, I broke up with my girlfriend, quit my job and packed up my motorcycle with a tent and sleeping bag, and headed to Hollywood, California.

Although heartbroken due to making that decision to follow my dreams, which didn’t accommodate a girlfriend whom I dearly did love… I also felt more alive than I ever had been, knowing I was going to take a shot at not only pursuing my dream to fight for the title, but maybe even get into Hollywood as an actor. After all Jean Claude Van Damme was there making all his martial art movies. So, I figured it was worth a shot.

It was such a dilemma leaving your girlfriend, family, friends, and career on a whim for the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. I sped through the mountains in various areas on the way to Cali with abandon. So much so that I even crashed once and almost fell off a cliff, if it weren’t for that 3-foot-high cement barrier. It was like I wanted to die for what I left, but wanted to live for what lay ahead… hard for me to put into words. But apparently, somebody up there likes me. And after picking the rocks out of my flesh and a quick stop at a local motorcycle shop, I was back on the road. It was the summer of 1990. It wasn’t my time to die yet. Hollywood here I come.

I stayed in Whittier, California with Les Sickles, the brother of one of my home boxing trainers. Jack Sickles was my mentor in Canada and his brother became that in California. He was 85 when I first met him. We became fast friends and I truly had some of the best years of my life with him as a newbie in Southern Cal. He was now a widower and had been a pro boxer when he was young, so just loved tagging along with me to the gyms.

I fought and won the North American WKA championship and eventually went to fight Javier Mendez for the world ISKA Cruiser Weight title fight in 1993. I fought him a few years earlier and beat him. Then he beat me this night and took the title. But the point is, my dream was to fight for the world title and I did that! Also, I wanted to star in a Hollywood movie, which I quickly achieved, thanks to befriending legend, Don “The Dragon” Wilson. He became my sparring partner which elevated my fighting skills and put me in a bunch of his movies like Ring of Fire II where I played the lead bad guy.

My film career included Kickboxer 3. The bad guys of the Kickboxer movies. I remember the night my agent told me I got the role. It was about a year to the date of me arriving in Tinsel Town. I was working as the VIP bouncer at the Roxbury which many know was the Studio 54 of the day. I babysat more drunk actors and rock stars than I could count in those days.

And sure enough, Jean Claude Van Damme was in the Roxbury that night. I asked Elie Samaha, one of the owners, to introduce me to him, which he did. I thanked him for doing Kickboxer the movie, so I was able to get the lead bad guy role in Kickboxer 3. He looked at me and squeezed my cheeks and said with a face like that you should be the star! I laughed and said maybe someday, man! Maybe someday! And sure enough, that did happen. I ended up being the good guy in Expert Weapon and Death Match down the line.

Many of you have heard that to make it in Hollywood you have to sell your soul. I’m not 100 percent on that, but I was offered a multi-picture movie deal if I would have slept with a gay producer. I said no thank you and left Hollywood. I had put 10 years into that place and was tired of the rat-race—and if that was the only way I was going to make it, I knew it was time to leave.

Long story longer… I went to NYC and became a filmmaker.

GC: Which leads me in to my next question. How did you move from being a kickboxing-champion to championing holistic medicine and alkaline?

IJ: So, Hollywood wasn’t a total waste of time. While doing a play I met an actress, J. Cynthia Brooks, who like myself had been on Days Of Our Lives among many other shows and movies over the years. We actually had met at the Roxbury years earlier, and now working together on a play, called Spoiled Women, I found out she had just cured herself of terminal cervical cancer. I overheard this at a rehearsal one day, and it lit a fire under me like few other things have.

I said, “What?! You can’t cure cancer. What do you mean, you cured yourself of cancer?”

And as I’ve said before the rest is history. Turns out instead of doing the usual chemo, radiation and surgery she followed a friends advice and did holistic medicine and dropped meat, dairy, sugar. Used a “Rife” machine and meditated a lot. Cured her terminal cervical cancer (of which she was given one year to live, if she did the western medical treatments) in 8 months.

I had thought cancer ran in my adopted mom’s family, so worried for her. I dove deeper. It was when the internet first started, so I researched others that claimed they too cured their cancers with holistic methods; and then I would call them too, so I could validate via their voice if they were real or not. And they were.

So, I decided to make a documentary about it, and called it by the name of the website I also started, ICureCancer.com.

Thanks to doing that I learned a lot about health and wellness, and have been a cancer coach ever since. The key is to drop the acidic lifestyle from what you eat, drink, think, breath, and these days the wifi radiation you sit in. You can book a health coaching session with me at IanJacklin.com, if interested.

GC: I must say that your fight with Sasha Mitchell at the end of Kickboxer 3: The Art of War easily ranks among the dramatic highpoints in the Kickboxer saga.

IJ: Wow! Thank you for that compliment. My favorite bad guy of the series (me included) was Tong Po! He was the best actor. The original kickboxer film with Van Damme was shot so well, too. Edited well. But for a sequel I thought KB3 was done quite well too. And we had Shuki Ron as the choreographer, who let me be the pro kickboxer I was, to make it, what I thought, one of the most realistic fight-scenes in the series, for sure.

I mean, I was actually still fighting pro kickboxing in the ring in between movies, and I don’t know how to movie fight. Just fight. And luckily by the time Sasha Mitchell and I worked together, he had been training as a kickboxer for a few years, so he was much more believable for Kickboxer III: The Art Of War.

GC: How did it feel to play a good guy (and leading character) in Death Match?

IJ: I loved being the good guy! I mean I’ve always said in real life I’m not an actor, I’m a super hero. But they don’t pay super heroes, so I have to moonlight as an actor.

GC: Do you believe a great action-movie could be made about what you call the “scamdemic?” Would you be ready to act in such movie?

IJ: Lol. Yes, that would be great! It would be me and a bunch of human beings fighting the reptiles like in They Live! I have the power to decipher who is one and who isn’t and boom we take out the ones that are. Finally, planet earth will be run by human beings, not Draconians!

GC: Thank you for your time. Anything else that you would like to add?

IJ: I’d just like to say for everyone that wants to be a hero in real life, start local. Go to your board meetings and vote out the leftist demoncrats. Watch the movie, 2000 Mules to see the truth. Trump won. End of story! Not saying he’s perfect—but come on… Biden? What a joke the bankers played on us!

Get to know your cops and sheriffs, and band together. We cannot let the Illuminati scum run us anymore. The whole scamdemic thing must never happen again. They just rebranded the flu and turned on 5G. That’s it!

I wrote my 3rd book, ConVid 1984: Antidote, which explains the hows and whys humanity got raped and pillaged by the bankers. I explain how to detox, for anyone that got suckered in to the shots. Or just wants to be healthy. You must get Alkaline, as explained in both my earlier books I Cure Cancer and Alkaline: Dr. Robert O. Young’s pH Diet & Mindset. Take good supplements: Whole food supplements. Grow your own organic food year-round.

Featured image: “Asian martial arts beauty,” by Phung Wang of Vietnam; painted in 2018.