Let us talk of many things, as the Walrus said, but primarily, of Neoreaction. What follows is the start of what I hope to make an extended exploration of this line of thought, for which I have much sympathy. I embark on this project for four reasons.

First, to amuse myself. Second, in order to make my own thinking coherent, for confusion already stalks the land, and why add to it? Third, in the hope that what I say may bring value to others, since a man should not bury his single talent. And fourth, so that in some small way, in a manner yet to be revealed, this combination of analysis of others and thoughts of mine will help to either forge the future, or smash and remake the present.

The projected form of this exploration is an initial series of book reviews, drawn with an eye to weaving them together into a coherent whole that supersedes the reviews themselves. It is important to note that this is an investigation, with an uncertain end. But I expect to come to a definite conclusion, with both a coherent summary and recommendations for a cogent, directed set of political actions. The focus will therefore be practical politics, not pure abstractions, although of necessity there will be much political philosophy, which I will keep as grounded as I can.

To kick off the concretization of things, I will drop the prefix “neo,” for it adds nothing. The term “reactionary” denotes a range of current political philosophies (its only other meaning today is as a generic and content-free term of abuse), and I will save a lot of ink by simply eliminating the prefix.

Of course, even at this early point, numerous overarching problems present themselves that would not present themselves in evaluating more mundane political issues, such as tax policy.

The first is the need to weed out insanity. Fringe political movements, which reaction is for now, tend to attract a dubious cast of characters, and the Internet exacerbates their reach and perceived numbers.

Moreover, insanity divides into two branches – a mere denial of, or departure from, reality, relatively easy to recognize; and a failure to realize that any idea is only useful insofar as it may find fertile ground on which to fall.

Politics is the art of the possible, and hope is not a plan.

A second problem is the undeniable racism (in its actual, not imaginary or accusatory, sense) of a non-trivial percentage of reactionaries. It is not enough for reactionaries to glibly dismiss this problem, just as it is not enough for progressives to coolly dismiss (though they usually rather celebrate) their close association, and long-lasting symbiotic relationship, with the mirror image of racists – their own violent and nasty extremists, such as Communists, or the so-called Antifa.

This problem should not be permitted to dominate or cloud the discussion, or result in any sort of pre-emptive apology or obeisance, as progressives would love to require, but it deserves discussion.

A third challenge, related to but distinct from the second, is that much reaction is profoundly opposed to Christianity, openly or covertly, and therefore its success would pose a risk of fracture to the bedrock of Western civilization.

In the inspired words of Ross Douthat, if you don’t like the Christian right, you really won’t like the post-Christian right.

Thus, in some ways my exploration lies at a tangent to Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option, not in that it hopes to expand or clarify his vision, which is complete enough in itself, but to outline political actions that can serve as armed outrider, an implementation of my own Mendoza Option (from the character in the film, “The Mission”), without wholly degenerating into an amoral reboot of society.

A fourth problem, related to the third, is that it is easy to forget that political theory is only helpful so long as, and inasmuch as, it conforms to the underlying reality of things, rather than being a pleasing abstraction, a program that attempts to change the unchangeable.

A theory fashioned in isolation but designed for imposition in and upon the real world is, in a very real sense, the Devil’s craft. I hope to remain sensitive to and directly address each of these problems, as well as others that are sure to arise.

So off we go!

This is supposed to start as a review of Mark Lilla’s The Shipwrecked Mind, a loose collection of essays about reaction, published as a group in early 2016, before  the rise of Trump. Certainly, Trump himself is not a reactionary. However, just as certainly, he has been advised by men who are very definitely some brand of reactionary, most notably Steve Bannon and Michael Anton, the latter still serving in the White House.

the rise of Trump. Certainly, Trump himself is not a reactionary. However, just as certainly, he has been advised by men who are very definitely some brand of reactionary, most notably Steve Bannon and Michael Anton, the latter still serving in the White House.

Until Trump, what little attention was directed at reaction revolved mostly around obscure dead people with ties to twentieth century radical right movements, such as Julius Evola, or around the largely incoherent ramblings of a subset of techno-libertarians, whom I suspect are mostly the kind of people away from whom you edge at cocktail parties.

Lilla was among the first to perceive that there was more to the movement, but post-Trump, reactionary thought began receiving substantial attention. Most of this was a wave of stupidity emerging from both Left and the fat cat Right, but there was also some thoughtful analysis, the best of which was Andrew Sullivan’s April 2017 piece on reaction in New York magazine.

Sullivan’s worthwhile contribution groups reactionaries into three clusters, each with an avatar.

The first avatar is Leo Strauss, who fled Nazi Germany and ended up in California as an obscure and Sphinx-like, but highly influential, political philosopher.

Sullivan does not attempt to directly parse Strauss (unlike Lilla, as we’ll see), but focuses on Charles Kesler, editor of The Claremont Review of Books, as a type of gnomon sub-avatar, revealing the truth cast by the light of Strauss.

In short, according to Sullivan, Straussians think that the modern American political system has wholly lost its way, but that as with the string of Theseus in the Labyrinth, there exists a clear path back to an ideal political system that has, unlike most supposedly ideal systems, actually been tried and found effective.

That is the America of its original Constitution, either as it existed in 1787, or as amended by the post-Civil War amendments. Nobody informed can disagree that today’s American government bears essentially no relation, except in its external forms, to the American government of 1870, no more than the Roman government of A.D. 50 bore to the Roman government of 300 B.C.

Straussians, although they have various internal divisions, believe that the desired end of political history arrived already—and was left behind. Therefore, today’s Cthulhu State, a multi-tentacled horror of unlimited and unaccountable power, exemplified by the monstrous administrative state that finds no warrant in the Constitution, should be destroyed and the Republic restored by the simple expedient of turning back the political clock.

The second group is represented by the avatar of Michael Anton, and was mostly embodied by the belligerent, now defunct pre-election blog, The Journal of American Greatness, which has a quasi-descendant in the still extant American Affairs, an actual journal published by Julius Krein, who had a prominent role in American Greatness.

Anton is in some ways a Straussian, in that he admires the Founding, but he is much more what I would, to coin a term, call an “Augustan” – a man who sees some benefit in democratic forms, but little other benefit in democracy, and who therefore focuses on power and its uses.

In an Augustan system, the forms of republican government remain, and even some of its application, but the real power has shifted. Sullivan terms this “Caesarism,” by which he means to refer to Julius Caesar, not Augustus Caesar (Octavian). But this is the wrong historical parallel.

Julius Caesar technically overthrew the Republic, true, but it was already completely fractured by decades of civil war, and Julius Caesar himself manipulated the actual levers of political power for only a brief time.

We remember him for his death, not his rule. It is Augustus we remember for maintaining the forms of republic while making himself “first among equals,” the first emperor. The Roman Empire is dated from 27 B.C., from recognition of the final victory of Augustus over his enemies, not from any action of Julius Caesar.

Anton wrote the famous “Flight 93 Election” essay prior to the election, insisting that Trump should be the choice, regardless of any faults he might have, for the alternative was certain death, metaphysical and perhaps actual. Anton focuses less on the forms of the government and more on who has the power.

At present, the global elites, the “Davoisie,” have the power, and they use it to benefit themselves at the expense of the mass of people of the Republic (perhaps the entire mass, perhaps the virtuous mass—Anton seems deliberately obscure here).

Anton explicitly calls for Caesar, or rather, says that Caesar has already arrived, if not on horseback, so he might as well be the right Caesar. Rollback is not the goal; the goal is seizing the levers of power as they exist now, and overthrowing the great as the opportunity presents itself, casting them into the pit to wail and grind their teeth. Thus, for Anton, the focus is power guided by virtue, but always power.

The third group, and the one least known to the general public, has as its avatar the computer programmer Curtis Yarvin, often referred to by his pseudonym, Mencius Moldbug.

Whereas Kesler offers an easily comprehensible, if not easily attainable, program; and Anton offers a program that is coherent, if mostly responsive and inchoate (the reader suspects it is not really inchoate in Anton’s mind, though); Yarvin offers the desperation pass with a flaming football, probably one sewn from human skin, and he worships strange gods.

All you really need to know about Yarvin is that he is a self-identified Jacobite – that is, his preferred form of modern government is a restoration in the United States of the Stuart monarchy, via the vehicle first of an all-powerful figure known as the Receiver (a term taken from bankruptcy law), who will smash the Cathedral, the modern all-powerful and unholy alliance of the American elites, whose ax and fasces of power are the combined and interlocking might of the universities and the media.

The Enlightenment will be forgotten as a mistake, and we will have a night watchman state that offers a free press and free economy, true, but which is armed not with a nightstick, but with shoulder-mounted rockets.

While Sullivan draws incisive portraits of each of the three avatars, the rest of his essay is pretty weak. By way of preface, he draws a simplistic contrast between reaction and “real conservatives,” a topic he miserably fails to address with any adequacy (but one which I will on another day address completely).

Next he engages in navel-gazing about his supposed youthful sympathy with reaction, but all he describes is a love for Russell Kirk’s permanent things, and as both he and Lilla point out, reactionaries are not conservatives, so this is mere confusion.

Sullivan then adds his own shallow analysis of reactionary thought, attempting to synthesize his three avatars, or at least to show they share core beliefs. Finally, not digging very deep, Sullivan, as with most critics of reaction, ascribes to it a universal desire across its advocates to return modern society to a supposed past Golden Age – this trope is common to all progressive analysis of reaction.

His analysis strikes me as erroneous from start to finish. As applied to Straussians, there is some thin justice to the claim of desired return, although Straussians would not claim that the Founding inaugurated a Golden Age, merely the best possible political solution for an imperfect world.

But while Sullivan’s other reactionaries see value in the past, and often unfavorably compare the modern world to it, they do not want to return to it, for they are not stupid. They want to get the benefits of the past while keeping the benefits of the modern world; theirs is in many ways a very modern project, open to a changing world and the concept of progress.

It is not for nothing that those who attack reactionaries, such as the increasingly shrill William Kristol, have claimed they resemble the Nazi legal theorist Carl Schmitt in their thought.

I have no idea of the truth of that claim, knowing nothing about Schmitt, and I do not suggest key parallels otherwise, but the nature of all modern radical “right-wing” reformers, of all stripes, is that they call for a march forward, informed by the past, but not into the past.

They have a different definition of where the march should go than does Sullivan, but in an important sense, they are all progressives. Any references to a Golden Age are purely for propaganda purposes, along with using it to provide object lessons to inform action in today’s very different world today. Sullivan mistakes that gleam for the substance; he is not the first progressive led astray by fool’s gold.

In the same vein, Sullivan complains of reactionaries, specifically of Anton, that “their pessimism is a solipsistic pathology.” In Anton, who says the only things in modernity worthwhile are “nice restaurants, good wine, a high standard of living,” he sees a man “deliberately blind to all the constant renewals of life and culture around us.”

But Sullivan does not specify what those renewals are, and for the life of me, I cannot fathom to what he refers. Certainly, a plausible argument can be made that Anton-style pessimism is the wrong response to modernity, or that nice restaurants and wine are, after all, part of the substance of the good life, and not to be denigrated. It does not follow from that that anything is being renewed; the opposite of pessimism can be just as much a comfortable stagnation as illusory “renewals of life and culture.”

While Sullivan seems to think that to pronounce negativity about the modern world is self-refuting, Sullivan’s next paragraphs offer a clue as to what he believes is better about today than yesterday, and it has nothing to with “renewals of life and culture.”

Here, Sullivan resorts to a hackneyed rhetorical trick beloved of today’s progressives. The trick involves making a sanitized list of modernity’s social accomplishments, while ignoring not only modernity’s horrors, but the strongly equivocal nature of many of the supposed accomplishments.

So, we are told, usually in vague, bilious phrases, that (i) certain aspects of life today are better than life yesterday, and that (ii) the beneficiaries of those improvements are individuals who are sympathetic. We are then informed that it necessarily follows that (iii) any criticism of life today is unsympathetic to those individuals, because yesterday they lived in suffering, so therefore (iv) any criticism of life today is beyond the pale.

The reader can guess, from seeing this spurious chain many times before, that Sullivan adduces as better aspects of life today as “unprecedented freedom for women, racial minorities, and homosexuals,” “increased security for the elderly and unemployed,” and a variety of other stock canards about progress.

There is a grain of truth here, but really Sullivan is talking past the reactionaries, not engaging them. He glides past the reality that few of his “improvements” are in fact unmixed blessings, if blessings at all, for often positive changes are balanced by negatives. Then he skates around any negative aspect of modern life, and finally demands we agree that because some things are better for some people in some ways, we must live in the best of all possible worlds, and any criticism of the modern world is an unforgivable attack on the formerly persecuted.

So, for example, there probably is more “freedom for women” today than in 1950 (in the West, that is – implicit in all progressive discussions of reaction is that we are only talking about the West, and it is best to avert our eyes from other areas of the world).

But a real comparison of 2017 to 1950 would require much unpacking, including distinguishing claims of freedoms such as flexibility of employment and reductions in harassment from false “freedoms,” such as, abortion rights, along with an examination of whether women as a whole are better off in the modern world on other measures – and an honest evaluation of whether what “everybody knows” about the world of 1950, implicit in Sullivan’s brief statement, is actually true.

Sullivan’s purpose is not to engage in such a dialogue, though; it is to end any possibility of dialogue by imagining, like the Manichees, a World of Light and a Kingdom of Darkness, and assigning anyone who does not join the progressive crusade to the latter.

I suppose his line of thought could be even more dishonest – Sullivan does not accuse Anton of objecting to antibiotics and electric light. But none of this sheds any light on whether reactionaries have a point, for it assumes that they do not.

So much for Sullivan. His article is relatively brief, and as with most opinion pieces, does not pretend to be a work for the ages.

Lilla, likewise, is not writing for the ages, though his book is longer and much more polished than Sullivan’s article.

At the beginning, Lilla denies that The Shipwrecked Mind is a “systematic treatise on the concept of reaction.” Instead, it is an examination of several individuals, most of whom have no obvious link to each other, and Lilla does not attempt to draw clear links among them. His purpose is instead to draw a general analogy between reactionaries and revolutionaries, referring to his own earlier book, The Reckless Mind, about men in love with revolutionary tyranny.

Lilla begins by pointing out that “Reactionaries are not conservatives. . . . Millennial expectations of a redemptive new social order and rejuvenated human beings inspire the revolutionary; apocalyptic fears of entering a new dark age haunt the reactionary.”

While this is true as far as it goes, it fails on two points. First, as with Sullivan, Lilla never tells us what conservatives are, other than not reactionaries. If we define something by what it is not, we must know what is the thing it is not.

Second, Lilla’s core parallelism fails, for being haunted by fears about the future is not in any way similar to revolutionary thought. The latter is always a self-contained system for achieving Utopia through following the right steps and killing the right people. Fear about the future, in contrast, is only fear and does not imply a program. While reaction can be an ideology, Lilla’s own definition makes reaction simply a recognition that some things were better in the past, not that the past offers a complete solution for the present, or a path to implement that solution.

Lilla does seem to recognize the failure of his parallel, trying to explain “the enduring vitality of the reactionary spirit even in the absence of a revolutionary political program” by the problem that “to live a modern life anywhere in the world today . . . is to experience the psychological equivalent of permanent revolution.”

At that high level of generality this is true enough, and it sounds like Zygmunt Bauman’s “liquid modernity.” But it says nothing about whether reactionaries themselves have an ideology or system of thought that is revolutionary in nature. It merely explains why neoreaction has an attraction for some people. And Lilla himself concludes that reaction “is unsure how to act in the present.”

A system of thought unsure how to act is essentially the antithesis of an ideology, and thus in no way establishes the parallel for which Lilla is reaching.

But enough definitional games. Let’s examine the core of this book, which is the thought of men Lilla identifies as relevant to reactionary thought.

He begins with one truly obscure, Franz Rosenzweig (1886–1929), a theologian of German Jewish extraction, who, raised indifferently religious, nearly converted to Christianity and then returned to devout Judaism. He seems like an odd choice, for Rosenzweig is mostly known for a difficult mystical tome, The Star of Redemption.

Lilla argues, elliptically, that in Rosenzweig’s linkage of Christianity and Judaism as bound together eternally, “the Jews are a people that see the light but [are] unable to live in it temporally, while Christians live in an illuminated world but cannot see the light itself.”

Quite fascinating, but what it has to do with reaction is not clear. Rosenzweig apparently did not see a past Golden Age, other than that Judaism is true, always has been, and always will be, nor did he maintain a political program.

Lilla next turns to Eric Voegelin (1901–1985), another German. He was the author of the phrase “immanentize the eschaton,” used as a criticism of modern Utopian political schemes, and one of the first to enunciate the truism that twentieth-century radical politics was religious in inspiration and form.

Voegelin was an intellectual polymath, so it is hard to say that he had a single focus, but according to Lilla, one of his focuses was the relation between religion and politics. He said, accurately, “When God has become invisible behind the world, the things of the world become the new gods.” His views led him to attack the Nazis as precisely such idol worshippers, and unsurprisingly, he was forced to flee to the United States, where he stayed.

Lilla’s main purpose in including him here is to note that while for most of his life Voegelin hewed to a narrative of modern decline resulting from the rise of political religions, in his final years he “rejected” this. But in Lilla’s description, it sounds more like Voegelin went off the rails into incoherent mysticism combined with even more splintered focus than before.

On little evidence, at least that he offers, Lilla concludes that “It takes a good deal of self-awareness and independence of mind to renounce the bittersweet comforts of cultural pessimism and question the just-so narratives of civilizational decline that still retain their allure for Western intellectuals.”

Maybe, but as with Sullivan, this seems a weak response to an illusory narrative by offering conclusions without reasoning. Lilla keeps banging on about “cultural pessimism,” but rather than showing why and how this matters, instead concludes that anyone who is unhappy about any aspect of the modern world necessarily beclowns himself in a way not needing demonstration.

Moreover, Voegelin seems put in this book not so much as an example of a reactionary as to lecture Americans that smart people turn away from narratives of decline.

The author then profiles Strauss (1899–1973), yet another German émigré to the United States. Strauss is notoriously oblique in his thought. He is often accused of deliberately introducing layers of gnosis into his philosophy, including a hidden call for instrumental use of religion by philosophers and rulers, and endorsing undemocratic governance by an educated elite.

According to Lilla, “Strauss and Heidegger shared one large assumption: that the problems in Western civilization could be traced to the abandonment of a healthier, ur-mode of thought from the past. . . . [He] spent much of his career trying to establish the decisive point when the great deviation took place.” Strauss found it in Athens, specifically Plato, with a nod to Jerusalem.

All interesting, but what does this say about American politics, a topic on which Strauss never focused at all? One of Strauss’s seminal works was the 1953 Natural Right and History, in which Strauss identified where modernity broke the world.

“Strauss claimed that, properly viewed, there had been a single coherent tradition of ‘classical natural right’ running from Socrates to Thomas Aquinas. This tradition made a strict distinction between nature and convention, and argued that justice is that which accords with the former, not the latter. Whether the rules of nature are discovered through philosophy or revelation, whether one account of nature is more persuasive than another, all this is less important, according to Strauss, than the conviction that natural justice is indeed the standard by which political arrangements must be judged.”

And it was Machiavelli who destroyed this tradition, which should be restored by returning to classical thought as the lodestone of political action. Strauss’s philosophy was, after his death, picked up by a variety of his students and molded into a claim, as far as I can tell, that the Founders based their construction of America on classical philosophy and natural right, and that, largely as a result, what they created, either initially or as modified after the Civil War, is the ideal political system.

But again, this is not a Golden Age program – it is a prescription for political structure.

Lilla’s next essay is an attack on Catholicism, in general and especially inasmuch as it provides an incubator for reactionaries. It’s pretty clear throughout the book, in fact, that Lilla is hostile to Christianity as a whole, for reasons not really clear, though this is the only section in which his prejudice is made explicit.

He claims, without example, that the usual Catholic practice is to adapt doctrine to radical change by, after a period of resistance, “declaring that such innovations had been continuous with Catholic doctrine after all.”

Then, he denigrates formal Catholic thought as merely “a stream of papal encyclicals that reflect the shifting moods of this or that pontiff,” with any relevant thought being provided by lay intellectuals (here, as elsewhere, Lilla seems to be only dimly familiar with any pre-Enlightenment history or thought).

No doubt the Catholic Church is a bastion of reaction; it is in its nature. It offers a coherent world view developed over two thousand years, one that necessarily opposes many aspects of modernity. But as with a great deal of what Lilla says, his conclusions don’t follow from the listed facts.

Lila’s purpose here is to attack the supposed philosophy of “The Road Not Taken,” in which a variety of Catholics over the past five hundred years have complained that the (Western) world took a wrong turn, with a radical break from the medieval tradition in which Catholic, and therefore Western, thought was developed to a peak.

In other words, although Lilla does not say this, Strauss points to Athens, and these thinkers point to the High Middle Ages, as the time when political thought reached its point of maximum refinement.

Among such thinkers are Étienne Gilson, who wrote Reason and Revelation in the Middle Ages, Hans Urs von Balthasar, and Henri de Lubac.

Lilla makes a positive nod to the thought of these men, but mostly in order to create a contrast to his attack on two more recent thinkers, Scottish philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre and Brad Gregory, currently a professor of history at Notre Dame.

The goal here is to identify these authors as agents of the Vatican eager to impose retrogression on modern man. Lilla’s is merely a more glossy version of Sullivan’s bogus chain of reasoning, identifying prospective victims of a proposed reaction whose terror at moving backwards gives them moral superiority and a hall pass from reasoning.

Lilla does write better than Sullivan, though (my favorite line is when Lilla, referring to Gregory’s The Unintended Reformation, says “But the deeper you delve into this book, the more you begin to feel that you are watching a shadow-puppet play on the wall of some Vatican cave”).

Lilla complains Gregory’s book is not, as it should be, a “straightforward history,” but rather “a sly crypto-Catholic travel brochure for the Road Not Taken.” Those tricksy Catholics! (I bet Lilla would react with displeasure, though, if somebody referred to “a sly crypto-Jew.”)

Lilla’s basic point about Gregory is another mess of confused reasoning – he identifies claims Gregory makes about the past that are summary in nature, such as that before Duns Scotus and William of Ockham, “traditional Christian metaphysics” dominated Western thought, and then Lilla waves his hands about “centuries of disagreement,” claiming “it is hard to know . . . . how such a metaphysics manifested itself at a popular level,” and finally concluding that we can’t know anything, and therefore Gregory is a chump to claim any coherency about the past, that he lives in “a narcotic haze.”

None of this is convincing, in part because although Lilla is addicted to using Christian metaphors, he appears to know next to nothing about actual Christianity, except what he learned in Steven Pinker books.

If he did, the various terms that befuddle him would have obvious meaning and content, but that would require engaging with a religion for which he has a clear distaste.

Gregory may not be right, but even in Lilla’s summary, he is very much logical and plausible. For Lilla, though, any summaries of the past that are offered to inform the present are just “an imaginative assemblage of past events and ideas and present hopes and fears.” As with so much Lilla says, there is some truth in this (not that Lilla offers anything other than his bare statement), but he uses it to serve his own philosophy (very much in evidence in his most recent book, on identity politics, The Once and Future Liberal), that any system of thought that offers any type of ultimate answers, or suggests that civilizations have peaks and valleys, is the sandbox of fools.

True, Gregory and MacIntyre are thinkers who actually do talk a lot about a Golden Age, unlike the other philosophers Lilla discusses. But Lilla is wrong that their project is “escaping full responsibility for the future;” he only says that to support his own philosophy – that the past is largely irrelevant, because “we are destined to pave our road as we go.”

Lilla ends with two essays, one on current events, the other on a fictional character.

The current event was the 2015 Charlie Hebdo shooting in Paris, which Lilla uses as a springboard to discuss two French reactionaries, Éric Zemmour and Michel Houellebecq.

Here Lilla has interesting things to say about what an ideology is, including the keen insight that “they are first developed in narrow sects whose adherents share obsessions and principles, and see themselves as voices in the wilderness. . . .But for an ideology to really reshape politics it must cease being a set of principles and instead become a vague general outlook that new information and events only strengthen.”

Zemmour, in Lilla’s description, offers just such a shotgun approach to politics, combining controversial, but factual, claims with various wild allegations and fringe, yet flexible, positions.

Houellebecq is profiled mostly for his novel Submission, about a near-future France that turns to Islam as Western culture peters out (although, oddly, Lilla says the title is “shockingly blunt,” apparently unaware that the literal translation of “Islam” is “submission,” i.e., to Allah).

Lilla offers the insight that “Houellebecq’s critics have seen the novel as anti-Muslim because they assume that individual freedom is the highest human value – and have convinced themselves that the Islamic tradition agrees with them.

It does not, and neither does Houellebecq.” (This panicked exaltation of extreme individual freedom, and the claimed need for immigrants to conform to it, is largely the topic of Rita Chin’s recent The Crisis of Multiculturalism, and is the key to understanding the modern European mindset).

This essay sheds little light on America (Lilla seems to much prefer talking about Europe and Europeans, although if he wanted to talk about a focus on a past Golden Age, he would have done well to throw Confucianism into the mix), but it does penetrate closer to what reaction actually is.

Finally, we are treated to a discussion of Don Quixote. The Ingenious Nobleman’s undoubted desire to return to a Golden Age is supposed to show, again without reasoning, that any person who today sees value in the past (which is basically how Lilla defines reactionaries) is a fool who tilts at windmills.

Most of the discussion here is not about Western reaction, though, but Muslim reaction and Golden Age thinking. In essence, but without naming him, Lilla summarizes the philosophy of Sayyid Qutb, accurately. But this has nothing to say about the West, except as it threatens the West.

So often in this book, Lilla talks about how Western reactionary thinkers want to return us to a Golden Age, but every time he reaches for a concrete example, he can only offer fringe Muslims, relevant purely because of their willingness to use violence.

Lilla seems to think that Don Quixote is, like Strauss, an avatar of reaction who represents what real people believe in the real world. Someone is living in a fantasy world, but it’s not Don Quixote, because he’s not real.

While sonorous, this essay is gloriously free of both reasoning and substance, and adds nothing to Lilla’s core argument, which is (probably because all these essays were first published separately), ultimately laughably incoherent and weak, and even the biographies and history in The Shipwrecked Mind are neither original nor illuminating.

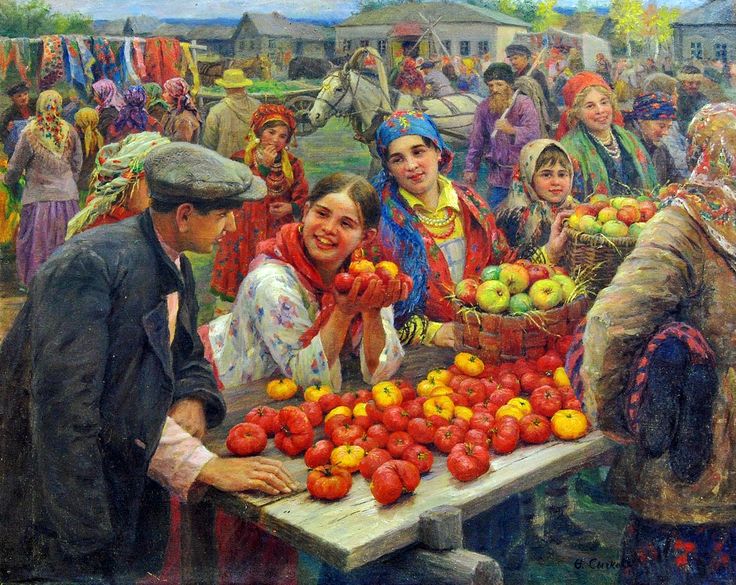

The photo shows, “The Menin Road,” by Paul Nash, painted in 1919.

Charles is a business owner and operator, in manufacturing, and a recovering big firm M&A lawyer. He runs the blog, The Worthy House.