The President Of The Fifth Republic – Gaullian Thought

With his followers, de Gaulle created, in 1947, the Rassemblement du Peuple Français (RPF), a movement which initially had a good number of members elected to the Assembly, but which then declined until its dissolution in 1953. During these years, the General was wary, in particular, of the influence of the PCF, the Communists and their leaders, of whom he regularly said that they were in the service of the USSR, that they had a project of domination of Europe, and that their aim, unspoken and underhanded, was to submit the country to foreign domination.

In 1951, de Gaulle rejected the supranational character of the European Coal and Steel Community (CECA) and opposed in the name of national sovereignty, a project of the European Defense Community (EDC). On the other hand, he rallied to the idea of European integration and approved the entry of France into the European Economic Community (EEC), following the signing of the Treaty of Rome in 1957. Being a man of letters since his youth, he took advantage of the political lull that followed to write the three volumes of his Memoirs which he published in 1954, 1956 and 1959.

De Gaulle, An Exceptional President Of The Republic

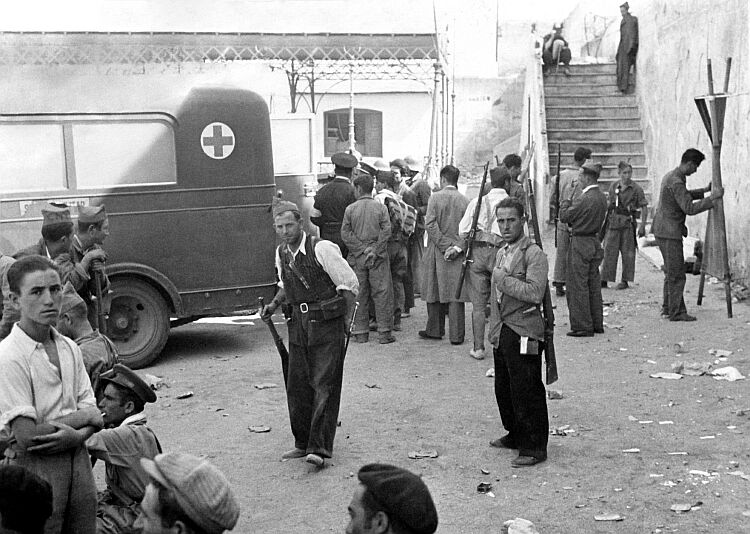

At the beginning of 1958, events in Algeria began to escalate. Fear and anger gripped the French in Algeria, as well as chiefs of staff of the army, as rumors circulated about negotiations between the government and the FLN separatists. On May 13, a big demonstration was planned in Algiers. To calm the crowd, General Massu, a lifelong Gaullist, chaired a committee of public safety and demanded that in France a government of public safety be formed, chaired by General de Gaulle.

On the 15th, General Salan harangued the crowd and exclaimed, “Vive de Gaulle!” On May 16, in Paris, at the Palais Bourbon, the socialist leader, Guy Mollet, rallied to de Gaulle’s solution. After being received on May 29 by the President of the Republic, René Coty, who entrusted him with the task of constituting the government, de Gaulle appeared before the National Assembly on June 1st to receive the investiture of President of the Council, along with extended powers, with a view to preparing new institutions (329 votes for, and 224 votes against).

In June 1958, de Gaulle made a trip to Algeria, where he uttered those unhappy words: “I understand you” (speech from Algiers, June 4, 1958) and “Vive l’Algérie française” (speech from Mostaganem, June 6, 1958). He falsely gave the impression of committing to French Algeria and assimilation. The French of Algeria, and many senior officers, never forgave him for fostering the misunderstanding in this way. In fact, de Gaulle understood that France no longer had the energy necessary for an imperial destiny. He anticipated the danger of an invasion of the metropolis by large African populations, with a conquering Islamic religion. He also knew that the world had changed and that France and Europe would have to establish new relationships with the peoples of the former colonies, based on interdependence and respect for differences.

From August 24, 1958, de Gaulle began, in Brazzaville, the process of the decolonization of black Africa, by suggesting that a community of autonomous Franco-African States would succeed the colonial empire. This “French Union” would be the crucible for the independence of the states of French-speaking black Africa two years later. Fourteen French-speaking African states thus achieved independence. September 16, 1959 was a turning point in Algerian politics. In a speech de Gaulle proposed “the right of Algerians to self-determination.”

On January 8, 1961, the French approved, by referendum, the principle of self-determination, and thus the independence of Algeria. In response, the French in Algeria revolted; in Algiers it became known as “barricade week” (January 24 – February 2). But on April 8, 1962, 90% of the French approved, by referendum, the Evian agreements, providing for the independence of Algeria.

On April 22, 1961, an attempted military coup broke out in Algiers; it failed after four days, because the army mostly remained loyal to de Gaulle. Many Gaullists, resistance fighters from the start, such as the ethnologist, ex-minister, Jacques Soustelle, or the sociologist, Jules Monnerot, author of Sociologie du communisme (a classic of 20th-century thought, published in 1949 and expanded in 1963) were now moving away from de Gaulle. Others, such as the minister and future prime minister Michel Debré, who had initially been a supporter of French Algeria, or the political scientist, Julien Freund, author of the most important French political work of the twentieth-century, L’essence du politique, remained inextricably linked to Gaullism.

It appeared that de Gaulle’s position was dictated by the need to protect France from being conquered by Islam, as Malraux had described to him. In March 1959, two months after his installation at the Élysée Palace, de Gaulle gave his intimate thoughts to Alain Peyrefitte, concerning the reasons which led him to offer independence to Algeria: “It’s very good that there are yellow French, black French, brown French. They show that France is open to all races and that it has a universal calling. But only on the condition that they remain a small minority. Otherwise France will no longer be France. We are nevertheless above all a European people of the white race, of Greek and Latin culture, and of the Christian religion… Let’s not tell each other stories! Muslims, have you seen them, with their turbans and djellabas? You can see that they are not French! Those who advocate integration have the brains of hummingbirds (he then thinks of his ex-friend, Soustelle), even if they are very learned… Integration is a trick to allow Muslims, who are in the majority in Algeria ten to one, to find themselves in the minority in the French Republic one to five. It’s a childish sleight of hand! We imagine that we can handle the Algerians with such jackass tomfoolery. Can’t you see that the Arabs will multiply by five and then by ten, while the French population will remain almost stationary? Then will there be two hundred, then four hundred Arab deputies in Paris? Do you see an Arab president at the Élysée?… We will perhaps realize that the greatest of all the services that I have been able to render to the country was to detach Algeria from France; and that, of all, it was this very service which hurt me the most. With hindsight, we will understand that this cancer was going to do away with us. We will recognize that the ‘integration,’ the faculty given to ten million Arabs, who would become 20, then forty [they are now more than 42 million, NDLA], to settle in France as at home – it will be the end of France.”

In May 1963, in the Council of Ministers, he insisted again: “I draw your attention to a problem which could become serious. There were 40,000 immigrants from Algeria in April. This is almost equal to the number of babies born in France during the same month. I would like more babies to be born in France and less immigrants to come. Let’s not overdo this! It is urgent to put it in order!” No politician today would dare to open such a debate with the arguments used previously by de Gaulle, without risking a humiliating defeat at the hands of censors and inquisitors, modern guardians of mono-thought – worse, without immediately suffering the wrath of the law.

Be that it may, the French were indebted to the General for the end of the Algerian war. He alone had managed to resolve the terrible conflict that had torn France apart for years. But the conditions under which he did so and the methods he employed remain debatable and debated. De Gaulle would say at the end of his life about Franco, “All things considered, the results of his action are positive for his country. But, God, he had a heavy hand.” It is probably no exaggeration to repeat his harsh words here when we consider the tragedy experienced by the Harki and the French in Algeria.

On October 28, 1962, after a political crisis of exceptional violence, which brought together supporters of a referendum and opposition parliamentarians demanding the revision of the Constitution via the majority of Congress, the National Assembly was dissolved. De Gaulle finally won and a popular referendum was organized on the election of the President of the Republic by universal suffrage. The project was approved by the people with 62.25% of the votes in favor. De Gaulle always wanted to exclude the middlemen of the political caste, who were too indifferent to the concerns of the people. It is therefore not surprising that he saw “all the cripples of contemporary history” rise up against him – a vast and heterogeneous coalition of professional politicians, ranging from radical and traditional right-wingers, to Liberals and Christian Democrats. Socialists and Communists.

Nevertheless, Gaullism did have the advantage of bringing together politicians whose origins and convictions were numerous: Jacobins, Conservative administrators, reformist Liberals, radicals, social democrats, left-wing republicans, even far-left, independent intellectuals, technocrats, Maurrassians and nationalist disciples of Péguy or Barres. Sociological Gaullism went far beyond the moderate Right electorate (liberal-conservative and Christian-democratic) and the radical Right. It rallied a large fraction of the Left electorate, seduced by the charisma of the General and by his desire to reconcile order and progress.

At that time, pamphlets, published by prestigious publishing houses, were successfully circulated against de Gaulle. At the end of the Second World War, in 1945, Henri de Kérillis, a Giraudist residing in the United States, published, in Montreal, De Gaulle, dictateur (De Gaulle, Dictator).

In 1964, it was the right-wing anarchist, Jacques Laurent, who published, Mauriac sous de Gaulle (Mauriac under de Gaulle), a libelous work in which he blamed “the Chief who exercises absolute power,” and even claimed that France “lives under a form of tyranny.” The partisans of French Algeria did not forgive him for having had Colonel Bastien Thierry, leader of the conspirators, shot after the attempted assassination at Petit-Clamart, on March 11, 1963. Parliamentarians and former ministers, like the now old Paul Reynaud (right-wing Centrist), Gaston Monnerville (Democratic Left), or François Mitterrand (UDSR – Democratic and Socialist Union of the Resistance) were not the least virulent.

Paul Reynaud declared that President de Gaulle had violated the Constitution and insulted Parliament. In 1964, Mitterrand published his pamphlet, Le coup d’État permanent (The Permanent Coup d’etat), in which he denounced the practice of “personal power” and the weakness of the marginalized parliament. He called for voting “No” in the referendum on the Constitution of the Fifth Republic (1958) and “No” in the referendum on election by universal suffrage (1962).

François Mitterrand was then known for the attack at the Observatory, a false attack carried out against himself in 1959 [the “Observatory Affair”]. Being then a minister of the Fourth Republic, which was then in decline, Mitterrand had ordered this attack as an attempt to regain some public confidence. De Gaulle, who sometimes was ferocious, gave him various unflattering nicknames, such as, “Rastignac de la Nièvre,” (a social-climber of Nièvre ), “the Arsouille” (thug), or “the Prince of political dogs.” Indicted for “contempt of court,” Mitterrand took advantage of an amnesty law passed by the Pompidou government (the 1962 law; brought into force in 1966), which stopped the legal proceedings against him in 1966.

The reference to the coup d’État to censor the arrival and exercise of power by de Gaulle was a leitmotif of his opponents. We know that European Liberal and Socialist traditions have been marked by numerous recourses to putsches, coups d’état and other pronunciamientos (the first in the 19th-century, and the second at the turn of the 20th-century).

But the fact remains – after the Second World War, in the name of representative democracy, the representatives of these two tendencies sought to sanctify the democratic legitimacy of power (at the expense of the legitimacy of its exercise). De Gaulle, who did not allow himself to be fooled by their legal quibbles, said in this regard: “A good number of political professionals… refuse to see the people exercising sovereignty over the role of these professionals as intermediaries.” But paradoxically, history has shown that de Gaulle was much more democratic than his successors. It was with dignity, and without making the slightest comment, that he left office in 1969, after a referendum on Senate reform and regionalization was rejected by 52.41% of the vote.

Conversely, in 1986, when the legislative elections brought to power a right-wing majority, the socialist François Mitterrand, however critical of the institutions of the Fifth Republic, remained in his post and brought in Jacques Chirac as prime minister, which made for both unnatural and sterile marriage. In 1997, in the wake of the unfortunate dissolution of the Assembly, Chirac also remained at the Élysée, bringing in the Socialist Lionel Jospin as prime minister. In 2005, again, after losing the referendum on the draft European constitution, Chirac was careful not to head to the exit door.

Finally, in 2007, Nicolas Sarkozy had the National Assembly ratify the Treaty of Lisbon on the new European Constitution, with the help of the Centrists and the Socialists, while it was rejected by the people in the referendum of May 29, 2005. No referendum has ever been held since. The concept of democracy held by the heads of state who succeeded de Gaulle is, to say the least, of a variable geometry.

In addition to the institutions of the Fifth Republic, a heritage on which the French still live, one must add to de Gaulle’s successes national independence (with the nuclear deterrent force, the withdrawal from NATO’s integrated command, and the return to major economic and financial balances), Franco-German reconciliation (Franco-German friendship treaty of January 22, 1963), and the ordinances on employee profit-sharing and ownership (January 7, 1959 and August 17, 1967). These reforms allowed “collective participation in the running of the company or establishment… participation in the capital or in self-financing operations… [and] participation in the increase of productivity.”

In de Gaulle’s eyes, participation was to crown his social work. But it would come up against the joint hostility of the employers, who feared the arrival of Soviets in the company, and of the unions, who saw all co-management as a phenomenon of class collaboration.

Finally, it should be noted that after the direct intervention of his wife, Yvonne, de Gaulle, agreed to support Deputy Lucien Neuwirth’s law authorizing the use of the contraceptive pill. At the Council of Ministers of June 7, 1967, de Gaulle, hesitant and even reluctant, still said, according to Alain Peyrefitte, “Morals are changing, we can do next to nothing.” But “we must not make social security pay for the pills. These are not remedies! The French want greater freedom of morals. We’re not going to reimburse them for this trifle!” The law authorizing the sale of the contraceptive pill would finally be adopted in December 1967. And it was in 1974, under the presidency of the liberal-conservative, Giscard d’Estaing, that the Minister of Health, Simone Veil, allowed social security to reimburse the pill.

On December 19, 1965, de Gaulle was re-elected President of the Republic, defeating François Mitterrand by 54.5% of the vote. This second term would be marked by three virulent controversies, which have remained famous, and which go far beyond France itself. After the end of the Algerian war, de Gaulle could fully denounce any form of colonization, and he did not hold back in this denunciation by supporting policies of independence, balance, peace and non-alignment, while defending the principle of territorial integrity.

While the United States was fighting in Viet Nam, in a speech in Phnom Penh on September 1, 1966, de Gaulle criticized American intervention and asserted the right of peoples to self-determination. On July 24, 1967, in a speech in Montreal, he supported the interests of the “French in Canada” and the sovereignty of Quebec (“Vive le Québec libre!”) – which did not fail to shock English-speaking Canadians (Time called him a “senile dictator”), but also a large part of the political and media establishment of France who showed their strong disapproval. (This was particularly the case with Le Monde, Le Figaro and anti-Gaullist politicians, such Pleven and Lecanuet, but also Gaullists, such as, Prime Minister Georges Pompidou, who considered the remarks excessive).

However, it was undoubtedly the press conference of November 27, 1967, five months after the Six Day War (June 5 to 10, 1967), during which de Gaulle called the Jewish people “an elite people, self-assured and domineering,” and condemned Israel for attacking Arab countries, which aroused the most passions.

De Gaulle took a position against most political leaders and the mainstream media, which led to a deluge of venomous criticism. (Such as the directors of Le Monde [Hubert Beuve-Mery], of the Nouvel Observateur [Jean Daniel], and of l’Express [Jean-Jacques Servan Schreiber], but also the editors of Populaire of the SFIO, of l’Aurore, and of Figaro). Raymond Aron even went so far as to criticize him for “rehabilitating anti-Semitism,” a hysterical accusation vigorously refuted by David Ben-Gurion.

In fact, de Gaulle regarded the creation of Israel as “a historical necessity,” and “a fait accompli.” He added, “We would not want Israel to be destroyed.” And later said, “France will help you tomorrow, as she helped you yesterday, to maintain you, no matter what. But it is unwilling to provide you with the means to conquer new territory. You have achieved a feat. Now don’t overdo it.” De Gaulle refused the conquest of territories by force and affirmed the need for dialogue with the PLO (Palestinian Liberation Organization) and the right to self-determination of the Palestinians.

But nothing suggested that less than six months later he would be facing riots, initiated by leftist, libertarian and Marxist students, and which would then be taken up by the entire left-wing opposition. This was the time when the philosopher, and Maoist sympathizer, Jean-Paul Sartre, complacently interviewed the libertarian (future liberal-libertarian) Daniel Cohn-Bendit in the columns of the Nouvel Observateur (May 20, 1968).

Sartre, defender of the dictatorships of the East, of the USSR or of Mao’s China and even a declared supporter of the Soviet concentration camps, wanted to be revolutionary. He was not an inspirer of the ’68 revolt, but it was echoed widely in the streets, on the stands and in the newspapers. Crowned with his past as a resistance fighter, an escapee from a Stalag and a defender of leftist causes, Sartre was the icon of the intelligentsia and much of the French university.

De Gaulle respected the “philosopher,” although the author of Les mains sales kept calling him a “fascist,” “pimp,” “piece of shit,” “moron,” “bastard” and “pig.” It would take almost thirty years for the veil to be finally lifted on Sartre’s baseness and villainy. We eventually learned that the legend of the model couple Sartre-Beauvoir did not correspond to reality.

Sartre had never been a resistance fighter; he had twice refused to attempt to escape Germany; he had most likely been released thanks to the intervention of collaborationist, Pierre Drieu La Rochelle. Sartre had signed the two Vichy forms by which he certified that he was neither a Jew nor a Freemason; he had been appointed to the Lycée Condorcet to the post once occupied by a Jewish teacher prohibited from teaching by Vichy laws. Finally, Sartre had written in the collaborationist review Comoedia and his play, Les Mouches (1943) – so-called resistance – had not given him any serious problem with German censorship.

As for his partner, Simone de Beauvoir, she had worked for Radio-Vichy and was not been expelled from the National Education Department by the Vichy government for an act of resistance, but following a complaint of corrupting a minor by Nathalie Sarraute’s mother (See the edifying account of their lives and their pitiful relationships given by Michel Onfray in Les consciousness réfractaires). All in all, they were a couple of mediocre, cowardly, opportunist, careerist, scheming and ambitious “bastards,” to use the pleasant term Sartre and Beauvoir used for their opponents.

“Reform yes, a shambles, no” de Gaulle would say in private, in 1968. In truth, he never forgave himself for letting these events take him by surprise. According to his son, Philippe, he confessed: “I failed. I failed because it is characteristic of someone who governs according to plan. And there, I didn’t see anything, I didn’t plan anything. Of course, I was not the only one in this case… But that’s no excuse.”

On May 27, 1968, a few hours after taking part in the meeting at the Charléty stadium (organized, among others, by the UNEF, the PSU and the CFDT), François Mitterrand proposed the formation of a “provisional management government” headed by Mendès France. But the old lion woke up and finally came to his senses.

De Gaulle, assured of the support of the armed forces of the Republic, after his impromptu visit to General Massu on May 29, 1968, returned to Paris and called for civic resistance. The next day, a gigantic demonstration of nearly a million people gathered on the Champs Élysée to defend the institutions. On June 30, parliamentary elections marked the opposition’s failure. The Gaullists and their allies then won the absolute majority of seats in the Assembly: 358 out of 485.

But this victory would be marred a year later by the success of “No” in the referendum on regionalization, immediately followed by the resignation of the first President of the Fifth Republic. From April to September 1970, de Gaulle published a collection of speeches and messages, followed by his Memoirs of Hope. He died at La Boisserie on November 9, 1970 at 7:30 p.m.

On September 10, 1966, aboard the cruiser, De Grasse, Charles de Gaulle had confided to his minister, future memorialist, Alain Peyrefitte, these few words, which define the essence of Gaullism: “We have tried to invent a new regime, a third way, between oligarchy and democrappy.”

Some Reflections On Gaullian Thought

At the center of Gaullian thought is the desire to reconcile idea of national identity with social justice. De Gaulle knew that one cannot ensure freedom, social justice and the public good without simultaneously defending national sovereignty and independence (political, economic and cultural).

The strength of Gaullism lies in its passion for the greatness of the nation; its aspiration for national unity; its praise of the heritage of Christian Europe; its demand for Europe, from Brest to Vladivostok; its resistance against any foreign domination (American or Soviet); its non-alignment on the international level; its direct democracy (universal suffrage and the popular referendum); its anti-parliamentarianism; its ideal of the third way, neither capitalist nor collectivist; its indicative planning, its “ordoliberalism;” its capital-labor association or participation; and its selective immigration and national preference.

The many links that de Gaulle forged during the 1930s, with various politico-intellectual circles, contributed to the formation of Gaullist Tercerism. From his family roots, de Gaulle very early on received the imprint of double social Catholicism (that of traditionalists, such as, Armand de Melun, Albert de Mun, René de la Tour du Pin, and that of liberals, such as, Ozanam and Lammenais). He also read Maurras in the 1910s, like many officers of his generation; his father was also a supporter of Action Française.

But while he recognized the primacy of foreign policy, and the traditional view of the struggle of states, with an indifference to ideologies that pass away while nations remain, along with anti-parliamentarianism, the strong state and the exaltation of national independence, proclaimed by the “master of Martigues,” de Gaulle also rejected full nationalism and, in particular, state anti-Semitism, preferring instead the philosophy of Bergson, the mystique of the republican idea of Péguy and the nationalism of Barrès ( the author of The Faith of France). Like Barrès, de Gaulle defended the idea of a unitary national history that included the Ancien Régime and the Revolution of 1789, and in which the Republic was a given. Being a subscriber to the Cahiers de la Quinzaine, before the First World War, de Gaulle expressly claimed Péguy as one of his masters. Let us also not forget one of his favorite authors, François-René de Chateaubriand, whom he read and reread his entire life.

In the 1930s, de Gaulle attended the literary salon of Daniel Halévy, historian and essayist, a great connoisseur of Proudhon (anarchist), Sorel (syndicalist-revolutionary) and Péguy (Catholic nationalist). He also participated in the meetings of the circle of an old retired soldier, a Dreyfusard and nonconformist, Colonel Émile Mayer. Close to the socialist left, Mayer made him meet, in addition to his future friend, the lawyer Jean Auburtin, several politicians, such as, Paul Reynaud, Joseph Paul-Boncour, Marcel Déat, Édouard Frédéric-Dupont, Camille Chautemps, Alexandre Millerand and Léon Blum. It was thanks to Colonel Mayer that he came into contact with Daniel-Rops (Henry Petiot). All this new knowledge allowed him to give more resonance to his military writings.

De Gaulle also took part in meetings and conferences of the Ligue de la Jeune République, an organization for political resurgence, after its condemnation by Pius IX, in favor of the Sillon, the progressive Catholic movement of Marc Sangnier. In 1933, de Gaulle contributed to the debates organized by L’Aube, a newspaper close to the CFTC (Christian Trade Unionism in France), which was later chaired by Georges Bidault.

In 1934, de Gaulle subscribed to the review Sept, created by the Dominicans; then, in 1937, to its successor, the weekly, Temps Présent, while he also belonged to the association, Amis de Temps Présent (Friends of Temps Présent). Openly Catholic, these two reviews and their circle, were politically in the center-left. Finally, and above all, a decisive factor in the formation of de Gaulle, undoubtedly much more important than his contacts with representatives of the Christian Democrats, Charles de Gaulle spent time with members of the Ordre Nouveau (O.N.). He regularly attended O.N. meetings, a personalist think tank which, along with the Jeune Droite, and Esprit magazine, was one of the three main streams of “non-conformists of the 1930s.”

Created by Alexandre Marc-Lipiansky, Arnaud Dandieu and Robert Aron, the Ordre Nouveau published, from May 1933 to September 1938, an eponymous review, which claimed to be a third social path, and which wanted to be anti-individualist and anti-collectivist, anti-capitalist and anti-communist, anti-parliamentary and anti-fascist, anti-warmonger and anti-pacifist, patriot but not nationalist, traditionalist but not conservative, realist but not opportunist, socialist but not materialist, personalist but not anarchist, and well, human but not humanitarian. In the area of economics, it was a question of subordinating production to consumption. The economy, as it was conceived by the editors of the journal Ordre Nouveau, must include both a free sector and a sector subject to planning. “Work is not an end in itself.” The “neither Right nor Left” approach of the journal and the group gave itself the objective of placing institutions at the service of the person, of subordinating to man a strong and limited state, modern and technical.

We find in this “non-conformism of the thirties,” as in Christian social thought, three fundamental themes that were dear to de Gaulle: the primacy of man, the refusal of standardization, and the concern for respect of the individuality within community; which implies, of course, an important place given to the principle of subsidiarity. In an interesting article in Figaro, “De Gaulle à la lumière de l’Histoire ,” [“De Gaulle in the light of History”], (September 4-5, 1982), the Gaullist and Protestant historian, Pierre Chaunu, drew my attention, for the first time, to the similarities and convergences which exist between the thought of General de Gaulle and those at the same time of the French non-conformist personalists, of the Spanish national-trade unionist, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, and of various authors of the conservative German Revolution. This striking parallelism is also found in the case of the thought of Eamon de Valera, the founder of the Irish Democratic Republic, and leader of Fianna Fáil. But it still takes a minimum of openness to admit this, without sinking into caricature and propaganda.

In fact, these political aspirations, which have as a backdrop the themes of “civilization of the masses” and “technical society” (dealt with in particular by Ortega y Gasset) are found among a great many European intellectuals of the 1930s who are not reactionaries, but who seek a synthesis, a reconciliation in the form of dialectical transcendence: “To be on the left or to be on the right is to choose one of the innumerable ways available to man to be an imbecile; both, in fact, are forms of moral hemiplegia,” wrote José Ortega y Gasset in his Preface for French readers of La Révolte des masses (1937).

Like all these thinkers, de Gaulle was in no way a reactionary conservative. He admitted to the civilization of the masses and to technology; there was no pastoral nostalgia with him. Gaullism and the personalism of the nonconformists of the 1930s only really diverged in the conception of the nation: the Gaullian defense of the unity, independence and sovereignty of the nation is opposed to the European federalism of the personalists. The fact remained that de Gaulle would always seek to defend a political doctrine that went in the same direction as that of the personalists, marked by the desire to go beyond the Right and the Left.

Throughout his life, de Gaulle sought to find a new system, a “third way” between capitalism and communism. In 1966, when he seemed interested in Walter Eucken and Wilhelm Röpke’s ordo-liberalism, he wrote to Marcel Loichot: “Perhaps you know that for a long time I have been looking, or groping about, for practical way of determining change, not in the standard of living, but in the condition of the worker. In our industrial society, it must be the beginning of everything again, as access to property was in our old agricultural society.” All his life he always refused to position himself on the Right-Left axis. For him, the Right or the Left were only political references that were completely foreign to him. “To be a Gaullist,” he said in 1965, “is to be neither on the Left nor on the Right. It is to rise above. It is to be for France.” And, again, “France is all at the same time. It is all French people. France is not the Left! France is not the Right!… Now, as always, I am not on one side, I am not on the other, I am for France” (12/15/1965).

In the 1930s, de Gaulle did not consider the social question to be primordial. A senior officer needed to focus first and foremost on the implementation of the best means for the independence of the nation. In a letter of November 13, 1937 to his friend Jean Auburtin, he explained: “For me, I’m in tanks up to my neck.” In this immediate pre-war period, for him everything seemed to boil down to psychological phenomena of jealousy and envy on the one hand, and pride and selfishness on the other.

Before being a social thinker, General de Gaulle was always a philosopher of sovereignty, independence and freedom. But his social thought would emerge in London, during the war years, after the long silence of the twenties and thirties. His first speech, in which the social question appeared, was given in Albert Hall, on November 15, 1941, a month and a half after the Labor Code brought in by the Vichy regime on October 4, 1941. The speech at Oxford, on November 25, 1941, is also essential in understanding the thought of de Gaulle, because it evokes the role of the machine, the advent of the masses and the collective conformism which undermines individual freedoms. The economy is certainly important, but it is only a means to the service of higher ends. Therefore, any system where the economy is an end in itself, whether it be savage capitalism or totalitarian collectivism, is sidelined. Gaullism postulates the primacy of man over economics, technology and any doctrinaire system.

While he agreed to parties, unions and notables, and conceded to them the day-to-day management of politics, de Gaulle denied anyone the right to question the major options of his national and international policy. Contemptuous of “the chattering, maliciously gossiping, and babbling class,” severe critic of the inconsistency, ineffectiveness and carelessness of the Left, de Gaulle pitilessly denounced the stupidity and immobility of the Right.

But his most acerbic criticisms were addressed to the privileged classes, to the money and knowledge bourgeoisie, that were all too often considered jaded, unhealthy and gangrenous, and to its spokespersons from the journalistic fauna. “The people have healthy reflexes. The people feel or are have the interest of the country. They are not often wrong. In reality, there are two bourgeoisies. The money bourgeoisie, those who read Le Figaro, and the intellectual bourgeoisie, who read Le Monde. The two make quite the pair. They get along to share power. I don’t care that your journalists are against me. It would actually annoy me if they weren’t. I would be sorry. Do you hear me! The day when Le Figaro and L’Immonde [the foul – a play on the name of the French daily, Le Monde. Trans.] supported me, I would consider it a national disaster.”

Firmly attached to the Colbertist tradition, for him, nothing important could be done in France, if not by the state which must take the initiative. The state has the means, it must be used. “The aim is not to dry up the sources of foreign capital,” declared de Gaulle, “but to prevent French industry from falling into foreign hands. We must prevent foreign management from taking over our industries. We can’t rely on the selflessness or patriotism of the CEOs and their families, can we? It is too convenient for foreign capital to buy them, to pay sons and sons-in-law in good dollars… I don’t care about BP, Shell and the Anglo-Saxons and their multinationals!… This is just one of the many cases where the power of the so-called multinationals, which are in reality huge Anglo-Saxon machines, has crushed us, the French in particular, and the Europeans in general… If the state does not take matters into its own hands, we get screwed.”

In the twentieth-century, the state had the duty to stimulate a shared economy and to establish the participation of workers in the life of the company. To avoid the situation of permanent antagonism between bosses and workers, capital-labor association and participation (a theme particularly dear to de Gaulle) needed to be implemented at three levels. First and foremost, profit-sharing in the company. Second, participation in capital appreciation to make workers co-owners.

Finally, the associative management of companies by both executives and all staff. Wage earning, in other words, the employment of one man by another, “should not be the definitive basis of the French economy, or of French society,” said de Gaulle, “and for two reasons: first of all, human reasons, that is, reasons of social justice; then for economic reasons, since the system no longer makes it possible to give those who produce the passion and the will to produce and create.”

It is quite obvious that this type of relationship cannot fit into either liberalism or Marxism. Thus, it clearly appears that the Gaullian position, since it repudiates on the one hand, collectivist totalitarianism, and on the other hand, laissez-faire and the law of the jungle, can only be based on the principles of the shared economy.

De Gaulle was not anti-European, as his adversaries, who are subservient to the United States and NATO, say he was. He wanted Europe, but not just any Europe. He even had the deepest awareness of what it represents: the historical link between peoples, beyond their discords, their conflicts; the extraordinary contributions that each of them has made to the world heritage of thought, science and art. In his Memoirs, he does not hesitate to emphasize “the Christian origin” and the exceptional character of the heritage of Europeans.

His idea of Europe and nation-states was radically different from that of his social-democratic or Christian-democratic opponents, such as Alcide De Gasperi, Paul-Henri Spaak, Robert Schuman or Jean Monnet. While they dreamt of a federation, he wished for a confederation. While their perspective was the absorption of Europe into a larger community, into the Atlantic community, de Gaulle wanted a continental, independent and sovereign whole: “Each people is different from the others, incomparable, unalterable,” he stated. “They must remain themselves, as their history and their culture have made them, with their memories, their beliefs, their legends, their faith, their will to build their future. If you want nations to unite, don’t try to integrate them like how you integrate chestnuts into chestnut puree. You have to respect personality. We have to bring them together, teach them to live together, bring their legitimate rulers together, and one day, to confederate, that is to say, to pool certain skills, while remaining independent for everything else. This is how we will make Europe. We will not do it otherwise.”

The idea of a “Europe from the Atlantic to the Urals,” of a Europe liberated from the American-Soviet condominium, of a “new European order,” of real independence for all of Europe from the outside world, is fundamental in the Gaullian vision of the future multipolar world.

Without the obsession for emancipating Europe from its position as a satellite of the United States, one cannot understand de Gaulle’s foreign policy, nor his exit from the NATO system, (“a simple instrument of American command”), neither his hostility to the “exorbitant privilege” of the dollar playing the role of international reserve, nor his repeated refusal to admit the candidature of Great Britain in the Common Market, nor his obstinate fight for the common external tariff and the preference community. “If Westerners of the Old World remain subordinate to the New,” said de Gaulle, “Europe will never be European and neither will it be able to bring together its two halves.”

“Our policy,” he confided to his minister and spokesperson, Alain Peyrefitte, “I ask you to make it clear: it is to achieve the union of Europe. If I wanted to reconcile France and Germany, it is for a very practical reason, it is because reconciliation is the foundation of all European policy. But which Europe? It must be truly European. If it is not the Europe of the peoples, if it is entrusted to a few more or less integrated technocratic organizations, it will be a story for professionals, limited and without a future. And it is the Americans who will take advantage of this to impose their hegemony. Europe must be independent.”

For de Gaulle, it was clear that Western Europe must have strong allies to face the dangers of communism. But in his eyes, there was also a second threat, just as formidable – American hegemonism.

The construction of Europe therefore needed to be done without breaking with the Americans, but independently of them. Further clarifying his thinking, de Gaulle added “You can only build Europe if there is a European ambition, if Europeans want to exist for themselves. Likewise, a nation, in order to exist as a nation, must first be aware of what differentiates it from others and must be able to assume its destiny. National feeling has always been affirmed in the face of other nations: a European national feeling can only be affirmed in the face of the Russians and the Americans.”

What he criticized the Anglo-Saxons for is wanting to build a Europe without borders, a Europe of multinationals, placed under the final tutelage of America, a Europe where each country loses its soul. Realistically, he continued: “America, like it or not, has today become a business of global hegemony… The expansion of the Americans since WWII has become irresistible. This is precisely why we must resist it.” And again: “The Europeans will not have regained their dignity as long as they continue to rush to Washington to take their orders. We can live like a satellite, like an instrument, like an extension of America. There is a school that dreams only of that. It would simplify things a lot. That would free from national responsibilities those who are not able to carry them… It’s a design. It’s not mine. It is not that of France… We need to pursue a policy which is that of France… Our duty is not to disappear. It has happened that we have been momentarily erased; we never resigned ourselves to it… The policies of the Soviet Union and that of the United States will both end in failure. The European world, mediocre though it has been, is not ready to accept Soviet occupation indefinitely on the one hand and American hegemony on the other. It can’t go on forever. The future is the reappearance of nations.”

Firmly attached to the French nation, whatever its components, de Gaulle would have been indignant against those who today do not give preference to the French. “It is in the preamble to the 1958 Constitution,” he recalled. “The French people solemnly proclaim their attachment to human rights and the principle of national sovereignty… Article 1: equality before the law is guaranteed to all citizens. We don’t talk about others. So, there is primacy of the citizen whatever the source.” And again: “Was it not up to us, former colonists, who allowed the former colonized to give preference to the population, to demand today that preference be given to the French in their own country? Refusing causes racism.”

Love de Gaulle or hate him, but in terms of the General himself, we can only feel disgust and contempt for his successor-impostors who have mythologized him the better to betray him.

Arnaud Imatz, a Basque-French political scientist and historian, holds a State Doctorate (DrE) in political science and is a correspondent-member of the Royal Academy of History (Spain), and a former international civil servant at OECD. He is a specialist in the Spanish Civil War, European populism, and the political struggles of the Right and the Left – all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles on the political thought of the founder and theoretician of the Falange, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as well as the Liberal philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset, and the Catholic traditionalist, Juan Donoso Cortés. Translated from the French by N. Dass.

The image shows a mural of Charles de Gaulle before the Saint Mandé tow-hall, by Bernard Romain.