Understanding the Spanish Civil War means knowing that it was “a mixture of vanity and sacrifice, clownery and heroism,” wrote Arthur Koestler in his autobiography, The Invisible Writing. It was a fratricidal war between fellow citizens and friends, between parents and children, between brothers and sisters. The examples speak for themselves. Thus, the brothers Manuel and Antonio Machado, whose literary output had previously been joint, clashed over ideological reasons – one was in the anti-communist, pro-national camp, the other was a member of the Association of Friends of the Soviet Union and sympathized with the United Socialist Youth.

Buenaventura Durruti, the anarchist leader who died under obscure circumstances, most likely a victim of the Communists, opposed his younger brother Marciano Pedro Durruti, who was a Falangist. Constancia de la Mora Maura, aristocrat and member of the Communist Party, whose husband, Ignacio Hidalgo de Cisneros, was the commander-in-chief of the Republican Air Force, clashed with her sister, Marichu de la Mora, writer, journalist, personal friend of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, and one of the founders of the Women’s Section. It was a total war, in fact, between left-wing totalitarians and right-wing authoritarians.

In the Spain of 1936, there were no more democrats. Hatred and bigotry infected both sides. But respect for others, nobility and generosity sometimes transcended divisions.

Here is the moving testimony of José Ataz, a young “hijo de rojo” (Son of the Reds), who experienced the horrors of a fratricidal war and the terrible privations of the immediate post-war period. His is a very human true story, which alone allows us to understand the complexity of this terrible historical event, which was commemorated in 2006. A story that does not judge, that does not say good or bad, that does not pursue demonization, or discriminated between the pure and the impure – but which contributes honestly and modestly to the search for truth and sincere reconciliation.

In August 1936, José, an eight-year-old boy, witnessed an excruciating scene that marked him forever. His father, Joaquin Ataz Hernandez, Secretary of the UGT railwaymen’s union in Murcia, and provincial leader of the PSOE, had just been appointed by his party to sit on the Special People’s Court of Murcia. The People’s Courts were created at the end of August, 1936, by decree of the government. They were composed of seventeen judges, fourteen of whom were appointed by the parties and trade unions of the Popular Front (left-wing liberal-Jacobins, socialists, communists, Trotskyists and anarchists). On September 11, the People’s Court of Murcia sat for the first time.

Of the twenty-seven people tried that day, ten were sentenced to death, eight to life imprisonment; the others were given heavy prison sentences. Among those sentenced to death were the parish priest, Don Sotero Gonzalez Lerma and the Murcia’s provincial chief of the Falange, Federico Servet Clemencín.

Joaquin Ataz Hernandez voted the death penalty for the young Falangist leader. The order he received from his party could not be argued – the “fascist” had to be executed. “My father had known Federico since he was a child,” says José. “They were not friends, but they liked each other and respected each other. Also, just after the sentence, he approached to say: “Federico, I really regret …” but before he could add another word, Federico interrupted him: “Don’t worry about it, I would have done the same with you, give me a cigarette!”

Two days later, very early, on the morning of Sunday September 13, several trucks full of men and women awoke José. It was rumored that the Government wanted to pardon the condemned, and the crowd in turmoil, demanded “justice.” In a state of dismay, the civilian governor ordered the executions be hastily carried. The furious crowd soon entered the prison courtyard and came upon the corpses.

The bodies were desecrated and mutilated mercilessly. In the middle of the morning, little José, who played in the street, saw and heard the vociferous populace. Overexcited men and women seemed to be pulling a strange load with ropes. With all the curiosity and agility of his age, José got close – and he was seized with dread. In front of him law a bloodied body, which had been turned into shreds for being dragged along the pavement. None of the viragos present prevented him from witnessing the scene. No one came to his aid when he vomited and fell unconscious to the ground.

As soon as he recovered, he ran to his parents’ house crying. His mother consoled him. How can such acts of savagery be even tolerated, she asked her husband in disgust? The father could not answer as his shame was great. At this moment, they did not know that it was the body of the parish priest, Don Sotero Gonzalez Lerma, who had been horribly mutilated, dragged through the streets and hanged from a lamppost of the façade of his church, where a militiaman triumphantly cut off his ear and demanded that a tavern-keeper serve it well grilled with a glass of wine.

Soon thereafter, Joaquin Ataz Hernandez resigned from the People’s Court. At the end of April 1937, he was appointed head of the Prison Corps, and not long after he became head of the Totana labor camp (Murcia), where nearly two-thousand political prisoners (those sentenced to life imprisonment, or thirty years’ imprisonment) served their sentences in very difficult but nevertheless humane conditions. On April 1, 1939, bells rang and firecrackers burst. José and his two brothers saw their father, unflappable, calmly combing his hair, while their mother sobbed: “Don’t worry the children, the war is over, but I have to leave for a few days on the road.” The few days would turn into years.

Under the seal of secrecy, José learned from his mother that his father had managed to embark on a journey to Mexico. To survive, the little boy had to work. He was, by turns, a kitchen boy, and apprentice carpenter, storekeeper and baker. He finally and enthusiastically returned to school. In class, all children knew the political background of each family, but no one said a word.

In October, 1942, during a civics course, José by chance heard his teacher explain that José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the leader of the Falange, and sentenced to death by a People’s Court and executed in November 1936, “considered that the birth of socialism was right.” These words, in the mouth of an adversary, seemed so unusual that José immersed himself in reading the Complete Works of the founder of the Falange. When he finished, he was both excited and convinced.

José now faced a serious internal crisis. Was he betraying the ideals for which his father fought so honestly throughout his life? Luckily, José was able to discuss everything with his father. For some time now, he had known that his father was not exiled to Mexico but was living in hiding with his own parents.

Without further hesitation, José visited him and made him read the speeches and testament of José Antonio. “I was frankly asking him about the problem in my own conscience,” he said, “and he answered me with all the generosity and nobility I expected of him: “Listen, my son, I have no moral authority to advise you in a realm, where I have done things, rightly or wrongly, for which you must suffer all kinds of privations and know hunger. A single person can follow his ideals to the very end, without limits. But a man who has a wife and children has no right to compromise the survival of his family. Do what your heart dictates, but always make sure you don’t compromise others by your decisions. Hear me good, Pepe, always act with honesty and consistency!”

His conscience finally free, and “having obtained the permission of the only man whose authority I recognized over my own person,” added José, “I joined the Youth Front and I could finally wear my first blueshirt.” Head of Century of the Youth Front, he then began studying law and was appointed head of the SEU (official student union) of the university district of Murcia.

At the end of 1948, José’s father, who had lived cloistered for more than nine years, decided to leave his hiding place. He took the first train to Madrid. Thanks to the grateful friendship of people he helped during the war, he found work. For two and a half years, he was employed in an electric lamp shop in the Puerta del Sol, then in a canning factory, without ever being worried. But, one day in October 1951, his son José, then a candidate senior officer cadet in a regiment of Seville, learns that his father had been arrested, a victim of the denunciation of an employee dismissed for embezzlement.

José had to do everything possible to help his father. In the spring of 1952, a War Council was convened. Many witnesses took the stand. All pointed out that the conduct of the accused during the war was beyond reproach. Among them were some who even owed him their lives, as was the case with the professor of commercial law at the University of Murcia, Salvador Martinez-Moya, who was undersecretary of justice in the government of the radical Alejandro Lerroux. Unyielding, the prosecutor asked for the death penalty. The jury withdrew and deliberated for many long minutes. When they reconvened, the president pronounced the sentence: The accused was sentenced to thirty-years in prison – but because of the various remissions of sentence and pardons granted, he was immediately released.

After completing his studies, José joined the law firm of Don Salvador Martinez-Moya, who was a key witness in his father’s trial. As chance would have it, he was joined in the firm by the eldest son of Federico Servet, the provincial leader of the Falange whose death his own father had voted for. “I got along very well with Ramon,” José wrote. “We never talked about our fathers, but we knew the tragic relationship they had had. Ramon was very disappointed to see that Spain was moving away from what his father had dreamed of. Finally, he went to Mexico and we lost touch with each other.”

Intelligent and hard-working, José held various positions in the administration. It was the beginning of a meteoric rise. In 1964, the Under-Secretary of State for Finance called on him. Ten years later, he was Deputy Director General of the Department of Finance.

In 2006, at the age of eighty, José Ataz Hernandez (1927-2011) wanted to bear witness above all.

Here are his own words: “Neither I nor my brothers (one of whom is now a socialist), have ever had to reconcile with anyone because no one was ever against us. On the contrary, we have experienced in many cases, both discreet and anonymous, generosity and greatness of soul, which would be inconceivable today. An example: at my father’s funeral, Manolo Servet was present. Manolo was a friend of mine from the Youth Front, and my brother Joaquin’s workmate. He was the second son of Federico, the young provincial chief of the Falange of Murcia who had been sentenced to death with the participation of my father. When he approached me to offer his condolences and give me a hug, I had to make a superhuman effort not to start crying…”

[Testimony of José Ataz collected by Arnaud Imatz].

Arnaud Imatz, a Basque-French political scientist and historian, holds a State Doctorate (DrE) in political science and is a correspondent-member of the Royal Academy of History (Spain), and a former international civil servant at OECD. He is a specialist in the Spanish Civil War, European populism, and the political struggles of the Right and the Left – all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles on the political thought of the founder and theoretician of the Falange, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as well as the Liberal philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset, and the Catholic traditionalist, Juan Donoso Cortés.

This article was translated from the original French by N. Dass.

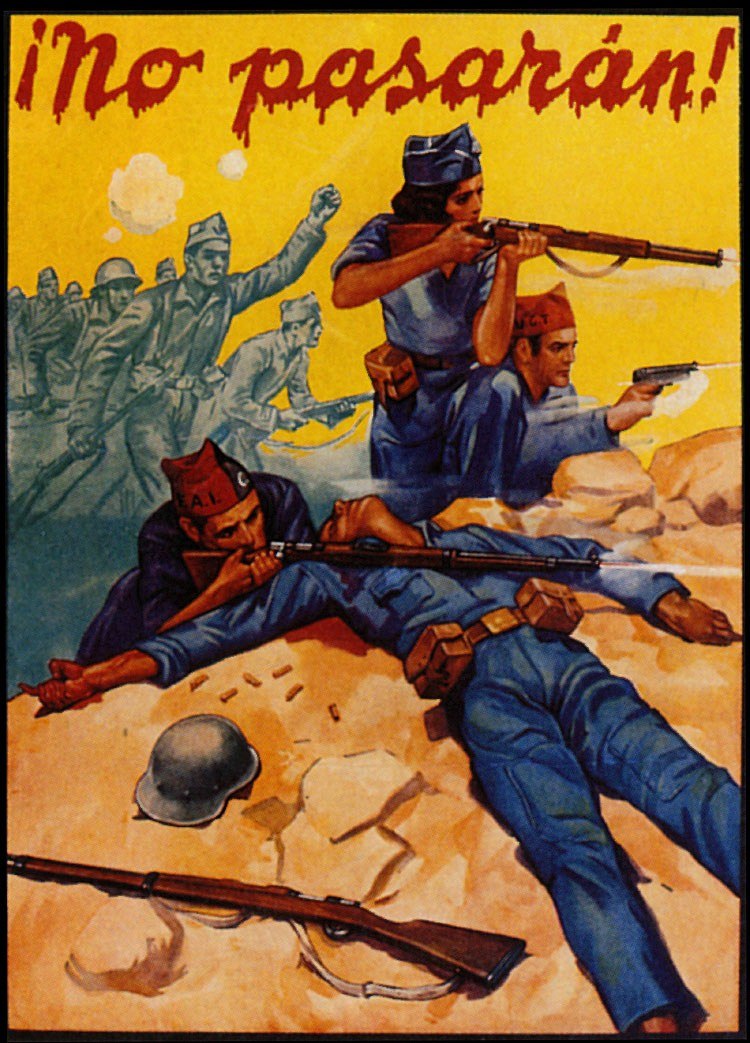

The image shows a poster from the Spanish Civil War, with the famous slogan, “They Will Not Pass!”