Who was responsible for the assassination of Federico García Lorca, during the Spanish Civil War? Thanks to the work of a host of journalists and historians, such as, Marcelle Auclair, Ricardo de la Cierva, Ian Gibson, José Luis Vila San Juan, Luis Hernández del Pozo, Eduardo Molina Fajardo, and Manuel Titos Martínez, to name a few, the answer is well known today.

The historical truth concerning the death of the famous Spanish poet belies partisan interpretations. Despite being an icon of the gay community, Federico was not “a militant of the left,” contrary to the false catchphrase inherited from the propaganda of the Comintern. Protected by Falangist friends, he was assassinated on August 18, 1936, on the orders of Commander Valdés, with the help of deputy Ruiz Alonso (a former typographical worker, Member of Parliament in the district of Granada from 1933 to 1936), two activists of the liberal-conservative right (CEDA).

Federico García Lorca is undoubtedly the best-known poet and playwright of Spanish literature of the 20th-century. Illegally arrested on August 16, 1936, in the midst of a civil war, he was assassinated at the age of 38, on the road from Viznar to Alfarez, near Granada. The decision of Madrid judge, Baltasar Garzón (October 16, 2008), to open nineteen pits, one of which, according to various testimonies, held the poet’s remains, did not fail to rekindle the debates and controversies over the disturbing circumstances of his death. And all the more so, since this controversial decision was accompanied by continual pressure meant to weaken the express will of the Lorca family who had clearly expressed their refusal to exhume the poet’s remains and their desire to respect the eternal rest of the dead. Refusing to accede to the heirs’ request, the National Auditing Judge imposed an emergency exhumation, but “in private,” and allowing the family to be present. To date, however, attempts to exhume the body of the poet, made on the basis of various testimonies collected since 1955, have all proved unsuccessful.

So, what are the well-established facts about the crime on the Viznar road? How are they interpreted? Did Federico García Lorca die because of his sympathies for the Popular Front and his fight against fascism? Is he the symbol or the most famous victim of the intransigence of traditional Spain, or worse, of “the implacable mechanism of extermination set up by Francoist Spain?” Was he instead the play-thing of a centuries-old rivalry between two wealthy families in Andalusia? Was he, on the contrary, an unfortunate scapegoat marked for his declared homosexuality?

According to the most widespread myth, popularized over and over again by the cinema, the press, television and radio, Lorca was “an intellectual of the Popular Front assassinated by the Falange.” It is a legend that has nothing to do with reality, however. The poet’s nephew, secretary of the Foundation that bears his name, Manuel Fernández-Montesinos García-Lorca, objected sternly, “against those who seek to minimize the literary value of Federico… against the politically-motivated insistence on wanting to open the pit where his body rests… against the use of his grave for propaganda purposes.”

Historical truth denies partisan interpretations. Not only were the Falangists not the perpetrators of the crime, but among the Nationals they were the ones doing everything possible to win freedom for the poet. This barbaric crime is actually the result of a Machiavellian maneuver orchestrated by members of the Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Rights (CEDA), the main Conservative and Liberal party of the Second Spanish Republic, who sought to gain the sympathy of the military and to discredit the José-Antonian Falange, by demonstrating that some of the Falangist leaders were protecting and hiding “Reds” in their own homes.

Can Lorca be considered a leftist activist? Nothing is less sure. All those who really knew him have testified that politics was not his main concern. Lorca was above all a writer who was at the same time elitist, refined, baroque, avant-garde and popular. In him converged tradition and modernity, liberal secularized culture and traditional religiosity, particularism and universalism. Born into a wealthy family, his sensitivity led him to defend the poorest, the peasants and the gypsies, in the name of social justice. But he was by no means a revolutionary. He used to say, “I have more sorrow for a man who wants to access knowledge and who does not have the possibility than for any man who is hungry.”

Lorca refused, in principle, to participate in a political act, even if it had a cultural connotation. He repeatedly expressed irritation when his name was used for political gain. Asked about his political preferences, he replied that he felt “Catholic, communist, anarchist, traditionalist and monarchist.” His detachment from politics allowed him to maintain friendly relations with writers of very different convictions – Communists, like Rafael Alberti; Socialists, like Fernándo de los Rios; or Falangists, like Agustin de Foxá, Edgar Neville, or Felipe Ximenez de Sandoval.

Gabriel Celaya, Basque poet and Communist activist, attested to this. He even told the following (disputed) anecdote. At the end of February 1935, Lorca and Celaya met at the Madrid Casablanca cabaret. As soon as he arrived, Celaya was surprised to see Lorca in the company of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, the founder of the Falange. “Hey! Come here!” cried Lorca. “I will introduce José Antonio to you. You’ll see, he’s a very nice guy.” The three men spent the evening together over a good bottle of whiskey (see Gabriel Celaya, “Un recuerdo de Federico García Lorca”, Realidad: revista de cultura y política, Rome, April 9, 1968). Gabriel Celaya also reported a second anecdote. The following year, March 8, 1936, he found Lorca at the Biarritz Hotel in San Sebastian. He was really surprised to find Lorca this time in the company of the architect, José Maria Aizpurua, founder of the Falange of the Basque province of Guipúzcoa. This meeting came in the aftermath of the February elections, which had brought the Popular Front to power, and feelings were particularly heated. Celaya refused to shake hands with Aizpurua. But once the Falangist left the room, Lorca reproached Celaya sharply for dampening the mood. Mischievously, he confided to him, with a playful air: “Aizpurua is a good guy, who admires my poems. Besides, he’s like José Antonio. He’s another good guy. Do you know that every Friday we have dinner together?”

The main contact with the Falangist movement, for Lorca, was Luis Rosales, a young poet from Granada, who was a student of philosophy and the law, and who was also editor of the Madrid magazine, El Gallo. Rosales would play a key role in the last days of Lorca’s life.

During dinner with Pablo Neruda, the Chilean poet, on 12 July 1936, Lorca declared his intention to leave Madrid to take “shelter from lightning.” The next day, he confided to his Falangist friend, Edgar Neville: “I am leaving because they want me to get into politics here, when I don’t hear anything and I don’t want to know anything. I’m everyone’s friend, and I just want everyone to be able to work and to eat.”

On July 15, the poet arrived in Granada safe-and-sound, and lived happily on the family farm, Huerta de San Vicente, with his parents, his sister Concha, his two nephews, and the nurse Angelina. The turmoil of the Civil War, however, quickly caught up with him. On July 18, 1936, when the first reports of the military uprising reached Madrid, the Far-Left published in the press a cruel caricature of Lorca. He was shown dressed for first communion, and the unsavory caption below the drawing was an unambiguous attack: “García Lorca: cute child, pride of his mother.” More seriously, on the radio, the Communist poet, Rafael Alberti, recited insulting verses about insurgent soldiers which he attributed wrongly to Lorca. The prestigious liberal writer, Ramón Pérez de Ayala, accused Alberti of knowingly trying to have his friend killed. The poet’s sister telephoned Alberti to beg him not to endanger her brother’s life any further.

The uprising reached Granada on July 20. The insurgent soldiers, commanded by young officers, and supported by several groups of civilians, activists from the right-wing parties and the Falange, won in three days. In the city, isolated and surrounded by the forces of the Popular Front, things were extremely volatile. Reports of the massacres perpetrated by left-wing militiamen in Malaga soon triggered terrible repression. All over the Peninsula, massacre was met with massacre, repression with repression.

In Granada, Commander José Valdés Guzmán assumed the power of Civil Governor. He appointed his men to key positions and constituted a department responsible for repression. Valdés was a soldier who claimed to be a Falangist, but who in fact came from the Spanish Confederation of Autonomous Rights (CEDA), a Liberal-Conservative party. On the eve of the February 1936 elections, he was one of those responsible for training the candidates of this party, which was the bane of the Falange. With him were the chief of police, Julio Romero Funes, the former member of the CEDA, Ramón Ruiz Alonso, a heterogeneous group of right-wing activists, and lastly another group comprised of neo-Falangists, or “New Shirts” (as opposed to activists before the outbreak of the Civil War, who were called the “Old Shirts”).

Across Spain, the Falange – over 60% of whose leaders had been murdered or detained – was literally overwhelmed by new recruits. José Antonio’s Falangist movement had no more than 30,000 to 40,000 members on the eve of the conflict. It suddenly saw its membership increase to 200,000 and then to 500,000 members. These New Shirts, under the command of ad-hoc executives, appointed in the absence of any real leadership, knew nothing about national trade unionism and were largely uninterested in social concerns.

In the city of Granada alone, the few dozen Old Shirts, or José-Antonian Falangists, were overwhelmed by more than a thousand New Shirts from right-wing parties. To lead them, Commander Valdés appointed a Captain of the Assault Guard, a sort of Republican Guard, Manuel Rojas Feijespan. Not long after, Valdés came into conflict with Patricio González de Canales, the leader of the Old Shirts, who had been appointed directly by José Antonio, and who was a true lay saint. Canales stubbornly refused to allow his men to participate in the summary detentions and executions. Anxious to get rid of him as quickly as possible, Valdés, in agreement with General Queipo de Llanos, requisitioned an airplane which, after having flown from Seville to Granada, forcibly took away the stubborn Falangist official.

As early as July 20, Lorca had learned of the arrest of his brother-in-law, Manuel Fernández Montesinos, Socialist mayor of Granada. Thereafter, the atmosphere was heavy and tense at the farm in San Vicente. On August 5, Captain Rojas, leading a group of Neo-Falangists, searched the Lorca family home. Rojas claimed to be looking for the farm manager’s brother. Blows and insults rained down. Lorca was beaten, called a “fag,” thrown down the stairs. Finally, growing tired, the militiamen left the place.

In the evening, Lorca, worried about his life, called his friend, Luis Rosales, on the phone and asked for his protection. Professor of literature at the university, Rosales was about to join the front as a Falangist volunteer. He immediately hurried to the farm in San Vicente. After a quick meeting, it was decided that Lorca would stay with his friend, in the center of the city, three hundred meters from the seat of the civil governor, where Commander Valdés resided. As soon as Lorca arrived at the Rosales’ home, Luis’s older brothers, Miguel and Pepe – two early Falangists – and their parents, welcomed the poet with open arms.

It would take Valdés and Ruíz Alonso eleven days to discover this hiding place. On August 16, Lorca’s sister Concha, whose husband was arrested on July 20, confessed, frightened into admission by the threat of having her father taken hostage. For Valdés and Ruiz Alonso, this was too good a windfall. They would also finally be able to get rid of the Rosales and the group of Old Shirts that were openly hostile to them.

The same day, Ruiz Alonso, with an arrest warrant and accompanied by two sections of CEDA militiamen, arrived at the Rosales’ home. In the absence of the three brothers and their father, he was received by Mrs. Rosales. Ruiz Alonso was reassuring. His attitude was so sweet, in fact, that the unlucky Lorca was convinced that nothing would happen to him. Cautious, Mrs. Rosales left Ruiz Alonso at the house, while she urgently went to fetch her son at the headquarters of the Falange. Miguel ran in haste to intervene, but in vain. Lorca had already been taken by force, searched and imprisoned.

That evening, Luis and Pepe Rosales, just returned from the front, decided to act, with the support of a dozen Falangists. Outraged, they all went to the main office of the civil governor, intent on having their friend released. At the entrance, Pepe jostled with the guards who blocked the way. But he got into the office of the civil governor and harshly recriminated Ruiz Alonso and Commander Valdés. The altercation grew extremely violent, and Pepe took out his revolver. But the odds being one against five, the determination of the small group of Falangists was not enough. Pepe Rosales could only obtain permission to see the prisoner.

On the 17th, Pepe again stood in front of Valdés. This time he had in his possession an order to release Lorca, which was signed by the military governor, Colonel Antonio Gómez Espinosa. But nothing helped. Valdés did not get upset, replying that he regretted that the prisoner was no longer here. It was a lie believed by Pepe Rosales, for Lorca was still there for quite a few hours more.

In the early morning of August 18, Lorca was secretly being transferred to the former children’s home at Colonia, which had recently been converted into a place of detention. But along the way, on the road to Alfaraz, he was summarily executed, along with two unfortunate companions, the schoolmaster, Dióscoro Galindo and the banderillero, Francisco Galadi, at 4.45 AM, at the foot of the olive trees of the Viznar ravine.

For years, Commander Valdés, the principal person responsible for Lorca’s death, denied any involvement in the affair. But since 1983, thanks to the research of the journalist from Granada, Eduardo Molina Fajardo, the original statement of the Rosales brothers has been found and the direct responsibility of Commander Valdés established.

The execution of Lorca was indeed ordered by Valdés, with the approval of General Queipo de Llano. In the aftermath of this barbaric crime, Luis Rosales was also imprisoned. He avoided being shot thanks to the substantial fine paid by his family and, above all, thanks to the unexpected arrival in Granada of one of the most prestigious Falangist leaders, Dr. Narciso Perales.

Among the most faithful to José Antonio, Perales clashed with Valdés the moment he arrived. He would testify much later that during their dispute, Valdés cynically confessed to him: “Listen. For me, in this whole business of National Unionism, what is National seems good to me, but what is Unionism makes me sick to my stomach.” Curiously, Valdés, who always wears the Falangist blue shirt in films and television series, never actually wore it in the photos of the time, which were published notably in the newspaper Ideal, between July 1936 and July 1937.

After the creation of the new Traditionalist Falange of Franco, born of the imposed merger of the original Falange and the various right-wing parties, as well as the death sentence given to the second national chief of the Falange, Manuel Hedilla, by the Franco authorities, in April 1937, Dr. Narciso Perales became a dissident and went underground. As for Luis Rosales, after having collaborated in numerous Falangist literary reviews, during the 1940s and 1950s, he distanced himself from the regime.

In March 1937, shortly before the disappearance of José Antonio’s Falange, two magazines expressly condemned the assassination of Lorca by way of the Falangist, Francisco de Villena of Zaragoza. A beautiful elegy, in homage to Lorca, was published by him in the daily Amanecer, then in the weekly Antorcha. Again, on March 11, 1937, Luis Hurtado Álvarez published an article in the Falangist newspaper of San Sebastian, Unidad, in which the first words were unequivocal: “The best poet in imperial Spain was murdered.” Also, in 1937, the Sevillian poet, Joaquín Romero Murube, also close to Falangist circles, dedicated his collection of poems Siete romance to Lorca. (Murube, who was director of the Alcazar in Seville, at the end of the Civil War, also hid another famous friend in the royal palace – the Communist poet and playwright, former volunteer of the Fifth Regiment, Miguel Hernández. In January 1940, during Hernández’s trial, after his arrest, Murube interceded on his behalf, with the help of a small group of Falangist writers and poets, including José María de Cossio, Dionisio Ridruejo, Rafael Sánchez Mazas, Eduardo Llosent and Laín Entralgo. They had the death penalty commuted to 30 years’ imprisonment. But Miguel Hernández died of tuberculosis in prison, in 1942). Finally, to cite just one more example, in 1939, the Falangist poet, José María Castroviejo, also dedicated a poem to Federico García Lorca, which is included in his collection, Altura.

After the war, when in Francoist Spain no one dared to officially mention the real circumstances of the poet’s assassination, Falangists who were friends of José Antonio did not hesitate to publicly affirm that “Lorca was José Antonio ‘s favorite poet.” In the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, the youth magazines of the Youth Front and the Women’s Section, directed by Pilar Primo de Rivera, regularly published poems by Lorca. In 1952, the traveling theaters of the Women’s Section presented the Zapatera prodigiosa.

Many years later, in 2012, collector and art critic, Juan Ramirez de Lucas, broke his long silence by talking about his homosexual relationship with Lorca. It was in 1936; he was 19 years old. (He probably received the last letter written by the Andalusian poet, dated July 18, 1936). Since this revelation, the enigmatic inspirer of the famous Sonetos de amor oscuro is finally known. Author of several books, defender of Valle de los Caidos (the work of architect, Diego Mendez), Juan Ramirez de Lucas, was the great love of Lorca. At the age of twenty-five, he joined the 3rd Battery of the Azul Division Artillery Regiment to fight Communism on the Eastern Front. Subsequently, back in Spain, he joined the editorial staff of the ABC newspaper, on the recommendation of Luis Rosales, before becoming a specialist in popular art and an expert in architectural criticism.

History, as we know, is always more subtle and more complex than ideologists suggest. Thanks to the efforts of some serious historians, the false catchphrase of Federico García Lorca as a “leftist intellectual murdered by the Falange,” which is so much used by the propagandists of the Comintern, will eventually die out and historical truth will prevail.

Arnaud Imatz, a Basque-French political scientist and historian, holds a State Doctorate (DrE) in political science and is a correspondent-member of the Royal Academy of History (Spain), and a former international civil servant at OECD. He is a specialist in the Spanish Civil War, European populism, and the political struggles of the Right and the Left – all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles on the political thought of the founder and theoretician of the Falange, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as well as the Liberal philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset, and the Catholic traditionalist, Juan Donoso Cortés.

This article was translated from the French by N. Dass.

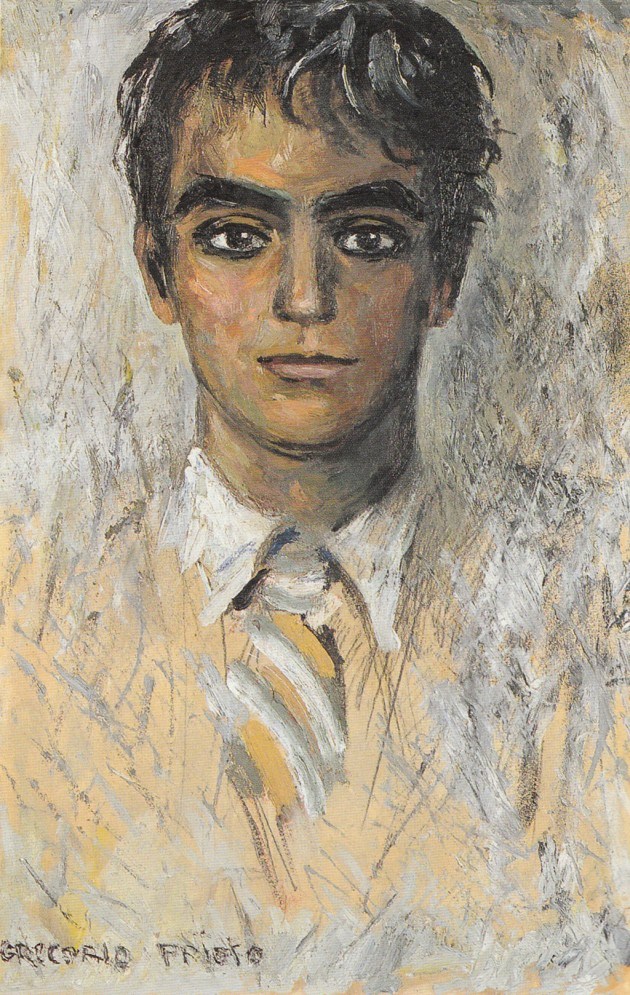

The photo shows a portrait of Lorca by Gregorio Prieto, painted ca. 1937.