This month we are so very pleased to publish the English version of an interview with Dr. Arnaud Imatz, the renowned French historian, who has published over a dozen books and numerous articles in both European and American journals and magazines. Dr. Imatz has contributed several times to the Postil. Here, Dr. Imtaz is in conversation with La Tribuna del Pais Vasco in regards to his new book, Vascos y Navarros (Basques and Navarrese).

La Tribuna (LT): How did the idea of writing the book, Vascos y Navarros, come about?

Arnaud Imatz (AI): I started by writing a chronological article in French and was surprised to see it published in a tourist guide in which they did not even mention my name. As a result, I decided to considerably revise and expand that article. More than anything, it is a small tribute to my ancestors. They were Basques, Navarrese and Béarnais. They were fishermen, bakers, vintners, public works contractors, military men, carpenters, tobacco growers, booksellers, restaurant owners and hoteliers, located for the most part in Hendaye.

I was born in Bayonne, but after a few months of life I was already going with my mother to the beach at Hendaye, La Pointe, right by Fuenterrabía. A beautiful place, now gone, having been replaced by the beautiful but conventional marina, the marina of Sokoburu. With my wife, my son and my two daughters, I first in Paris and then for twenty years in Madrid. I have unforgettable memories of Madrid and close friends (even a true “spiritual son”). But I spent most of my time – more than forty years – in the Basque Country, an exceptional place in the world.

Of course, my Galician, Breton, Andalusian or Corsican friends may disagree. This is normal. My children and grandchildren, who live further north, and my wife, born in the Ile-de-France (although of partly Biscayan descent), sometimes make fun of my excessive attachment to the land. But what difference does it make! I also had my doubts and reacted with skepticism when in the distant 1980s a Basque friend, a professor of Law, who had been a member of the tribunal that examined my doctoral thesis, answered my questions: “How about La Reunion? La Martinique?” etc.: “Well, well, but you know that when you see Biriatu ….” He didn’t even bother to finish his sentence. Now I know he was right.

LT: So your family has deep roots in the Basque Country?

AI: Yes, indeed. My surname, Imatz or Imaz, meaning “wicker,” “of wicker,” “pasture,” or “reed,” is found, above all, in the Basque Autonomous Community, but it is also present, although less frequently, in Navarre and the French Basque Country. On my mother’s side of the family, there are a good number of Basque surnames. Most were born and lived in Hendaye. Some moved away, went to work in different cities in France or Spain (Madrid, Palencia or Andalusia), even in America. But sooner or later almost all of them returned to their native town in the French Basque Country.

My maternal grandfather was Basque, Carlist and of course Catholic. He kept a beret his whole life which was given to his family by Don Carlos. He worked in hotels in Guayaquil and London and later in the María Cristina de San Sebastián, when it opened in 1912. During the First World War, he was a gunner in the Battle of Verdun. Once demobilized, he returned to Hendaye to take over his parents’ hotel. He spoke Basque and French, but also Spanish, like most of the members of my family at that time; and by the way, they were very closely connected with Spain and the Spanish.

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, my great-grandfather had a brother, who was parish priest in Biriatu. He was dedicated to his priesthood, but he also liked to play pelota. Yes! And always wearing his cassock. He became very involved in the defense and safeguarding of the Basque language and culture. Such were the famous French-Basque priests of yesteryear.

My great-aunt used to play the piano and she taught me, among other things, the Oriamendi and the Hymn of San Marcial. From her house, located on the banks of the Bidasoa, she could see the Alarde de Irún and at night hear, although very rarely, the whispers of the smugglers. My great-aunt and great-grandmother (a strong widow who had been the director of the Hendaye Casino in the 1920s) told me many memories of our border family.

LT: Can you tell us about some of these memories?

AI: Some anecdotes. A few months before he died, my Carlist grandfather, naturally in favor of the national side, negotiated with Commander Julián Troncoso, a friend of his, for the exchange of a friend from the Republican side, Pepita Arrocena. As a result of the attempted Socialist Revolution, in 1934, Pepita had crossed the border with her driver and with the socialist leader, Indalecio Prieto, hidden in the trunk of her car.

Also, French friends of my grandfather participated in the unsuccessful assault on the Republican submarine C2, which was anchored in the port of Brest. I must say that during the Civil War, many foreign correspondents used to stay at my grandparents’ hotel.

At the end of the war, my grandmother, now a widow, was close friends with the wife of Marshal Pétain, French ambassador to Spain. But two years later, being in the so-called “forbidden” area, in the middle of the Nazi occupation, and despite her friendship with Annie Pétain, the “Marshal,” my grandmother sympathized with the Gaullists and participated in anti-German Resistance. She was in contact with the ORA (Organization de Résistance de l’Armée) of the Basque Country, along with her friend, Dr. Alberto Anguera Angles, from Irune, who was in charge of routing messages of those escaping from France.

The other branch of my family, the paternal one, was Béarnaise, from Pau and Orthez. My paternal grandfather was a Catholic Republican, a non-commissioned officer who was one of the most decorated soldiers of the First World War. Handicapped by the war, he settled in Hendaye in 1919, with his wife and four children as a tobacconist and bookseller. His son, my father, was born in Hendaye six months later.

My father was a great athlete, who was four times French pelota champion in the 1930s and 1940s, with the long bat (pala larga) and in the plaza libre (court). My paternal family was then divided between the stalwarts of Marshal Pétain (my grandfather), and the supporters of Charles de Gaulle (his four sons, among whom were my father and my godfather). The oldest of my grandfather’s sons was seriously injured at Dunkirk.

All these family memories made me understand very early that history is not Manichean, that it is always made of light and dark, that there are no absolute good and bad, that there are no so-called historical or democratic justices as peddled by the traffickers of hatred and resentment, who are miserable political puppets who live to play with fire.

LT: In your opinion, do more things unite or separate Basques and the Navarrese?

AI: To answer in detail it would be necessary to refer to the long history of the medieval Basque counties, the kingdom of Navarre, Spain, the Hispanic Empire and the French nation-state. These are topics that I address, albeit briefly, in the historical summary given in my book. I would of course be unable to summarize all these substantial issues in a few words. I concede that personally, despite my nationality, and due to my Spanish-French culture, I sympathize much more with the Hispanic Catholic Empire of Charles V and Philip II than with the Gallican-Catholic French nation-state of Richelieu, Louis XIII, Louis XIV and the Revolutionaries of 1789 and 1792. We already know that the “reason of state” of these French politicians was greatly influenced by Machiavelli and indirectly by the writings and attitude of the Protestants. That said, five, ten or fifteen centuries of common history cannot just be erased, manipulated, or misrepresented.

Now, if in your question you refer essentially to our own time, I will tell you that, paradoxically, there are more and more things that unite the Basques and Navarrese and less that separate them. But, beware! This does not mean that I fall into those independence or separatist dreams. What I think is happening is that both these peoples are losing their specificities and are gradually uniting – but unfortunately into nothingness, in the great meat-grinder of globalism.

Let me explain. At this point, we are all victims of globalization, consumerism, commercialism, demographic decline, multicultural individualism, the decline of religion and the Church and Christianity – all these many plagues that have shown themselves, in the long run, to be much more corrosive and deadly for both the Basques and the Navarrese (and also in general for all the peoples of Europe) than the “forty years of Franco’s dictatorship,” or the “Bourbon centralism of the 19th century,” or “French Jacobin centralism.”

It is true, thank God, that our lands (which have sometimes been marked by savage violence unworthy of human beings) have not endured the horrors of Nazism, or worse still (because of the sheer number of deaths) the monstrosities of Marxist-communist totalitarianism. In this, the radical nationalists are completely blind and are totally wrong as to who the enemy is. Torn apart by the hodgepodge of Marxist internationalism and what Americans call “cultural Marxism,” the radical, Abertzale left has become the perfect ally of hypercapitalism or globalist turbocapitalism. The two, globalists and nationalist-separatists, are tearing apart the best of the Navarrese and Basque values, the deepest roots of both peoples. In the background are two grips of the same vise.

LT: In your opinion, what does Euskara mean for the reality of Basques and Navarrese?

AI: It is an important factor, but not enough to define the entirety of Basque identity and reality. Just as important are ethnicity, demographics, culture, and history. There are Euskaldunak Basques, because they speak the Basque language. There are Euskotarrak Basques because they are ethnically defined as Basques, even though they express themselves in French or Spanish. And there are Basques who are Basque citizens because they reside in the Basque Country and love the Basque Country. In the Autonomous Community of Navarra, which is founded on a long and brilliant history of its own, it is another story: there are Basques who feel Basque and many Navarrese who are not and do not feel Basque.

What the Basque Government does to defend the Basque language seems to me to be quite successful, despite all the cartoonish and meaningless actions that have been taken against the Castilian language or – better said – Spanish, which is one of the two or three most widely spoken languages in the world. We already know that language is not enough. In addition to this, it should not be hidden, the results of the policies in favor of the Basque language are rather negligent. The reality is that there is no nation or country possible without a historical legacy, combined with consent and a will to exist on the part of the people. Nicolas Berdiaev and other famous European authors such as Ortega y Gasset spoke of unity or community of historical destiny. Well, without the harmonious combination of the historical-cultural foundation and the voluntarist or consensual factor, without these two factors, there can be no nation. And that is why there is no longer a true Spanish nation today, as there are no true nationalities or small nations within Spain today.

The same can be said of the rest of Western Europe, whose power is in clear decline, if we compare it to the current great powers. In France, it is very significant that a professional politician like Manuel Valls, who always believes he has an ace up his sleeve, has recently admitted that “French society is gangrenous, fractured by Islamism.” For this very reason, the Catalan authorities and Catalanists, who emphatically declare or hypocritically imply that they prefer North African immigration that does not speak Spanish, considering it more prone to learning Catalan, than a Catholic and Spanish-speaking Spanish-American immigration, are ignorant and incoherent. With them the days of fet Catala are numbered. At least, and for the moment, the immigrationist nonsense of the Catalanists does not seem to prevail so strongly among the radical Basque nationalist militants.

LT: How would you define the Navarrese feeling of identity?

AI: I think I have already answered in part. For me, Navarrismo is in the past; its hallmarks were Catholicism and traditionalism. It was the same as the Requetés, the red berets that my maternal grandfather admired so much and that today only exist in homeopathic doses. I would say the same about the figure of the noble, catholic, deep-rooted, hard-working and honest Basque of yesteryear.

It seems that the “elites,” the Basque and Navarrese oligarchy or political caste have chosen, I do not know if definitively or not, the path of harmonization and alignment with the values and presuppositions of globalism or alter-globalism (which does not matter), or of the so-called progressive transnationalism. They pretend to believe that the Basque and the Navarrese are defined only administratively or legally from a document or an identity card. It seems that they are eager to populate the future Basque and Navarrese territories with the homo economicus, asexual, stateless and phantasmagoric, so criticized in the past by the Basque-Spanish Unamuno, and by the most important figures of Basque nationalism.

If to this we add the ravages of the terrible demographic crisis, undoubtedly the worst in all of Spain and possibly in all of Western Europe, the prospects are not very encouraging. And, all the while, young Basques listen to Anglo-Saxon music, play “Basque rock,” eat hamburgers, consume drugs (young Abertzales more than anyone else), demand the opening of borders, immigration without limits, aggressive secularism, gender theory, transhumanism, hatred of the state and the history of the Spanish nation, and all the bullshit imported from American campuses. I could just say in French or English: “Grand bien leur fasse /Best of luck to them.” But I have the intimate and terrible conviction that if there is not a quick reaction against them, they will bring us a bleak, raw and bloody future in which our descendants will suffer.

LT: What do you think of Stanley Payne’s statement in the Prologue to your book, pointing out that “The Basque Country is the most unique region in Spain?” What are your feelings towards the Basque Country and towards Navarre?

AI: Stanley Payne belongs to that tradition of Anglo-Saxon historians who almost never lose their cool, or they say things with a certain degree of caution and balanced composure. He is a researcher and historian; but he is also a man and not a robot. That is why he opines, judges and interprets, although always with a certain sobriety and consideration. In the Prologue, he refers to the uniqueness of the Basque language, institutions and history (ignoring ethnicity). Now, he is American. I am not. And if I say that I agree with him when he says that “the Basque Country is the most unique region in Spain” many will say that this is due to my personal preference. Precisely as a result of that Prologue by Payne, a friend of mine, not without a sense of humor, wrote me: “This is very good, although I think that Galicians are more particular than Basques.”

In the book Vascos y Navarros I have tried to be as rigorous, honest and disinterested as possible. I have always thought that true objectivity does not lie so much in a hostile withdrawal, as in a kind of well-intentioned will that is capable of understanding and explaining the ideas of others without giving up one’s own reasons. That said, let me say and repeat here that, despite recent evolutions or regressions and the shortcomings of the pseudo or self-proclaimed Basque-Navarrese political “elites,” the Basque Country and Navarre are my favorite lands.

LT: How do you see the recent history of the Basque Country and Spain from the point-of-view of the French Basque Country?

AI: Partisanship, ignorance or disinterest, not only of the majority of the French but also of the majority of French politicians and journalists, for the history and politics of the Basque Country and Navarre, and more generally for Spain in its entirety – is abysmal, unfathomable. The trend is slightly different in the French Basque Country due to the proximity of the border and the presence of a weak but not insignificant Basque nationalist electorate, representing 10% to 12% of the general electorate. Generally, many feel Basque, but as in the rest of France, most are disinterested in the history and politics of the peninsula, unless a momentous event occurs. As for the small Basque nationalist minority in the north, they tirelessly recycle Hispanophobic clichés, although they sometimes fear being swallowed up by their powerful brothers to the south.

In my case, I have not surrendered. With the help of a handful of young and veteran French historians and courageous editorials, I continue and will continue to explain, denounce and refute black legends, misconceptions, censored data, instrumentalized facts and Hispanophobic nonsense, spread by the ignorant, the wicked and, unfortunately, by a good part of the Basque, Navarrese and Spanish political caste.

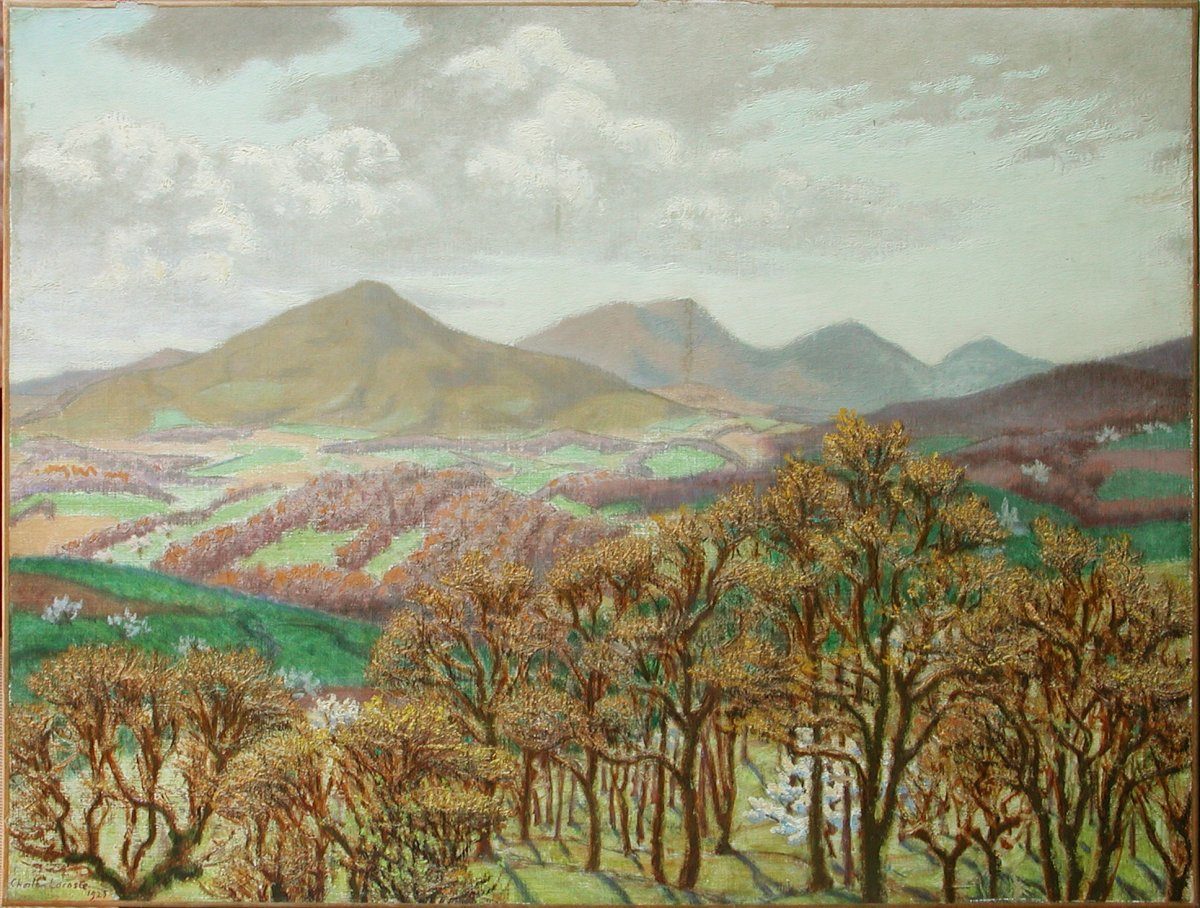

The image shows, “Landscape Of The Basque Country,” by Charles Lacoste, painted in 1925.

The Spanish version of this appeared in La Tribuna del Pais Vasco. Translation by N. Dass.