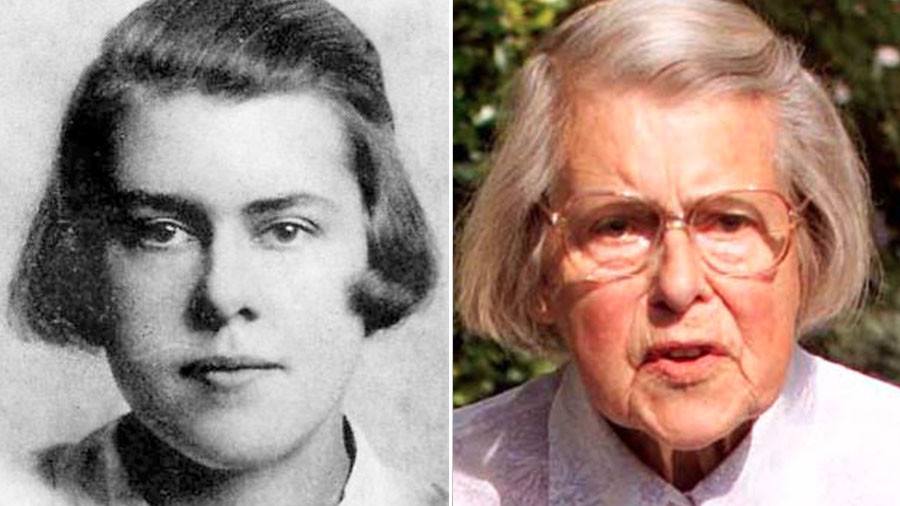

If Winston Churchill was a vehement opponent of Soviet Russia, his cousin Clare Sheridan, on the contrary, was one of its biggest supporters. That in Britain was unforgivable.

“I am not a Bolshevik. But I have tried to understand the spirit of Communism and it interests me overwhelmingly,” wrote Winston Churchill’s cousin Clare Sheridan in her diary, published as Russian Portraits, during a trip to Soviet Russia in 1920.

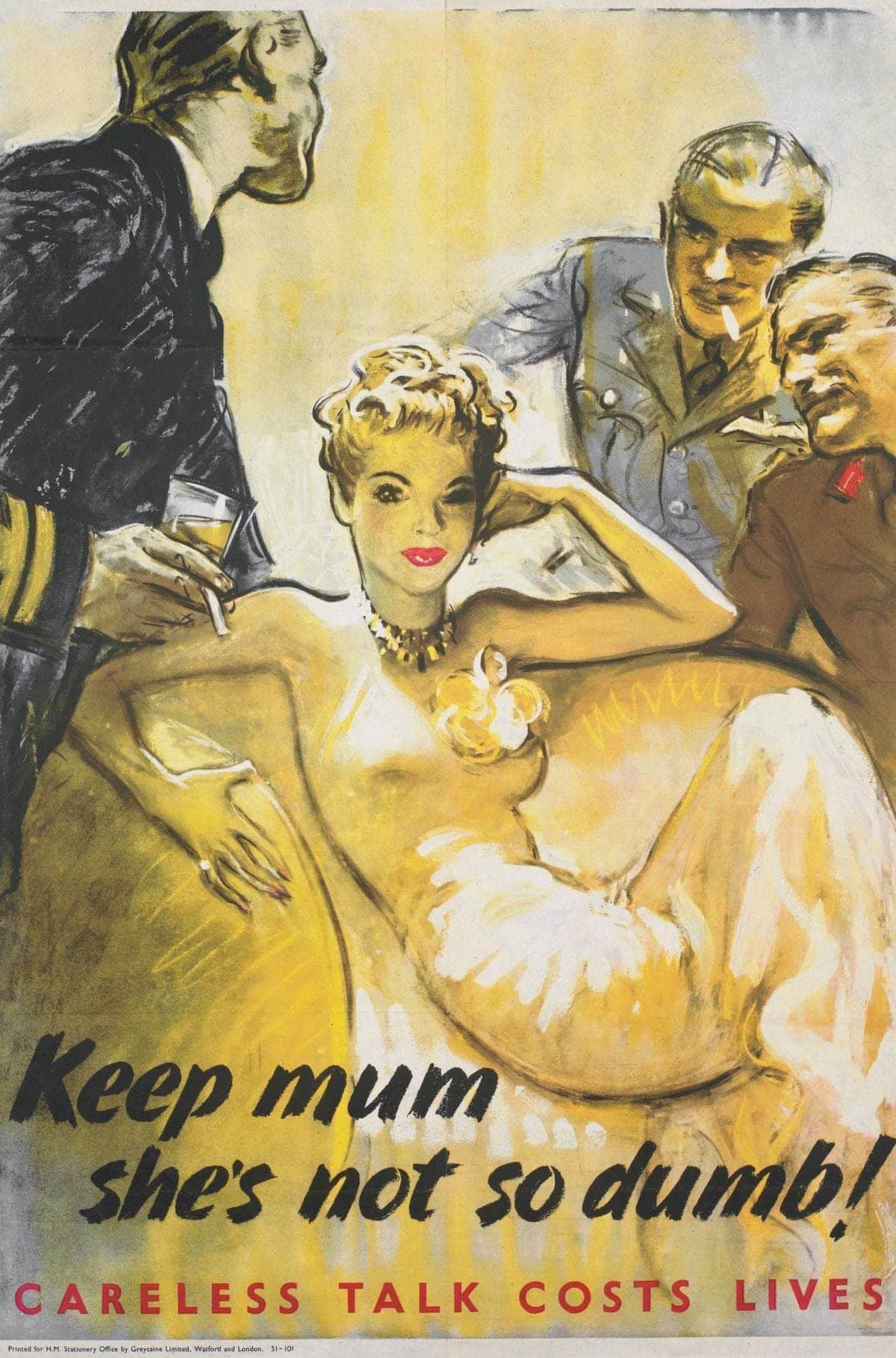

The British counterintelligence agency MI5, however, was not so sure. They believed that this relative of one of the most influential people in Britain was a Bolshevik spy.

Being the cousin of War Minister Winston Churchill was not Clare Sheridan’s only accolade. She was a famous sculptor in her own right, and it was her professional activities that took her to the capital of Soviet Russia.

Having met with representatives of a Soviet trade delegation in London in 1920, Clare admitted to having a lifelong love for Russian literature, music, dance, and art; she was promptly invited to visit Russia.

However, at the time it was very difficult for a British subject to do so. The Entente’s intervention in Russia had only just ended, and some British troops remained in Crimea, the last stronghold of the White armies. Moreover, Britain itself, despite opening trade talks, was in no hurry to officially recognize Soviet Russia.

Visiting the land of the Bolsheviks was viewed as utter madness, but Sheridan cared little for public opinion. Via Stockholm and Tallinn, “this wild cousin of mine” (as Churchill put it) set off for Moscow.

Clare was greeted in Russia as an honorary guest. For two months she lived inside the Kremlin, strolled around the streets of Moscow, visited theaters, observed the lives of ordinary people, and marveled at what she saw: “Why am I happy here, shut off from all I belong to? What is there about this country that has always made everyone fall under its spell?”

“Why are these people, who have less education, so much more cultured than we are? The galleries of London are empty. In the British Museum one meets an occasional German student. Here the galleries and museums are full of working people. London provides revues and plays of humiliating mediocrity, which the educated classes enjoy and applaud. Here the masses crowd to see Shakespeare,” she wrote in her diary.

Clare talked a lot to Muscovites, took pictures, and made notes: “Now for the first time I feel morally and mentally free… I love this place and all the people in it. I love the people I have met, and the people who pass by me in the street. I love the atmosphere laden with melancholy, with sacrifice, with tragedy. I am inspired by this Nation, purified by Fire. I admire the dignity of their suffering and the courage of their belief.”

Nevertheless, she didn’t forget why she had come to the Soviet capital in the first place. Sheridan’s sculptural portraits of Bolshevik leaders included Zinoviev, Kamenev, Dzerzhinsky, Trotsky, and, of course, Lenin.

She even got to have a private conversation with the “leader of the Russian revolution.” Vladimir Lenin jokingly reproached her for being related to “the man with all the force of the capitalists behind him.” In response, Clare remarked that her other cousin was a member of the Irish left-wing party Sinn Fein. Laughing, Lenin replied: “That must be a cheerful party when you three get together.”

At home in Britain, Clare was greeted with a coldness verging on hostility. She effectively became persona non grata in high society, and even Churchill refused to communicate with her, at least temporarily.

Despite Sheridan’s protestations that she was far removed from politics, the British were outraged by her unprecedented trip, friendship with the Bolsheviks, and support for Russia.

MI5, in particular, paid close attention to the British war minister’s cousin. The agency could not overlook Clare’s ambiguous remarks about Russia and Russians: “I should like to live among them forever, or else work for them outside, work and fight for the Peace that will heal their wounds.”

Under intense public scrutiny, Sheridan was forced to leave Britain. She set off on an incredible round-the-world trip, which included an affair with Charlie Chaplin in the US, meeting Mussolini in Switzerland, and hearing the speeches of the young Hitler in Germany. Everywhere she went, MI5 agents followed on her heels.

In 1925 field operatives discovered that Sheridan had handed over details of a conversation with Churchill (then Chancellor of the Exchequer) about foreign policy to Daily Herald editor Norman Ewer, who was believed to be a Soviet agent.

Shortly thereafter, according to MI5, Sheridan’s finances quickly improved, suspiciously so. After a decade of money trouble, she went to Algeria, having paid off all her debts. British intelligence suspected a Russian hand in it.

“In view of the facts regarding her financial position [we] are strongly of the opinion that Clare is in the pay of the Russians and that she has been sent to North Africa to get in touch with the local situation and to act either as a reporting agent or possibly as a forwarding agent,” read the MI5 report.

MI5 repeatedly shared its suspicions about Sheridan with Churchill, but he always chose to ignore them. More than that, with WW2 now in play, Clare and Winston finally reconciled their differences, letting bygones be bygones.

Clare Sheridan passed away in 1970 at the ripe old age of 84. No case was ever brought against her.

Boris Egorov writes for Russia Beyond.

The photo shows a portrait of Clare Sheridan by Emil Fuchs, painted in 1907.