It is regrettable that only a few facts about the life of this great abbess who was venerated all over Scotland and northern England and esteemed by the Venerable Bede are known. Now that the interest in this holy woman is increasing among the Orthodox, let us recall her biography.

St. Aebba, also known as “Ebba the Elder,” was born in about 615, in the royal family of the Kingdom of Bernicia, in northern England. Her father was King Aethelfrith, who ruled Bernicia from 593, as well as Deira (from 604) until his death in 616 (the amalgamation of these two kingdoms was later to be called Northumbria).

Among her brothers were St. Oswald the martyr, and Oswiu, kings of Northumbria. After her father had been killed at the Battle of Bawtry, St. Aebba’s mother Acha took her children to the kingdom of Dalriada, situated in the north-west of Scotland and founded by Irish Gaelic settlers. Princess Aebba was a little girl then. Meanwhile, Edwin, St. Aebba’s maternal uncle, who converted to the faith much later, assumed the Northumbrian throne. At that time, Dalriada was a stronghold of Christianity (by contrast to the largely pagan Pictland in the rest of Scotland and Northumbria in England) – and numerous spiritual and monastic centers sprang up there, the most famous being the Monastery of Iona founded by the Irish St. Columba in 563.

Under the protection of Dalriadan kings, having absorbed the Irish spiritual tradition, St. Aebba and her kinsmen were converted to Christ and baptized.

In the 630s, when her brother St. Oswald became the king of Northumbria and a champion of the Orthodox faith, St. Aebba decided to return to her homeland and help him evangelize the Northumbrians, most of whom were still pagan. In 635, on St. Oswald’s initiative the Irish St. Aidan, a former student of Iona, was sent to Northumbria and founded Lindisfarne Monastery, which became a beacon of Orthodox monasticism, culture and learning.

St. Aebba was beautiful and had suitors, but the princess chose to become the bride of Christ and took the veil in about 640. According to late tradition, she was tonsured on Lindisfarne by St. Finan, who later became the successor of St. Aidan as its abbot and bishop. No doubt, St. Aidan himself was among St. Aebba’s spiritual mentors and friends.

Well instructed in monastic life, and with the assistance of her brothers St. Oswald and Oswiu, the maiden of God in due course established her famous double monastery in Coldingham (its original name, according to St. Bede, was urbs Coludi, meaning “Colud’s fort,” and later became known as Colodaesburg), with two communities of monks and nuns who lived separately and prayed in the same church. At that time, Coldingham was part of Northumbria in England; now it is in the Scottish Borders area of Scotland.

Alas, we know little about the activity of St. Aebba as abbess, but she was noted for her wisdom, exemplary holy life and preaching that contributed to the conversion to Orthodoxy of many pagans. It is likely that in governing Coldingham, St. Aebba imitated her celebrated contemporary St. Hilda, who was abbess of Whitby in Northumbria at the same time.

Aebba’s monastery was situated some twenty-five miles north of Lindisfarne in a very austere place: Coldingham sits on the North Sea coast off south-eastern Scotland, with cold weather, heavy storms and large waves. Until recently, historians argued as to where exactly St. Aebba’s monastery was located. Some maintained that it was in what is now the village of Coldingham, and others—that it was at the Kirkhill overlooking the rocky promontory of St. Abb’s Head (named after St. Aebba) in St. Abbs village with cliffs right by the sea. The archeological excavations led by DigVentures, and carried out from 2017 to 2019, proved that her monastery was in Coldingham—exactly where the present-day Coldingham Priory stands.

This royal establishment enjoyed the influence that may be compared with Lindisfarne. Alas, that prosperity did not last long after St. Aebbe’s death.

Some monks and nuns of Coldingham neglected vigils and prayers and towards the end of her abbacy it was hard for St. Aebba to keep discipline at the monastery. That is why she would ask the great ascetic St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne, an illustrious pastor and wonderworker, to visit Coldingham and instruct its inhabitants. It was during one of those visits by St. Cuthbert that his famous miracle with the otters occurred. Let us cite from Bede’s Life of St. Cuthbert:

“When this holy man was acquiring renown by his virtues and miracles, Ebbe, a pious woman and handmaid of Christ, was the head of a monastery at a place called the city of Coludi, remarkable both for piety and noble birth, for she was sister of King Oswiu. She sent messengers to the man of God, entreating him to come and visit her monastery. This loving message from the handmaid of his Lord he could not treat with neglect, but, coming to the place and stopping several days there, he confirmed, by his life and conversation, the way of truth which he taught. Here, as elsewhere, he would go forth, when others were asleep, and having spent the night in watchfulness return home at the hour of morning prayer. One night, a brother of the monastery, seeing him go out alone followed him privately to see what he should do. But he when he left the monastery, went down to the sea, which flows beneath, and going into it, until the water reached his neck and arms, spent the night in praising God. When the dawn of day approached, he came out of the water, and, falling on his knees, began to pray again. Whilst he was doing this, two quadrupeds, called otters, came up from the sea, and, lying down before him on the sand, breathed upon his feet, and wiped them with their hair after which, having received his blessing, they returned to their native element. Cuthbert returned home in time to join in the accustomed hymns with the other brethren. The brother, who waited for him on the heights, was so terrified that he could hardly reach home; and early in the morning he came and fell at his feet, asking his pardon, for he did not doubt that Cuthbert was fully acquainted with all that had taken place. To whom Cuthbert replied, ‘What is the matter, my brother? What have you done? Did you follow me to see what I was about to do? I forgive you on one condition,—that you tell it to nobody before my death.’ In this he followed the example of our Lord, who, when He showed his glory to his disciples on the mountain, said, ‘See that you tell no man, until the Son of man be risen from the dead.’ When the brother had assented to this condition, he gave him his blessing, and released him from all his trouble. The man concealed this miracle during St. Cuthbert’s life; but, after his death, took care to tell it to as many persons as he was able.”

From the 660s on St. Aebba had considerable influence on St. Etheldreda (Audrey), the future foundress and abbess of Ely Monastery in what is now Cambridgeshire. In 672, St. Etheldreda was separated from her nominal husband, King Ecgfrith of Northumbria (670—685; Aebba’s nephew), took the veil and for some time lived at Coldingham under St. Aebba’s guidance before travelling south to the Isle of Ely.

St. Aebba communicated with other contemporary saints too. She interceded for the great missionary, bishop and builder of churches St. Wilfrid of York, who more than once was treated unfairly by royalty. In 681 the same King Ecgfrith visited St. Aebba’s Monastery with his second spouse, Ermenburga, who was struck down by an illness after the unjust imprisonment of St. Wilfrid and the theft of the holy relics brought by Wilfrid. This episode is narrated in the earliest Life of St. Wilfrid by Stephen of Ripon, an extract from which we quote below:

“In the meantime the king and queen were making their progress through the cities, fortresses, and villages with worldly pomp and daily feasts and rejoicings, in the course of which they came to the nunnery of Coldingham. The abbess, King Oswiu’s sister Aebbe, was a very wise and holy woman. At this same place the queen was possessed by a devil during the night and, as in the case of Pilate’s wife, the attacks were so severe that she was hardly expected to last till day. As dawn was breaking the abbess came to the queen and found her lying with the muscles of her limbs all contracted and screwed up. Obviously she was dying. Off went Abbess Aebbe to the king and with tears in her eyes gave her opinion of the cause of the calamity. Indeed she rounded on him. ‘I know for a fact that you ejected Wilfrid from his see for no reason. He was driven into exile and went to Rome to seek redress. Now he has returned from that see that has the same power as St Peter himself in loosing and binding. And what have you done but despised its injunctions and despoiled the bishop? Then to pile injury on injury you have had him locked away in jail. Listen, my son, to your mother’s advice. Loosen his bonds. Restore the relics your queen has taken from his neck and carried round from city to city like the ark of the Lord to her own doom. Send a messenger with them. The best plan would be to reinstate him as bishop, but if you cannot bring yourself to do this, at least let him and his friends leave the kingdom and go where they will. Do this and you will live and your queen will recover. Disobey and, as God is my witness, you shall not escape punishment.’ The king obeyed the holy matron, freed our bishop, and let him depart with his relics and friends. And the queen recovered.”

During hat time there lived a holy recluse called Adomnan (Adam) in the Coldingham community of monks under St. Ebbe (feast: January 31). He was born in Ireland, ordained hieromonk, and during his pilgrimage to Scotland remained at Coldingham. (He shouldn’t be confused with his great namesake, St. Adomnan of Iona, the author of the Life of St. Columba).

Adomnan excelled in the ascetic life, the strict observance of all monastic rules and denounced those members of the community who behaved in a disorderly way. In a vision it was revealed to him that in the future the monastery would be destroyed by fire because of “the frequent gossip and frivolity” of some of its monks and nuns. Hearing this prophecy, the negligent monastics mended their ways, but not for long. After the deaths of St. Adomnan (c. 680) and St. Aebba a disaster befell the monastery – it was destroyed by fire in 686, though rebuilt soon afterwards.

After 870, monastic life was not resumed at Coldingham for a long time. Little by little the waves washed away the original beauty of Coldingham, St. Abb’s Head and Ebchester, but no waves could ever erase the memory of the virtues of their foundress, Aebba, in people’s hearts.

In the late eleventh century, after the Norman Conquest, the relics of St. Aebba were rediscovered and in 1098 King Edgar I of Scotland (1097–1107) endowed lands for the new Roman Catholic Benedictine Coldingham Priory in honor of the Virgin Mary, St. Cuthbert and St. Aebba (later often referred to as the Priory of the Virgin Mary). Its church was consecrated in 1100, but the priory was officially established under King David I of Scotland (1124–1153). The Priory brethren consisted of monks who came from Durham. It grew into one of the largest and most flourishing in Scotland and a center of the wool trade.

Thus the veneration of St. Aebba was revived all over Scotland and across northern England. Part of St. Aebba’s relics was kept at Coldingham, and another part in Durham. Among medieval figures associated with Coldingham, let us mention Monk Reginald of Durham († c. 1190), who composed his version of the lives of St. Godric of Finchale, St. Oswald of Northumbria, and wrote an account of St. Cuthbert’s miracles and preserved a sermon of St. Aebba of Coldingham, where he may have lived for some time. The Priory also produced Geoffrey of Coldingham (+ c. 1215), its sacristan and a chronicler, who recorded the history of Durham between the 1150s and 1215 and probably composed the lives of St. Bartholomew of Farne and St. Godric of Finchale.

A true gem is kept at the British Library in London. It is the Coldingham Breviary, created in the late thirteenth century, by a monk of Durham (Coldingham Priory was a cell of Durham Monastery and later of Dunfermline Abbey) for Coldingham Priory. This beautiful manuscript in Latin and French contains the calendar of local feasts and commemorations (such as the dedication of the altars of the Archangel Michael and St. Aebba at Coldingham Priory, the consecration of the church in Coldingham, etc.), along with the texts for the feasts read during the year, and hymns and psalms to be read weekly, complete with illuminations. Among the relics once kept by the priory were a tiny piece of the True Cross and a nail with which the Savior was bound to the Cross. However, the Priory was almost wiped off the face of the earth several times over its history—for example, by King John of England in 1216, during his punitive expedition to the north after signing the Magna Carta.

Coldingham Priory was of such great renown that King James IV of Scotland included revenues from this monastery among the gifts to his wife, Queen Mary Tudor, for their wedding in 1503.

In 1560, during the Scottish Reformation, Coldingham Priory was dissolved, the relics of St. Aebba and other holy objects destroyed, and its lands passed to a local landowner. The Priory’s demolition was completed in 1650, when Oliver Cromwell besieged it and drove out some Royalists who had taken refuge inside it. Later it was extensively used as a quarry by locals. In 1852 a splendid new church was constructed in Coldingham using the materials from the Coldingham Priory ruins. This church is open to this day. It belongs to the Presbyterian Church of Scotland and is called “Coldingham Priory”. Although the current church is huge, it comprises materials from only one section of the former monastery’s choir. Recently work to improve the state of the Priory ruins was carried out and theme gardens dedicated to its history were added. The remains of the original monastery of St. Aebba were unearthed beside this church in 2019. The radiocarbon analysis results showed that the fabric, materials and butchered animal bones are from the Anglo-Saxon period—between 660 and 860 A.D. Among the most impressive finds was the original ditch, or vallum, that surrounded St. Aebba’s Monastery.

Today only remains of the wall foundations, chapel ruins and a well survive from the supposed community of St. Aebba at St. Abb’s Head near Coldingham. Interestingly, no finds of any significance were made during excavations at St. Abb’s Head, as opposed to a wealth of discoveries at the Coldingham site. This indicates that there was no permanent community at St. Abb’s Head throughout its history, apart from the buildings whose ruins are mentioned in the article. Coldingham is slightly further inland, and it was logical if St. Aebba set up her main community there. As for St. Abb’s Head, the saint may have used it for quiet prayer and retreats.

The remains are concentrated on the headland called Kirkhill close to the lighthouse at St. Abb’s Head, a local landmark. The chapel was built in the Middle Ages by the neighboring Coldingham Priory to perpetuate the memory of their pre-Norman predecessors. This place was visited by many pilgrims in the late Middle Ages and miracles were worked. Thus, a girl who was blind in one eye and deaf in one ear was healed after praying at the chapel for fifteen nights.

In his work, Britain’s Holiest Places, Nick Mayhew-Smith mentions two small coves beside St. Abb’s Head; one of them was certainly used by St. Cuthbert for nocturnal prayer in the waters (the Horse Castle Bay). The other cove preserves a well chamber, which was popular among pilgrims in earlier days who came here to commemorate the local saints; another well which reportedly has water in it is close by and is dedicated to St. Aebba (this second bay is called the Well Mouth). This area offers spectacular views of the seashore, with recurring howling gales and waves crashing beneath, as in the time of St. Aebba.

The village of Ebchester in County Durham stands on the site of the Roman fort of Vindomora. It was believed that St. Aebba founded one of her monasteries here, but it was subsequently plundered by pirates and never restored. The village church is dedicated to St. Aebba and dates back to the eleventh or twelfth century, its foundations being pre-Norman. However, no traces of an earlier monastery have been found so far. In the Middle Ages this isolated and rural spot attracted many hermits and it was known as a haven for anchorites.

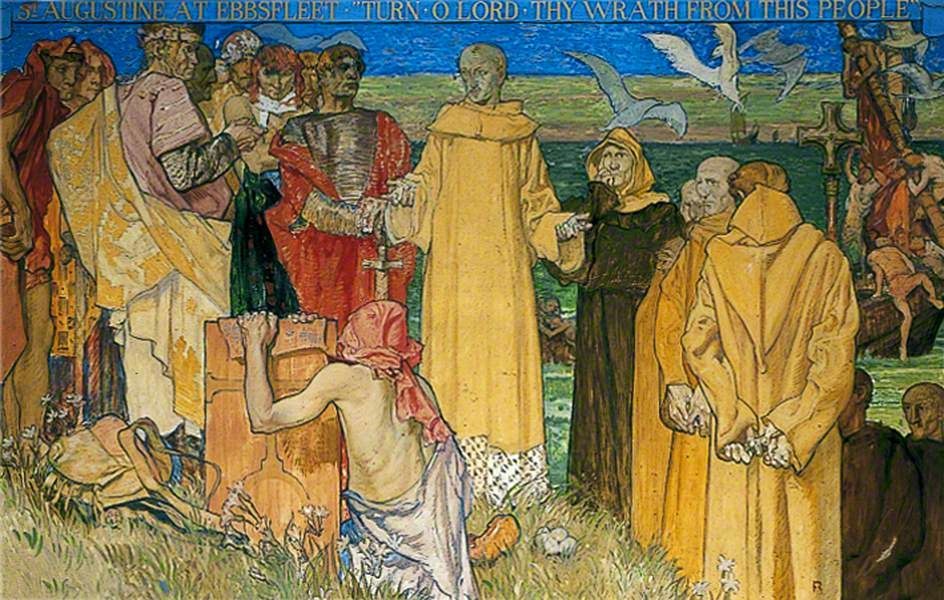

There is St. Aebba’s Church in Beadnell village in Northumberland, which has a stained glass window depicting Sts. Aebba and Oswald. The village sits on the North Sea coast not far from Bamburgh. The church was built as a chapel in the eighteenth century and rebuilt in the following century. Apart from this there is a narrow promontory called Ebb’s Nook on the edge of the village, where in 1853 a very ancient stone chapel was dug up. The chapel was dedicated to St. Ebba and dated back to the thirteenth century. During the latest excavations in 2012 many burials, much earlier remains and a series of earthworks were found around it, presumably of the seventh century, enabling historians to suggest that St. Ebba may have founded a hermitage/skete here and the later chapel was erected to commemorate her. Now the site is carefully preserved.

There is the Episcopalian St. Ebba’s Church in the fishing town of Eyemouth in the Scottish Borders of the Diocese of Edinburgh, built in 1887. There used to be a St. Abb’s holy well beside the famous Ayton Castle at Ayton village in the Scottish Borders.

Finally, a district, a street and a parish church in the city of Oxford are named after St. Aebba (“St. Ebbes”). Historically, it may have been the oldest parish church in this university city. Though its origins are unknown, it formed part of Eynsham Abbey in Oxfordshire in 1005, and even then it was referred to as “a very ancient church.” St. Aebba is depicted in it on an old stained glass window. According to one version, the presence of a St. Aebba’s Church so far in the south is explained by the fact that she may have accompanied her brother St. Oswald to the nearby Dorchester-on-Thames to attend the baptism of King Cynegils of Wessex by St. Birinus, the enlightener of this region. Thus this church may have been built to commemorate the holy maiden’s visit to the area. The present church was almost wholly rebuilt and enlarged in the nineteenth century, while retaining some medieval monuments, stained glass and communion plates; over its history it was connected with some outstanding figures.

Perhaps this holy princess, one of numerous seventh-century powerful early English women, should be revered on a par with her brother St. Oswald, who founded Lindisfarne Monastery, making history and enlightening the north-eastern England. Likewise, his sister, St. Aebba founded Coldingham, made history and contributed to the enlightenment of south-eastern Scotland. They truly are two stars—two of a large number—shining in the firmament of seventh-century Britain.

Holy Mother Aebba, pray to God for us!

Dmitry Lapa writes for Pravoslavie on Church history.

The featured image shows, St. Ebba in stained glass from St Ebba’s Church Beadnell, Northumberland.