It is said that there is something about the revolutionary spirit that affects the eyes and produces a certain blank darkness that seems to be a conduit to the abyss of anarchy. I have heard of this phenomenon from riot police and have read of it in accounts of convulsive historical episodes. Whenever a seething mob in this or that epoch had its turn at wreaking wanton destruction, those eyes appear amidst the howling throng.

A sort of collective madness can grip and coalesce a disparity of individuals and thrust them into unified action. One thinks of thousands of bees uniting to swarm and sting a victim to death. Each tiny and relatively harmless unit of the frantic whole takes its turn at injecting a bit of rage drenched poison until the victim, who is himself stronger than any single one of the revolutionary units, is lain paralyzed and ready to be devoured.

Hilaire Belloc, with his famously keen ability to see most deeply into the interwoven strands of human motives that move history, described in such terms the almost impossible knit pattern that convulsed Paris during the Reign of Terror.

Grotesque and demonic in its coordination, it was an eruption that was immortalized by the bloody blade at the open-air horror chamber called the Place de la Nation. The dead-eyed Thing sated itself when it ritually sacrificed a Catholic King and his Catholic Queen at the hideous altar and divided France forevermore into avant et après.

I believe I caught scent of that rancid fume in the Spring of 2020 in the City of Richmond, Virginia. Similar to the Paris of 1792, the stars aligned to set all the pieces in place for a series of enraged, anarchic acts of mob terrorism that set America’s cities afire and tore its symbols to the Earth in a frothy insanity.

After suffering a year of medical tyranny disguised as concern for the public health in the face of the Wuhan virus, Americans were well primed for a cathartic paroxysm. The lockdowns, more a psychological compliance test than a shield against disease, were to be thrown off in a torrent of rage. The defining moment that Spring was the viral footage of a disturbing scene from the streets of Minneapolis whose optics provided a crisis for the opportunists that was too perfect to be forgone.

Deft hands lit and seized the torch of revolt. Neo-Marxist action cells camouflaged as a civil rights movement materialized, organized and masterfully funded the hatred.

An “anti-facist” Fascist cult emerged from the shadows to rage at our fellow countrymen, our land and our mores. America must burn. The fires were lit in city after city. More! America must be culturally purged, torn down, expurgated, remade in a new image and likeness.

This was no mere spontaneous congeries of lawful protests against injustice. It was a call to eradicate an historically revised, wicked and irredeemable national past. Along with it came the furious demand that all must conform even in thought. Those who dared resist were branded as not “woke.” Those who conformed were sentenced to the perpetual self-flagellation of victim or oppressor. No one was to truly uplifted.

The ancient, venomous serpent was stealthily slithering through America’s streets and institutions, inciting unbridled passion, chaos, mischief and hatred. The fabric of society was tearing at the seams.

Somehow it was the same spirit that raged against the Cross in 1920s Masonic Mexico; that extinguished the lives of 5,000 priests, monks and nuns in 1930s Socialist Spain; and that crushed the venerable traditions of China in Chairman Mao’s Communist cultural revolution.

And it was on display before me as I walked one twilit Spring evening along Virginia’s arguably most elegant of promenades: Monument Avenue.

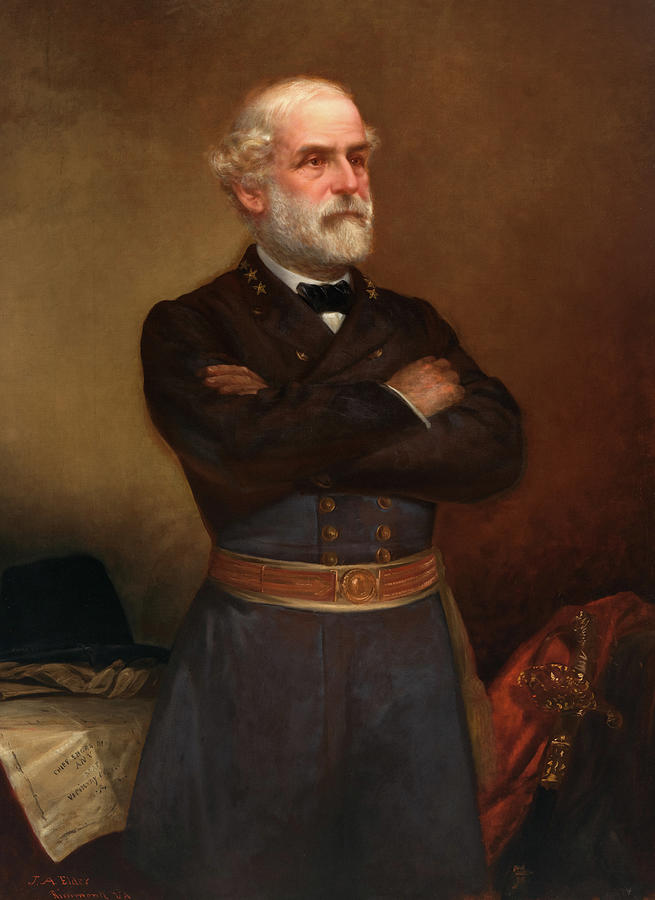

Thinking that the fury of the previous nights’ riots had ebbed away, and accompanied by two confreres in the priesthood, my walk led me to the epicenter of the Avenue. This is a grassy, rotund park bounded by a normally slow-moving traffic circle. In the center stood the equestrian statue of General Robert E. Lee, high and noble atop a classical pedestal.

But the lawn about was strewn with detritus and the pedestal was absolutely covered in wrathful graffiti: “ACAB! All Cops Are Bad,” “F- the Cops.” Some revealed a deeper animus, “Kill the Honkies!” And ubiquitous was that which exposed another but apparently related disorder: “Black Trans Lives Matter!” “LGBTQ rights!”

That evening after the attack, people were circling about as if they were inspecting the fallen body of a victim whose corpse yet awaited mutilation. I wore a black soutane as we walked amidst a tense and gathering crowd that we had not anticipated encountering. For this was to be another night of riots, in which the statues were begun to be torn down.

The Virus had given convenient cover for the donning of face masks, which under ordinary legal conditions were not permitted in public, for obvious and sage reasons. We noticed the steady arrival of young adults hidden behind bandannas, sporting suspect backpacks and riding in on skateboards that seemed to have become the official steed of the new revolt.

Everyone could feel the impending outbreak of some new violence. It seemed as if the swarm was ready to descend upon its prey at the first attempt of Order to reimpose itself.

We were met with several tentative, almost guilty greetings of, “Good evening, Fathers.” But for the most part there was a studied suspicion coupled with furtive glances cast at one another. As we were readying to extract ourselves from the foreboding gathering, a young blonde woman with her little dog Toto, apparently stationed at our parked vehicle, hissed menacingly, “Where are you from?” I had never seen her before, yet there was instant mutual recognition as our eyes locked. We made our exit, only to find a nail in one of the car tires, which fortunately did not halt us until we were safely distant from the maelstrom of malevolence.

I was a young boy when I first saw the film “Doctor Zhivago.” And one unforgettable scene was loosed from my memory that night in Richmond. It was when Zhivago returned to his Moscow town home after it had become occupied by hostile, triumphant Bolsheviks. He was allowed one room of his former abode. A new order had been emplaced. His bourgeois presence was being tolerated, but the scene well conveyed that he was in mortal danger.

This in turn was reminiscent of the captivity of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette in their own Palace of the Tuileries—tolerated until the anarchy could remake the rules that would give cheap legal cover for the planned regicide they lusted after. Richmond’s Lee Circle had evidently become an associated occupied territory. And our presence, as representatives of a sort of anachronistic “First Estate,” palpably fit ill in this new order of things.

That riotous night the statues gracing Monument Avenue began to succumb to the grasping mob: President Davis first, then Stonewall Jackson and General JEB Stuart a few days later. Yet beyond those three, Lee in statuary still stood, as if in historical witness to his renowned military and moral intractability.

In fact, the ensuing year would prove that it was found impossible to topple him by brute mob force. There was uncovered a law which took the matter out of the Richmond Commune’s hands. Higher authorities and yet more force were being called out. Lee in monument, as in life, proved too great for easy defeat. Lincoln had required five successive Yankee generals and a change in strategy to conquer Lee. So too with his mere statue. For the ochlocracy ironically yet pathetically needed organized authority to achieve its goal.

In the final phase of the siege, the revolutionary Earl of Richmond, together with some occult combination of socio-political powers, moved the Supreme Court of the Commonwealth of Virginia to vote against the monument’s more than centenary presence. But that was to take time to accomplish; just as it took ten months to dislodge Lee from the vast network of trenches that defended Richmond and Petersburg from 1864 to 1865.

Months later, on a sunny, calmer Autumn morning, we returned to Lee Circle to behold his monument still towering defiantly over the commune.

An ominous man sat high upon the pedestal’s ledge as if he were a sentinel, ready to summon the revolutionary guards at a moment’s notice. Others walked about or lounged on the pedestal steps. A basketball court had been set up, a tenacious community garden had been planted and memorials to victims of police-inflicted “extra-judicial executions” ringed the circle.

By then fully seven layers of graffiti encrusted the pedestal. It was diabolical graffiti. Nothing spoke of harmony, there was no citation of Holy Writ. This clearly was not the Civil Rights Movement revisited. It was red Hegelianism synthesized for a weary and vulnerable America. Still, there stood Lee, tall and miraculously untouched.

We cautiously strolled around the circle when we were approached and invited into the fortifications’ sanctum. There we spent a part of the morning conversing with activists who told us their version of events. It was an undramatic but valuable exchange of views. We learned their names, their stories and their hopes. I sat on the monument steps and met an elderly, black gentlemen who was apparently born again, a younger black gentleman who was a zealous activist and a third who served to fill the ranks and give tours.

I asked about the graffiti. Why was it tolerated that someone had scrawled a slogan calling for the killing of all white people? They protested that they did not advocate such measures.

Did unborn black lives matter? If so, why was it nowhere indicated? A young man took up can of spray paint to scrawl his agreement with me. But the can had been spent, almost as a sign that the sloganeering spirit would neither address nor tolerate the deeper matter of the inherent dignity of all innocent human life.

Why was there a preponderance of LGBT graffiti? Because they “supported us.” “Who is supporting whom?” I wondered. The elderly man, when queried, actually had no idea what LGBT even stood for. But he told me that “God Himself” had visited this place and laid it waste. I thought to myself, “Sir, to which god do you refer?”

I sat between them as they smoked marijuana, passing it back and forth under my nose, oblivious of basic etiquette. They dutifully wore the Covidian compliance masks, albeit beneath their chins. Carelessly, and in violation of all the pandemic fatwas, they shared the same unsanitary joint. It was in a sense a refreshingly frank acknowledgement of the absurdity of the mask mandates. If only we knew in 2019 that weed kills the Virus.

In the end, we parted amicably enough, and I was grateful for having had a chance to converse without shouting or the throwing of bricks, albeit in such a place of disorder and impending doom.

My next visit to Monument Avenue was on September 7, 2021. The revolutionary authorities had decreed that the statue of Lee was to be taken down the very next day by Uruk-hai-esque machinery. Lee’s term of tense house arrest had come to its conclusion and the gallows awaited.

It was a clear, sunny day when we beheld the monument for the last time. A huge black fence had been erected around Lee Circle. The police were at last ubiquitous. This made me think of how the Jacobins arrayed conscripted soldiers about Madame Guillotine to protect their state sponsored terrorism. A new kind of order had emerged.

A comrade, clearly of leftist sympathies, stood just outside the Circle with a semi-automatic rifle slung over his shoulder and sidearms strapped to his body in a twisted display of Virginia’s legal open carry laws. He was exercising his Second Amendment right to bear arms in a most threatening way—an added irony to the Left’s obsession with disarming law-abiding citizens.

Suddenly, a pickup truck with Tennessee plates and flying the emblematic Battle Flag circled the statue, paused, and laid a strip of rubber on the pavement in front of the statue as if by way of proffering a virile final salute to “Ol’ Marse Robert.” Immediately a city police cruiser with lights flashing appeared from a hidden vantage point and chased the young recusant down.

This had a patent absurdity about it. In a place where the authorities had not only tolerated but even protected a sustained months-long vandalism of public property, the Law was suddenly and hypocritically to be applied in exacting detail. That sole pick-up truck driver dared raise a voice of objection to the next day’s execution. But no dissent would be brooked. The “voice of democracy” apparently had its limits. The First Amendment be damned.

We walked about the perimeter, declined an interview with a reporter and cameraman, but soon enough were engaged in sundry private conversations.

We met a community organizer/student of social work, who told us of how nicely the plan was unfolding and of the excitement over the next day’s “festivities.” She voluntarily and dutifully informed us of her vaccination status and pointed out that she was also observing the Center for Disease Control’s six-foot social distancing rule. It all dovetailed in a neatly pathological fashion.

An elderly black woman then approached us, and looking furtively to right and left, said in an almost whispered voice, “I had no problem with these statues. We all know the history. This was a beautiful avenue for our City before they wrecked it. And I do not think for one minute that what is happening is about helping black people.” She lived in the neighborhood but said she had to be careful expressing her views for fear of being beaten up by one of the peaceful protesters.

The scene was tragic for so many reasons. Beyond the obvious ugliness left in the riots’ wake, it was based on bald untruths about General Robert E. Lee.

Here was a grand monument to an American of genuine and unusual character. A member of one of Virginia’s founding families, Lee was a West Point graduate who had at first disfavored secession. After the Deep South had seceded, and during the brief interval when Virginia still clung to the Union, Lee had been offered the command of the Federal Army. Yet in a decision steeped in the virtue of patriotism, he decided in favor of his family and his more fundamental “country” which was the Old Dominion State.

His decision was pregnant with political and moral depth, for it perfectly represented the ethos of the Old Union whereby the several States understood themselves as having freely entered into a federal compact and maintained their right freely to depart therefrom. His refusal to lead a military force into Virginia and against his fellow Americans and family is an essential element of his enduring legacy to both North and South. And it is this legacy which both then and now posed such a threat to the bloated centralizing Leviathan which can quarantine the healthy and tax the pennies on a dead man’s eyes.

Lee had effectuated the emancipation of his family’s slaves before the Emancipation Proclamation farcically only freed those held in bondage in territories not held by the North. In other words, the Emancipation Proclamation effectively freed no one.

It was even excoriated by the Vatican’s L’Osservatore Romano for its implicit incitement to insurrection and murder of defenseless women and children in the South (which, to the everlasting honor of the blacks, did not transpire). Frederick Douglass himself is said to have criticized the Proclamation for its duplicity and trickery. Rather, to the Thirteenth Amendment goes the credit of freeing the slaves. And even then, a special Act of Congress in 1866 was required to liberate the blacks held in servitude by the Native Americans in the Indian Territory. There was ample hypocrisy to go around.

Yet Lee, it might fairly be argued, was the South’s leading moral voice advocating the arming of the slaves leading to their gradual and eventual total emancipation. His position so disconcerted the editors of the Charleston Mercury that they dared to question whether he was a true Southerner at all. In so doing they themselves reinforced a monolithic but ultimately questionable attribution of the roots of secession.

Some Confederate apologists argue that economics and power were the true underlying causes. The banking and mercantile North needed the agrarian South with its vast and exploitable produce. For example, the North wanted a high tariff and the South was disadvantaged by it.

And while there was rightly genuine concern over the moral issue of slavery, there were also Northern States that would not allow blacks to settle on their turf, even as four other Union States were themselves slaveholding (Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky and Tennessee). Many Northerners did not want to compete with a slave labor system, for purely economic reasons.

There was even a brief and failed attempt in 1804 by New England to form its own Confederacy and secede for purposes having nothing to do with slavery, but rather for money and the balance of power.

After the Constitution was ratified, legend has it that Benjamin Franklin referred to the new nation as “a Republic, if you can keep it.” This would not have been a reference to the contradiction of slavery in a government of the people, but rather referred to the nature of republican government in a territory so large and diverse. Franklin knew that, historically, republics tended to turn into monarchies or empires over the matter of conflicting power interests.

It seems fair to wonder whether those deeper roots of secession go back to the fact that the English Colonies were settled by disparate cultural and religious emigrant tribes from the British Isles that harbored a mutual animosity going back at least to the English Civil War.

The deadly serious Puritans of New England, the colorless Quakers of the Delaware Valley, the aristocratic Cavaliers of the Chesapeake and the hardened Scots-Irish of the mountain Backcountry were historically ill disposed to submit one to another, constitutional conventions notwithstanding

Could the matter of slavery have been a confusing decoy rather than the root cause of the conflict? Its presence in the new nation “conceived in liberty” surely disoriented both North and South. But if the United States of America were one indivisible Union, then that Union perforce was itself slaveholding, and both sections profited from it and were guilty of it in one form or another.

The development of pro-slavery thought in the English colonies progressed and hardened alongside a parallel movement of increasing discomfort. Thomas Jefferson said slavery was like “holding a wolf by the ears.” In the grievances he listed against Great Britain, one was that they had saddled the colonies with the awful institution.

The thing had to go. But the question of whether or not the Northern invasion constituted a just war or a crusade to free the slaves needs to be thoughtfully challenged.

Another question is whether a secession movement is accurately termed a “civil war.” The South was neither seeking to impose its control over the whole nation nor trying to conquer the North. It just wanted political separation under the most amicable terms possible. After his defeat, Jefferson Davis longed for his case for secession to be brought before the Supreme Court, but Chief Justice Salmon Chase quashed it because he knew the North could not win the case.

Now reflect for a moment on how the pub-dwelling revolutionaries of Boston provoked a fight with the mighty British Empire that they were doomed to lose without Virginia’s help. The Puritan Yankees fired the shot that was heard around the world at Lexington. But it was at Yorktown in Virginia where their skin was saved by the Southern slaveholding aristocrat George Washington (and King Louis XVI’s armada).

Given all these considerations, pace the Charleston Mercury’s insult, Robert E. Lee should be held up as a true Southerner in the most noble sense, as well as a genuine American patriot in the broadest sense. He is said to have looked with astonishment as Americans broke taboo and actually bombarded the American city of Fredericksburg, referring to them with dismay as “those people.”

This nobility of character and righteousness of cause was, I maintain, somehow intuited by Lincoln and Grant when they came to the realization that in order to defeat the South the toppling of Lee had to be the essential strategic goal. Conquering Richmond or mere territory would never suffice. For as long as Lee remained on the field of battle the hope of Southern independence would survive.

When the more realistic Southern politicians put aside their peanuts and admitted the impending demise of the Confederacy, Lee was even approached with the suggestion that he take the Cromwellian option and seize military control over the civil government that endlessly debated to the detriment of the dire exigencies of war. He refused. His honor and dignity were above such a measure. Either the South would win by constitutional authority and civilized warfare or it was not worthy of the victory.

Little is written about the Southern debate over emancipation. But it is a disservice to historical truth to be unaware of the phenomenon. For there was indeed a movement away from the institution of slavery which involved the military, the press and a segment of Southern politics.

In 1862 a Catholic Confederate Congressman from Louisiana named Duncan Kenner, purported to be its largest single slaveholder, urged President Jefferson Davis that emancipation was necessary to win European recognition and Southern independence. Davis demurred, not seeing, similarly to the original Lincoln, how anything but Congress could bring about such a change.

By 1864 there were increasing calls for the arming and freeing of the slaves issuing forth from Southern military commanders, most notably from General Patrick Cleburne who proposed the immediate enlistment of a quarter million slaves, who would subsequently be freed, and who undoubtedly would fight for what was their Southern homeland as well.

Davis made his first cautious political move via his Autumn Address to Congress. This set off a vigorous editorial debate in the press of both warring sections, and even from far off London. On either side the more astute understood Davis’ courageous epiphany as a tectonic shift vis-à-vis slavery which was so longed for by the better consciences both North and South.

Another Louisianan, Judah Benjamin, risen to the status of Confederate Secretary of State (and the first Jew in any administration), was a key proponent of the arming of the slaves cum emancipation. What coalesced was a crucial and complex meeting of the minds between Davis, Benjamin and Lee.

President Lincoln had clearly stated that the ultimate goal of the invasion was not emancipation but the preservation of the Union. He would save the Union if it meant freeing all the slaves, leaving them all in bondage or freeing only a portion of them. He apparently held political union as more indissoluble and sacrosanct than the Sacrament of Holy Matrimony itself. You can check out any time you want but you can never leave the Union. But he didn’t always hold that view because he had previously defended the right to secede.

Didn’t the Thirteen Colonies secede from the British Empire? In our modern age it seems almost a dictum of Western political etiquette that when a region holds a referendum on secession, it should politely fail by less than one percentage point. If Quebec ever successively votes for secession from Canada, will Ottawa crush it with military force?

In contrast, the South, despite its lofty manners, voted absolutely and overwhelmingly in countless referenda and via their legitimate elected representatives to secede. When the Appalachian counties demurred, Lincoln recognized their secession from Virginia, even though the Constitution forbids any State from having its territory reduced without its consent. Is West Virginia a legitimate State? Maybe one shouldn’t even talk about the right but rather the power to secede. Afterwards one can justify the results with high-principled language.

Be that as it may, in a twist of irony, the Federal and Confederate chief executives actually ended up on the same page regarding this key issue. For in those final months Davis was arguing the point that the South was not ultimately fighting for slavery, but for Southern independence. And he was willing to assert this despite his own status as a major slaveholder, the language of the secession decrees and the apoplexy of the slavocracy.

In another twist, Lincoln reportedly enjoyed reading Karl Marx’s columns in Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune. Lincoln even received laudatory correspondence from that hirsute dialectical materialist and Father of Socialist Slavery.

An American capitalist tourist can with astonishment gaze upon a statue of the Great Emancipator in communist Havana’s Museo de la Revolución. The reader may ponder how Lincoln has taken a place in that island plantation’s Pantheon of heroes. There the devotees of San Fidel, Guevara and Cienfuegos (la asi dicho verdadera hermandad), looking up from their food ration cards with Stockholm Syndrome stares, will tell you: “At least we there is no more Mafia in Cuba.” All that is left is Meyer Lansky’s photo in the bar of the Hotel Nacional. And of course, Don Raúl.

The vilified Jefferson Davis, on the other hand, corresponded with Ven. Pope Pius IX and, despite being an Episcopalian, called the Catholic Faith “mon premier amour.” That correspondence can be seen behind glass in Richmond’s formerly named Museum of the Confederacy. The Roman Pontiff was not in favor of slavery. But we have on record in the memoirs of Odo Russell, the British Minister to the Papal States, that Pius IX “favored the Confederacy” and urged gradual emancipation with due care for the newly freed slaves.

Mr. Lincoln’s War was a watershed event which helped to transform the Republic into an Empire wherein the States were at last definitively subordinated to Washington. Meanwhile, Davis’ adherence to the original constitutional principles could not prevent the disappearance of that Old Republic of the “several sovereign States,” not to mention the emasculation of the 10th Amendment. Now we have the delights of the Administrative State, FBI raids, an army of IRS agents on the prowl and an Empire going the way of all empires, i.e., into the trash bin of history.

Few even know that the Confederate Constitution was virtually identical to the Federal, yet with one term of six years for the President, the prohibition of the use of Federal Treasury funds for special interests and, interestingly, a ban on the importation of slaves.

In any event, in December of 1864, Davis summoned Kenner to Richmond and tasked him with a top-secret mission to go as Confederate emissary to France and England seeking recognition in exchange for emancipation. How or whether he could have pulled that off is up for speculation, but it demonstrates an intriguing point about slavery vs. independence as the fundamental motive for secession. Maybe it was the occasion, but not the final cause.

France would have consented to this proposition but not without England. In turn, Lord Palmerston killed the plan as being too late in the conflict, and dashed the last hope of the South for European recognition and support.

Duncan Kenner, meanwhile, molders in his grave at Assumption Cemetery in New Orleans, awaiting the Last Day when we will all be truly liberated from this world of slaveries and contradictions.

In the broad ranging conversation about the War, one can cherry pick quotations from friends and foes, North and South. The damnable drama that left 600,000 soldiers in Southern dust is just too complex to summarize on an index card. But these discomfiting points of history need to be made known and understood if we are to regard ourselves as truth-seekers and not ventriloquist dummies sitting on the laps of critical race theory ideologues.

Again, one ought not to read too much nor too little into the historical record. Certainly, one must not paint all Southerners with the same broad uncritical brush. Chattel slavery was undeniably being upheld as a positive good by many powerbrokers. But not by all of them and not by the best of them. And the vast majority of Southerners did not even own slaves.

Neither must one naively embrace the fairy tale of gallant Yankee farm boys in shining armor kissing their sweet-hearts goodbye to march off on some romantic moral crusade to free the slaves as they hummed along to the strains of “The Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

This is not to deny the very real and potent fact of political abolitionism nor the evil of slavery itself. But that is only a piece of the puzzle.

The first grand Union commander, Gen. George McLellan, explicitly stated that the Union soldiers would not fight for the slaves. Lee humbled the “Young Napoleon” on the Virginia Peninsula, even as a black Confederate sniper picked off Yankee soldiers for good measure.

Going backwards in time, after the United States banned the importation of slaves in 1808, illegal but tolerated Yankee slave ships that were operating out of ports in Connecticut, Rhode Island and Massachusetts. After 1865, Yankee merchants carried on a lucrative trade with the Sultan of Zanzibar. This unsavory despot was supplying New England and New York with ivory extracted from Africa by slaves that were literally worked to death. The reader might enjoy tapping his fingers on such ill-gotten loot as he plays Mozart on his grandfather’s piano in some luxurious maritime mansion in Newport.

Confederates can say with honesty that the Stars and Bars never flew over a slave ship. But the same cannot be said of the Stars and Stripes.

The brutal reality is that the North fought and won a war of conquest over the South. There was no way that the Northern powers would accept the loss of more than half the national territory. One section conquered and subjugated the other. Both sections were caught in the web of slavery. And the North still had to finish off the Plains Indians.

In the beginning of the conflict New York City even threatened to join the Confederacy to keep the cotton flowing. And towards the end Georgia threatened to secede from the Confederacy over conscription.

As a means to an end the North weaponized the slavery issue. And it traded the tenets of civilized warfare for those of total war. Northern soldiers raped, burned and pillaged their way through what they hypocritically regarded as their own nation. They even killed cows. Read a little bit about Sherman or the beady-eyed Sheridan to learn more, but not right before you go to sleep.

In contrast to the intellectually lazy “The Confederacy Equals Slavery” narrative, there is an exceedingly complex matrix of facts and attitudes which cannot but fascinate even as they perplex.

For example, not just whites, but also free blacks were slaveholders of blacks in America, all the way to 1865. And to keep the debate as confusing as possible, in the 1850s Virginian George Fitzhugh even argued for white chattel slavery.

Today’s schoolchildren should already know well that in the Northern mines the laborers were politically free yet economically enslaved. In our own day the creepy globalists spawning in the ideological creeks of Klaus Schwab’s World Economic Forum sloganeer about the coming socialist Great Reset in which, “You will own nothing but will be happy.” Like good slaves?

Homo homini lupus.

The historical nugget which is the thrust of this meandering essay is that, in the midst of all this fog, it is eminently defensible to maintain that our particular person of interest, Robert E. Lee, simply and categorically was not fighting for the perpetuation of the dreadful institution. He is not to be counted amongst the knaves.

In fact, by siding with the local authority of the States over a constantly self-aggrandizing central power it could be argued that Lee, wittingly or unwittingly, was partaking in an experimental end-run around the slavocrats contradictorily bellowing about their own liberty while ignoring their glaring moral flaws. Had the great Confederate chieftain Lee gotten his way, the slaves would have been well on the road to emancipation. And the slaveholders would have gotten the overdue constitutional chiropractic adjustment to realign their own notions of authentic freedom.

But when the central government utterly vanquished the concept of local State authority it set the stage for an insatiable thirst for power and control. Currently, it certainly appears to be attempting a more total and far-reaching kind of modern slavery under the banner of “Equality (or Equity) for all slaves,” or something like that.

Is this viewpoint an admixture of history with hagiography? Let the reader decide.

But knowing the essential fact of Lee’s attitude toward freeing the slaves certainly helps one to put into perspective the wrongheaded, benighted outrage that precipitated the attack on his Richmond monument. Lee was, forsooth, that City’s tragically misunderstood icon of freedom. And the fools tore him down! But let us not be naïve, for the children of Marx are expert at mobilizing the impetuous.

That is what this writer contends as having transpired in Richmond City from 2020 to 2021, viz., a neo-Marxist cultural revolution took place which was designed to destroy the natural order of society, and the human person in consequence. The orchestrators of the attack on America managed to commingle social justice for blacks with the gender ideology. And it was morally repulsive to witness. The Yankee abolitionists of the 19 th Century themselves would have recoiled at the notion that their movement had anything to do with something as diabolical as puberty blocking hormones. But the graffiti about the Lee monument boldly proclaimed the warped

anthropological heresy.

In any event, at Appomattox Courthouse the world was presented with the ironic spectacle of the Confederate General Lee (who was not a slaveholder) surrendering to the Federal General Grant (whose own wife at that precise moment owned a slave named Julia).

Even after the surrender, the North begrudgingly respected and the South weepingly venerated Lee so much that the Radical Republicans were fearful of his possible accession to the presidency of the re-United States in 1868, and they dragged the man before Senate hearings to further his ruination. Yet Grant, to his credit, would brook no talk of Lee’s arrest or dishonoring.

But to the mob gathered about Lee’s statue on September 7, 2021, waiting with bated breath for the final act of the tragedy, the historical record apparently mattered little. Cruelly, as it was opposing even the perceived and threatening memory of Lee, American Marxism repackaged for the 21st Century had duped its thralls into absorbing a highly metastasized form of an even more absolute slavery that is menacing the entirety of America.

I sought, on that bright sunny September day, to find some redemptive value to the quite disturbing spectacle before my eyes. It suddenly came to me in a flash as I gazed upon the image atop its pedestal. The vile, caked layers of venom that defiled the massive pedestal, which climbed up like a poisonous vine from the depths, were halted just below the portion from which Lee’s image arose to the skies.

The symbolism was inescapable. Lee’s statue was besieged. The entrenchments were dug close and encircled him. But the figure of the man himself stood gleaming in the sunlight, noble, unsullied and dignified to the end. The vigilantism of the frustrated mob had not even touched Lee in his symbolic, statuesque grandeur.

The tearing down of his iconic monument the next day, on September 8, 2021, was only brought about, as was his surrender of April 9, 1865, by “overwhelming numerical and material forces.” But this cultural and historical violation did not lessen the superiority of the principles of political subsidiarity, limited central government and personal honor for which Lee essentially stood in life as in death.

In this deeper, more timeless sense, Robert E. Lee might be regarded as the true victor of the latter-day Battle of Richmond.

Don Antonio San Pasquale is a Catholic priest who witnessed the Richmond events in 2020 and 2021.

Featured: “Robert Edward Lee,” nu John Adams Elder; painted in 1876.