Positioning the Problem

If there is a dilemma that remains unresolved, it is that of the relationship of Catholicism to liberal democracy. This dilemma is based on two fundamental factors. While, for many centuries, Catholicism has developed its attachment to the concept of the person, liberal democracy is intrinsically linked to the philosophical concept of the individual. Moreover, upstream of this divergence are two concepts that are opposite in nature. The Catholic one is rooted in the political philosophy of Aristotle, according to which man is a social animal, a postulate taken up by Thomas Aquinas in the 13th century. The liberal one is based on the idea that men (individuals) do not live politically at first, but in a state of nature and war with each or against each (Hobbes), or in a positive state of nature but destined to degrade (Locke); hence the need to establish a contract between individuals in order to access political life. In other words, whereas in the first case, political life is immediately qualified positively; in the second it is qualified positively only by necessity.

This is what Pope Leo XIII opposed at the end of the nineteenth century and what the Second Vatican Council continues to oppose. But the political teaching of the Roman Magisterium has evolved nonetheless. This is what I would like to examine, by first restating some of the major points of the encyclical Immortale Dei (on the Christian constitution of states) and then restating those of Gaudium et spes (the Church in the Modern World) of the Second Vatican Council. Yet from one to the other of these two teachings of the Roman Magisterium, the historical misunderstanding of what democracy means persists.

The Encyclical Immortale Dei (1885): A Response to Liberal Democracy

In the context of the publication of Immortale Dei, four major facts should be brought to mind. Leo XIII was the first pope who never had a temporal state; he was grappling with the Kulturkampf in Germany and with the secularization of school education in France. Finally, the encyclical is contemporary with the rise of socialism. This is why the political teaching of Leo XIII was completed in 1891 by his social teaching; these two doctrinal bodies being the two legs without which the Catholic Church could not walk in the modern world, which was less and less favorable to it at the end of the 19th century. Five aspects of Leo XIII’s thinking in the encyclical Immortale Dei are evident. All of them oppose the fundamental principles of liberal democracy, by recourse to the political philosophy of Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas, according to which man, a naturally political animal, seeks the common good with his fellow human beings.

But this naturalistic principle had to be complemented by New Testament teaching that all political power comes from God, regardless of the form of the regime. This is the central problem. The modern (liberal) world, anxious for its autonomy from any religious foundation, was turning away from God, the theological and political principle that had organized Christian Europe for centuries. The result for Leo XIII was the need for public worship and the opposition to religious freedom. Leo XIII rejected it because it would lead to the collapse of public worship, which can only be given to the one true God and thanks to which the solid and necessary unity of the political order is guaranteed. There is no legitimate authority without the support of truth, and no viable society without it; but there is also no public worship without recognition of the true God, of whom the Church is the depository through its spiritual leaders, the pope being the head.

The same is true of freedom. The Christian order, which comes from God, does not dispute its relevance, but it is not valid unto itself, being an “element of perfection for man,” which “must be applied to what is true and what is good.” Finally, the representative system of liberal democracy is at most evoked, and in a negative way with the explicit fear that it generates “the right to riot” because of its correlative link with freedom of opinion. Much more important for Leo XIII was the political status accorded to “the people” who have “their greater or lesser share in government,” which share is “not only a benefit, but a duty for citizens.” However, nothing is said about the concrete procedure by which the people take “their share in government.” This matter of democracy in magisterial teaching came back on the agenda at the Second Vatican Council with Gaudium et spes. This raises the question—did the Second Vatican Council embrace liberal democracy, or does it not rather propose a Catholic understanding of democracy?

Gaudium et spes: A Liberal or a Catholic Conception of Democracy?

In the wake of the last world war and the two totalitarian regimes of the Nazis and the Soviets, the Roman Magisterium has undoubtedly evolved; but it has not abandoned its fundamental concepts, especially those of the search for the common good and the political authority required to achieve it. What has changed is that the correlation between the common good and political authority combines the “free will” of citizens to choose their leaders with the traditional idea that “the political community and public authority have their foundation in human nature and through it are subject to an order fixed by God.”

It should be noted, then, that from Leo XIII to Vatican II, there is great continuity in magisterial teaching. It is, however, within this tradition that Gaudium et spes accredits the principle of democracy as the legal functioning of the political community, something that Leo XIII could not accept in such a clear-cut manner. Nevertheless, just as Leo XIII did not want to rally French Catholics to the Republic for philosophical and theological reasons, Vatican II did not advocate rallying to liberal democracy for the same reasons. The Church is therefore faithful to her vision of man in society, especially since the reception of the thought of Thomas Aquinas, while reconsidering it in the light of the norms of liberal democracy. The latter is acceptable, provided that it is rooted in an order of nature that is in every respect opposed to the modern conception of nature of the 17th and 18th centuries.

In other words, Vatican II gives itself the theoretical instruments to think about a Catholic conception of democracy, while accepting in a practical way the achievements of liberalism (freedom of association, of assembly, etc.). Let us also note the conciliation of a Catholic conception of democracy with liberal achievements. This is explicitly demonstrated by the “guarantee of human rights” and the rejection of “all political forms… which impede civil or religious liberty;” or the idea that a political authority which contravenes the common good, “citizens” must “defend their rights… respecting the limits set by the natural law and the law of the Gospel.” This Catholic conception of democracy is corroborated by the defense of religious liberty. Whereas Leo XIII conceded only the tolerance of religions, Gaudium et spes calls for “the right to express personal opinions and to profess one’s religion in private and in public.” It is perhaps this reconciliation that gives the false impression that democracy as defended in Gaudium et spes is basically the Catholic version of liberal democracy. Hence the continuation of the historical misunderstanding that has been simmering since the end of the Council and which is now coming to light through recent societal developments.

Liberal democracy and the Catholic understanding of democracy: a historical misunderstanding that is still relevant today

With Gaudium et spes, the Second Vatican Council undeniably made a great leap forward in allowing Catholics to have their own conception of democracy, not thought of as a counter-society, but as a means of acclimatizing liberal democracy to Catholic culture and vice versa. But what could have been a beautiful symphony did not achieve its goal. Either Catholics secularized themselves into the liberal democratic mold by adopting the rhetoric of humanistic values. Or they sought a self-referential Catholic anchor that looks more like a Christian neo-democracy than a Catholic conception of democracy. Yet it is this ambition that must be pursued so that Catholics can spearhead a revitalized conception of democracy which needs it most.

Father Bernard Bourdin o.p. published, with Philippe Iribarne, La nation, une ressource d’avenir. The nation, a point of balance between the universal and the rooted. This article appears through the generosity of La Nef.

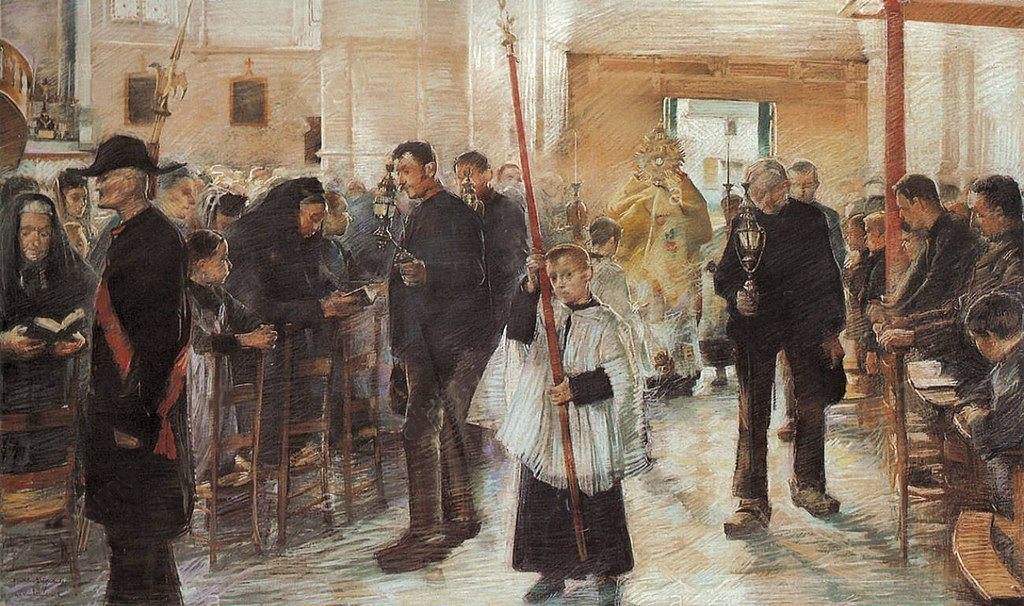

Featured image: “Procession in church,” by Guillaume van Strydonck; painted ca. 1900.