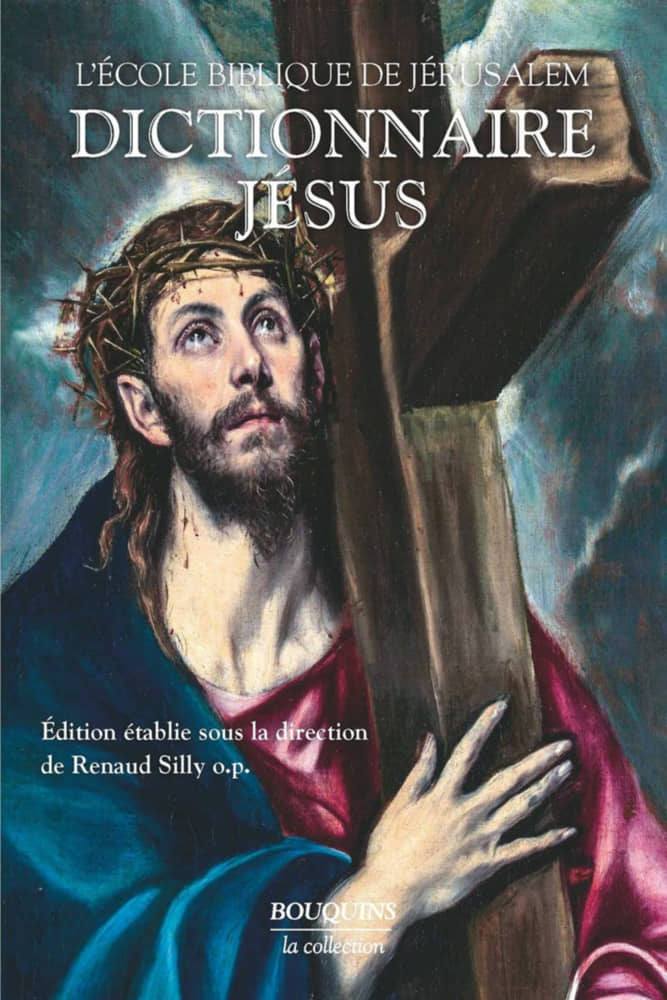

It is a great honor to present this conversation with Brother Renaud Silly, OP, historian and theologian, who speaks about the Dictionnaire Jésus (the Jesus Dictionary), the major work recently published by the École Biblique de Jérusalem and Éditions Bouquins. This Dictionary which makes available the current state of knowledge about Jesus, drawing upon all necessary scientific, theological, and philosophical areas of expertise.

The Dictionary is an impressive work (comprising some 1300 pages), but one that is also highly accessible, for it does not neglect the needs of the lay reader who is well rewarded by the depth and erudition. Father Silly oversaw the work, as the director of the entire project, and he speaks with Christophe Geffroy, the publisher of La Nef magazine, through whose courtesy this article is here translated.

Christophe Geffroy (CG): How did the idea of the Jesus Dictionary come about? What was your goal, and what was your working methodology?

Father Renaud Silly (RS): The person who had the idea was the director of Bouquins, Mr. Jean-Luc Barré [the publisher]. We had previously published Bossuet in his collection, and this inspired him to call upon us to produce the Dictionary. He gave us carte blanche, without imposing any particular angle or contributors.

As for the École Biblique, the immense wealth of its recent research was just waiting to be made accessible to the general educated public. In the middle of the last decade, the success of certain books, ill-informed we believe, made us feel the need for a work that spans the entire spectrum—those who have been given the capacity to work directly on the sources (the “scholars”) have a moral duty to guarantee the dissemination of their work to those who do not possess it. Otherwise, we fall into the opposite trap of popularization and autarkic specialization. You likely will recognize in this way of thinking about the relationship to knowledge an echo of the ancient Dominican motto “contemplari et contemplata aliis tradere” (“contemplate and teach others”).

CG: This Dictionary was conceived in “a scientific spirit,” we read on the back cover. What does this mean?

RS: “Scientific” means many things, from the experimental method of the hard sciences to the discussion of all contradictory propositions in the human sciences, already practiced by Saints Thomas Aquinas and Albert the Great. To be readable, the Dictionary could not afford either. On the other hand, it deserves the term in the sense that it is directly linked to a scientific project of the École Biblique de Jérusalem: La Bible en ses Traditions (The Bible in its Traditions), under the direction of Brother Olivier-Thomas Venard, OP.

Sacred Scripture exists in three dimensions: it has a past—the conditions of its composition, a present—the text with all its refinements, and a future—its impact on culture, morality, etc. To understand it, it is therefore necessary to combine knowledge of the environments that produced it, literary methods of analysis, and to be attentive to its reception, in particular that for which it is an authority. The Bible in its Traditions is a method of global understanding of Scripture, without exclusivity or reductionism. It is a way of letting revelation breathe in a space that is appropriate to it. Who can contest the scientific nature of such an approach?

CG: Is it compatible to be in this “scientific spirit” and therefore open to new discoveries and at the same time faithful to the faith and to the teaching of the Church whatever happens? How does the scientist who is also a man of faith react when a discovery seems to go against the teaching of the faith?

RS: In faith, certainty is God who is at once the source, the cause and the object of the knowledge that faith possesses of him. The uncertainty lies in the assent we give to him—in other words, in not wanting to believe in God, even though He is the end of our understanding (cf. Thomas Aquinas, ii-iiae q.2 a.1 resp.). If faith saves, it is because it is a voluntary act. The vices that can thwart the operation of the will are, however, manifold: laziness, negligence, superstition, pride, to name but a few.

In short, sympathy for science, hard work, the breadth of knowledge cannot substitute for the adhesion by which the soul submits to the truth of God who reveals himself freely to it. This is the formal reason for faith as a theological virtue. In short, the scholar, like all other Christians, has no other alternative for remaining on the right path than to cultivate virtue.

But we must hasten to add how liberating the supernatural act of faith is for the scholar, for it relieves him of the need to search by force for a proof of faith that the texts, even and especially the sacred ones, will never offer him. The Lutheran theory of sola scriptura obliges one to solicit the texts, to make them say what they do not say. Since fiction cannot hold for long, sola scriptura has caused dogma to fall one after the other. And in return, it is the Bible itself that has become a source of uncertainty and doubt. As Father Lagrange wrote, “It is from [the Reformation] that the study of the Bible dates, not the study of the Bible, but rather the doubt about the Bible.”

CG: You have not sought to take a new, but a renewed, look at Jesus. What do you mean by this?

RS: In 1980, a tomb on the outskirts of Jerusalem was interpreted as that of Jesus. In 2002, an ossuary was presented as that of James, the “brother of the Lord,” which would have confirmed the authenticity of the 1980 tomb. In 2006, a Gnostic gospel “of Judas” appeared, according to which Jesus himself asked the traitor to hand him over. In 2012, in the Gospel of the Wife of Jesus, the master presents Mary Magdalene as his wife. All of these “discoveries” turned out to be forgeries or misinterpretations of authentic texts. The ephemeral excitement that surrounded these publications shows our imaginary and infantile relationship to reality, which makes us give in to the craving for novelty (cf. 2 Tim 4:3-4).

But there is no scoop to be made about Jesus. In faith we know all we need to know about him. As far as authentic knowledge is concerned, made up of meditation, of going deeper, of the patient dwelling of the truth deposited in us—this on the other hand is always in need of renewal. The Word came to “dwell with his own” (Jn 1:5); He is therefore there, in the midst, but it is we who are absent: “you were within me, but I was outside myself, and it was in this outside that I sought you” (St. Augustine, Confessions, x, xxvii, 38).

There is always a need to renew one’s knowledge in order to free oneself from hasty patterns of thought, from the conviction—certainly false—that one has done all the work of the Gospel and has nothing to expect from it. This must be done in the school of the great texts, but also of the humble reality unearthed by archaeology and the related sciences.

A few years ago, stone jars were discovered at Cana (cf. Jn 2:6)! They are probably not those of the miracle, but it shows that this village was populated by very observant Jews, the very milieu of Jesus. Study is an asceticism, surely the greatest asceticism there is! Has the Latin Church nurtured greater ascetics than St. Jerome or St. Thomas, those hard workers? But for those who devote themselves to this effort, the Word is always new (cf. Rev 21:5).

CG: In making this Dictionary, which points were the most difficult to synthesize? And what are the most difficult topics to resolve from the point of view of faith?

RS: The Resurrection of Jesus, to which we wanted to give a place in proportion to its importance. The very fact of the Resurrection is not recounted anywhere [outside the Gospels]—because there were no outside witnesses; and the evangelists did not embroider wonderful stories when they did not know! So, we have to fall back on credible witnesses of the Risen One, since we did not see him rise. But this only shifts the problem: they are women, whose testimony has little legal value! One recalls the misogyny of a Renan who described the testimony of Mary Magdalene on Easter morning as follows: “Divine power of love! Sacred moments when the passion of a hallucinated woman offered the world a resurrected God!”

Let us add to this that the Resurrection is, by definition, impossible to describe since it tells of the passage (the “passover”) of Jesus to a new Creation which we cannot experience; that the mode of the Resurrection of Jesus does not correspond to that foreseen by the prophets of Israel—teaching rather a general and simultaneous resurrection. Yet the resurrection constitutes the intimate heart of the proclamation of Christian faith and hope (cf. 1 Cor 15:14). It is impossible to ignore it without betraying the Gospel.

We are left amazed by the simplicity of the means with which the sacred authors overcome this immense difficulty. The resurrection narratives are the least retouched of all the Gospels. They are delivered to us almost in their raw state. They ask us to let ourselves be measured by the event and the word that tells it. To accept it is to grow in faith, and thus to rise a little with Christ. The resurrection narratives form the synthesis and the summit of the Gospel’s power of conviction. They invite us to reread all the teachings of Jesus as seeds that make life sprout where there was nothing.

CG: It is common to distinguish between the Jesus of history and the Jesus of faith. What do you think of this approach? And is faith still credible in the light of current scientific knowledge?

RS: The expression you quote belongs to the genre of “thinking” (sorry to abuse this beautiful word) by slogan. It is based on the conviction that the “faith” accumulated representations of Jesus, which would have satisfied certain requirements of the religious spirit, as the Church grew outside its original environment.

The Jesus of faith therefore becomes the sum of the answers demanded by the new Christians according to their cultural situation. The divinity of Christ would be the most visible of these borrowed identities, developed in contact with Hellenistic populations familiar with divinized heroes. Hence the need to peel away, by means of criticism, the “Jesus of history” from the various accretions that mask him. Alain de Benoist’s book illustrates this method and shows its limit via the absurd. In tearing off the tunic of Nessus which would be the Jesus of faith, one realizes that the layers are so well integrated with the object studied that the object loses its skin, flesh and bones. In the end, there is nothing left. One wonders how this so-called “Jesus of history,” so insignificant, could have left such a trace.

But this distinction is wrong. The Jesus of faith is nothing other than the trace left by the Jesus of history, the sum of his impact, as it were. Jesus initiates recourse to the testimony of the prophets to speak of him (Mk 12:35-37); he sends out on mission (Mk 6:6-13); he takes care to establish an authentic transmission of his words and actions (Mk 8:18-21); he projects his disciples into a time when they will have to keep his memory in order to understand (Jn 13:7); he institutes the signs that will give body and shape to this memory, especially the Eucharist (cf. Lk 22:19). Between the Jesus of history and the Christ of faith, there is no unbridgeable gap.

CG: The Bible is undoubtedly the most examined work in the world, dissected from every possible angle, especially since the development of the historical-critical methods. Does the Bible emerge strengthened from these examinations and analyses; or, on the contrary, weakened in its credibility?

RS: Science can be a very violent thing. Laboratory experiments, which give rise to many ethical problems, bear witness to this. There is a certain science which, legislating on phenomena, imposes on them extrinsic grids of analysis which destroy them. One thinks of the Duke of Chevreuse inflicting a thousand tortures on dogs or cats to try to prove that their cries were caused by the shaking of small springs, in accordance with the Cartesian theory of animal-machines.

The undivided domination of the hard sciences in the Western noosphere has resulted in the increased use of intrusive criteria on the Bible. Christians who believe in supernatural revelation do not defend it by subjecting it to these same criteria. Biblical fundamentalism, so regularly condemned by the pontiffs, must appear to us for what it is: a complicity with the dissolution of the Bible by historical methods. Moreover, it is futile: by leaving the choice of weapons and terrain to the adversary, we expose ourselves to certain defeat. But to write an ancient history of Israel by following the biblical account is to provoke the derisio infidelium.

The Bible is strengthened if one analyzes it according to its own criteria, those of ancient literary genres; and if one makes the effort to understand its language, which is often disconcerting. It is thus a precious source for the historian. But the Bible is much more than that—a matrix of culture, religion, morality, philosophy and dogma. On this contemplative domain, that of the spirit, aggressive science has little hold.

CG: The literature on the Bible is so vast now that it is impossible for the educated man of today to know it all. How can you find your way around, and how can the researcher, such as you, take into account all that is published seriously on the Bible?

RS: Give preference to authors who do not simply compile the results of others’ research, but have direct access to the sources and are able to discuss them. The others do not know what they are talking about. Exclude anything that practices methodical deconstruction—its conclusions have no solidity; they fluctuate according to fashion.

CG: Many people think that the Bible is nothing but a series of myths far removed from real history and that it often relates stories that they consider far-fetched and impossible—the fall in the Garden of Eden, the flood, or the crossing of the Red Sea, for example. How should the Bible be read? Are there several levels of reading? And how can one distinguish between what belongs to history, to theological teaching or indeed to myth?

RS: Neither the flood, nor the stories of the fall, or the tower of Babel can be proven “scientifically.” Those who claim otherwise are lying or mistaken. Their historicity has nothing to do with the historiographical models claimed by the evangelists, or the deuteronomistic historian (Deuteronomy), or the priestly models (Chronicles, Ezra-Nehemiah). All of these follow very rigorous paradigms—though different from modern ones. Did the Bible in Gen 1-11 collect myths? If one understands this term as a divine revelation about the origin, inaccessible de jure to human observation, then why not. But this must be seriously corrected—because they are very different from the myths vilified by the philosophers.

CG: Our European countries of ancient Christianity, with rare exceptions, such as Poland, have evacuated the question of God, so that the number of truly convinced Christians has become a tiny minority—our contemporaries are much more ignorant of Jesus than hostile. How can we make them rediscover this Jesus who saved the world?

RS: Like Christ, I don’t believe in strategies, tactics or structures of Christianity. Nor do I believe in sociology to prophesy to us whether Christians will be many or few. All that is thinking according to the world.

But I believe that the power of conviction of the Gospel remains intact, if it is preached for what it is—the teaching of the Master who makes faith germinate in souls eager for truth, who tears his disciples away from a world for which he himself has not prayed (cf. Jn 17:9), to which no promise of eternity is attached (cf. Mk 13:31).

The disciple of Christ is the one who receives in his heart this prayer of Bossuet: “O Jesus, I come to you to make this Passover in your company. I want to pass with you from the world to your Father, whom you wanted to be mine. ‘The world is passing away’ (1 Jn 2:17) says your apostle. ‘The face of this world is passing away’ (1 Cor 7:31). But I do not want to pass with the world, I want to pass to your Father. This is the journey I have to make. I want to make it with you…. O my savior, receive your traveler. I am ready. I do not care about anything. I want to pass with you from this world to your Father” (Meditations on the Gospel, “The Last Supper”, Part I, Day 2).

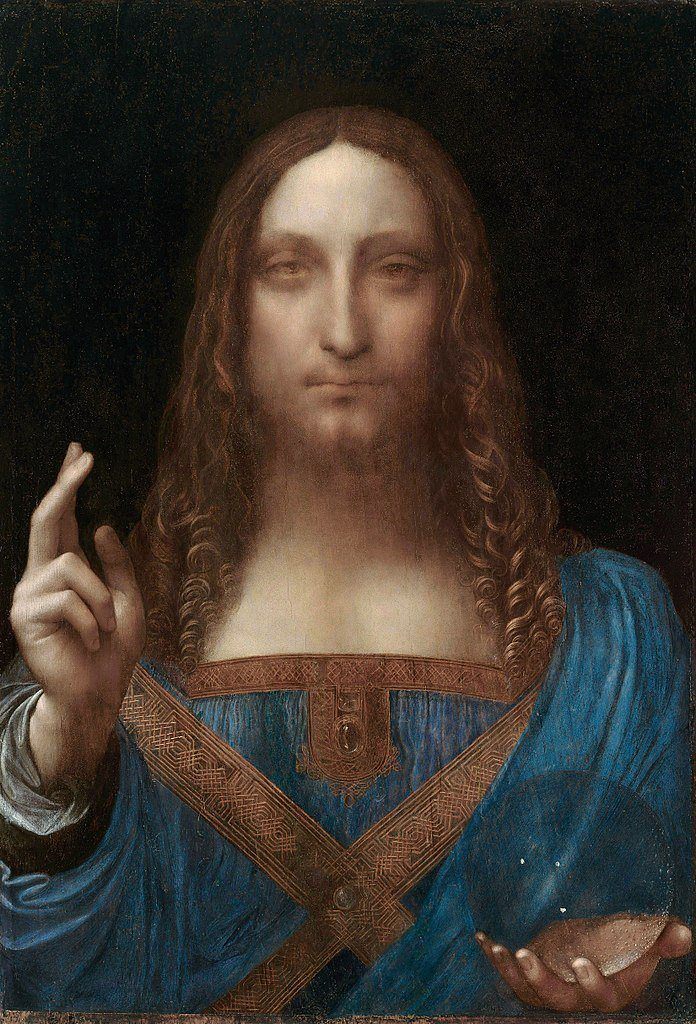

Featured image: “Salvator Mundi,” by Leonardo da Vinci, painted ca. 1500.