The Battle of Berlin was the final large-scale military operation to take place in Europe during World War II. The British and American allies did not participate in this offensive, leaving the Soviet army to conquer the city alone.

The Battle of Berlin was one of the largest battles in human history. It began on April 16 in the outskirts of the city. By April 25, Soviet troops had entered the Third Reich’s capital. About 3.5 million soldiers from both sides participated in the fight with more than 50,000 weapons and 10,000 tanks.

Soviet troops stormed Berlin while the rest of the Allied army remained more than 100 kilometers outside the German capital. In 1943, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt declared that “the U.S. must obtain Berlin.”

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill agreed that the Nazi capital must not fall into Soviet hands. However, in the spring of 1945, these Allied forces did not make any effort to take possession of the city. British historian John Fuller called it “one of the strangest decisions ever made in military history.”

However, this decision had its motives. In an interview with RBTH, Russian historian Andrei Soyustov said that there were at least two reasons for this decision.

First, according to preliminary agreements, including the accords made in Yalta, Berlin was located in the zone of Soviet military operations. The demarcation line between the USSR and the other Allied forces went along the Elbe River. “Rushing into Berlin for the sake of status, could have, at minimum, backfired and may have resulted in a USSR decision not to fight against Japan,” explains the historian.

The second reason for not storming the giant urban center was that the Allies had been fraught with casualties as the end of the war approached. In the period between the Normandy landing and April 1945 the Allies “were able to avoid storming large cities,” Soyustov notes.

Soviet casualties in the Battle of Berlin were indeed very high with 80,000 injured and at least 20,000 killed. The German side suffered just as many losses.

Berlin was captured by Soviet troops on three fronts. The most difficult task fell to the soldiers from the First Belarus Front, commanded by Georgy Zhukov, who had to charge the well-fortified German position in Seelow Heights on the outskirts of the city.

The attack began during the night of April 16 with an unprecedentedly powerful and coordinated artillery barrage. Then, without waiting for morning, tanks entered the battle supported by the infantry.

The offensive was conducted with the help of floodlights, which were set up behind the advancing troops. Even with the use of this clever this tactic, several days were needed to seize Seelow Heights.

Initially, almost one million German servicemen were concentrated around Berlin. However, they were met by a Soviet force that was 2.5 times greater. At the very beginning of the Berlin operation, Soviet troops succeeded in cutting off the majority of the German units from the city.

Due to this, the Soviet Army encountered only a few hundred thousand German soldiers in Berlin itself, including the Volkssturm (the militia) and the Hitler Youth. There were also many SS units from different European countries.

Hitler’s troops worked desperately to defend themselves with two lines of defense organized in Berlin. Many homes were equipped with bunkers and these houses, with their thick walls, became impregnable strongholds.

Of particular danger for the advancing Soviet troops were the anti-tank weapons, bazookas and hand grenades since Soviet forces were heavily reliant on the use of armored vehicles during the attack. In this environment of urban warfare, many tanks were destroyed.

Following the war, commanders of the Soviet operation were often criticized for relying so heavily on the use of armored vehicles.

However, as emphasized by Soyustov, in such conditions the use of tanks was justified: “Thanks to the heavy use of armored vehicles, the Soviet army was able to create a very mobile unit of support for the advancing troops, which helped them break through the barricades into the city center.”

The tactics used in the Battle of Berlin built on experience from the Battle of Stalingrad. The Soviet troops established special assault units, in which tanks played a critical role.

Typically, maneuvers were carried out in the following manner: The infantry moved along both sides of the street, checking the windows on both sides, to identify obstacles that were dangerous for the vehicles, such as camouflaged weapons, barricades and tanks embedded in the ground.

If the troops noticed such impediments up ahead, the Soviet infantry would wait for the arrival of their self-propelled tanks and self-propelled howitzers, known as “Stalin’s sledgehammer.”

Once this support arrived, the armored vehicles would work to destroy German fortifications at point-blank range. However, there were situations where the infantry could not keep up with the armored vehicles and consequently, the tanks were isolated from their cover and became easy prey for the German anti-tank weapons and artillery.

The culmination of the offensive on Berlin was the battle for the Reichstag, the German parliament building. At the time, it was the highest building in the city center and its capture had symbolic significance.

The first attempt to seize the Reichstag on April 27 failed and the fight continued for four more days. The turning point occurred on April 29 as Soviet troops took possession of the fortified Interior Ministry building, which occupied an entire block. The Soviets finally captured the Reichstag on the evening of April 30.

Early in the morning of May 1, the flag of the 150th Rifle division was raised over the building. This was later referred to as the Banner of Victory.

On April 30, Adolf Hitler committed suicide in his bunker. Until the last moment, Hitler had been hoping that troops from other parts of Germany would come to his aid in Berlin, but this did not happen. The Berlin troops surrendered on May 2.

Calculating the losses involved in the Battle of Berlin at the end of such a bloody war, some historians doubt whether the Soviet attack of the city was necessary.

In the opinion of historian and writer Yuri Zhukov, after the Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe river, surrounding the German units in Berlin, it was possible to do without the offensive on the Nazi capital.

“Georgy Zhukov… could have just tightened the blockade circle on an hourly basis… But for an entire week, he mercilessly sacrificed thousands of Soviet soldiers… He obtained the surrender of the Berlin garrison on May 2. But if this capitulation had occurred not on May 2 but, let’s say, on the 6th or the 7th, tens of thousands of our soldiers would have been saved,” Zhukov continues.

However, there are other opinions that contradict this view. Some researchers say that if the Soviet troops had just besieged the city, they would have lost the strategic initiative to the Germans.

Nazi attempts to break the blockade from the inside and outside would have resulted in just as many losses for the Soviet Army as the attack, claims Soyustov. It is also not clear how long such a blockade would have lasted.

Soyustov also says that delaying the Berlin operation could have resulted in political problems between the Allied forces.

It is no secret that towards the end of the war the Third Reich’s representatives tried to negotiate a separate peace deal with the Americans and British forces. “In these circumstances, no one would have been able to predict how a blockade of Berlin would have developed,” Soyustov is convinced.

Alexey Timofeychev writes for Russia Beyond.

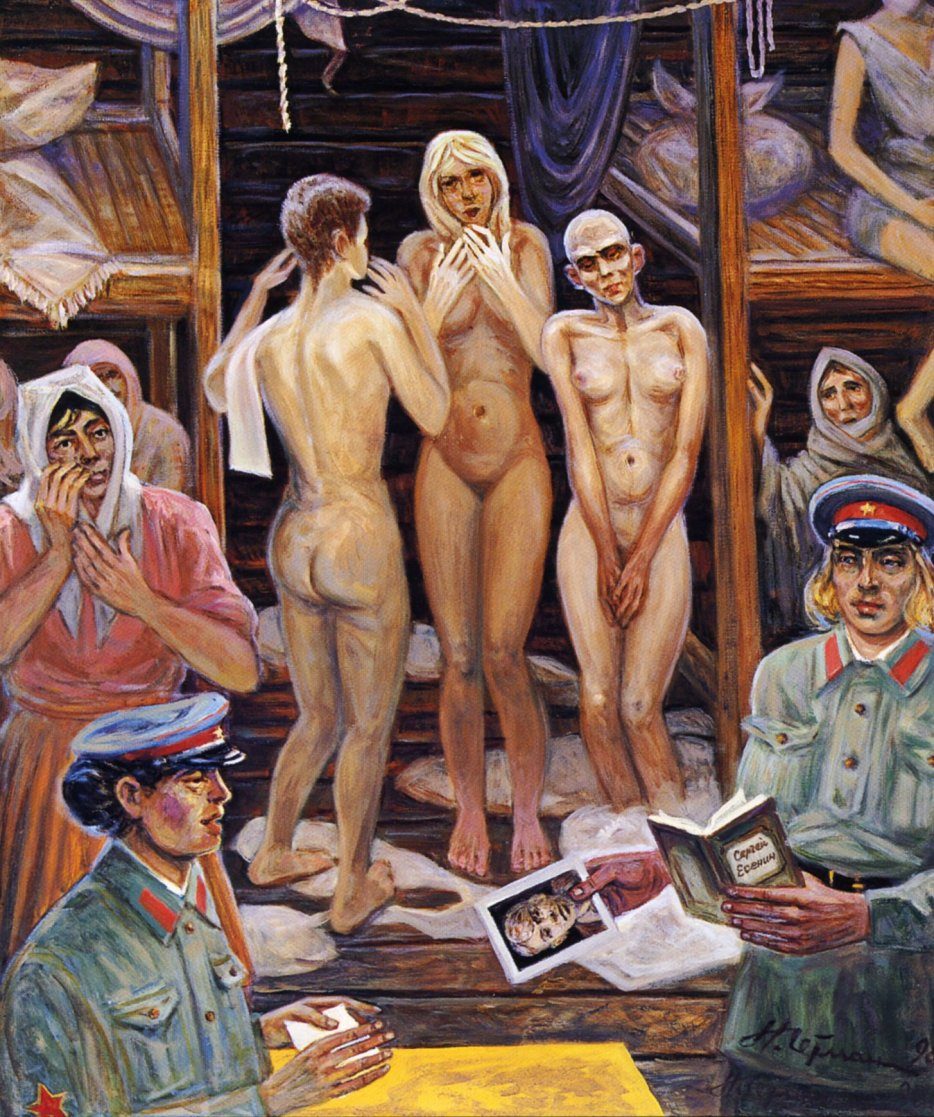

The photo shows, “The Storming of the Reichstag by the Red Army, 1945,” part of a diorama in the German-Russian Museum in Berlin-Karlshorst.