The slow but eventual devolution of civilization is a difficult topic to discuss, since it runs counter to the usual human reaction which prefers to see the future in a rosier fashion – after all, our children and grandchildren have to live in it, and we would hardly want them to manage their way through Hell.

But ideas have consequences, and if we are to imagine the devolution of the West, we must turn to its true origins, the Greeks, and we must read again the words of the man who invented history, namely, Herodotus.

But first, let us consider some of the more prevalent (perhaps a better term is, “notorious”) ideas which now beset the West in these early years of the twenty-first century – ideas which the West seems to want to escape, but will not, no matter the consequences they might (or will) bring.

The most pressing is the Cult of Presentism, that deep-seated belief that the Western past is forever wrong, and because it was wrong, the past is responsible for bringing endless misery into the world.

This is finding expression in the rising and trendy racism of being anti-white.

Then, there’s the continuous self-abnegation via multiculturalism, where any hellish culture of the world is given equivalence and compatibility to the West, well, because the West has been terrible evil in the past (cue the role call of the “Crimes of the West”).

All this makes Presentism a rather peculiar beast. Why peculiar? Well, because it aligns rather perfectly with an ideology now promoted as the replacement of Christianity, namely, Islam.

At the core of Islam lies a version of Presentism, namely, the doctrine of Jahalat, or more commonly, Jahiliyyah, the root meaning of which is “ignorance.”

Let’s ponder this for a while.

In Islam, Jahiliyyah is understood in two ways, one references history, and the second points to the quality of true civilization.

Historically, Jahiliyyah means the world before Islam, which is regarded as a time of darkness and utter barbarity because it was wrapped in profound ignorance, since the past lacked both enlightenment and progress (the doctrinal term in Islam is “ilm” or “truth and wisdom”). Only Islam possesses ilm and holds it its duty to bring this ilm to the world.

Ilm is encoded perfectly in Shariah (divine law by which all humanity is supposed to live). The ilm of Shariah alone can establish a proper civilization and a proper culture – which means that Shariah is the ultimate destiny of all humanity.

Thus, anything before Islam is nothing but a perversion of the truth and worth nothing at all – hence the ease with which a sledgehammer can be swung in a museum.

The past is useless because it has no intrinsic worth whatsoever – because it lacks Shariah. The Islamic present is perfection because it has Shariah.

In other words, only Shariah is progress.

As well, Jahiliyyah opposes another Islamic quality (which builds civilization itself), namely, hilm, which is best rendered as, “cultured,” or “civilized.”

Thus, Islam brings ilm to a barbaric and depraved world, and this gives into human possession hilm, which in turn fashions the perfected man, enlightened and made progressive by ilm (the true and therefore only wisdom).

Hilm itself bestows particular virtues, namely, courage, strength and moral character, all of which are given to a man once he has the ilm to follow Shariah properly.

Further, in Jahiliyyah humanity can be nothing other than savage, barbarous and ignorant.

Since Allah does not come down to govern the world himself, he sends his representative, the Shariah, to govern the world as he would govern it himself. This makes it imperative for all humanity to submit to the Shariah, because all humanity belongs to Allah.

This also points to another Islamic doctrine which holds that all humans are born Muslim; it is only the influence pf Jahiliyyah which lures them away from the truth of Shariah and changes them into infidels. Thus, it is the job of each Muslim to guide all of humanity to its proper destiny.

Notice the curious and important similarity with what Presentism holds to be true – that the past is forever flawed because it is backwards and ignorant, even barbaric, because it did not have progress. This progress is true enlightenment.

As well, Presentism declares the present to contain all the truths that humanity will ever need once and for all.

So, Presentism operates in the same way as Shariah, since both seek to build the better human being.

This brings us back to Herodotus, whose insights prove both Shariah and Presentism wrong, for both claim to be better than the past, but they cannot establish themselves as morally superior to the past.

Morality is a quality of virtue which cannot come about by submission to legality (Shariah), let alone by more efficient technology (Presentism).

Laws and gadgetry are meaningless without virtue. But what about hilm, is that not also about moral virtue? No, because hilm is achieved by way of ilm, which doctrinally is only possible through submission to Shariah.

But is “submission” the proper condition for virtue? Again, no, for to submit is to deny the self and acquiesce or “blend in.” Conformity is the public face of selfishness, because it is obedience to ensure social gain.

To stay silent when the individual will is being denied is also selfishness. Both Presentism and Shariah require such obedience and such denial.

Therefore, conformity cannot be virtuous, because it means denying the individual will.

Rather, virtue comes about when the individual will is pushed to imitate a transcendent model – and if we in society work towards perfecting individual virtue, only then can society and civilization become free of hubris – which Herodotus pinpoints as the “dynamite” which blows civilization up.

Indeed, both Shaiah and Presentism promote hubris, because both demand the complete rejection of the past.

When Herodotus considers why civilizations fall, even mighty ones, he does not veer into materialist causes of economics, politics, or social “forces.”

Rather, since he rightly understands history to be circular – not that it repeats itself, but that it occurs in repeating patterns – he points to human beings as the authors of their own grandeur and their own demise.

Thus, it is the moral character of the people living in a culture which makes their world survive or fail.

For Herodotus, then, civilizations fall because of hubris, which is moral deficiency. The proper translation, from the Greek, of “hubris” is not simply “excessive pride,” but really “outrageous selfishness.”

Hubris, as Theognis reminds us, leads to two consequences – kerdos (extreme selfishness) and koros (insatiability). Neither can lead to virtue.

In effect, both Presentism and Shariah are forms of hubris, in that they are meant to satisfy and perfect life lived in an unchanging present.

And yet, the past is also memory, and it is memory alone which makes us human. Thus, both Presentism and Shariah are anti-human because they deny the past, which is memory, for memory alone can define civilization as the content of its people’s virtue.

To destroy the past is to destroy virtue itself. In that both Presentism and Shariah are complicit.

It was Thomas Paine who observed, “When we are planning for posterity, we ought to remember, that virtue is not hereditary.”

When we defend the past, we are defending memory certainly, but more importantly we are defending virtue, which is the moral fabric of our western civilization.

If we abandon our morality (which has now become our hubris), then perhaps it is better that we fall and disappear – for we will then have squandered the great moral legacy given to us to nurture and then pass on to future generations?

And it is the fruits of this morality that we daily – and thoughtlessly – still enjoy.

Now, are we truly good husbandmen of virtue? That is the question each must answer, after we have deeply examined the quality and character of our individual virtue.

Democracy can only work for a moral people – and that morality has to be the right kind, namely, the Judeo-Christian one, which is germane to the West. Otherwise, there is only hubris.

A clearer name for Presentism, then, is tyranny.

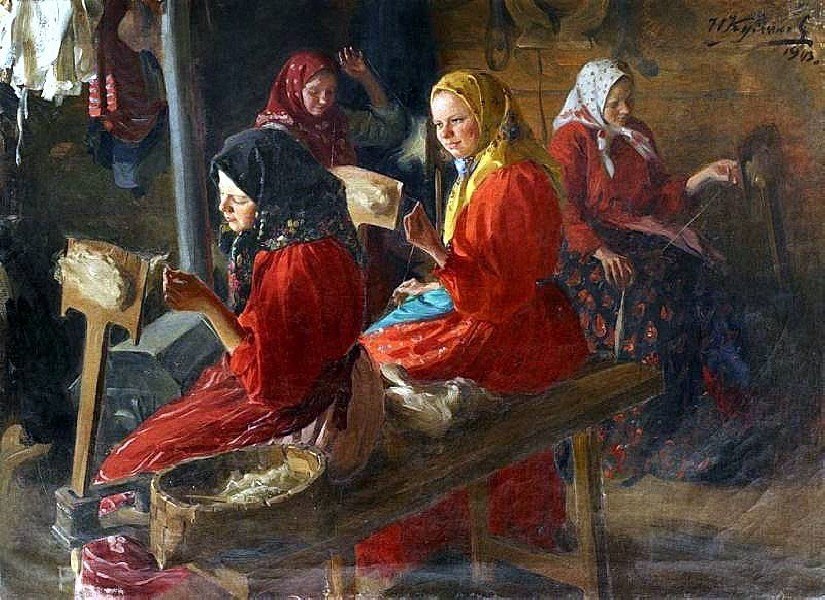

The photo shows, “The Last Sleep of Arthur in Avalon,” by Edward Burne-Jones, painted in 1898.