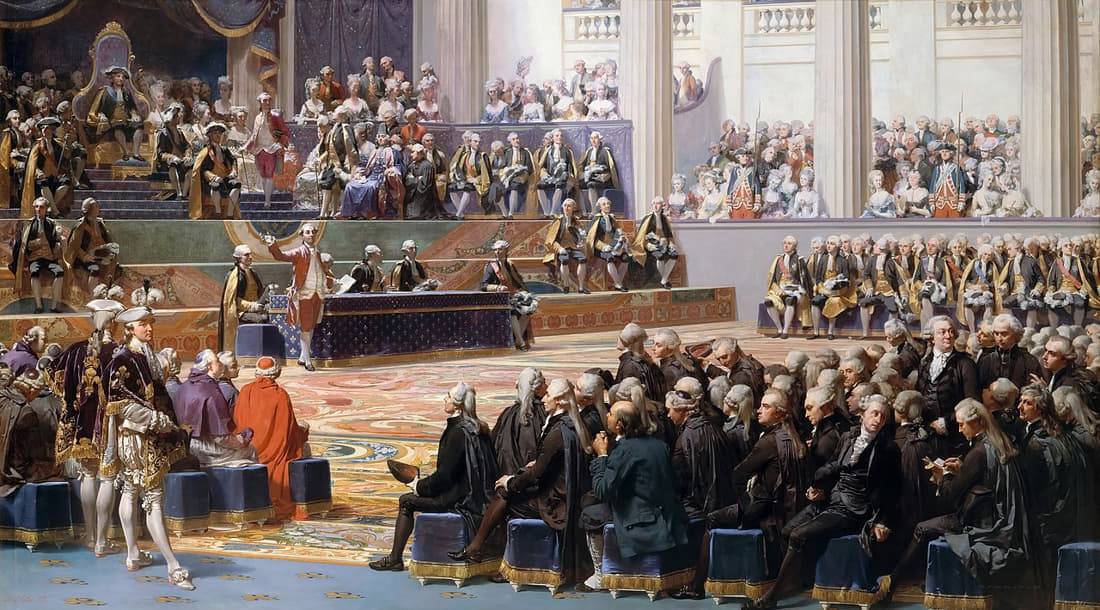

In a recent book, Spanish historian Pedro Carlos González Cuevas (professor at UNED) reminds us about the origins of the concepts of Right and Left. It is a well-known historical episode. On August 28, 1789, the French National Constituent Assembly, debating the role of the king, split into two camps: on the right, those in favor of giving the king decision-making power; on the left, those opposed.

This division symbolized the political bipolarity to come, but it was formed a little earlier, a few months earlier, in the Estates General, still under the Ancien Régime. Society was divided into three orders or states: the clergy, the nobility and the plebeian Third Estate, and some representatives of the first and second states moved closer to the third, taking seats on the left of the hall, while the rest of the clergy and nobility remained on the right.

This is when the “topographical shift” took place. What was vertical in the Ancien Régime, the three orders or states, became horizontal in the modern assembly—right versus left.

There was thus a symbolic parliamentary opposition. But in political terms, the Right-Left divide is even more recent. As Arnaud Imatz puts it: “In public opinion, or rather for citizen-voters, its birth dates back only to the 1870s-1900s, and perhaps even later, to the 1930s. The great cyclical conflict between the eternal Right and the immortal Left is therefore little more than a century old.”

Since then, this polarity has dominated political debate, even if it has not been without its critics. To overcome it is not so much to eliminate differences as to make integration possible: to be both Right and Left.

This vision of overcoming has received, and still receives, generally harsh and dire criticism, because it comes from both sides. It is considered a political abomination. More than a heresy, it is seen as a monstrous degeneration, arousing fierce and incomprehensible hatred on both sides. But there are those who say, perhaps not without reason, that continuing to think and act according to this dichotomy prolongs a situation that pleases the ruling class. How can anything be changed without changing this?

The French story of the transformation of the vertical order of politics into a horizontal one, as if it were the descent or detachment of a Catalan castell (human tower), interests us because it allows us to imagine something similar.

Today, the Left and the Right appear divided. On the Left, we can distinguish between a post-modern, open-minded Left, in tune with the economic powers that be, and a classical Left, with Marxist roots, more conservative in the cultural sphere and more dissenting in the economic sphere. We may call one the cultural Left and the other the economic Left. The former would be more centered, closer to the center of political power.

On the Right, there could be a similar division. There is an economic Right that neglects the cultural, and another that is more concerned with civilizational foundations, with, let us say, less liberal enthusiasm. Here, the economic Right would be more in the center, the cultural Right more “extreme.”

The horizontal plane would thus look like this: Economic Left-Cultural Left-Economic Right-Cultural Right.

This plan is modified by a new axis or tension between globalism and sovereignty. There is a verticalization: the elites who support globalism and its undemocratic institutions on the one hand, and the defenders of national sovereignty on the other. The former receive the urban and high-income vote, and are nurtured by the managerial, cultural, media, financial and expert classes in general; the latter, even on the Right, are favored by low-income populations: working class, agrarian, suburban and populist right-wingers.

This division undermines the Left-Right axis. The economic Right and the cultural Left attract each other, forming around the hinge of the pure center a coalition of liberal and progressive ends and means, in a kind of socio-liberalism.

By contrast, the sovereignist, identitarian Right is relegated to the “extreme,” as is the national, Marxist, anti-Woke Left.

These two political spheres, detached from the globalizing, rising, receding center, fall into another, sovereignist pole. With the development of the elitist socio-liberal “alloy,” and its agreement between the economic Right and the cultural Left, these two blocs are becoming more extreme, more isolated, more separated.

But there are points of convergence: the anti-globalization Left is moving closer to the national; the anti-elitist and populist Right is moving closer to the worker. Both share, with many differences, an opposition to Woke transhumanism.

All that is traditional-biological, national and workerist forms a zone of intersection and rapprochement between these two groups, which have drifted apart in the face of globalism and the “detachment” of the socio-liberal center.

In this way, a verticalization of the axis has taken place, overtaking the Right-Left with positions that have something of one and something of the other, a kind of mixed composition of the two. On the one hand, at the top, a law-and-order globalism with a Wokish economic and cultural liberalism. On the other, at the bottom, culturally conservative sovereignty with nationalist approaches to the economy.

This new axis or division is no longer Left and Right, but top to bottom. If the revolution of 1789 provoked a “topographical shift,” the horizontalization, accumulation of technological revolutions and maturation of the post-World War II framework may well invite us to think of another new topographical rotation. Would techno-globalization-tyranny-Woke not be powerful enough to shake a century-and-a-half-old division?

But, having said that—and it is enough to do the test—the simple suggestion of going beyond the Manichean and bipolar framework achieves the impossible: to bring together the Right and the Left in a chemically pure hatred of this possibility, which in their view would be no more than a kind of abomination or chimera, made up of partial monstrosities of one and the other.

Hughes is Director of the Ideas supplement of La Gaceta de la Iberosfera. He is also one of the foremost columnists in Spain. This article appears courtesy of La Gaceta de la Iberosfera.

Featured: Opening session of the General Assembly, May 5, 1789, by Auguste Couder; painted in 1839.