In the early 1960s, an avalanche of tourists came in the footsteps of those intrepid travelers who toured Spain in search of the preconceived image they had of it. If those distinguished strangers were looking for exoticism, two centuries later, their successors came in search of the so-called “sun and beach tourism” on which was built an industry that has left an indelible mark on the Spanish coastline, once marked by watchtowers that warned of the dreaded arrival of Barbary piracy. The main figure associated with those days is Manuel Fraga Iribarne, Minister of Information and Tourism, to whom we owe the famous phrase, “Spain is different,” a phrase attributed to Napoleon after the defeat at Bailén.

Deindustrialized in exchange for its entry into the European Economic Community, now the European Union, Spain continues to have tourism as one of its main economic strengths. However, despite the fact that the clichéd image of Spain—bulls and flamenco—is largely maintained, the development of the autonomous model has forced the country to seek, if not manufacture, distinct symbols of identity. In the case of Andalusia, whose patriotic paternity has been attributed to a Muladi called Blas Infante, there are many who try to make the region match an idyllic al-Andalus, a model of tolerance and intercultural dialogue. The reverie is not new. In fact, it’s linked with the fantasies of those nineteenth-century travelers and even with those of certain political groups that sought to confront Andalusian democratism with Castilian authoritarianism.

All this is relevant because, for some time now, not only have the theses of Olagüe been rescued by Gonzalez Ferrin, regarding the alleged peaceful arrival of Islam to Spain, but even the concept of “reconquest” has recently been cancelled, as it is considered not only inadequate, but linked to political positions characterized as Spanish-ist or extreme.

In this context, the book by Yeyo Balbás, Espada, hambre y cautiverio. La conquista islámica de Spania (Sword, hunger and captivity. The Islamic conquest of Spain), a work that deals with the expansion of the Islamic empire to its limits, including, but not limited to, Visigothic Spania. An expansion by no means peaceful. Balbas’s book is distinguished not only by a solid handling of the Muslim sources, often ignored by historians attached to the narratives made from the Christian side, but adds a factor that meets the requirements for the cultivation of what Bueno called “phenomenal history”: the relics or vestiges that archeology is revealing. This archaeological aspect endows the book with a sort of verification mechanism that serves to dispel visions, often adjusted to literary canons, of a much more convulsed and fractured past than the usual maps that divide the Iberian Peninsula into two parts, the Christian and the Muslim, tinged with different colors.

Through the pages of Balbas’ book parade characters whose profiles are blurred by legend, but also crude realities such as massacres, crucifixions, slavery or a polygamy under which crimes were committed among factions linked to one or the other heir. The Al-Andalus that emerges in Balbas’ book is not different from the rest of the Dar-al Islam—although, as it is logical, being a Spanish author, he focuses more on Al-Andalus to examine the case of some Christians punished, first, and protected later, because of their Trinitarian God, and whom the Muslims therefore called “polytheists.” This forces Balbas to look at events surrounding the famous Don Julian and Don Rodrigo, that is, the battle of Covadonga, the starting point of a reconquest whose mere mention constitutes, in certain ideological environments, the prelude to anathema.

Iván Vélez is an architect and associate researcher at the Gustavo Bueno Foundation. Author of numerous books and articles. He serevs as the Executive Director of the DENAES Foundation and Coordinator of the p;olitical party VOX in the Parliament of Andalusia. Ths review appears courtesy of Posmodernia.

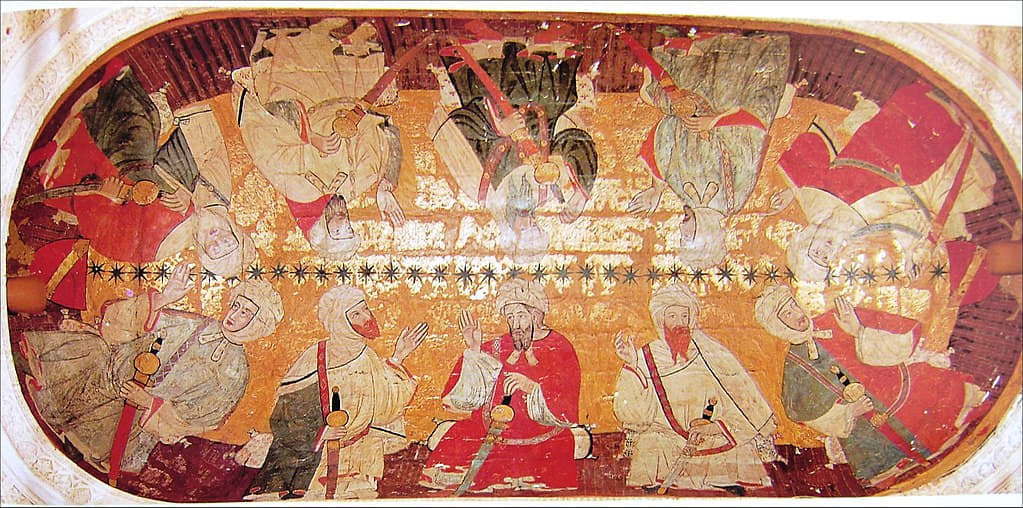

Featured: Late-14th-century Gothic mural painting by a Christian Toledan artist on the ceiling of the Hall of Kings of the Alhambra, possibly depicting the first ten sultans of the Nasrid dynasty.