John Cowper Powys (1872—1963) was an English (and American) essayist, novelist, poet and philosopher. His work is marked by depth of ideas, complexity of character and much humor. He is also, sadly, much-neglected in our time. This excerpt is from Suspended Judgments. Essays on Books and Sensations, which was published in 1916, and which explores the works of men who have had the greatest impact on the Western life of the mind. We hope that this excerpt will serve in some small way to nurture interest in Powys’ work.

The world divides itself into people who can discriminate and people who cannot discriminate. This is the ultimate test of sensitiveness; and sensitiveness alone separates us and unites us.

We all create, or have created for us by the fatality of our temperament, a unique and individual universe. It is only by bringing into light the most secret and subtle elements of this self-contained system of things that we can find out where our lonely orbits touch.

Like all primordial aspects of life the situation is double-edged and contradictory.

The further we emphasise and drag forth, out of their reluctant twilight, the lurking attractions and antipathies of our destiny, the nearer, at once, and the more obscure, we find ourselves growing, to those about us.

And the wisdom of the difficult game we are called upon to play, lies in just this very antinomy,—in just this very contradiction—that to make ourselves better understood we have to emphasise our differences, and to touch the universe of our friend we have to travel away from him, on a curve of free sky.

The cultivation of what in us is lonely and unique creates of necessity a perpetual series of shocks and jars. The unruffled nerves of the lower animals become enviable, and we fall into moods of malicious reaction and vindictive recoil. And yet,—for Nature makes use even of what is named evil to pursue her cherished ends—the very betrayal of our outraged feelings produces no unpleasant effect upon the minds of others. They know us better so, and the sense of power in them is delicately gratified by the spectacle of our weakness; even as ours is by the spectacle of theirs.

The art of discrimination is the art of letting oneself go, more and more wilfully; letting oneself go along the lines of one’s unique predilections; letting oneself go with the resolute push of the inquisitive intellect; the intellect whose rôle it is to register—with just all the preciseness it may—every one of the little discoveries we make on the long road.

The difference between interesting and uninteresting critics of life, is just the difference between those who have refused to let themselves be thus carried away, on the stream of their fatality, and those who have not refused. That is why in all the really arresting writers and artists there is something equivocal and disturbing when we come to know them.

Genius itself, in the last analysis, is not so much the possession of unusual vision—some of the most powerful geniuses have a vision quite mediocre and blunt—as the possession of a certain demonic driving-force, which pushes them on to be themselves, in all the fatal narrowness and obstinacy, it may be, of their personal temperament.

The art of discrimination is precisely what such characters are born with; hence the almost savage manner in which they resent the beckonings of alien appeals; appeals which would draw them out of their pre-ordained track.

One can see in the passionate preference displayed by men of real power for the society of simple and even truculent persons over that of those who are urbanely plastic and versatile, how true this is.

Between their own creative wilfulness and the more static obstinacy of these former, there is an instinctive bond; whereas the tolerant and colourless cleverness of the latter disconcerts and puzzles them.

This is why—led by a profound instinct—the wisest men of genius select for their female companions the most surprising types, and submit to the most wretched tyranny. Their craving for the sure ground of unequivocal naturalness helps them to put up with what else were quite intolerable.

For it is the typical modern person, of normal culture and playful expansiveness, who is the mortal enemy of the art of discrimination.

Such a person’s shallow cleverness and conventional good-temper is more withering to the soul of the artist than the blindest bigotry which has the recklessness of genuine passion behind it.

Not to like or to dislike people and things, but to tolerate and patronise a thousand passionate universes, is to put yourself out of the pale of all discrimination. To discriminate is to refine upon one’s passions by the process of bringing them into intelligent consciousness. The head alone cannot discriminate; no! not with all the technical knowledge in the world; for the head cannot love nor hate, it can only observe and register.

Nor can the nerves alone discriminate; for they can only cry aloud with a blind cry. In the management of this art, what we need is the nerves and the head together, playing up to one another; and, between them, carrying further—always a little further—the silent advance, along the road of experience, of the insatiable soul.

It is indeed only in this way that one comes to recognise what is, surely, of the essence of all criticism; the fact, namely, that the artists we care most for are doing just the thing we are doing ourselves—doing it in their own way and with their own inviolable secret, but limited, just as we are, by the basic limitations of all flesh.

The art of discrimination is, after all, only the art of appreciation, applied negatively as well as positively; applied to the flinging away from us and the reducing to non-existence for us, of all those forms and modes of being, for which, in the original determination of our taste, we were not, so to speak, born.

And this is precisely what, in a yet more rigorous manner, the artists whose original and subtle paths we trace, effected for themselves in their own explorations.

What is remarkable about this cult of criticism is the way in which it lands us back, with quite a new angle of interest, at the very point from which we started; at the point, namely, where Nature in her indiscriminate richness presents herself at our doors.

It is just here that we find how much we have gained, in delicacy of inclusion and rejection, by following these high and lonely tracks. All the materials of art, the littered quarries, so to speak, of its laborious effects have become, in fact, of new and absorbing interest. Forms, colours, words, sounds; nay! the very textures and odours of the visible world, have reduced themselves, even as they lie here, or toss confusedly together on the waves of the life-stream, into something curiously suggestive and engaging.

We bend our attention to one and to another. We let them group themselves casually, as they will, in their random way, writing their own gnomic hieroglyphics, in their own immense and primeval language, as the earth-mothers heave them up from the abyss or draw them down; but we are no more confined to this stunned and bewildered apprehension.

We can isolate, distinguish, contrast.

We can take up and put down each delicate fragment of potential artistry; and linger at leisure in the work-shop of the immortal gods.

Discrimination of the most personal and vehement kind in its relation to human works of art, may grow largely and indolently receptive when dealing with the scattered materials of such works, spread out through the teeming world.

Just here lies the point of separation between the poetic and the artistic temper. The artist or the art-critic, discriminating still, even among these raw materials of human creation, derives an elaborate and subtle delight from the suggestiveness of their colours, their odours, and their fabrics—conscious all the while of wondrous and visionary evocations, wherein they take their place.

The poetical temper, on the other hand, lets itself go with a more passive receptivity; and permits the formless, wordless brooding of the vast earthpower to work its magic upon it, in its own place and season. Not, however, in any destruction of the defining and registering functions of the intellect does this take place.

Even in the vaguest obsessions of the poetical mind the intellect is present, watching, noting, weighing, and, if you will, discriminating.

For, after all, poetry, though completely different in its methods, its aims, and its effects from the other arts, is itself the greatest of all the arts and must be profoundly aware, just as they are aware, of the actual sense-impressions which produce its inspiration.

The difference, perhaps, is that, whereas the materials for the other arts become most suggestive when isolated and disentangled from the mass, the materials of poetry, though bringing with them, in this case or in the other, their particular sense-accompaniment, must be left free to flow organically together, and to produce their effect in that primeval wanton carelessness, wherein the gods themselves may be supposed to walk about the world.

One thing at least is clear. The more we acquire a genuine art of discrimination amid the subtler processes of the mind the less we come to deal in formulated or rationalistic theory.

The chief rôle of the intellect in criticism is to protect us from the intellect; to protect us from those tiresome and unprofitable “principles of art” which in everything that gives us thrilling pleasure are found to be magnificently contradicted!

Criticism, whether of literature or art, is but a dead hand laid upon a living thing, unless it is genuine response, to the object criticised, of something reciprocal in us. Criticism in fact, to be of any value, must be a stretching out of our whole organic nature, a sort of sacramental partaking, with both senses and soul, of the bread and wine of the “new ritual.”

The actual written or spoken word in explanation of what we have come to feel about the thing offered, is after all a mere subordinate issue.

The essential matter is that what we experience in regard to the new touch, the new style, should be a personal and absorbing plunge into an element which we feel at once to have been, as it were, “waiting” to receive us with a predestined harmony.

The point I am seeking to make is that what is called the “critical attitude” towards new experiments in art is the extreme opposite of the mood required in genuine criticism.

That negation of interest in any given new thing which is not only allowable but commendable, if we are to preserve the outlines of our identity from the violence of alien intrusion, becomes a sheer waste of energy when it is transmuted into ponderous principles of rejection.

Give us, ye gods, full liberty to pass on our way indifferent. Give us even the illuminating insight of unbounded hate. But deliver us—that at least we pray—from the hypocrisy of judicial condemnation!

More and more does it become necessary, as the fashion of new things presses insolently upon us, to clear up once for all and in a largely generous manner, the difficult question of the relation of experiment to tradition.

The number of shallow and insensitive spirits who make use of the existence of these new forms, to display—as if it were a proof of aesthetic superiority—their contempt for all that is old, should alone lead us to pause and consider.

Such persons are as a rule quite as dull to real subtleties of thought and feeling as any absolute Philistine; and yet they are the ones who with their fuss about what they call “creative art” do so much to make reasonable and natural the ordinary person’s prejudices against the whole business.

They actually have the audacity to claim as a mark of higher aesthetic taste their inability to appreciate traditional beauty. They make their ignorance their virtue; and because they are dull to the delicate things that have charmed the centuries, they clamorously acclaim the latest sensational novelty, as though it had altered the very nature of our human senses.

One feels instinctive suspicion of this wholesale way of going to work, this root and branch elimination of what has come down to us from the past. It is right and proper—heaven knows—for each individual to have his preferences and his exclusions. He has not, one may be quite sure, found himself if he lacks these. But to have as one’s basic preference a relinquishing in the lump of all that is old, and a swallowing in the lump of all that is new, is carrying things suspiciously far.

One begins to surmise that a person of this brand is not a rebel or a revolutionary, but quite simply a thick-skin; a thick-skin endowed with that insolence of cleverness which is the enemy of genius and all its works.

True discrimination does not ride rough-shod over the past like this. It has felt the past too deeply. It has too much of the past in its own blood. What it does, allowing for a thousand differences of temperament, is to move slowly and warily forward, appropriating the new and assimilating, in an organic manner, the material it offers; but never turning round upon the old with savage and ignorant spleen.

But it is hard, even in these most extreme cases, to draw rigorous conclusions.

Life is full of surprises, of particular and exceptional instances. The abnormal is the normal; and the most thrilling moments some of us know are the moments when we snatch an inspiration from a quarter outside our allotted circle.

There are certain strangely constituted ones in our midst whose natural world, it might seem, existed hundreds or even thousands of years ago. Bewildered and harassed they move through our modern streets; puzzled and sad they gaze out from our modern windows. They seem, in their wistful way, hardly conscious of the movements about them, and all our stirring appeals leave them wearily cold.

It is with the very wantonness of ironic insult that our novelty-mongers come to these, bringing fantastic inventions. What is it to them, children of a nobler past, that this or the other newly botched-up caprice should catch for an hour the plaudits of the mob?

On the other hand, one comes now and again, though rarely enough, upon exceptional natures whose proper and predestined habitation seems to be rather with our children’s children than with us.

The word has gone forth touching what is called super-man; but the natures I speak of are not precisely that.

Rather are they devoid in some strange manner of the gross weapons, the protective skin, adapted to the shocks and jolts of our rough and tumble civilisation. They seem prepared and designed to exist in a finer, a more elaborate, in a sense a more luxurious world, than the one we live in.

Their passions are not our passions; nor is their scorn our scorn. If the magic of the past leaves them indifferent, the glamour of the present finds them antipathetic and resentful. With glacial coldness they survey both past and present, and the frosty fire of their devotion is for what, as yet, is not.

Dull indeed should we be, if in the search of finer and more delicate discriminations in the region of art, we grew blunt and blind to the subtle-edged pathos of all these delicate differences between man and man.

It is by making our excursions in the aesthetic world thus entirely personal and idiosyncratic that we are best spared from the bitter remorse implicit in any blunders in this more complex sphere.

We have learned to avoid the banality of the judicial decisions in the matter of what is called beautiful. We come to learn their even greater uselessness in the matter of what is called the good.

To discriminate, to discriminate endlessly, between types we adore and types we suspect, this is well and wise; but in the long result we are driven, whether it is pleasant to our prejudices or not that it should be so, crushingly to recognise that in the world of human character there are really no types at all; only tragic and lonely figures; figures unable to express what they want of the universe, of us, of themselves; figures that can never, in all the aeons of time, be repeated again; figures in whose obliquities and ambiguities the mysteries of all the laws and all the prophets are transcended!

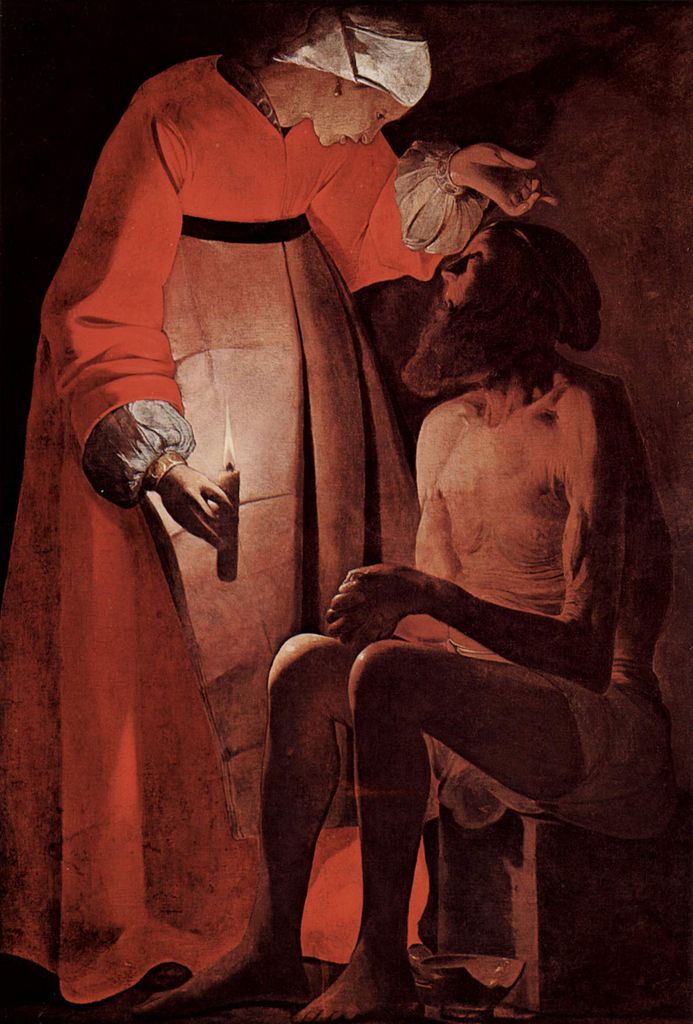

Featured image: “Job mocked by his Wife,” by Georges de La Tour; painted ca. 1650.