At the end of 2013, I wrote to Pope Francis suggesting we have a conversation about the fundamental questions facing Christians in the modern world. It was a naïve proposal, but it never reached him.

The main element and purpose of this article is actually the letter reproduced below, which I wrote to Pope Francis at the end of 2013, with a view to having it delivered by people I thought of as friends of mine who had access to him. It was written in the spirit of a politely-worded offer to assist the pope in clarifying things he had said in a number of recent interviews that appeared either to have been unintentional misspeaks or subject to misappropriation or misquotation. I also wished to dig deeper than any of those interviews had gone, asking the kinds of questions on the minds of serious Catholics rather than liberal-atheistic journalists, especially with regard to the problem of retaining faith in an increasingly pseudo-rational world. At the time I was convinced that he was simply being asked the wrong questions.

The idea was prompted by the first interview he gave to the veteran atheist Italian journalist Eugenio Scalfari, co-founder of the left-wing newspaper La Repubblica, which made the pope sound like an altar boy who had just served his first Mass. But this had been merely the final straw.

Whereas previous popes had tended to issue communications to the world through encyclicals, weekly homilies et cetera, Pope Francis pursued the kind of engagement more commonly identified with politicians — and a rather unconventional one at that. Sometimes, he made his most newsworthy statements apparently off-the-cuff — perhaps on a long plane journey, when he would approach the media section unannounced. Taken together, these interventions were presented as encapsulating his outlook on a range of important doctrinal matters.

From about September of 2013, just six months into his pontificate, the pope issued a series of rapid-fire pronouncements in a string of interviews, each of which seemed to outdo the last in disintegrating Catholic teaching on everything in sight. He apparently picked up the telephone and called Eugenio Scalfari, who had submitted, presumably, a routine request for an interview. “Why so surprised?” the pope asked Scalfari when he was put through. “You wrote me a letter asking to meet me in person. I had the same wish, so I’m calling to fix an appointment. Let me look at my diary: I can’t do Wednesday, nor Monday; would Tuesday suit you?”

In the wide-ranging interview that ensued, the pope spoke inter alia about the nature of good and evil, provoking whispered accusations of relativism from many surprised personages within the Church: “Everyone has his own idea of good and evil and must choose to follow the good and fight evil as he conceives them,” he told Scalfari. “That would be enough to make the world a better place.” Without naming names, the pope accused some of his predecessors of narcissism, and condemned “clericalism” as inimical to Christianity. He also informed Scalfari that he needn’t trouble himself with the “solemn nonsense” of traditionalists who insist that he “enter by the narrow gate.”

In the wake of the interview, the Vatican was forced into an official denial that Pope Francis had claimed to have abolished sin. Scalfari afterwards told the press: “{T]the most surprising thing he told me was: ‘God is not Catholic.'”

There was much commentary among “conservative” Catholic commentators on the question of whether the pope had been misrepresented. Scalfari never uses a recorder or takes notes. His style is to “recall” the conversations he has had with his subjects, and relate in his own words what he remembers. So far, having done multiple discrete interviews with Pope Francis, 99 per cent of what he has published as the Pope’s thoughts has gone uncontested. It has come to seem that, in speaking through Scalfari (an atheist and former fascist), the Pope was pursuing a deliberate strategy — whether for the purposes of sowing confusion or cultivating liberal approval remains a puzzle.

In a number of interviews just before the encounter with Scalfari, the pope had been musing publicly on the question of the Church’s priorities, postulating that it was too preoccupied with abortion and the destruction of the family. Some weeks earlier, an interview with La Civiltà Cattolica, in which he spoke in what appeared to be a similarly “non-judgmental” manner about a number of the headline “moral” issues, was hailed as the manifesto of a pope who had “broken with the past” by announcing new doctrinal initiatives on matters like homosexuality, atheism and women priests:

“We cannot insist only on issues related to abortion, gay marriage and the use of contraceptive methods. This is not possible. I have not spoken much about these things, and I was reprimanded for that. But when we speak about these issues, we have to talk about them in a context. The teaching of the church, for that matter, is clear and I am a son of the church, but it is not necessary to talk about these issues all the time.” Pope Francis’s point here appeared to be that emphasising “moralistic” themes serves to suffocate the deeper message of Christianity.

In Ireland, a spokesman for the (generally liberally-inclined) Association of Catholic Priests said he was “absolutely exhilarated” by the Pope’s words. He complained that his association had been criticised for not being more publicly supportive of the bishops during a recent controversy about abortion in Ireland, adding that the Catholic bishops, who had criticized the Irish Government’s proposal to liberalise anti-abortion legislation, had “overegged their case.” Now, he said, “I see that Pope Francis is saying something similar” [to the ACP].

In fact, even while his remarks in this and the Scalfari interview were being digested, events occurred, and were reported sotto voce, that appeared to convey an entirely different impression concerning the pope’s positions and intentions. During a Papal Audience with MaterCare International as part of the group’s 10th international conference in September 2013, Pope Francis spoke clearly on abortion to a group of obstetricians and genealogists, emphasising that they had a responsibility to make known the “transcendent dimension, the imprint of God’s creative work, in human life from the first instant of conception. And this is a commitment of new evangelisation that often requires going against the tide, paying a personal price. The Lord counts on you, too, to spread the Gospel of life.”

“Every child that isn’t born, but is unjustly condemned to be aborted,” he said, “has the face of Jesus Christ, has the face of the Lord.” He urged them to abide by Church teachings, saying: “Things have a price and can be for sale, but people have a dignity that is priceless and worth far more than things. […] In all its phases and at every age, human life is always sacred and always of quality. And not as a matter of faith, but of reason and science.”

This statement gained close to zero traction in the media, a fact that the pope must surely have noticed. Yet he seemed content to court the attentions of “progressive” journalists without ensuring that they provided a balanced account of his views. The cumulative effect was to create an impression of relaxation in respect of certain core aspects of Church teaching to a media delighted to report that the pope had finally come around to agree with what journalists had been saying all along. The idea that the pope should not talk about such matters “all the time” is hard to argue with, but was hardly the issue. The problem was with giving repeated interviews in which what appeared to be a downplaying of these issues became the headline every time, giving succour to actors and interests with radical intentions concerning Church teaching.

In the first year of his pontificate, Pope Francis announced no new doctrinal initiatives, nor was his emphasis significantly different to that of his predecessor, who had, in the eight years he spent as head of the Catholic Church, accrued no credits at all with the kind of people who lionised Francis as the saviour of Catholicism and the liberator of its dissenting elements. Yet, the “liberal pope” headlines kept on coming. Pope Francis was named Person of the Year by Time magazine, which praised him for his rejection of Church dogma. Not to be outdone, Advocate, an American magazine for homosexuals, also named Francis its 2013 Person of the Year, for the “compassion” he had shown to gay people.

When you examined more closely the total texts of various interviews he had given, it seemed that the pope’s words were being manipulated by selective emphasis. In several passages that gained far less attention, he seemed to tread a more subtle path than the headlines suggested.

For example, when asked in his interview with La Civiltà Cattolica what the Church needed most at this moment, what kind of Church he dreamed of, Pope Francis began by endorsing the humility and graciousness of his predecessor and then continued: “I see clearly that the thing the Church needs most today is the ability to heal wounds and to warm the hearts of the faithful; it needs nearness, proximity. I see the Church as a field hospital after battle. It is useless to ask a seriously injured person if he has high cholesterol and about the level of his blood sugars! You have to heal his wounds. Then we can talk about everything else. Heal the wounds, heal the wounds. . . And you have to start from the ground up.

“The Church sometimes has locked itself up in small things, in small-minded rules. The most important thing is the first proclamation: Jesus Christ has saved you. And the ministers of the Church must be ministers of mercy above all. The confessor, for example, is always in danger of being either too much of a rigorist or too lax. Neither is merciful, because neither of them really takes responsibility for the person. The rigorist washes his hands so that he leaves it to the commandment. The loose minister washes his hands by simply saying, ‘This is not a sin’ or something like that. In pastoral ministry we must accompany people, and we must heal their wounds.”

Superficially apprehended, it seemed that the problem ought to be dissipated by such passages, and yet it was not. As time passed and the pope became more identified with questioning Church doctrine than upholding it — and he himself remained silent when clarifications appeared to be necessary — the sense of a “progressive” papacy became more and more solidified.

Reading over a chapter I was invited to write for a compendium volume of articles on the Francis pontificate, and completed in February 2014, it is clear that I continued to struggle with these questions for some time even after I had completed the letter to Pope Francis. My contribution to the book was substantively a critique of attendant media culture and its responses to the new pope:

The media have chosen to turn the change of popes into a different kind of story — one that will sell newspapers or advertising space with a narrative of revolution and democratisation. . . Francis, like his predecessor, sees the human person in society as floundering in a mess of relativism and unhope, besieged by ideology and disinformation, driven away from the authentic course of the authentic human journey. Francis presents his explanations in the form of anecdote and analogy, placing the listener into a context where the meaning becomes clear on the basis of personal experience and the deep structural appetite for story that resides in every human heart.

In this passage and otherwise, my verdict on Francis himself might seven years later be described as naïve:

Pope Francis, then, is neither a “rigorist” nor a “loose minister.” He seeks to reconcile not merely those inside the Church with those who have fallen away, but also the necessary dogmatism that goes with Truth with the fluidity essential to a living, breathing faith. He is indeed a “breath of fresh air,” but not in the sense that journalists tend to report, or in the way those who oppose virtually everything the Church stands for would lead us to believe.

I had acquired something of a “special interest” in these matters. Over the first Pentecost weekend of his pontificate, on Saturday May 18th 2013, I stood alongside Pope Francis on the steps of St Peter’s and followed him in speaking to a crowd of 250,000 people, the assembled members of the world’s new evangelical movements. I was impressed with him on that occasion, just two months into his pontificate. I was also greatly moved by what seemed to be the latent power of his presence, the breadth of his charismatic skills in communicating. I was stuck in particular by his physicality — the way his whole body seems to be summoned towards the act of communication, and also by the way he spoke to the gathering as though to one person.

I was transported by his description of the necessity for the Church to move out of its stuffy room and take the risk of meeting the rest of humanity. “When the church becomes closed, it becomes sick, sick,” he said. “Think about a room closed up for a year. When someone finally enters there is an odour and nothing feels right. A closed church is the same way; it’s a sick church. If you go out in your car, you risk having an accident, but this is preferable to remaining closed up at home. We need to become courageous Christians, and go out and search for those who are the body of Christ!”

Catholics, he said, must “touch the body of Christ, take on the suffering of the poor. For Christians, poverty is not a sociological or philosophical or cultural category, it is a theological category,” because Christ made himself poor in order to walk the earth, suffer, die and rise to save humanity. “We cannot become stodgy Christians, so polite, who speak of theology calmly over tea. We have to become courageous Christians and seek out those who are the flesh of Christ.”

When I wrote subsequently about the Francis papacy, I leaned over backwards to extend him the fullest credit for the totality of these statements, concluding:

Those who love the Church know now, as they always have, that the “changes” being clamoured for in the world’s media are neither well-advised nor necessary. What is required, as always, is an ear attuned to the heartbeat of the world in time. This must remain the hope of sane people for the pontificate of Pope Francis. The question is: Can the pope stand firm in front of the Truth, against the dictatorship of apparent tolerance?

I was wrong in the substance of these assessments. As the months and years passed, it became clear that either of two things might be true: that the pope’s head had been turned by the favourable attentions of the world’s press (as he increasingly gave them what they wanted); or that he had been Janus-faced from the beginning and had been playing a game of subtle misdirection so as not to scare the traditionalist horses overmuch.

But, as time passed and the pope did almost nothing to disperse the growing disquiet among his own flock, the issue became more and more disconcerting for Catholics who were still disposed to take the Church’s teachings seriously.

One of the most vital questions, then, relates to the role Pope Francis himself may have played in the formation of the narrative surrounding him. At times, it has appeared that he was being, at best, naïve in failing to realize that the media would selectively report and manipulate his words. It also seemed that, in his emphasis on controversial issues, and his selection of sceptical, if not Catholic-averse journalists to communicate with the public, he seemed to be playing to the media’s obsession with issues like atheism, homosexuality, women priests et cetera. It was often unclear whether the confusion the pope left in his wake was a deliberate strategy or the consequence of a chaotic thinking process, but in any event he continued to give succour and comfort to those who hated the Church, while causing dismay to many of those who loved her.

More and more a side of him seemed to emerge that contradicted all attempts to place him in a line following on from Pope Benedict and Pope John Paul II. More and more he seemed to become a political figure, not just issuing gratuitous and ambiguous statements on the headline moral issues — to the extent that he did indeed appear to be “talking about them all the time” — but relocating the Church in a political context in which it had not hitherto appeared comfortable.

In 2015, in his second encyclical, Laudato si’ , he said: “There is urgent need of a true world political authority.” And later:

“When we acknowledge international organizations and we recognize their capacity to give judgment, on a global scale — for example the international tribunal in The Hague, or the United Nations — If we consider ourselves humanity, when they make statements, our duty is to obey. . . We must obey international institutions. The is why the United Nations were created.’

Very frequently, it becomes impossible to avoid that the pope has become, in effect, the ally of the gravediggers of Europe, extolling Islam to the detriment of Christianity and mocking those who regard Christianity as the cornerstone of European civilisation. It is not just that he regularly contradicted Catholic theology and doctrine, but that he appeared to dislike Catholics who took these things seriously. He was sometimes heard sneering at Catholics who are in his view excessively “orthodox.” He spoke of “diversity” and “enrichment” in the manner of a spotty teenager infatuated for the first time with the absurdities of Woke. He talked almost non-stop about “ecumenism” but often seemed actually to despise the faith he was supposed to be leading. Whenever he heard talk of the Christian roots of Europe, he said on more than one occasion, “I sometimes dread the tone, which can seem triumphalist or even vengeful.” He refused to condemn Islamic violence and on occasion equated Islamist jihadists with traditionalist Catholics. He lacerates Church leaders who spoke of an Islamic ‘invasion’ of Europe. As I suggested in an article on the resignation of Cardinal Sarah back in February, what the pope has said about mass migration is a travesty of Catholic teaching.

As time wore on, things grew worse and worse. In January 2017, LifeSiteNews published a comprehensive review of events over the previous year, which gives a robust sense of how things stood at that time.

In October 2019, the pope gave another interview to Scalfari in which he seems to have told him that Jesus was not divine.

Scalfari wrote of that conversation:

“Those who have had the chance, as I have had at different times, to meet him and speak to him with the greatest cultural confidence, know that Pope Francis conceives Christ as Jesus of Nazareth, a man, not God incarnate. Once incarnated, Jesus ceases to be a God and becomes a man until his death on the cross.

“When I happened to discuss these phrases, Pope Francis told me: ‘They are the definite proof that Jesus of Nazareth, once he became a man, even if he was a man of exceptional virtue, was not God at all.'”

This time, the Vatican issued what seemed like a robust denial: “As already stated on other occasions, the words that Dr. Eugenio Scalfari attributes in quotation marks to the Holy Father during conversations with him cannot be considered as a faithful account of what has actually been said, but rather represent a personal and free interpretation of what he has heard, as is quite evident from what has been written today about the divinity of Jesus Christ.”

Yet, the periodic “interviews” with Scalfari continued. The headline statements attributed to the pope — for example, that hell does not exist, that the souls of those who fail to achieve Heaven are simply annihilated rather than eternally punished — remained high up in the mix, while the “clarifications” were forgotten. The confusion of Catholics grew and grew.

Last year, at the height of the Covid-19 global scare, Pope Francis urged Catholics to follow the globalist directives and attacked those who protested against lockdowns. Interviewed for a book by one of his personal evangelists, Austen Ivereigh, he said:

“You’ll never find such people protesting the death of George Floyd, or joining a demonstration because there are shantytowns where children lack water or education, or because there are whole families who have lost their income.”

Did this statement — the holding up of a violent criminal as a worthy martyr and the avoidance of the fact that it was lockdown protestors precisely who drew attention to the escalating losses of incomes, education and hope — represent the real mind of Francis? It appeared so. Last year too, he endorsed the pro-abortion Joe Biden for the US presidency, over the incumbent Donald Trump, the most vocal anti-abortion president in recent history.

Increasingly it has seemed as if, in his own mind, the pope sees himself as something like a monarch or statesman, who contributes to discussion of the mix of forces in conflict in culture, but is in no way serious about the claims of Christianity from the beginning. How could he be serious about these, when he celebrates their antitheses and drops hints that the core teachings of the Church may be simply myths or fables?

My letter to Pope Francis requesting an interview, written as 2013 came to a close, was an act of naiveté on my part, at the time mistaking him for the naïve one. I thought to get to the pope at a time when it seemed he was being grossly manipulated and misrepresented, and, rather than dancing to the tune of the Church’s sworn enemies, have him speak about what was important for the role of the Church in the world.

My objective was not necessarily to have him contradict anything he had said, but to speak about more fundamental things that would not seem important to someone who was not a Christian or Catholic. But I also hoped to give him a chance to contextualise some of his more notorious statements, so that what I presumed at the time to be misquotations might be clarified for the benefit of increasingly confused Catholics.

In this endeavour, I believed I had the support of some senior people in a Catholic lay community, the Italian movement Comunione e Liberazione (CL/Communion and Liberation) which had strong links to the new pope. Although Wikipedia has it otherwise, I was not myself a member of CL, having simply accepted a series of invitations to speak to its membership all around the world over the course of a decade or so.

Initially, I raised my concerns with a senior member of the movement, who agreed with me about what was happening and actually made the suggestion of requesting an interview. At his instigation I wrote the letter, which he greeted with enthusiasm. I made it clear that I was not necessarily proposing myself as the interviewer — I spoke minimal Italian or Spanish, the pope spoke no English — but simply wanted to influence some kind of change in the way the pope was coming across, or at least provoke a more coherent sense of the connections between the pope’s refinements of the Church’s message and fundamentals of Christianity going much deeper than the most pronounced traditionalism. This “self-effacing” notion was repudiated: I should do the interview if it were granted.

The letter was presented to the leaders of CL in Italy, who immediately dismissed the idea — the first clear intimation I had that something more than papal naiveté was afoot. I remember subsequently speaking to the president of the movement, Father Julián Carrón, who told me that there was “no necessity” to clarify what the pope was saying: “Everyone is able to find out what the pope thinks. There is no confusion!” This response confused me a great deal. In due course I figured out that, since Fr Carrón had direct access to both Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI and Pope Francis, the chances were that the powers-that-be already knew that a change of wind had occurred and had decided they were not going to do anything that might risk the disfavour of the new boss. In any event, the letter was never delivered.

From that moment, my relationship with the movement began to undergo a radical cooling — from the CL side. This situation was somewhat confused by the fact that Ireland soon afterwards entered a lengthy period of public tumult concerning several of the kinds of issues the pope had seemed to be telling us were no longer important —marriage, parenthood, family, human life, and so forth — and I was to become visible in fighting these battles on what the pope would undoubtedly consider a “traditionalist” or “moralistic” platform.

I was also, very shortly afterwards, targeted by the increasingly virulent LGBT movement, which clearly regarded my presence at the centre of Irish journalism as a possible obstacle to its planned demolition of the Irish Constitution. In fact, although my views on these matters coincided with Catholic teaching, and I was myself a professed Catholic, these two circumstances were not interdependent. By then, my positions were well rooted in my own life experience, and would have survived even a total disenchantment with the Catholic Church.

I don’t know if I would answer to the name of “traditionalist” in any category. I believe in the power and value of tradition, but tend to think the “-ism” part leads to sclerosis, for example to a kind of theme-park Christianity that becomes more a hobby or identity-prop than anything else. As a boy in the last 1960s, I served the Latin Mass, and sang the High Mass in Latin at funerals. I believe the loss of Latin was a critical blow to the connection between the Church and the people. But my principal concern, as my letter to Francis abundantly conveys, was with the erosion of the transcendent imagination of the West, a factor that nobody, now the voice of Ratzinger/Benedict had fallen silent, appeared to be addressing.

The letter episode was more or less the beginning of the end of my relationship with CL. Invitations to speak at its events dried up overnight, apart from a handful of distant outposts where the memo did not arrive, and all of these have since succumbed. This caused me no little distress. I had been deeply attracted to the reasonable, Newmanesque elements of the movement’s founder, Don Giussani’s reflections on the meaning of Christ in the modern world, and also attracted to the spirit of cultural (not religious) modernity in his movement. When Francis arrived, this seemed to change overnight into full-on “progressivism.”

And since this letter of mine to the pope, I would in all modesty and gratitude say, might almost as plausibly have been written by Don Giussani, this left me in no doubt as to the total meaning and direction of things:

My Letter To Pope Francis

Holy Father,

I met you briefly last May, over the Pentecost weekend, when I made a short speech to the assembled members of the new evangelical movements, in your presence, and again next morning when we exchanged a greeting after breakfast.

I am an Irish journalist. For more than 20 yeas I have been a columnist with The Irish Times, which is Ireland’s equivalent of La Repubblica — a ‘liberal’ newspaper addressing the more educated elements of the population. During the time I have been writing for the newspaper, I have undergone many experiences, which I have tried to write about in my columns in as far as they relate to issues of a public nature or matters that may touch the lives of others. One of my themes has been my journey back to faith, which I have chronicled also in a book, Lapsed Agnostic, which I gave you on the morning of our second encounter last May. I perfectly understand that you may not have had time to read it, but the title conveys the general sense of its content. It is the reflection of someone who, having unthinkingly followed the course of the contemporary cultural slide towards unbelief, was arrested by circumstances and obliged to consider things more deeply.

We live in times that may be without parallel in human history. I have a daughter, aged 18, who is of a generation that has started out into a world radically different than the one I grew into a generation ago. Something fundamental has changed in our cultures, which appears to be related to leaps in communication — what technology appears capable of delivering for us now compared to even two decades ago. There is a sense that everything has changed, that some kind of cleaver has come down hard upon our culture, severing the lines of connection to the past — even to parts of the present. More and more people appear to be imprisoned within technological compounds in which their immediate desires and requirements are gratified, and yet their most basic questions are not merely ignored but actually denied, even suppressed. There is an escalating sense that people are slipping into an adjacent but unreal world, in which they can act out a fantasy of living while actually avoiding the reality.

These words of Gabriel Marcel seem apt: ‘At the very depth of ourselves, we don’t know what is happening. We don’t even know if anything is happening. We throw the net of our interpretations into depths that are impenetrable in every respect . . . We draw out only phantasms, or at least we cannot be sure that they may be anything else.’

In these conditions, what reality is has become distorted, so that both the plausibility of and the necessity for a belief in the transcendent have come into question. Faith seems superfluous to a life that might be made as comfortable and satisfying as humanly conceivable by the simple acceptance of a certain limited version of the human. Who needs hope? What is there to hope for? Why not abandon hope and live the moment instead?

In these conditions — which may have been implicit from the start but are certainly exacerbated in our times — it seems that the human person can connect truly with reality only in extreme youth, when what the world calls ‘innocence’ prevents him being caught up in the collective delusion, and in extreme proximity to death, when he realizes that nothing of what he has lived or learned in the cocoon of modernity serves his needs in those guttering moments. Without necessarily anyone planning it, we appear somehow to have generated a form of culture in which ‘not hoping’ appears to be the natural order, the most ‘reasonable’ response and the easiest way of ‘getting though’ life. Religion seems to offer only a desiccated certitude, a determined attempt to elide a total emptiness.

For several years now I have tried to elucidate the meaning of my own journey with a view to combatting these tendencies of our culture, but always struggling against the limits of language and the reductions which modern reality and its self-definitions and self-descriptions has succeeded in imposing on the great questions of existence. I have long felt that, simply by virtue of electing to speak of such things, one becomes trapped on one side of a veil of cultural prejudice, thus rendering it almost impossible to speak in ways that might alert and encourage the one who remains trapped behind that veil — still struggling to reconcile an ‘educated’ awareness of the modern world with an experience of being human that seems all the time to be excluded from everything that hurtles onwards as part of this caravan of modernity. I have tried to explain many times what I have experienced, what I have felt, what I have learned; but more and more it has seemed to me that I communicate only with those who believe they have already understood what I wish to say (and I’m rarely convinced that we speak the same language), whereas those whose realities most dramatically exhibit the conditions from which I have myself lately journeyed are too solidly settled in their assumptions, or too resistant to the kind of language I must necessarily use, to hear anything I might say.

If this syndrome could be said to afflict only myself and my attempts to explain my journey, it might not amount to a great problem. But I believe this condition is now widespread in what we think and speak of as ‘the modern world’. More and more, it seems, words and self-descriptions tend to trap us in definitions that really amount to no more than reactions, or counter-reactions, to phenomena that provoke, disturb or antagonise us. We become, more and more, political beings, whose self-descriptions and outward manifestations of our self-understandings tend to be off-the-peg identikits, which we inhabit by a process of willed certainty. We ‘invent’ ourselves by numbers so as to avoid the given nature of ourselves.

Our mysterious, given humanity, however, is a different matter. It remains bound inside the identikit personality, as though by an ideological girdle. Each of us is accompanied, whether we wish to focus on it or not, by the ineluctable idea of a total trajectory, a careering through the dizzying stratosphere of existence. That we can find no words for this does not change it. But what can indeed change it is the feeling — picked up from the common conversation — that, because we have no words for it, and because the words we do have seem to exclude it, this sense of a total trajectory in infinity must be an illusion. Only under the utmost pressure, or under conditions whereby reality encroaches with a radical determination, is the human person placed again in front of the questions that define him or her. We speak of our beliefs — or unbeliefs — but the language we use is necessarily of a collective conversation out of sync with both reality and with ourselves.

I have recently been re-reading Vaclav Havel’s speech to the 1989 Frankfurt Book Fair — delivered through the voice of the actor Maximilian Schell — when he won the German Booksellers’ Peace Prize that year (just a month before the Berlin Wall came down). Words, he said, ‘are a mysterious, ambiguous, ambivalent, and perfidious phenomenon.’ Were the words of Marx and Lenin, he asked, ultimately liberating or enslaving? Both at once, he hazarded. Were the words of Christ the beginnings of a new era of salvation or the seeds of the inquisitions? Both, too. The word ‘socialism’, he noted, had begun as ‘a mesmerising synonym for a just world’ into ‘an ordinary truncheon used by certain cynical, moneyed bureaucrats to bludgeon their liberal-minded fellow citizens from morning until night.

‘At one moment in history, courageous, liberal-minded people can be thrown into prison because a particular word means something to them, and at another moment, the same kind of people can be thrown into prison because that same word has ceased to mean anything to them, because it has changed from the symbol of a better world into the mumbo jumbo of a doltish dictator.’ No word, he said, comprises only the meaning assigned to it by an etymological dictionary. ‘Every word also reflects the person who utters it, the situation in which it is uttered, and the reason for its utterance. The same word can, at one moment, radiate great hope; at another, it can emit lethal rays. The same word can be true at one moment and false the next, at one moment illuminating, at another, deceptive. On one occasion it can open up glorious horizons, on another, it can lay down the tracks to an entire archipelago of concentration camps. The same word can at one time be the cornerstone of peace, while at another, machine-gun fire resounds in its every syllable . . .’

‘What a weird fate’, he declared, ‘can befall certain words!’

This tendency for words to change their meanings has always existed, but has recently been subjected to a kind of exponential acceleration due to the explosion of technological communication via the Internet etc. The periods of growth, vibrancy and disintegration experienced by particular kinds of words become more and more ‘speeded up’, due to the rapid-fire cultural processes and ubiquitous technologies available to modern culture. And these processes and technologies also have the power to provoke passivity — just as much as reactions — towards such developments in the hearts of observing humanity, and this has the potential to leave everyone behind while seeming to embrace whole races and peoples, for culture to exclude the heart of each man while seeming to address and speak for everyone.

I believe this question of the limits of language is one that needs to accompany us all the time when we seek to speak of what we believe and know. Don Giussani — for whom I know you have a great affection — spoke of finding ‘the least inadequate words’ (to describe the great mysteries of existence). Yet, our cultures and their collective conversations increasingly treat words as though in a courtroom, pinning meanings down to the point where nothing but the words is necessary. Modern societies tend more and more to regard words as if they were fixed and utterly reliable, or capable of becoming so. Positivism, the programme by which our public thought is processed, seeks to deny or ignore the organic nature of language. Ideology, in which not merely thought but also sentiment is disseminated, requires words to have fixed, legalistic meanings, aloof from life. This means that, by definition, we are all — each in his or her own cocoon — adrift from the understandings supposedly held in common, because each of us is mystery, especially to himself. (I would define mystery not as simply the unknown or even the potentially unknowable, but that which is ineluctable but beyond description — what we know but cannot show to someone who refuses to see.)

We use the least inadequate words. Words are really like loose stones that provide for makeshift paths across treacherous stretches of molten lava: If you move quickly you may be able to use them to reach your meaning. If you get stuck on a word, both you and your intentions are doomed. Really, we cannot ‘tell’ one another anything. We can but point, nudge, gesture and look for signs of recognition. If you try to hold one another to our words, they will disintegrate in front of our eyes. But if we take as read their ultimate unreliability to be anything other than stepping stones, we are at the point of take-off.

I am interested in talking with you about how we might go about overcoming these and other difficulties of the modern world. I have observed with great interest, and no little excitement, the manner in which you have entered into your pontificate. I have been struck in particular by your openness, your willingness to talk frankly and plainly about the crises facing the world, and the Church, and the connections between them. Much that you have said has moved me and encouraged me. But there has been, I feel, a certain lacuna, and this relates to what I have tried to outline in the few sentences above. I would describe this really as relating to the most fundamental question(s) of all.

The interviews you have given so far have been extremely helpful to many people — some Christian, some Catholic, but also some who have drifted from faith, or even reacted against it. But so far, I feel, the emphasis placed on the significance of your leadership has tended to dwell on matters doctrinal, political or even ideological. This has not been of your doing, I feel, but rather has to do with the selectivity and emphases with which your words have been presented by those who happened to be your mediators. Still, in spite of these limitations, you have made a striking entrance and caused many people to look up and consider again what might be missing from their lives.

And yet there are these blocks, which I referred to already, which I believe prevent your words penetrating as they need to, into the depths of present-day culture. I was greatly stuck on May 18th last, by your call to the Church to go ‘to the outskirts of existence’ to spread the Gospel of Jesus Christ. The phrase seemed to me to gesture far beyond geography, or sociology, or ideology, or even the idea of allegiance to a faith, or even to faith itself. It struck me really as a call to me as a human being, a man, in my most fundamental essence – beneath everything I have learned, heard or come to believe — to call me to the question of who I am and what my destiny is.

This is why I would like to talk with you with a view to publishing our exchange. What I believe is required is a far more basic conversation, in which the most fundamental questions might be addressed with a clarity that, if I am right in what I sense about this moment, would cause the world to be struck in a new way.

I have in mind questions like this:

‘What is there to know?’

‘What prevents us from knowing?’

‘How do we reintegrate the mysteriousness of our own existence alongside our growing sense of knowledge about so many things that seem to propose a more concrete existence in the present moment, albeit an existence that leads nowhere?’

‘Even if I have arrived at the possibility that there is a “thou” who lives within me, how do I make what appears to be the considerable leap to calling this “thou” by the name of “Christ”?’

‘Is it possible for a modern, educated person to believe in the divinity of Jesus Christ?’ (The Dostoyevsky question).

‘When I speak of “the presence” of Christ, what do I hope to make visible that is not some sentimental construct, propelled by an insistent moralism? Can I speak truly, really, about such things and not think myself mad, let alone avoid being thought mad by others?’

‘What does it mean to pray? To whom do I speak — someone in the sky, someone within myself? How, in a world which insists on visualisation, do I make this reasonable to myself?’

These questions and many others occur to me. I am not a theologian. Neither am I someone with an agenda within the Church. I do not belong to any faction. I am neither a liberal nor a conservative. I am a man who wants to know, to find words to speak what I have discovered and to initiative conversations to help myself and others. I come to you only from the depths of my own humanity, seeking to formulate sentences which might allow me and others to see more clearly.

My questions are not about ‘the future of the Church’ but about the future of this man, that woman, the child not yet born. My obsession is not with doctrine, but with hope, not with politics but with life and what it may be. To conduct such a conversation would be very difficult, because it would be essential that the words used be of the utmost lightness, refusing the legalistic definitions usually imposed by the codes of journalism and the channels we use to say things.

This is where I believe the richness of Christianity remains vibrantly capable of speaking to the world. The word ‘Christ’ I would call a wordless word. It is a word that dissolves into the mystery it evokes. It takes us to that vanishing point and somehow suggests the possibility of accompaniment beyond. It names a man, but also defines the otherness which we know we belong to but cannot describe, and therefore risk dismissing. It names the Host who inhabits us, but also the Other towards Whom we walk in confidence and anticipation.

The word ‘Christ’ dissolves on the tongue. We can comprehend it in a literal, historical way, but we can also use it as a kind of rocket launcher, to take us elsewhere. It is a word capable of contradicting itself, as only a mystery can. But something strange has happened even to this word: Christ is capable still of animating our imaginations, of proposing a correspondence with our desires that has no equal in the world, and yet the very power of this hope is what causes it to be undermined because it so often seems that our skepticism — arising from our fear of hoping — is stronger, capable of destroying that which we sense can make us whole.

For me, then, the ‘outskirts of existence’ are to be found in each of us, at the extremities of what we think we know, and are able to speak — at that point where we are still able to state, in the most adequate words we can find, what we can say with clarity about what is and what might be. The trouble is that so few today feel equipped or emboldened enough to embark upon this journey, partly because we are incessantly told there is nothing to discover except darkness, and partly because our experience is that the words drag us into themselves, causing us to become lost in the literal and the concrete

There is, I believe, a way of going at these matters with words: to approach the use of words in a manner that will allow them to lift us off into the otherness beyond the literal and concrete, so that we leave all words behind. Any conversation about these matters must obviously bear this paradox in mind. In a sense, we speak words to take us to the vanishing point — to say what we are, what we believe, what we hope for — but then we continue, without words, into the wordless ether, free from everything, including our conventional selves.

So, I would like to go with you, to the very outskirts of human existence, to see what we can see, and see whether we can capture this in words. It is a difficult challenge, as I have outlined. But the very fact that we are aware of the difficulties may make them a little easier to overcome.

Yours in infinite curiosity,

John Waters

John Waters is an Irish writer and former journalist who was at the centre of his country’s cultural and political debate in the past 40 years of unprecedented onslaught on its culture and traditions. He is a playwright, songwriter and the author of 10 books, including two accounts of his efforts at spiritual survival in the encroaching secular tide, Lapsed Agnostic (2008) and Beyond Consolation (2010). His most recent book is Give Us Back the Bad Roads, an account of the unhinging of Ireland under the forces of cultural neo-colonialism (2018). He is a husband and father and lives between Dublin and the Wild West, where he was born.

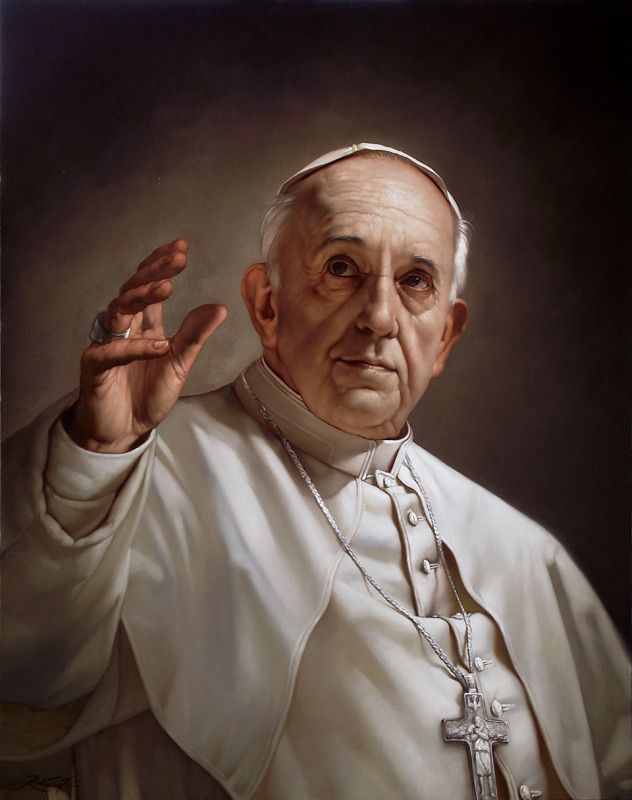

The featured image shows, a portrait of Pope Francis.