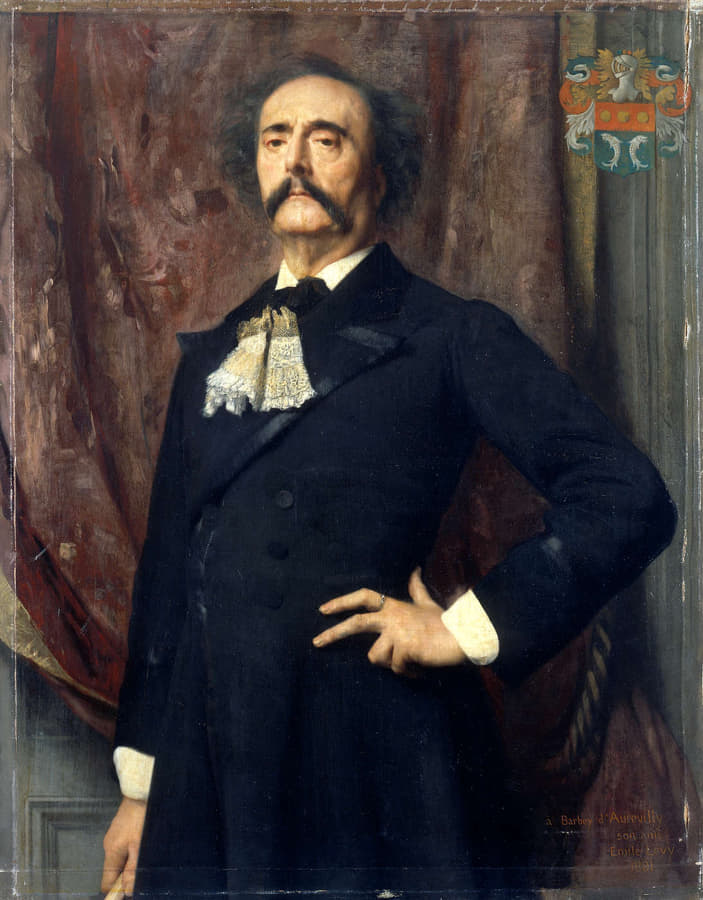

The “Preface” to The Last Mistress (Une vieille maîtresse), by Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, is a well-known defense of the Catholic novel. The work of Barbey (1808–1889) is exceptional for its depth and its beauty. He belonged to a Norman aristocratic family, was a firm Catholic, a monarchist, and also a man who stressed the importance of refinement (dandyism). He was a prolific writer, who consistently published novels, poems and essays. His influence on writers and thinkers has been profound.

“Preface” to New Edition of The Last Mistress

This novel was first published in 1851.

At that time, the author had not embarked on the path of convictions and ideas to which he gave his life. He had never been an enemy of the Church. On the contrary, he had always admired it as the greatest and most beautiful thing on earth, but only in human terms. Although a Christian by baptism and respect, he was not one by faith and practice, as he has now become, thanks to God.

And since he did not simply pull away his mind from the systems to which he had, in passing, clung, but that, to the extent of his action and strength, he fought philosophy and will fight it as long as he breathes, Freethinkers (Libre Pensée), with their customary loyalty and broad-mindedness, did not fail to oppose his recent Catholicism with an old-fashioned novel, which dares to be titled, The Last Mistress, and whose aim was to show not only the intoxications of passion, but also its enslavements.

Well, it is this opposition between such a book and his faith that the author of The Last Mistress intends to reject today. He in no way admits, whatever the Freethinkers may like to say, that his book, for which he accepts responsibility since he is republishing it, is really an inconsistency with the doctrines that are, in his eyes, the very truth. With the exception of a libertine detail of which he admits guilt, a detail of three lines, and which he has removed from the edition he now offers to the public, The Last Mistress, when he wrote it, deserves to be classed with all those compositions of literature and art whose object is to represent the passion without which there would be no art, no literature, no moral life; for the excess of passion is the abuse of our freedom.

The author of The Last Mistress was then, as he is now, no more than a novelist who painted passion as it is and as he saw it, but who, in painting it, condemned it on every page of his book. He preached neither with it nor for it. Like the novelists of the Libre Pensée, he did not make passion and its pleasures the right of man and woman, and the religion of the future. True, he expressed it as energetically as he could, but is this what he is being reproached for? Is it the ardor of his color as a painter that he must catholically accuse himself of? In other words, is not the question raised against him with regard to The Last Mistress much higher and more general than the interest of a book that was not being talked about all the time, for lack of a reason to throw it in its author’s face? And is not this question, in fact, that of the novel itself, which the enemies of Catholicism forbid us Catholics to touch?

Yes, that’s the question! Put like that, it is impertinent and comical. Take a look! In the morality of the Libres Penseurs (Freethinkers), Catholics are not allowed to touch romance and passion, on the pretext that their hands must be too pure, as if all wounds that spurt blood or poison did not belong to pure hands! They cannot touch drama either, because that is passion again. They must not touch art, literature or anything else, but kneel in a corner, pray and leave the world and Free Thought alone. I certainly believe that Freethinkers would want that! If it is buffoonish on the one hand, on the other, such an idea has its depth. I do believe they would like to get rid of us by such ostracism, to be able to say, having blocked all avenues, all specialties of thought: “Those wretched Catholics! Are they distant from all the ways of the human spirit!” But frankly, we need another reason than that, to accept, with a humble and docile heart, the lesson that the enemies of Catholicism are kind enough to teach us about the Catholic consequence of our actions and the fulfillment of our duties.

And to bring things out in the open, by the way, how do they come to know about Catholicism? They do not know the first thing about it. They despise it too much to have ever studied it. Is it their hatred that has surmised the spirit beneath the letter? What is morally and intellectually magnificent about Catholicism is that it is broad, comprehensive, immense; that it embraces the whole of human nature and its various spheres of activity; and that, over and above what it embraces, it still deploys the great maxim: “Woe to him who is scandalized!” There is nothing prudish, pompous, pedantic or restless about Catholicism. It leaves that to false virtues, to shorn Puritanisms. Catholicism loves the arts and accepts, without trembling, their audacity. It accepts their passions and their paintings, because it knows that we can learn from them, even when the artist himself does not.

There are terrible indecencies for impure minds in Michelangelo’s painting (The Last Judgment), and in more than one cathedral there are things that would have made a Protestant cover his eyes with Tartuffe’s handkerchief. Does Catholicism condemn them, reject them and erase them? Did not the greatest Popes and the holiest saints protect the Artists who did these things, which the austere Protestants would have abhorred as sacrilegious? When did Catholicism forbid the recounting of an act of passion, no matter how awful or criminal it may have been, the drawing of pathetic effects from it, the illumination of a chasm in the human heart, even though there might be blood and mire at the bottom of it; in short, the writing of novels, that is to say, of history that is possible when it is not real, that is to say, in other words, of human history? Nowhere! On the contrary, it has allowed everything, but with the absolute reservation that the novel would never be a propaganda of vices or a preaching of error; that it can never allow itself to say that good is evil and evil is good, and that it can never be sophistry for the benefit of abject or perverse doctrines, like the novels of Madame Sand and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. With this proviso, Catholicism has even allowed vice and error to be portrayed in their deeds, and to be portrayed in their likeness. It does not clip the wings of genius, when there is genius.

Catholicism would not have prevented Shakespeare, if Shakespeare were Catholic, from writing that sublime scene which opens Richard III, in which the desolate woman who follows the coffin of her husband, poisoned by her brother, after spewing appalling imprecations against the murderer, ends up giving him her wedding ring and surrendering herself to his false and incestuous love. It is abominable, it is dreadful, the simpletons even say improbable, because this hideous change of a woman’s heart takes place in the short duration of a scene, which is, in my opinion, one more truth; yes, it is abominable and dreadful, but it is beautiful in human truth; profoundly, cruelly, frighteningly beautiful; and truth and beauty, of whatever kind, are not subtracted or abolished by Catholicism, which is absolute truth. And, mind you! Shakespeare does not dogmatize. He exposes. He does not say or make the spectator say: “Richard III is right. The woman he seduces over the warm body of her murdered husband is right to let herself be seduced by the murderous brother-in-law who is now king.” No! he says: “Such it is;” and with the superb impassivity of the artist, who is sometimes impassive, he makes it seen, and in a way so powerful that the heart writhes in the chest, and the brain is struck by it as by a shock of lightning electricity.

Well, now, descend from Shakespeare to all artists, and you have the process of art that Catholicism absolves, and that consists in diminishing nothing of the sin or crime that was intended to be expressed.

But there is more, and Catholicism goes even further. Sometimes vice is amiable. Sometimes passion has eloquence, when it tells or speaks, that is almost a fascination. Will the Catholic artist shrink from the seductions of vice? Will he stifle the eloquence of passion? Should he refrain from painting either, because they are both powerful? Will not God, who has allowed them to man’s freedom, allow the artist to put them in his work in his turn? No, God, the Creator of all realities, forbids none of them to the artist, provided, I repeat, that the artist does not make of them an instrument of perdition. Catholicism does not shun art for fear of scandal. In fact, sometimes scandal is a good thing.

There is something (if you will pardon the expression) more Catholic than you would think in the inspiration of all those painters who have taken pleasure in depicting splendid beauty, like gold, purple and snow, of this butcheress, this Herodias, the assassin of Saint John. They did not deprive her of any of her charms. They have made her divine in beauty, looking at the severed head offered to her, and she is all the more infernal for being so divine! This is how art should work. To paint what is, to grasp human reality, whether crime or virtue, and bring it to life through the almighty power of inspiration and form, to show reality, to enliven even the ideal—that is the artist’s mission. Artists are catholically below Ascetics, but they are not Ascetics; they are artists. Catholicism hierarchizes merit, but does not mutilate man. Each of us has his own vocation within his own faculties. Nor is the artist a police prefect of ideas. When he has created a reality, by painting it, he has accomplished his work. Ask nothing more of him!

But I hear the objection, and I know it: But the morality of his work! But the influence of his work on the already shaken public morality! etc., etc., etc.

My safe answer to all this is that the artist’s morality lies in the strength and truth of his painting. By painting reality, by infiltrating it, by breathing life into it, he has been moral enough: he has been true. Truth can never be sin or crime. If a truth is abused, too bad for those who abuse it! If a living, true work of art leads to evil conclusions, too bad for the guilty reasoners! The artist has nothing to do with the conclusion. “He lent to it,” you may say. Did God lend to man’s crimes and sins when He created the free soul of man? Did He lend to the evil that men can do, by giving them everything they abuse, by putting His magnificent, calm and good creation in their hands, under their feet, in their arms? Come now, I have known imaginations so unbridled and carnal that they felt the fiery lash of desire as they gazed at the lowered eyelashes of Raphael’s Virgins. Should Raphaël have stopped to avoid this danger, and thrown into the fire his Vierge d’Albe, his Vierge à la Chaise, and all his masterpieces of purity, apotheoses of human virginity repeated twenty times over? For some people, is not everything a stumbling block, an opportunity to fall? Should Art expire defeated by considerations that support all failures? Should it be replaced by a preventive system of high prudence that allows nothing of anything that could be dangerous, i.e., ultimately, nothing of nothing?

The artist creates by reproducing the things God has made, which man distorts and upsets. When he has reproduced them exactly, luminously, he has, it is certain, as an artist, all the morality he should have. If one has a fair and penetrating mind, one can always draw from one’s work, disinterested in anything that is not the truth, the teaching, sometimes contained, that it envelops. I am well aware that we sometimes have to dig deeper, but artists write for their peers, or at least for those who understand them. And besides, is depth a crime? Surely Catholic wisdom is more vast, more rounded, more frank and more robust than the Moralists of the Libre Pensée imagine. Let them ask the Jesuits, those astonishing politicians of the human heart, who understood morality so greatly, who saw it from so high up, when on the contrary the Jansenists shrank it and saw it from so low down, making it so narrow, so silly and so hard! Let them question one of those Casuists with a spirit of discernment and relief, such as the Church has produced so many of, especially in Italy, and they will learn, since they are unaware of it, that no prescription rips from our hands the passion whose history the novel writes, and that the narrow, chagrined and scrupulous Catholicism they invent against us is not the one that has always been the Civilization of the world, both in the order of thought and in the order of morality!

And this is not a theory invented at pleasure for the needs of a cause, it is the very spirit of Catholicism. The author of The Last Mistress asks to be judged in this light. Catholicism is the science of Good and Evil. It probes the kidneys and hearts, two cesspools filled, like all cesspools, with an incendiary phosphorus; it looks into the soul—this is what the author of The Last Mistress has done. He has described passion and its faults, but has he apotheosized it? He has described its power, its interlocking, the kind of bar it puts in our free will, as in a distorted coat of arms. He has not narrowed either passion or Catholicism, while painting them. Either The Last Mistress must be absolved of what it is, whatever it is, or we must give up this thing called the novel. Either we must give up painting the human heart, or we must paint it as it is.

If only the gentlemen of the Libre Pensée, so devoted to social interests as we know, found The Last Mistress subversive. Her! But the author, in telling this sad story, could have been impassive, and he was not! He condemned Marigny, the guilty husband! He made him feel remorse and even shame! He made him confess to his grandmother and condemn himself. But his wife, to whom Marigny eventually begs forgiveness, does not forgive him! No novelist has been more the Torquemada of his heroes than the author of The Last Mistress. Yes, passion is revolutionary; but it is because it is revolutionary that it must be shown in all its strange and abominable glory. From the point of view of the Order, the history of revolutions is a good story to write.

That is what we have to say to the gentlemen of the Libre Pensée! Let us finish with a word from their Master. “There are vile decencies,” said Rousseau.

Catholicism knows no such thing.

October 1, 1865.

Featured: Portrait of Jules Barbey d’Aurevilly, by Émile Lévy; painted in 1882.