It is with the sincerest gratitude to Monsieur Jean-Noel Freund, the son of Julien Freund (1921-1993), that we bring this first translation into English of “La peur de la peur,” an important essay on fear, published in Actions et recherches sociales. Revue interuniversitaire de sciences et pratiques sociales. Politique et insécurités. Le phénomène, ses consequences sociales, son impact sur le pouvoir, la mise en question de la démocratie (Éditions Érès: Nouvelle serie, vol. 21, No. 4, December, 1985). Thanks are also due to our good friend, Arnaud Imatz, for his unstinting, behind-the-scenes help.

We commonly understand security as that state marked by the spontaneous confidence which we feel, because we have the impression of being protected, not only from immediate danger, but also from the threat of some danger of some kind, which thus means that state in which we have no particular reason to be afraid. Conversely, we are unsurprisingly referring to the state in which we live in fear or under the threat of fear. The correlation between fear and security, or respectively insecurity, thus passes for a commonplace, both in popular opinion and in philosophical reflection. We conclude that we must try to push back and even banish fear from human relations, and we justify this rejection on moral grounds: It is a degrading and demeaning emotion from which individuals and societies should be exempted. One of the ways of conceiving freedom lies precisely in the relaxation of movements and opinions free from all fear.

Such a generally shared belief cannot rest on an illusion; it undoubtedly corresponds to aspects of the lived experience of men. God knows how often I have referred to experience; but I grant it epistemological validity only on condition that it is integrated into a critical reflection. There can therefore be no question of revoking the correlation between fear and insecurity. I just wonder if it is as well founded as it is generally claimed, and especially nowadays where, to make it appear that we are evacuating fear, we have put in place systems of protection of all kinds. Thus, we have instituted insurance and social security in order to relieve man of the fear of misery and the fear of the unexpected; and we have endowed authority with judicial and police resources for public safety.

Ever since Hobbes and Spinoza, modern political thought rests on the idea that society and the law are instituted in order to dispel fear. Spinoza expressed this most clearly and most succinctly: “The civil state is instituted naturally to end general fear and dispel general misery” (A Political Treatise). The question I would like to ask is twofold: Can we completely free the individual from fear? And is it desirable to do so? Indeed, we also know from experience that fear is the mother of wisdom and that it can be an invitation to moderation and discernment. In addition, respect for authority and order is based on the fear of sanctions in the event of a violation of the rules. There is fear in any obeisance, whether it is sacred or temporal. If two current global powers remain cautious in their relationships, it is because they are afraid of each other, each with the means of effective deterrents. In effect, for forty years, peace has had as its foundation this reciprocal fear. One can multiply such examples. It appears that there is no need to speak only of the pernicious effects of fear because it also has beneficial, even stimulating effects.

If fear is at the origin of the constitution of societies and of their maintenance, it would perhaps be advisable not to eradicate it, because then one risks, in such an endeavor, to shake loose human associations, along with order, and those institutions which pass for as generous, such as, social security. This is why the correlation between fear and security, and respectively insecurity, is probably not as simple as it is generally suggested. Hence the need to first carry out a phenomenological analysis of fear, in order to be able to better grasp its implications for security and insecurity.

Fear is a spontaneous and vital emotion of being which, by its very nature, reacts to the conditions of its environment, whether they divert it, or alarm it. It is part of immediate reactions, just like laughter or tears, like attraction to things that make us happy, or aversion to those things that are repugnant to us. No one behaves perpetually in an identically immutable and unilateral manner in his reactions to the world and to others. This is a basic aspect of existence from which intellectuality often distracts us. In any case, as long as we have not taken into account this diversity of life, we cannot understand fear. Apart from a few rare authors, such as Alain, most of the others have adopted a rather depreciative and demeaning attitude towards fear, as if it constituted a humiliating reaction by deceit or a decrease in being. By way of a random reading, we notice that authors tell us that fear chains the individual to the point of making him captive; that it is a spontaneous degradation of consciousness; that it is a conduct of failure; or even an inferior behavior for its incapacity to handle superior or rational conduct. Let us simply quote this significant observation by Sartre: “Thus the true meaning of fear is revealed to us; it is a consciousness which aims to deny, through magical behavior, an object of the external world and which will go so far as to deny itself in order to annihilate the object with it” (Sketch for a Theory of Emotions). Like other authors, Sartre associates fear and flight, as if it only gave rise to this evasive behavior, as opposed to courage that is valued as worthy from the point of view ethics. Basically, the common point of all these descriptions refers to the current prejudice of the preeminence of intellectualized reason in relation to which fear obeys a coarse, even despicable, process. And yet, there is an animal in us.

To understand fear, one must first not throw disdain on the body, which it would be wrong to decry because it happens to quake and shudder. On this point, Alain’s analyses seem to me more relevant than those of other psychologists. He even sees in fear “the incipient state of all emotion, the background varies, unstable and rich in all our feelings without exception. There is no courage without fear, nor love without fear, nor, finally, the sublime without fear” (Les idées et les âges – Ideas and the Ages). By the movements that it provokes in the body, fear puts the mind on alert; sometimes in alarm. Like any emotion, it is a warning; and like any instinctive reaction, it fulfills a function in the service of the individual and the species. It is, as such, part of our physical and moral health. Indeed, whether we like it or not, dangers exist; and quite normally, by instinct of life, we try to avoid them, to remove them; and, if possible, to overcome them. The question is not whether the danger is real or illusory, since the reaction is similar in both cases; the simple threat is usually enough to shake us. Fear is thus the immediate reaction to a threat, whether it is a natural calamity, a possible accident, the challenge of disease or a social oppression which limits our freedom of movement or opinion. Why denigrate it by associating it unilaterally with flight, itself considered pejoratively, and assimilated to cowardice, as if flight were not beneficial on certain occasions?

The variety and modalities of fear are immense; from shyness to panic, including worry, agitation, terror, anguish, fright, dread, etc. It can be individual like simple apprehension, or collective like panic. Flight is only one of its consequences, because it can also lead us to face danger. In general, it disappears in confrontation or action. I cannot believe those who say they were never afraid. I am thinking of the first actions of the small group of resistant students from the University of Strasbourg, in March 1942, in Clermont-Ferrand. They were executed as the first direct act of the resistance, at the Place Chapelle de Jaude, a few meters from Place de Jaude, brought to light and observed by the police. Despite a lack of any real weapons, we attacked the L.V.F. We hugged the walls for fear of being spotted and discovered. Once the action was carried out, we fled through the adjacent lanes, for fear of being arrested. And yet, it took a certain courage to make this mockery of the police, in the midst of a population which, at that time, was hardly in favor of resistance. Why cover the retreat of someone who has just carried out an attack with a weapon, if not to conjure fear of danger? Later, when in the Alps, German mortar-fire caught us by surprise, we were afraid, at first, and did not respond with our machine-guns. What were the courage and fear motivations for my escape from the fortress of Sisteron? One does not need to be “in a situation” – to use Sartre’s expression – to see in fear nothing other than a magical behavior of annihilation. As far as I am concerned, I cannot seem to combine fear and courage. Will the escape carried out so as not to be sent to a concentration camp in Germany be a failure? It was a question of fleeing from a more considerable danger. Too bad for intellectuals in need of justification for their unfulfilled fears.

The feeling of security sometimes elicits reactions that are worse than those of fear, for there is false security just as there are false fears. It would not be difficult to illustrate this assertion, for example, by the state of mind which the Maginot Line aroused among the French, to the point of corrupting their perception of the real threat and the audacity of was confronted them. The debacle of 1940 ultimately gave rise, during the years of the occupation, to fear that did not stop growing. The alert state of fear often stimulates inventiveness and entrepreneurship, while security lulls us to sleep and deceives us about danger. Fear is ingenious, like the cunning of the weak, who manage to put the strong in difficulty. It would take too long to develop here the role of fear in religions, in the economy or in technology. I would like to limit my remarks to the strategic phenomenon of defense.

Clausewitz believed that offense, despite its grandiose initial successes, is doomed to failure if it is not backed up by defense. He considered defense as the strong element of a war, because it rests on “the fear of the sword of the enemy;” that is to say, on the possibility of reverses in the attack. It is that defensive fear counts with the fear of losing what was previously acquired, in particular the territory or the country of which one was the master before the offensive. In this regard, we could start a debate on the adventures of the revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, or on the last world wars; but also on the current Soviet strategy which plays on the defensive, to the point of passing itself off as a perpetually attacked state – to better place its pawns in its offensive advances. Since Lenin, who was an attentive reader of Clausewitz, Soviet Russia strives to make people believe that it is afraid, that it is threatened and even surrounded; and that it is only defending itself. Her security lies in this game of fear that she ultimately instills in others, who come to be afraid of scaring her.

There is much to be said about the role of fear in the development of strategies, the avowed purpose of which, whether admitted or not, lies in the security of possessions and conquests. I will limit my remarks to a permanent historical phenomenon; to that of fortifications, ramparts, fortified castles, bastilles and citadels; but also to that of the protectorates exercised over neighboring countries, still called satellites; and finally that of so-called intangible borders. The situation in the Middle Ages is typical for our purposes. The Roman Empire had built strongholds along the limes to prevent incursions by barbarians; while inside it, the Roman jurists had developed a legal system for deterrence within the framework of internal security. We must never forget the role of fear in the formation of the law, because this is an element of dissuasion in internal politics.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire, the feudal structure of the Middle Ages had no other alternative, in the absence of a sovereign central authority, than the construction of stately bastions and towns or ramparts around towns, both to combat the claims of a lord or a neighboring town, and the incursions of a hostile army or horde and which also intended to bring them all to reason. The repartitions with which the free cities surrounded themselves are significant in this regard; they protected the city’s franchises and preserved the inhabitants, formed into militias, against fear. The modern State, born at the end of the 16th century, has reconstituted a central power capable of ensuring internal and external protection. Richelieu’s policy was decisive from this point of view.

These marks are only quick indications intended to make us reflect on the affinities (apart from the causalities generally invoked) between fear and security; but taking into account the phenomenon of protection and that of the enemy. Beyond these constitutive elements of any society, they confront us with other phenomena, also linked to fear, such as those of refuge, sanctuary, harbor (port); that is to say, places where we hope to find support and help. I would be failing in the imperatives of historical probity if I did not draw attention to the analogies with the present situation, marked by the decline of the State under the pressure, on the right as on the left, of an individualism which is in decline, breaking down the barriers of protection and law, by appeasing the terrorism of minorities, by legal generosity for delinquency and by pacifist debility. All these attitudes have as a common denominator the ignorance of fear, not for ethical reasons, but purely moralizing, as it is true that we consider ourselves to become devalued beings if we give any importance to fear; while it remains, in spite of our reasoning intellectuality, a visceral reaction of our being. Ideas can be overcome for free, not by guts. The danger however sweeps away the purest intentions because it makes us aware of the fragility of our being, of which fear is the sign. It constantly checks us, because it is an inescapable fact of our nature. Any legal and political construction which conceals it is only a framework without a foundation.

It is quite true that fear can inspire unhappy and harmful behavior; but it is just as true that it can inspire the reverse – auspicious and upraising behavior. Fear is simply ambivalent. It can be the source of both cowardice and courage – temerity not being courage because it is presumptuous and does not measure threat or danger. Fear drives security, as it exudes feelings of insecurity. We did not insist on its unfortunate and detrimental effects, because most of the authors have underlined them; it seemed essential to us to make the other side better known. Fear seizes us unexpectedly; and it is as a spontaneous reaction that we must understand it without seeking to impose a priori the logical categories of contradiction, or the ethical categories of the honorable and the humiliating. Such a step in the analysis is not only prudent, but also relevant, because fear is an emotion which surprises us by its suddenness.

No human being can, at the moment when fear invades him, know in advance if he will be courageous, and stand firm; or on the contrary, if he will be cowardly and if he will flee and adopt the behavior of failure. How will we react to torture? Some will collaborate and “sit down at the table” at the first instance of a simple threat; others will remain silent until death. It is not only a question of temperament, but also of the conditions that arise; for he who has been lost in certain circumstances may become valiant in others. I can then overlook the behavior of a friend of mine who “gave” the names of some of my comrades to protect his parents and who, a few months later, had a heroic attitude even in front of the firing squad. Finally, we must remember the illegal immigrants, who lived for months under the pressure of being constantly on alert, and who felt relief on the day of their arrest which broke the spiral of fear, as they waited for it; and unfortunately, to have to face other fears of another order afterwards. In this area there is no foreknowledge, no matter the studies of psychologists. You cannot swear to anything until you fall into the grip of fear.

Fear is a moment of truth of being; and, as such, it has an immense metaphysical scope – it is for consciousness the sign of the vulnerability that man tries to ward off by technology, whether it is mechanical, medical, computer or other. Heidegger, in my opinion, missed the point. His conception of anxiety is only a representation of fear; which means that like all philosophies of representation, he tried to empty metaphysics. His philosophy is political in latency. Let us take political discourse of all stripes. It readily evokes security and insecurity (with different accents, depending on whether it emanates from the right or the left, from the majority or the opposition); but it directly avoids dealing with the problem of fear. It is as if politicians are afraid to talk about fear; it is the taboo of political eloquence, just like violence, thirty years ago, when I was writing my thesis on the essence of the political. Sociologically, however, there is an affinity between fear and violence, as they are both at the root of security and insecurity. In truth, it is not so much knowledge (or science of fear) that is essential; but the recognition of its ambivalence. Metaphysics is precisely the discipline which is based on recognition (being as being). Reality is not the norm in and of itself.

In fact, there is never total security; which means that even in a community that provides the best protection, fear remains, for reasons other than simply political. Because it is a normal and fundamental reaction of being, it is impossible to repress it radically. We can only domesticate it, like violence. Both remain on the alert in the individual and in society and take advantage of circumstances to manifest themselves with more or less intensity. The role of politics is to constrain them within certain limits in order to give citizens confidence in their habits to stray to their occupations and aspirations. In other words, the task of politics is to put in place adequate and effective institutions in order to generate and maintain confidence, a condition for internal harmony.

This observation is more significant than it appears at first glance – tamed violence is in a way an assumed fear. From this point of view, one can consider the finality of the policy in two ways: That of the maximum and that of the minimum. In the first case, it sets itself the task, following the lesson of Aristotle or Thomas Aquinas, of forging the common good. In the second, following the lesson of Hobbes, it is limited to guaranteeing protection. Either the citizens have the impression, founded or illusory, of being protected and at the same time they have the feeling of being safe, or they have the opposite impression and they feel insecure. As I have shown in L’essence du politique (The Essence of the Political), opinion is central in politics. The manipulation of opinion, whether it is propaganda, demagoguery or ideology, proceeds from this elementary perception. Acting on opinion is generally a game of fear – but without admitting it. Machiavelli made the observation, as usual with a disconcerting perspicacity for moralism: “To stop being afraid, men believe it is good to create fear” (Discourses on Livy, Book I. XLVI). Listen to the usual speeches – if the right comes to power… if the left comes to power, you will be deprived of this; that will be taken away from you; and so on. Therefore, it no longer seems necessary to describe further the correlation between fear and security or, respectively, insecurity. In politics, “making people believe” very often draws its arguments from “making people fear;” but by playing on the pejorative and depressing aspects and modalities of fear. We must now delve deep into the unsaid political discourse and the latent attitude of citizens who have the feeling of insecurity.

Like any emotion, fear arises from direct contact with the real, or what we immediately grasp as such, beyond the control and censorship of the intellect. The imagination infiltrates the body, which then undergoes the jolts. Security and insecurity, on the other hand, are mediated forms, represented, which have distanced themselves from fear and reality. They belong to the order of the imagination which tames the emotions by taking them away from the given reality. It is therefore a question of not confusing the imagination and the imaginary. The imagination is in the body, in its movements (recoiling or bunching up), to the point of immediately inventing specters, ghosts and other scarecrows. I can only refer to what Alain said on the subject (Définitions, or Histoire de mes pensées). The imaginary, on the other hand, is an ordered and intellectualized representation, whether it is a question of works of art, myths or utopias. It is no longer immediately associated with the real, but transposes the real intellectually, including in the muddled fictions of modern abstract art. Because of its immediate contact with the real, pain is neither secure nor insecure; it becomes so through the intermediary of the intellect. It is in this sense that security and insecurity arise from the imagination; that is to say, from the intervention of the intellect in the apprehension of fear. To express ourselves first very laconically, we will say that the feeling of security arises from a fear overcome, but not eliminated; the feeling of insecurity arises from the fear of fear.

Security is a neutralization of fear; not by excluding all fear, but essentially by reducing, as far as possible, that which risks weakening the order of a society, namely, the fear of violence.

Security is fundamentally political, and it is only in the second degree that it also concerns the economy or the social. The person who has illegitimately resorted to violence passes for an enemy in the full sense of the term; that is to say, the individual or the community who threaten our physical or moral integrity. It may happen that for reasons of expediency (demagoguery or moralism) politicians give priority to secondary forms of security; but as soon as there is a threat or danger to life, protection from violence comes to the fore, in correspondence with the finality of the political. Bad politics, including from an ethical point of view, is on the one hand that which uses violence or terror against the people it should protect, and on the other hand, that which cheats with the priorities. Insofar as law, understood as a set of rules but also as a judicial and police body, is a major deterrent, it is dangerous to play with constraint and legal firmness, even in the name of the best intentions. No doubt, citizens expect power to improve their conditions – but above all they want that this power protect them from the radical danger of death by violence. What is the good of guaranteeing the comfort and common conveniences if one cannot enjoy them freely, because one must constantly fear for one’s life? Politics, insofar as it is the body for the protection of the community against arbitrary and savage violence, responds to an elementary imperative, in relation to which the other demands certainly appear to be desirable, but incidentally.

Let us try to comment as quickly as possible on this presentation of the principle of safety. It is characterized by the domestication of violence, without however seeking to suppress the individual and spontaneous fears of being, which belong to its sphere of freedom, such as anxiety, agitations, aversions and repulsions that one experiences in his ordinary life. These fears are part of the idiosyncrasy of every being with varying intensities and frequencies. There is no need to revisit the positive aspects of fear, developed above, which activate human industry. The fear of violent death is of another order. We may regret it, but the need for security is so powerful that people sometimes sacrifice their freedoms for security. There is no shortage of examples of this kind of collective behavior, including in contemporary history. Human beings go so far as to submit to despotism, of which Montesquieu rightly said that it is the government which has fear as its principle (The Spirit of Laws). It is not with moral adjurations that we will deter people, because the concern for security seems to them primordial.

We come up against the thorny problem of freedom and security, which is less delicate than it is generally said, on condition that from the outset we do not resort to sanctimonious discourse. Indeed, the debate is often false because, for two centuries or so, we have made for ourselves a primarily moral idea of freedom. Until then, freedom was first conceived of as a state, a way of being for man in society – freedom characterized the individual who, in his state, was neither prisoner, slave nor serf, nor a simple subject, but who enjoyed definite prerogatives in a community jealous of its franchises. Considered as an ethical virtue, freedom becomes the object of an indefinite quest, without completion.

When we consider freedom not as a state, but as an aspiration, we run the risk of never enjoying it in empirical reality, since power can constantly postpone the conquest of total freedom to an indefinite future. It is in the name of total liberation in the future that people are deprived of formal freedoms in the present. Either the policy grants, or grants citizens, the state of freedom as an element of their individual and collective security; or it conceives it as an idea to be realized in the future; and it abolishes the freedoms on the ground. We believe that we have said everything about the opposition between so-called real freedom and formal freedoms by imperturbably repeating Marx’s formula, while sociologically formal freedoms are part of the inevitable imperfections of any society. In a sincere democratic regime, the citizens actually benefit from them, while in totalitarianism they remain in perpetual waiting for them. The error consists in hoping for freedom of only the political kind; whereas freedom is a condition of exercise of all activities, economic as well as scientific or artistic. It is up to the politician to establish a state of freedom, so that other activities can in turn cultivate it according to their own standards and genius; without those who use it, having to fear for their physical or moral integrity. Therefore, security does not only have a purely police significance; but its task is to preserve freedoms – which means anticipating, through foresight and prevention, threats and dangers that could deprive us of it.

Insecurity arises from the loss of trust in institutions designed to protect members of a community. There are many reasons for this kind of fear: The nonchalance of the authorities in the application of laws and sanctions; the slowness of justice; the moral or ideological hesitations to use the weapons of repression; the propagation of diffuse and gratuitous violence that can be observed in the field, despite the theoretical assurances given by certain sociologists. I have developed these themes elsewhere; we can summarize them thus: The law ceases to be dissuasive. This deficiency suggests, if it worsens, the appearance of an anomic situation. Truth be told, there have been other anarchic periods in history, the most memorable and longest having been that of the Middle Ages. The means of guaranteeing security then was self-defense, in the form previously mentioned, that is, strong castles where the population could find refuge in case of danger, or that of ramparts and towns. The modern state put an end to this situation by establishing general security by prohibiting recourse to private violence and by seizing the monopoly of public violence, as the only legitimate one. Without dramatizing the situation, today we can speak of a crisis of the State, to the extent that, contrary to its original function, it is failing in its protective mission in the face of the return of private violence and in the face of terrorism by underground groups (La crisis del Estado y otros estudios, which only exists in this Spanish edition ). To add insult to injury, some states are accentuating this crisis by organizing government terrorism. Fear for life is re-awakening the instinct for self-defense as a means of combating insecurity.

It cannot be said that we are already a living in anomic insecurity; but repeated failures in protection have created a feeling of insecurity. This feeling is not generated by fear, but by fear of fear. This has a special character, because it is no longer a question of fear in the proper sense of the emotion which suddenly arises in the face of an immediate and unexpected threat; but a fear which becomes its own object, apart from all direct danger. It is a diffuse fear just like the danger it supposes. It should not be confused with an extreme fear in the sense that, for example, the joy of joy and the voluptuousness of voluptuousness designate joy or supreme voluptuousness, but with a kind of fear sui generis. It is a fear of a kind different from that which is usually analyzed. It protects itself less against violence than against fear itself, which it considers only in its catastrophic aspects. Everything takes place in the imagination, which feeds on the representation of possible dangers and eventual damage, with a sort of psychological preparation of the actions that will be taken to respond. It is an obsession maintained by individuals that can turn to psychosis: Being is on the lookout; it watches and monitors the environment, jumping at the noises it keeps evoking and repeating in the imagination. There is no doubt that the ambient relative insecurity amplifies this fear of fear, sometimes to the point of phobia. Being lives in love with its fear; the latter becoming proof of the legitimacy of its fears. By dint of reshaping our fears in the imagination, self-defense, in the event of a qualifiable aggression, turns into self-defense no matter what the circumstances. All it takes is one incident to trigger the series of reactions constructed beforehand into the unreal, often in the context of an angry rage, and its end fed by information concerning the various facts. The fear of fear mocks reasoned analysis: It is itself its own criterion. The problem lies in the shift from self-defense to legitimate defense. Self-defense arises in the context of a right which is not respected or is ideologically accused of being an obsolete constraint; self-defense, on the contrary, is a reaction in a legal situation characterized by the lacuna or the occurring powerlessness of the law.

The description I have just made obviously relates to cases of individual self-defense, which risks proliferating, if the climate of insecurity turns into contagion. I would like to emphasize in this connection one other point that current sociological theory generally neglects. It focuses on urban insecurity, perhaps because the great majority of sociologists are city-dwellers, accustomed to the concentration of the population which, in itself, gives more volume and latitude to surveys. Living for several decades in the countryside, I have observed over the years the slow deterioration of the feeling of security in the villages. I could relate here many observations, for example, the suppression in all the villages of my canton, without any exception, of the annual festival organized traditionally by the municipalities, because they ended regularly, latterly, in violence. I was giving, some time ago on a Saturday morning, a presentation in Paris on diffuse violence and I expressed the idea that, under the current conditions, one must expect serious disturbances in my town during the night. Going home the same evening, I was told about the gunshots exchanged the night before which, fortunately, had no other consequences than wounding. In any case, my observations lead me to disagree with the sociological literature on the violence of city-dwellers and on violence in general. I limit my remarks to evoking these two examples, because the essential problem is that of fear of fear, which politicians and lawyers seem to ignore.

The question is not only about the more or less effective measures of protection and alarm that the inhabitants take to protect themselves against insecurity; but on a phenomenon which seems to me much more pernicious: The absence of confidence leads to fatalism, full of unsuspected revolts. The danger posed by fear of fear does not lie only in cases of self-defense, amplified by the media, but in the resignation of beings who feel they are being cornered. Social fatalism is like a flat sea waiting for the storm. If the circumstances are favorable, the accumulation of anger and internal indignation risks transforming the fear of individual fear into unreasonable collective movements, during which the fear of fear escapes. I saw young guerrillas, who had just been informed of a possible attack by German troops supported by a few tanks, rushing about with their submachine guns and firing bursts indiscriminately; they acted under the pressure of fear of fear. Many reactions from the crowd in the immediate aftermath of the Liberation were only a way to free themselves from the fear of fear, endured only for a few months. History tells us of multiple uprisings and mutinies which have had their source in individuals who earlier were suffering the fear of fear.

The fear of fear, once it subsides, is often cruel. Thus, in the aftermath of the Liberation, it was not those who had long participated in the resistance, those who were the perpetrators of numerous attacks, who showed themselves to be the most vindictive and ferocious, but the anonymous and apparently peaceful, who were left out of the coup, and who thus freed themselves from the fear of fear accumulated during their abstention and sometimes in their cowardice. In a completely different register, the hostages, prisoners of the reduced space of an airplane, manage to excuse the behavior of the pirates who are their jailers and attack those from the outside who have abandoned them. This is at least partially a reaction of the fear of fear, which they are thus trying to ward off. Moreover, one of the objectives of the acts of piracy, and more generally of terrorist attacks, is to spread fear of fear among the population and to provoke a destabilization of society by making reign the feeling of insecurity.

It goes without saying that since fear plays, as we have seen, an important role in politics, the fear of fear is one of the temptations of power. In any case, it is one of the weapons of dictatorial regimes, because it makes it possible to paralyze the reactions of the citizens. Stalin made particularly cynical use of it, since he stirred up trouble even within the ranks of the party by arresting, deporting or liquidating not only ordinary members, but the firebrands of the regime, since one who did not fully approve of all the measures he took, became a real or potential enemy. It is the method of “the permanent purge” which, to prevent those eliminated passing for heroes or martyrs, demanded of them a self-criticism, relating their so-called failings (The Principles of Power). The whole system was based on the fear of fear of betraying the party.

G. Ferrero believed that the fear of fear was not unique to dictatorial or despotic regimes alone, but that it is inherent in all power, and especially in our time, torn by the rivalry of the principles of legitimacy. Man is not only afraid, but he is afraid of the fact that he may frighten others. Such is the circle of this fundamental emotion. The animal only uses its body, while man also uses instruments, some of which are precisely intended to be frightening – weapons. The remarkable fact is that these are of an offensive and defensive nature, like the spear and the shield. Fear is correlative of the one and the other. In addition, the technical faculty means that man has the capacity to make designs which, in turn, can be offensive or defensive. Power, because it is exercised by men, does not escape this fate; and it is all the more exposed to the fear of fear as “history is only a series of revolts, attempted or successful, against Power, and of efforts to prevent these revolts. Power is never secure; it trembles constantly; it scares itself as much as it scares others.” The fear of fear has a double face: Fear for itself and fear of others. It commands all power: “There may never have been, there will never be, a Power which is absolutely sure to be always and totally obeyed. All Powers have known and know that revolt is latent in the most submissive obedience, and that it can break out one day or another, under the action of unforeseen circumstances” (The Principles of Power).

This fear of fear, immanent in all power, has expanded in modern times from the conflict between the principles of legitimacy. Monarchical legitimacy was hardly called into question until the eve of the French Revolution; the usurper became king and thus perpetuated this type of legitimacy. Since the French Revolution, various principles of legitimacy have been competing for the right to power and obedience. Two seem essential to me: Monarchy or quasi-monarchy, in the form of a modern dictatorship, and democracy, itself divided into liberal and revolutionary regimes, the latter applying the democratic principle in the wrong way and backwards. Ferrero quotes in this connection a passage from De I’esprit de conquete et de la usurpation by B. Constant: “Fear, then, comes to mimic all the exteriors of courage, to congratulate itself on shame and be thankful for misfortune. A singular kind of artifice indeed, of which no one is fooled! A conventional comedy, which imposes itself on no one, and which for a long time should have succumbed to ridicule! But the ridiculous attacks everything, and destroys nothing.” The consequence is that, under the fire of revolutionary polemic criticism, democracy ends up being afraid of itself. It is afraid of never being democratic enough. Thus, democratic power, which seems the most legitimate nowadays, enters the cycle of the fear of fear – it becomes suspicious and distrustful not only in matters of internal policy, largely in the social domain, but also in its international dealings, where, out of fear, it accepts forceful coups. It thus comes to seize upon fear, and itself ultimately comes to practice fear – July–August 1940!

If fear is intimate with our being, because it torments the body, and through the fear of fear it disturbs the mind through the power of the imagination, it should be taken into account in our understanding of justice. This has other aspects than those which intellectual fashion currently stresses, if only because the feeling of insecurity takes root in the impression of the deregulation of justice. Our century, which gives primacy to intentions about consequences (hence the idea about experience), is in want of justice. Ordinary political discourse indirectly proves this: All politicians have this word in their mouths; they compete in rhetoric about it and proclaim that they want to work for justice, which suggests that it is lacking. Could this lack not be due to one-sided twaddle bereft of consequent conceptual reflection? In fact, all this happens as if men were in service to an abstract justice, pure of intention – whereas justice should be at the service of men to settle their embarrassing, sometimes wicked, often conflicting empirical relationships. The idea of justice of pure intention, which currently prevails, at best tries to eliminate fear; whereas the other justice, in service to men, in particular in the form of the fear of fear, is based on the necessity of justice. Where fear disappears, justice will become useless. What is the use of justice where men live in harmony, in good understanding, sheltered from all fear and all threats?

All thinkers, from Aristotle to Max Weber, who have taken the trouble to examine the concept of justice in its depths and its implications, instead of using it as a slogan, have recognized that it is not unequivocal. Let us limit ourselves to considering Book V of the Nicomachean Ethics, because it brings to light aporias that only ideological phraseology claims to be able to overcome. Aristotle remarks that there are several kinds of justice which cannot be reconciled, because they are not reducible to one another. The history of thought designates them as distributive justice, restitutive justice and commutative justice. There is no need to go into the details of these distinctions which any good manual of philosophy or law explains to us. Justice concerns all relations between men, whether it is about the merit or the creative capacity of some which is greater than that of the others, and therefore of the inequalities which follow; or of the redress of material or spiritual damage that one inflicts upon another; or even of the proportion between rewards and services, between competence and negligence; or finally between obedience of the law and the aspirations of disinterested devotion. If we limit ourselves to the canvas of egalitarian justice, what should be done? To reprimand gifts and talents, to lower them to the level of general mediocrity? Or, on the contrary, to stimulate the creative force of engineering whose products can raise the general level? We cannot, observes Max Weber, give a “definitive solution” to this antinomy, intrinsic to the concept of justice. There is a risk of damaging one of the representations that men honestly and in good faith have of justice, while taking advantage of it.

Aristotle believes in addition that it is even necessary to correct justice so that it becomes just. He holds this empirical revision of abstract justice to be fair. The law has the advantage of introducing regularity, and therefore a rationality and a rigor, which can be controlled, in the relations between men. But, he notes, the practical order takes on a character of irregularity which is not necessarily morally condemnable. Charity can gut justice. But should it be rejected for this reason? Love is often enough at odds with justice. But would it be fair to denounce it? In any case, love cannot be reduced to justice; it is of another order. Would it be fair to ignore the difference between human orders? The function of equity [in the jurisprudence sense – not in its current, progressivist sense – Tr.] is precisely to restore justice in conflicts between types of justice which are at most reconcilable only in intentions and pure ideas. It introduces arbitration to concretely overcome the aporias of justice. Is it fair that the victims of burglaries, assaults or scams refrain from filing a complaint for fear of having to defend themselves of having been robbed, sometimes of being accused, because they are the victims? They pass for being fools, because the justice of the strongest, including through lawyers, is not only a usage by humanity in primitive times. The feeling of injustice experienced by the weak is just another manifestation of the fear of fear; and it fuels the feeling of insecurity. It would take too long to produce here the cases of resignation which are in the process of multiplying, if we wish to make observations on the ground. In other words, the fear of fear is indirectly a claim against failing justice, administered in injustice, so that weariness often ends up fueling revenge. We are at the heart of the aporias of justice – is it pure convention or does it also obey an internal voice? It is about the old debate still current between nature and the law.

Our era favors a particular kind of justice: social justice. All other species are considered lame if they do not support or flow into this form. However, social justice can, in some of its aspects, engender inequities because, according to the formula of Bénéton, the good can become a plague. There should be nothing scandalous about this kind of observation, as long as one takes the trouble to understand the concept of social justice. It is a question of justice external to beings, because it concerns the social order and the material conditions of existence, presupposing that, if this order is just, individuals would become so as a consequence. It appears all the more commendable when it is put directly in connection with security, under the guise of social security. It is indisputable that social security delivers the well-to-do from a particularly dramatic fear of fear – that which precipitates people in poverty following, for example, a health accident or setback in the trades. It is therefore necessary to put to the credit of modern society the organization of an indispensable system of social security, although it gives rise, like any human institution, to the fraud of profiteers, to abuses and to perverse effects, like those of the welfare state. These are drawbacks that must be taken care of, because no human affair is exempt from them.

I would like to focus the discussion on the current tendency to see in social justice not only supreme justice, but in addition the justice which can only be really just. Indeed, the current discourse tries to make us believe that the solution of the social question would be the achievement of justice as such. This is no longer a virtue which depends on our will and the putting into practice of norms, but it is only the reflection of the material conditions of existence. In principle, it is an eminently legalist justice, because it calls for conventions and legal texts, which constitute the reference for any initiative in the social order; it does not matter whether we reason in terms of reforms or revolution. The goal is to make society fair and no longer require individuals to be fair in their conduct. This way of seeing things confronts us with the main aporia: Is justice to be achieved by impersonal conventions in accordance with its abstract idea of justice, or does it also reside in the acts that we perform correctly in the contact with others? Should men bow to the just or unjust order? Worst comes to worst, a person no longer has to behave according to the standards of justice, because that becomes superfluous in the context of an order installed in justice. Is it not a question of the order of utopias which claim to regulate in their imaginary paintings not only the problem of fear, but in addition to dispel all the reasons for seeing fear? And yet, as I showed it in my work, Utopie et Violence (Utopia and Violence), all utopias institute a police regime in order to prevent those who benefit from such just laws and institutions from falling back into their old troubles and mistakes. The police remain the only guarantor against the return of fear – but by arousing the fear of the so-called conquered fear.

In all probability, it is not social justice, conceived a priori as the development of a just social state, regardless of circumstances and men, which can eradicate the fear or fear of fear; it can only constitute a contribution to relative security. Since this stems from the confidence in the protection provided by the army against the external enemy and by the police against violence and the internal enemy, security depends on prevention. A security which is not at the same time prevention loses all consistency and even all meaning – it is prevention or it is nothing. It is for this reason that we must not play intellectually with the phenomenon of prevention, by considering it as one in itself, sufficient in itself; that is to say nowadays as the new method, which is replacing the old and bygone methods of repression and deterrence. These are, on the contrary, part of the system of preventive measures. It is through lack of confidence in these new formulations of primarily rhetorical prevention that the feeling of insecurity tends to become contagious. Error consists in standardizing justice to one of its types, whether it is distributive, social, commutative, reparative or corrective justice. It must be taken with the aporias which are inherent to it, which it is not possible to reconcile, because of the antinomies between the feeling experienced and the artifice of conventions. More exactly, one cannot escape the trade-offs of equity. Is it right that people fear for their safety? The best intentions of lawmakers remain powerless if confidence is disturbed. Thereafter, the feeling of the fear of fear will pervert the feeling of insecurity by inducing individuals to take justice into their own hands, sometimes in the form of revenge, most often by justifying self-defense as legitimate defense. It is not just that individuals take revenge by listening only to their arbitrariness; but it is not just either that they are reduced to suffer injustice in their person, in their ideas or in their property, so that they can only rely on judicial apparatus and institutions.

Security is as much a matter of feeling and trust as of materially organized protection. Equality in justice only really makes sense in the case of protection, insofar as all citizens are equal before the law; on the other hand, the sentiment is not egalitarian. The basic problem is ultimately that of objectivity and subjectivity, which in turn poses that of equity. From this point of view, the modern debate between objective law and subjective law contributes to confuse ideas, to the extent that we precisely seek to introduce equality into subjectivity, whereas by its nature it is rebellious. Nothing highlights this confusion more than the discussion of the law of retaliation, which is presented as justice for revenge; therefore, as a barbaric law which corresponds to the primitive mentality of mankind. It is a safe bet that those who use this language have only superficially read the Book of Exodus. The law of retaliation is a law of objective law; and undoubtedly the only possible egalitarian one, because it establishes a compensation between objective acts and not between subjective intentions. All the measures taken to circumvent the objectivity of this law are fundamentally unequal, for there can be no equipollence between intentions, without abolishing subjectivity itself.

Let us therefore read the passage from Exodus. It is true that it declares: “Life for life, eye for eye, tooth for tooth, hand for hand, foot for foot, burning for burning, wound for wound, stripe for stripe” (Ex.21:23-25). But it also specifies: “If any man strike the eye of his manservant or maidservant, and leave them but one eye, he shall let them go free for the eye which he put out” (21:26). And again: “If one man’s ox gore another man’s ox, and he die: they shall sell the live ox, and shall divide the price, and the carcass of that which died they shall part between them: But if he knew that his ox was wont to push yesterday and the day before, and his master did not keep him in: he shall pay ox for ox, and shall take the whole carcass” (21:35-36). Only equity is objective because it balances material acts that can be identified. Understood in this way, the text means – an eye for an eye; but nothing but an eye, and no more than an eye. If we deviate from this strict fairness, the judgment becomes subjective. This means that both mitigating and aggravating circumstances are of the order of inequality. Equity is the form of justice which strives to counterbalance objectivity and subjectivity, equality and inequalities. It is not a question of depreciating subjectivity or attenuating circumstances; but only to permit the recognition that subjectivity introduces unequal procedures and that it cannot be invoked in favor of an egalitarian justice.

The lesson of the law of retaliation seems to me to be the following: It is necessary first to have the idea of egalitarian and objective justice, bearing on the comparison of ascertainable acts, to be able to involve the justice of equity; which means correcting the stiffness of egalitarian justice by introducing inequalities which humanely rectify the abstract rigidity of pure justice. If we begin by rendering justice by taking into consideration only the subjectivity of the motives, in the absence of the prior recognition of the objective equality of acts, justice ceases to be humanly just and becomes an often unfair lottery between inequalities, each time appraised differently. The justice of lawyers is often more iniquitous than that of judges; unfortunately, judges are increasingly becoming advocates of an abstract cause and no longer arbiters in equity. Only equity as an arbitral judgment is likely to curb the duties of a law that is purely subjective. The law of retaliation at least implicitly recognizes this role of equity: “If men quarrel, and one strike a woman with child, and she miscarry indeed, but live herself: he shall be answerable for so much damage as the woman’s husband shall require, and as arbiters shall award.” The text of Exodus seems fairer to me than all modern theories of justice.

The absence of an objective point of reference has the effect not only of generating new injustices, but of creating a feeling of insecurity by fueling fear of fear. The imagination goes crazy when it loses all contact with any objective reality. Until now, I have only illustrated the relationship between the fear of fear, subjectivity and the imaginary when it comes to law. It is clear that it is found in all other spheres of activity. I will mention at the end of this study, very briefly, only one other example that I am reserving to develop at greater length in another article devoted to the press and the media. In these cases, it is no longer a question of an insecurity which settles, for lack of lucidity, in the hearts of men with good intentions, but of the fear of fear deliberately maintained with a view to destabilizing a society. In other words, the fear of fear is sought knowingly, I stress – knowingly – with the supposedly revolutionary goal of a transformation of social structures and of the regulatory elements that are laws and mores. It goes without saying that this cynicism slips away, as always, from a moralism that is all the more boisterous as it is both insinuating and more brazen. Lenin misleads even those who have not read him, perhaps because they have not read him, starting with those who claim to be his.

There are journalists who launch rumors which they know to be manifestly false, with the intention of cowardly discrediting opponents of their personal options and at the same time confusing their readers or listeners by slowly instilling in them the fear of fear by usurping their trust. I am thinking among others of an example that I know particularly well of a few authors who have been called into question in the most hypocritical and treacherous manner. One of them died almost a century ago. While these authors are known for their hostility to terrorism, they have been accused in the press of being the clandestine instigators of recent terrorist attacks, no doubt to protect the genuine terrorists by deflecting suspicion from them. What is deplorable in this case is that certain court sentences tend to wash away these journalists of this type of disloyalty, on the pretext that they are not bound, like historians, by the rule of objectivity concerning the facts they relate. I will add only one very quick reflection: the injustices thus committed in the name of partisan subjectivity risk being covered by the judicial authorities, under the pretext of a justice never defined in its implications.

One of the essential sources of the fear of fear and the feeling of insecurity is to be found in the derailments of the judicial system which, in the name of good intentions, disfigure the nature of prevention; or else which, for intellectual corruption, cover with the mantle of justice the arbitrary subjectivity of injustices. Responsibility is not for intentions, but for actions and their consequences. The almost systematic denigration of the notion of objectivity and of one of its parameters, which is critical experience is, it seems to me, the metaphysical source of the feeling of insecurity. It is true, in the name of subjectivist individualism, metaphysics has also been discredited as a discipline which bears on being as being. However, fear is an inseparable dimension of being. The metaphysical depreciation of fear leads people into social instability and insecurity by installing them in the creeping and distressing fear that is the fear of fear. It takes the place of an illegal standard of justice where fairness is lacking.

Translated from the French by N. Dass.

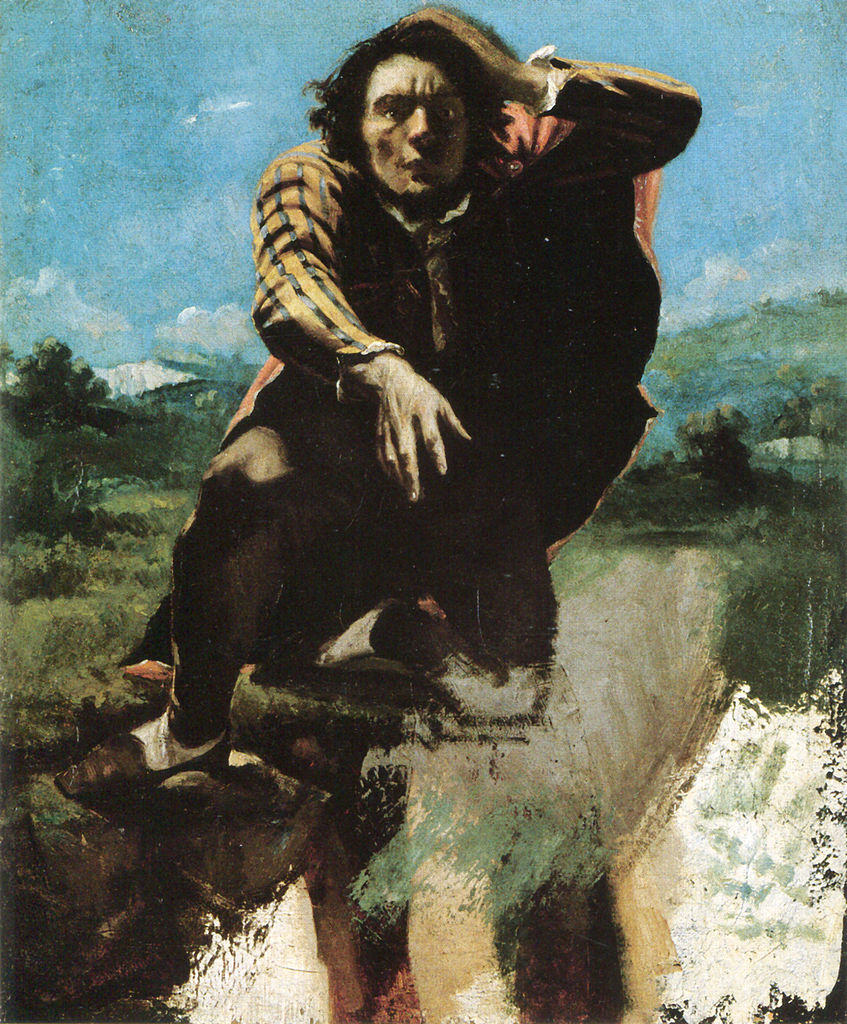

The featured image shows, “The Man made Mad with Fear,” by Gustave Courbet; painted ca. 1844.