Directed by Murnau in 1922, Nosferatu is one of the great masterpieces of German expressionist cinema. Contrary to what some may have believed, it has no connection with the rise of Nazism, but undoubtedly reveals the trauma of the Great War and the Spanish flu.

In 1838, in the northern port of Wisborg. Thomas Hutter (Gustav von Wangenheim), a young real estate agent, is happily married to the beautiful Ellen (Greta Schröder). Without worrying about her dark premonitions, he leaves for Transylvania to sell a residence to Count Orlok (Max Schreck). In a tavern, locals tell him that the Count’s castle is possessed by dark forces. Nevertheless, he goes there. But as soon as he crosses the bridge, ghosts come to meet him.

When he arrives at the castle, he is welcomed by the sinister Count. During the negotiation, Orlok sees an engraving of Ellen and decides to buy the building near the couple’s house. At midnight, Hutter cuts his finger:

“Blood! Your precious blood!” exclaims Orlok before sucking his finger.

At night, the Count prepares coffins of Transylvanian soil, to take to Wisborg. Hutter then understands the true nature of his host: a vampire who, at night, feeds on the blood of his victims.

Nosferatu, after a long sea voyage, during which he exterminates all the crew, spreads in the city of Wisborg an epidemic of plague. He takes possession of his new house, located opposite the Hutters’. At night, he watches and covets his next victim: Ellen.

Ellen learns that the only way to defeat a vampire is to expose him to sunlight. To save the plague-stricken town and ward off the curse, Ellen lures the vampire into her room and sacrifices herself. The sunrise catches her there. The vampire Nosferatu crumbles to dust.

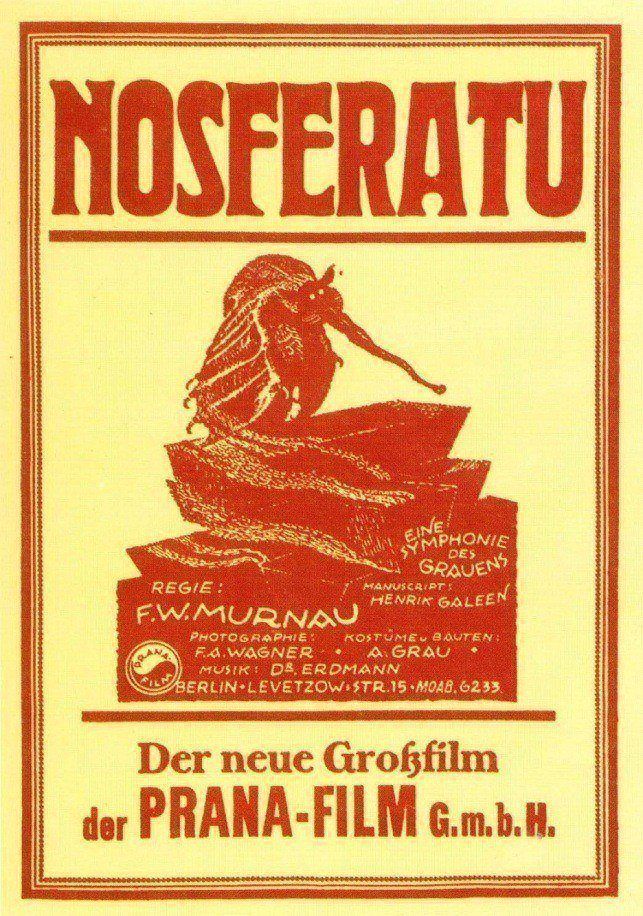

Nosferatu (Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens [A Symphony of Horror]) is a German silent fantasy film, directed by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, was released on March 4, 1922.

The limited budget of this film did not allow for the acquisition of the rights to the novel Dracula by the Irish writer Bram Stoker, which was published in 1897. However, Henrik Galeen’s screenplay was strongly inspired by it, while taking several liberties: the action takes place in the imaginary city of Wisborg (instead of London), the names of the characters are changed from the novel, Dracula becoming notably Count Orlok (Nosferatu). Galeen also adds to the original work an idea that will mark the myth of Dracula: daylight can kill the vampire.

Nosferatu was the subject of a lawsuit brought by the writer’s widow. In 1925, a judgment was passed, requiring the destruction of all illegal copies. However, several copies remained in the United States and in France.

Nosferatu was filmed in real settings, which was rare at the time. The filming took place in Slovakia, in the Carpathians, for the scenes that were supposed to take place in Transylvania. The castle of Orava is used as a set for the castle of Count Orlok. The interpretation is uneven. It is regrettable that Gustav von Wangenheim plays Hutter with an enthusiasm that borders on the ridiculous. Greta Schröder is more convincing when she plays Ellen resigned to sacrifice herself.

A century after the film’s release, the actor Max Schreck continues to leave his mark. Long and rigid, with long, hooked fingers, a pale and frightening face, a bald head, thick eyebrows, and an obsessive gaze, he plays a particularly horrific vampire. Murnau’s vampire is different from the character of Dracula portrayed in later adaptations, notably the 1931 adaptation in which Bela Lugosi plays a mysterious and refined vampire.

Expressionism is evident in Nosferatu’s oppressive close-ups and the play of light and shadow, as well as in the hues Murnau used to color the film, giving the illusion of alternating day and night. The soundtrack, composed by Hans Erdmann, further accentuates the dramatic tension.

The acting of Max Schreck and the expressionism make this film one of the great masterpieces of silent cinema. Thus, according to Jacques Lourcelles, it is “one of the five or six essential films in the history of cinema, and without doubt the most important silent film… Nosferatu is above all a metaphysical poem in which the forces of death have a vocation—an inexorable vocation—to attract to themselves, to suck in, to absorb the forces of life” (Jacques Lourcelles, Dictionnaire du cinéma). Murnau thus shows evil in its purest form, Nosferatu living in darkness and sowing plague behind him. Of course, this film was not conservative at the time, since it was devoid of any religious connotations. But Ellen’s sacrifice to eradicate evil is in line with such meaning.

Many film historians have believed that they can make a connection between this terrifying Weimar-era film and the rise of Nazism. In his book, From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film (1947), Siegfried Kracauer attempts to show that Nosferatu, by showing Ellen’s attraction to the vampire, helped bring Hitler to power in Germany! Anton Kaes even sees “anti-Semitic motives” in the images of rats spreading the plague, or the fact that Nosferatu comes from Eastern Europe, like the “Eastern Jews” who migrated at the end of the 19th century! Bardèche and Brasillach saw in Siegfried Kracauer’s essay “a strange desire to politically distort the facts” (Bardèche and Brasillach, Histoire du cinéma).

Indeed, since this film dates from 1922, it is simply an allegory about the collective fears caused by past traumas—the First World War and the epidemics in Europe at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, such as the Spanish flu (from which there were 426,000 deaths in Germany).

Kristol Séhec writes about culture, film and comic books. This article appears courtesy of Breizh-info.

Featured image: “Nosferatu,” one sheet poster by Albin Grau (1922).