Historian Miguel Platón has researched all the death sentences handed down by the military courts of the Franco regime up to 1975 and thus has an in-depth knowledge of the extent of the post-Spanish-Civil-War repression, as well as the crimes of which the defendants were accused. In this article he reveals the evolution of the prison population and the legislation in this regard, which confirm the non-existence of genocide. Another lie that he refutes is the claim of the existence of more than 100,000 bodies abandoned in graves.

The political objective of the Law of “Democratic Memory”(October 19, 2022), presented by the Socialist-Communist Government of Pedro Sánchez, is similar to that of the Law of “Historical Memory” promoted in 2007 by the Socialist Government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero—to hide the responsibility of the socialist trade union and party (the UGT and the PSOE) in the failure of the Second Spanish Republic (1931-36), a period in which the leftists resorted to the use of violence, including an armed rebellion against the Government in October 1934, the manipulation of the outcome of the February 1936 parliamentary elections and the cover-up of the assassination of a right-wing opposition leader, Deputy José Calvo Sotelo (July 13, 1936), by a Socialist gunman. It also seeks to conceal the crimes carried out by the leaders and members of both organizations during the war: tens of thousands of murders, tortures, rapes and robberies; and, last but not least, the corruption of several of their most prominent leaders.

The legal initiative constitutes, above all, a betrayal of the combatants of that war. When the Spanish Civil War ended in April 1939, both armies had around one and a half million young Spaniards between eighteen and thirty-two years of age in their ranks, the great majority of whom had been forcibly mobilized, since volunteers represented only ten percent of the total number of combatants. Tacitly but firmly, these young people set themselves a fundamental political goal, which they maintained for the rest of their lives: never another civil war, so that their children would not endure the suffering they had endured. The goal would be achieved and, together with economic development, was the basis of the Spanish political miracle of the late 1970s: a broad social consensus that opened the doors to democracy, crowned by the 1978 Constitution. The breaking of that consensus by the PSOE leadership means promoting the return to a polarized society like the one existing in 1936, which led to the greatest tragedy in the history of Spain.

The Republic: A Regime of Permanent Violence

The political violence linked to the Spanish Civil War comprised three phases: before July 1936 (the beginning of the war), during the conflict (from July 1936 to April 1939) and the post-civil-war period. The three followed one another with varying intensity, but in practice without solution of continuity.

The recourse to violence was born at the same time as the republican project. The conspirators, who in August 1930 united to overthrow King Alfonso XIII, formed a Provisional Government which, in turn, appointed a Military Committee, with the express purpose of organizing an insurrection. Most of the conspirators’ economic resources were used to buy pistols, and in December a double plot was planned: a coup d’état by related military units and a general revolutionary strike. The latter failed due to lack of union collaboration, but military commanders rose up in Jaca (Huesca) and Madrid. The first proclamation, published in Jaca by a captain of the Army, read as follows: “Anyone who opposes by word or in writing, who conspires or arms against the nascent Republic, will be shot without trial.”

It was not an idle threat—a little earlier the rebels had killed the temporary chief of the Civil Guard and two carabineros. In the twenty-four hours that the uprising lasted, they caused the death of nine people, among them the military governor general of Huesca. Forces loyal to the Government defeated them, as well as the rebels in Madrid. Two captains who took up arms in Jaca were condemned to death and shot.

After the proclamation of the Republic in April 1931, violent episodes followed, carried out by various political and union forces, repressed by the forces of Public Order and, in certain cases, by the Army (the State of War was declared by successive governments on more than a dozen occasions). There are no definitive statistics on the casualties and damage caused, largely because of the press censorship that was in force during most of the Republican period—but the most complete estimates calculate between 2,629 and 3,628 deaths, from April 1931 to July 1936.

Historian Eduardo Gonzalez Calleja has added 196 fatalities between April and December 1931; 190 in 1932; 311 in 1933; 1,457 in 1934; 47 in 1935, and 428 in 1936, up to July 17. Exhaustive research carried out by Juan Blázquez Miguel estimates 288 for the same period of 1931; 276 in 1932; 536 in 1933; 1,879 in 1934; 142 in 1935, and 502 in 1936, up to mid-July. Blázquez Miguel also points out that during the Republican period, violence caused 12,520 injuries, 13,494 strikes were called, 735 religious buildings were set on fire, 780 assaults and profanations were carried out, as well as 3,866 attacks with explosives or of other nature.

Most of the violence originated in trade unions and left-wing parties: the General Union of Workers (socialist), the National Confederation of Workers (anarchist), the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party, the Communist Party of Spain, Esquerra Republicana de Cataluña and the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification (POUM). From 1934 onwards, the attacks were joined by Falange Española, a local version of Italian fascism, which was very active in 1936.

Deadly clashes took place even between elements of different leftist formations, with a total of sixty-one dead, mainly on the part of socialists and anarchists, while there was not a single fatality among right-wing forces, according to González Calleja’s data.

The parties of the center, the right and the Republican left, which together accounted for the vast majority of the popular vote, were oblivious to the violence, although at times they did not fight it with sufficient firmness. Above all, the left-wing Republicans (Izquierda Republicana and Acción Republicana) agreed in January 1936 on a Popular Front candidacy with the forces that had taken up arms against the center-right government in October 1934: UGT, PSOE, PCE and ERC. After their relative electoral victory in February, IR, UR and ERC came to power, although they were at the mercy of the Socialists and Communists for a parliamentary majority. The main socialist leader, Francisco Largo Caballero, repeatedly expressed his aim to merge with the Communist Party, a project that began to materialize in April 1936, with the youth of both formations. Largo was hailed by his own people, since 1933, as the “Spanish Lenin.”

Differences Between the Two Repressions

At the beginning of the war, the institutions and norms that made up the Rule of Law collapsed. The rebels imposed the State of War and the Popular Front Government handed over the weapons, and with them the effective power, to militiamen from trade unions and left-wing parties.

On both sides the authorities who were not sympathetic were dismissed, from town councilors to Supreme Court magistrates. On the rebel side, many civilian posts were filled by the military. On the governmental side, local authorities and company managements were replaced by revolutionary committees, made up of trade unions and left-wing parties. Civil servants were purged everywhere, for no other reason than their political affinity. For the same reason, numerous dismissals took place in the businesses themselves, both of managers and of ordinary employees.

In both areas there was a general persecution of those who were considered adversaries, even if they had not carried out any hostile action. This was the case from large cities to small towns. There were tens of thousands of murders, along with clandestine burials, arrests, prison sentences, forced labor, seizures, looting, extortion, fines, robberies and threats. In the Republican zone there were numerous cases of people being burned alive, tortured, women raped and corpses desecrated. Five years before the Nazi extermination camps began to operate, Catalan anarchists incinerated their victims in industrial ovens. Other corpses were thrown into raging rivers, chasms or deep mineshafts. With few exceptions, these crimes went unpunished, on either side, by the express will of the respective authorities.

The victims of the repression in the government/Republican zone were mostly murdered, by decision of the Revolutionary Committees. In the rebel zone, most of the victims were executed after being condemned in War Councils, without sufficient guarantees or legitimacy; the same happened in the other zone with the so-called People’s Courts and the Court of High Treason and Espionage.

As for the victims, in what ended up being the “national zone,” almost all those murdered or executed belonged to revolutionary organizations, which rejected democracy. This, of course, did not justify their death, but they were co-religionists of those who in the Republican zone carried out tens of thousands of murders. On the contrary, the great majority of those killed or executed in the zone controlled by the Popular Front did not belong to any violent organization. They were religious, lay Catholics and affiliates or sympathizers of center and right-wing parties.

The repression carried out after the Spanish Civil War by the victors was exercised by military jurisdiction. In general, those who were executed were material perpetrators or those directly responsible for acts of bloodshed. If they had not committed crimes of this nature, those sentenced to death were commuted, whether they were civilian authorities, Popular Army commanders, political commissars, members of revolutionary committees, volunteers of the International Brigades, spies, deserters or even guerrillas who had acted in the national zone, and even if they had had mortal encounters. War actions were not considered blood crimes.

Franco’s Pardons

The norm that regulated the cases in which a condemned person could benefit from a pardon was an Order of the Presidency of the Government—that is, of General Franco himself—dated January 25, 1940. The same regulation ordered the establishment of provincial Sentence Review Commissions, which reviewed ex officio all the sentences handed down by War Councils from July 1936 onwards, always in favor of the condemned. Generally speaking, and at various stages, sentences of six years were reduced to one year and those of thirty years to six. By 1944, 70,858 commutation files had been reviewed.

Also in 1940, in the month of April, parole was granted to inmates over sixty years of age who had served a quarter of their sentence. The Law of June 28, 1940, Supplementary to the Statute of State Pensioners, granted a pension to “the wives, children and widowed mothers of civilian and military employees who, in compliance with sentences imposed by the Courts, are suffering or will suffer the penalty of deprivation of liberty for a period of more than one year.” This norm protected the families of those who had been condemned by War Councils in the national zone, including those who had been shot. Family members were entitled to a pension from the moment of conviction, which in certain cases meant arrears of several years. The widow of General Manuel Romerales Quintero, who in July 1936 was Commander General of the Eastern Circumscription of the Protectorate of Morocco, and who at the end of August was condemned to death and shot, received the pension and arrears in 1941.

Beginning with the regular operation of the Ministry of the Army, in the second half of 1939, all death penalty sentences were examined by the auditors of the Legal Corps, in the Advisory and Justice section of the Ministry. The sentences were studied one-by-one, together with complementary information and petitions for pardon. The latter were not only submitted by the convicted person and his relatives. In many cases, authorities from various fields, especially mayors, local Falange chiefs and municipal judges, signed joint petitions for pardon, often supported by dozens or even hundreds of neighbors. This was also done by a large number of religious, from bishops to cloistered nuns, as well as by victims claiming Christian pardon, among them many widows. The women of the Primo de Rivera family, headed by Pilar, National Delegate of the Women’s Section of the Falange, certified in April 1940 before a notary public the impeccable conduct of Adolfo Crespo Orrios, who was in charge of the Alicante prison when on November 20, 1936, her brother José Antonio, founder of the Spanish Falange, was shot there. One of the signatories, Carmen Urquijo, was the widow of Fernando Primo de Rivera, brother of José Antonio, murdered in the Modelo prison in Madrid in August 1936. The women’s action was successful and the condemned to death was pardoned.

The procedure usually lasted months and the auditors recommended the commutation of more than one third of the capital sentences, by means of reasoned and signed reports. Thousands of sentences were disqualified due to insufficient evidence or new information.

The proposals of the auditors were accepted, in 99.8 percent of the convictions, by the Head of State. Franco only intervened in a handful of cases, mostly in favor of the condemned, and in particular of commanders of the Popular Army, both professional and militia. It was also his personal decision to pardon the Socialist deputy, Francisco de Toro Cuevas, elected in 1936 for the province of Granada, who during the civil war had been political commissar of the Parque de Intendencia in Madrid, where workers who were not sympathetic to the Popular Front were dismissed. The auditors even paralyzed execution orders if they had new information favorable to the condemned. In all these cases, Franco rectified the “decision” that he had previously given.

How many were executed after 1939? According to the internal statistics of the Legal Audit of the Ministry of the Army, up to June 30, 1960, there were 24,949 condemned to death, of which 12,851 were commuted, which means about 12,000 executions. From this figure it is necessary to subtract those condemned for common crimes and to add several thousand executions which took place in the spring and summer of 1939, before the regular functioning of the Army Ministry. An approximate figure of the executed is, according to the author’s estimate, around 14,000. This includes those belonging to the “maquis,” a rural guerrilla group made up of former combatants of the Popular Army, who in the second half of the 1940s carried out attacks in which a thousand people lost their lives.

In view of these numbers, it is untenable to claim that in the post-civil-war period the regime of the winning side in the civil war subjected the defeated to a punishment of a cruelty and viciousness similar, in Europe, only to those carried out by the German National Socialist and Communist regimes.

Those commuted from capital punishment were sentenced to the next lower penalty, i.e., life imprisonment, which was equivalent to thirty years. In practice, they remained in prison from three to seven years. The socialist Francisco de Toro, for example, had his death sentence commuted to thirty years’ imprisonment, then reduced to twenty years, and was released on parole in January 1944, less than five years after the end of the war. One of those who was imprisoned the longest was Cipriano Rivas Cherif, brother-in-law of President Manuel Azaña, sentenced to death in October 1940 and released in 1947.

The proportion of those commuted increased significantly over time. In 1939 only a quarter of the condemned benefited from pardon; but from 1941 onwards it was already the majority. In principle, those sentenced to death could not benefit from the review of sentences, but this criterion was changed in their favor in September 1942.

Pardons of Death Sentences and Reduction of Sentences

During the civil war, both sides had used prisoners, both political and war prisoners, for various duties: fortifications, agricultural work, mines, repairs of damage caused by bombing, etc. The concentration camps had been created in December 1936 by a decree of the Minister of Justice of the Republican Government, the anarchist Juan García Oliver. In the post-civil-war period, the camps of Republican origin continued to operate, such as the Albatera camp in Alicante, and many prisoners were placed in labor battalions, militarized penitentiary colonies, penal detachments, various workshops and reconstruction tasks, in what were called Devastated Regions.

In May 1937, a circular on “paid work for prisoners of war and prisoners for common crimes” was approved; but the most important regulation was the Decree on the Redemption of Sentences through Work of October 7, 1938, which allowed most of the prisoners to reduce the length of their sentences, as well as to obtain a salary for the benefit of their families. The 1939 Law for the creation of the Military Penitentiary Colonies guaranteed that they would have “decent clothing,” as well as medical and pharmaceutical assistance. The following year, an order of December 30, 1940, declared applicable to inmate workers the same benefits that the legislation provided for free workers, in terms of coverage for work accidents, family allowance and legal rest.

At the end of 1939, there were 270,719 prisoners, a figure eight times the 34,526 existing in February 1936 and more than thirteen times the average number of prisoners before the rebellion of October 1934, which was about 20,000.

Beginning in 1940, a policy was initiated, aimed at the gradual release of those convicted of war-related crimes. In practice, the only sentences served were the death sentences that had been ratified. In 1940, parole was granted to those who had been sentenced to less than six years and one day. Nevertheless, at the end of the year, there were still 233,373 prisoners in the prisons.

The attenuation of repression intensified in the following years, largely because the most serious proceedings had already been resolved. In 1941, those sentenced to sentences not exceeding twelve years benefited from parole; and by December 31, the number of prisoners had been reduced to 159,392. The latter figure was reduced to 124,423 at the end of 1942 and to 74,095 at the end of 1943. In this year parole was granted to those condemned to sentences of up to twenty years and one day by a decree of December 17, signed by Franco, which reduced the prison population by more than a third: in April there were still 114,958 prisoners, 22,481 for common crimes and 92,477 “prisoners as a consequence of the revolution,” according to the data of the General Directorate of Prisons.

On December 31, 1944, the number of prisoners was 54,072. And in 1945, a new decree of the Ministry of Justice, dated October 9, also signed by the Generalissimo, provided for the “total pardon” of all those condemned for military rebellion and other crimes up to April 1, 1939, as long as they had not committed “acts repulsive to any honest conscience,” thus reducing the number of prisoners to 43,812. In June of the same year, the number of prisoners was 51,300: 18,033 common and 33,267 political.

A report of the Army Ministry’s Legal Department, dated June 9, 1945, described the situation at that time: “All those sentenced to sentences of up to twenty years are at liberty… Of those sentenced to sentences of between twenty years and one day and thirty years of imprisonment, those included in the benefits of the decree of December 17, 1943 are also at liberty, that is, those who, because of their behavior in prison, advanced age, state of health or other circumstances, have earned it.”

The overall balance, therefore, is that those sentenced to imprisonment did not even serve half of the custodial sentence. On average, only a quarter, and as time went on, even less. This is shown by the study of individual cases.

One example is General Luis Castelló, who was Minister of War between July and August 1936, who fled to France and was handed over to Spain by the German occupiers. In 1943, a War Council condemned him to death, a sentence commuted to life imprisonment (thirty years); but the time he spent in military prisons was three years and nine months. Antonio Lafuente Estefanía, who would become famous as an author of Western novels under the name of Marcial, during the civil war had been councilman of Chamartín de la Rosa (Madrid) for the anarchist union CNT, a position in which he protected persecuted right-wingers. He was also a volunteer soldier in the Popular Army. Tried by a War Council in July 1941, the prosecutor requested the death penalty, but he was sentenced to twenty years and three months; later the sentence was reduced to twelve. In November, when he had served two and a half years in prison, he was granted mitigated imprisonment at his home.

After a new pardon decree of December 27, 1946, the number of prisoners was 36,370, similar to the number in February 1936.

Return of Exiles

By that time, the question had been raised as to what should be the rule applicable to those who had been exiled at the end of the civil war and wished to return to Spain. The Ministry of Justice introduced a decree, dated February 4, 1947, “by which rules are given to legalize the situation of Spanish exiles abroad and facilitate their return to Spain.” It established that “the interested party will be informed if the facts do not constitute a crime, are crimes included in the pardon or are not included.”

The Ministry of the Army, for its part, issued some “Instructions or rules to which the judicial authorities must adjust their actions in relation to those who had the status of professional military personnel and wished to return to Spain… Provided, it specified, that they had not had a very outstanding performance in the war of liberation.”

The application of these instructions was as follows: once back in Spain, the exiled republican soldier had to present himself before the military court that had corresponded with him, with his travel on national territory paid for by the Ministry. The Court would inform him of the possible responsibilities, “so that with knowledge of them, those who so wished, could return abroad.”

During the 1950s, very prominent commanders of the People’s Army of the Republic returned to Spain, including Vicente Rojo, who had been General Chief of the Central General Staff between 1937 and 1939, and who was court-martialed and immediately pardoned. Another prominent commander who returned, although only temporarily, was the former communist Manuel Tagüeña, chief of the XV Army Corps in the Battle of the Ebro, who was able to visit his sick mother.

The return to Spain of the exiles became widespread, in fact, during the 1950s. In the interview he gave to the French newspaper Le Figaro (June 13, 1958), Franco himself described the situation in these terms: “A small number of them have committed general civil law crimes during the civil war. Lastly, numerous are those who come to our consulates to request authorization to return to their homeland, either temporarily or definitively. In 99.9 percent of the cases, such authorization is granted. Spain is open to all its citizens, without distinction, except for criminals.”

During the thirty years following World War II, there was a general downward trend in repression, only altered in the second half of the 1940s by the actions of the “maquis” and from 1968 by the terrorist group ETA and other smaller groups. The last person to be shot for acts committed during the civil war was, the communist leader Julián Grimau, in April 1963, who had been chief of police in Barcelona. During the Franco regime, the historical minimum of prisoners, for all crimes, was 10,622 in 1965, thanks to the successive application of two general pardons, one in 1964 for the 25 years of Peace (counted from the end of the war) and another in 1965 for the Compostela Holy Year.

On April 1, 1969, in application of the Penal Code and thirty years after the end of the civil war, all crimes committed during the conflict were declared time-barred (subject to a statutes of limitation). For this reason, when Santiago Carrillo, secretary general of the Communist Party, returned to Spain in 1976 and was arrested, no proceedings could be brought against him for his responsibility in the massacre of Paracuellos de Jarama (Madrid), where several thousand people were murdered in November 1936.

The most extraordinary case linked to the post-civil war repression occurred when the grandson of a man condemned to death married a granddaughter of Franco. The condemned man had been the Engineer, Colonel Tomás Ardid Rey, who throughout the war served in the Popular Army, where he became General Commander of Engineers of the Army of the Center and later General Inspector of Engineers. Sentenced to death in January 1940 by a general court martial, Franco commuted the death sentence on February 12. The sentence was replaced by life imprisonment, equivalent to thirty years, but he was paroled in 1943, after his sentence was reduced on May 18 of that year to twenty years and one day. On March 7, 1946 he was pardoned.

Almost thirty years later, on March 14, 1974, when Colonel Ardid Rey had already died, his grandson, the architect Rafael Ardid, Villoslada married Francisco Franco’s second granddaughter, María de la O—Mariola—Martínez-Bordiú Franco, whom he had met at the University.

The ceremony was held in the chapel of the Palace of El Pardo, residence of the Head of State. Franco sponsored his granddaughter, while the groom was sponsored by his mother, Pilar Villoslada. Among those in attendance were the Princes of Spain, Juan Carlos and Sofia, Carmen Polo de Franco, the Duke and Duchess of Cadiz (Alfonso de Borbon had married Franco’s eldest granddaughter, Carmen, two years earlier) and the entire government. One of those who signed as a witness, on behalf of the groom, was the President of the Government, Carlos Arias Navarro.

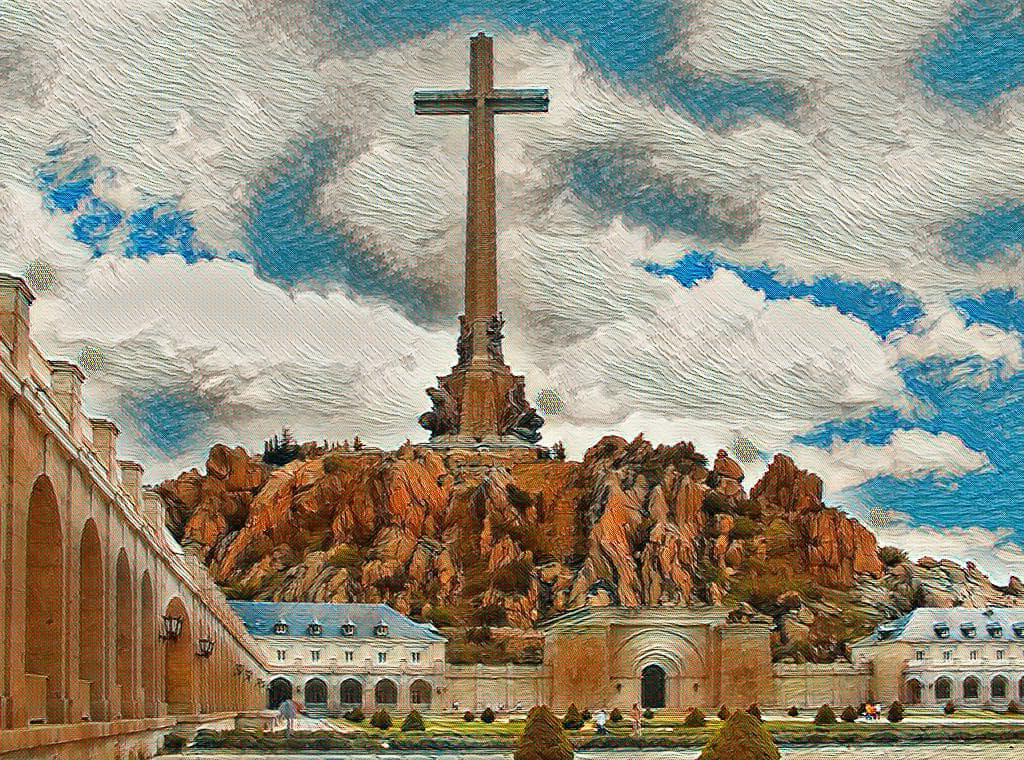

Almost half a century later, Rafael Ardid and Mariola have created a family and are still together. Their life has been presided over by discretion and is the only marriage of Franco’s seven grandchildren that has endured. On October 24, 2019, two of their children, great-grandchildren of Tomás Ardid Rey and of the former Head of State, carried on their shoulders the coffin containing the remains of Francisco Franco, when these were exhumed from the Valley of the Fallen.

Much earlier, after the proclamation as king of Juan Carlos I, in November 1975, all death sentences handed down by the courts were commuted and capital punishment was abolished—except for military jurisdiction in time of war—by the 1978 Constitution, earlier than in the French Republic.

Miguel Platón is well-known Spanish writer and researcher, who has written several important books on contemporary history. This article appears through the kind courtesy of La Gaceta de la Iberosfera. This article appears through the kind courtesy of La gaceta de la Iberosfera.