Can language express truth? Can language give us a clear picture of reality?

Discussing Postmodernism has become almost prosaic given the intellectual climate of the 2010s. However, it has posed questions which directly challenge the most classical assertions of how we understand the world around us. For that alone it is worth responding to.

Postmodernism also remains relevant because much of current thinking is rooted in Postmodern ideas. This goes beyond just academic circles: it is easy to catch Postmodern ideas in everyday discourse. Nothing is unusual about hearing someone retort in an argument “Well, that’s subjective,” or if they are more well versed and a little bolder “That’s just interpretation, there’s never really any one meaning.”

These ideas originate from Postmodern language theory in particular. What is referred to as “Postmodernism” refers to a specific idea of language and how it functions. These ideas were shaped by numerous thinkers in the 1960s and 1970s: most popularly through French thinkers like Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida, who took the core ideas on language and related them to concepts of power, oppression, and freedom.

A critique of language of all things may appear benign and simply technical at first, but the challenge undermines confidence in our ability to have knowledge and the possibility of truth. Let us explore both, but first I will need to explain the Postmodern understanding of language which I have been alluding to. I do warn that in discussing “Postmodernism” that there is a risk in generalization. The term remains elusive and the various thinkers who are characterized as Postmodern are not totally unified in their views. I will stick to explaining the broadly agreed upon problems Postmodern thinkers find in language and dabble with some responses.

Postmodern theories of language challenge the belief that language provides a stable way of understanding the world. When you use language, you are partaking in the act of representing things in the world through concepts. This does not have to be simply through speech, when you are thinking or simply identifying an object you are representing the world through language. If you are for instance looking at a red apple, you will have the corresponding thought “That is a red apple,” which frames the experience and allows you to understand it. In that case, language is being used to formulate a claim which represents something out there in the world, namely that the apple is there and that it has the characteristic of “redness”. “There” is used to represent a concept of space–namely where the object is–and “red” is used to represent a concept of colour. Real things are therefore represented with concepts in language.

Postmodern language theories argue that this sort of linear connection between language and objects in the world is fallacious and that, in fact, these kinds of representations are unstable. Instead of language being an accurate link to understanding reality, it is a product of culture and social circumstances. Therefore, representations and language are more indicative of culture rather than an objective reality.

The argument is that all human thought is done through language and that language has an intrinsic “messiness” to it. It relies on words and signs which Postmodernists claim can have countless meanings and interpretation. Without unified meanings Postmodernists argue that it becomes impossible to have singular representations of things in the world, meaning there is a large degree of interpretation to what is deemed reality–therefore, reality is never separated from a subject.

Language having a cultural dimension also poses a challenge. Since, in this view, meaning is framed by the culture which creates it, what language can express about reality is structured by the types of discourses and meaning which is possible with the ideas of that culture. What Postmodernists are arguing is that the ideas of a culture limit what language can say about reality.

If true, this has significant implications, because every human body of knowledge (“epistemology”) has relied on the intuition that language can at least roughly represent reality. Without that foundational assumption, it is impossible to make any claims about the world or have any form of understanding–consequently defeating the possibility of having knowledge entirely.

To the Postmodernist, classical accounts of truth–like that of Plato’s–which use language via propositional logic, or other bodies of knowledge which rely on the experiential, reason, or narrative cannot tell us anything about the world, due to their use of language. The strong Postmodernist must therefore reject science, history, and philosophy, as they attempt to rationalize the world using language.

This is synonymous with the Postmodern rejection of “totalizing” narratives, also abbreviated as meta-narratives. We will return to this, as it is linked with Postmodern views of freedom and what is dubbed the “domination of language.”

If language cannot tell us anything about reality, then how can we understand the world?

The answer is that social construction is the prime shaper of reality. This means that, in a Postmodern paradigm, it is impossible to separate reality from the experience of a subject rooted in social-cultural circumstances. Instead, reality is something which is interpreted and must be represented, so it cannot possibly be understood objectively. The world is therefore quite literally constructed out of how it is represented by a culture throughlanguage. Language and culture are seen to shape our notion of reality to such a degree that it is impossible to understand reality outside of them.

This is why history is deemed an impossible pursuit in a Postmodern context. The argument is that the cultures and, therefore, the languages of the past and present are so different that they become alien to each other. The modern historian is detached from the framework with which people of the past understood the world–i.e.: their meanings and language. Because of this, it becomes impossible for a modern historian to truly understand the past.

Ideas such as truth, value, and justice are also seen as meanings which are constructed through language and projected onto reality. In a Postmodern context, this means that these ideas must be seen as derived from human beings–not the world nor nature.

What this all alludes to is the fact that subjectivity becomes important if language, ideas, and knowledge are not rooted in reality, but instead construct it. Subjects and the culture which frames their thinking create particular discourses, which in turn contextualizes how people understand reality. Reality, when paired with the belief that people are always determined by their culture, becomes rather atomistic, since there are series of interpretations of what reality is, but no singular, true “objective” reality.

Taking this position entails that cultures and subjects are insular from the world or that their representations are not shaped by things in the world which they are referring to. This seems rather unintuitive because when people use language they do seem to be referencing things in the world around them.

This account of language also does not take into account that some concepts are much more stable than others, and that such concepts limit the possibility of mixed meanings and interpretation. For example, if you take the concept of “tree” to signify tall wooded objects, that meaning is relatively stable across the languages of different cultures and time periods. You could take the French word for tree “arbre” and the old English world for tree “Treo” and they would signify the same concept–a tall wooded object. Though, it should be acknowledged that interpretive differences can arise if the trees have different symbolic or metaphorical meanings across the different cultures.

Accordingly, another important concept of Postmodern thought comes from the Discourse theory of the Poststructuralists. Discourse theory states that the signs and symbols which language uses to represent the world fundamentally alters the psyche of people using language. This shapes their very ability to perceive the world around them. Postmodern discussions of politics tend to revolve around this idea of language.

Power, therefore, becomes closely linked with language in Postmodern thought as a consequence of language’s ability to shape psyche. Thinkers like Foucault focus especially on power because they view language as a subtle, insidious form of power. It is seen as something which dominates people not through coercion or force of arms, but by shaping how they are even allowed to understand the world. In the view of Foucault and many Postmodern thinkers, power is not necessarily held by the rich elite or politician, but instead those that shape the discourses and ideas which everyone–from the rich elite, to the politician, to the layman–use to understand the world. Because of this, strong Postmodernists have a certain skepticism of bodies of knowledge like history, science, and religion or what they call “metanarratives,” since they are viewed as means of dominating our conceptions of the world.

Foucault in his discussion of power talks about how language is selective. Here he takes inspiration from French poet Raymond Roussel who expresses the idea that language does not designate a word for every concept for which designation is possible. This implies that there is a poverty to language since it cannot express all that can be expressed. This is a recurring objection in philosophy preceding the Postmodernists; Ludwig Wittgenstein famously makes a similar critique of language amongst others.

Where the Postmodern critique differs (though much of it is inspired by Wittgenstein) is the implication brought about when this idea is tied to power. Foucault posits that because language only selects certain parts of reality, it only provides a partial glimpse of reality. Those selections, to Foucault in particular, are tools of domination and power: reality is shaped in accordance with what those who have power want to be believed. Language is therefore restrictive in how it shapes reality and the fact that it only allows certain discourses, in accordance with those in power.

Before I delve into a criticism, I would once more like to clarify that “those who have power” in this view is not discussing shadowy bureaucrats or a secret cabal of world leaders planning every event throughout world history. Instead, it is framed as those who have traditionally shaped ideas and discourses in Western thought. Foucault is referencing everything from the classics, the enlightenment thinkers, and science when he talks about “power.”

That being said, questions should certainly be raised when Foucault argues that these thinkers have exercised a sort of domination over people and their discourse. It underestimates the capacity for people to challenge these frameworks of thought, and assumes a certain tyrannical agenda amongst these thinkers to shape reality.

Freedom then becomes a prime goal for Postmodern philosophy. Understanding how to achieve it is a contentious point for Postmodern thought. Derrida’s understanding may be the most popular, which is that representation and language are inescapable–therefore making the achievement of freedom impossible. Most Postmodern thought stems from this initial position of Derrida’s, so the question then becomes: “If one cannot be free from the domination of language, how does one best find freedom?” The end is that each individual must find a relative truth for themselves; that is the best one can do to prevent themselves from being dominated through language and oppressive discourses.

There is a problem with this Postmodern emphasis on Freedom, that makes it impossible to function within a Postmodern framework. To make this point more poignant, I will use a Postmodern argument to refute it.

Let us start with Derrida’s idea of dichotomies. Derrida argues language in the West is flawed because it is limited to various dichotomies: Good vs Evil, Presence vs Absence, Male vs Female, Speech vs Writing. Discourse tends to privilege one part of the dichotomy over the other: Good rather than Evil, Presence rather than Absence, Male rather than Female, and Speech over Writing. The argument is that the choice of what to privilege has no basis in objectivity or goodness, and that in reality neither choice within these dichotomies is inherently better than the other.

In a Postmodern framework, this has to be the case because if language does not refer to anything than truth does not exist. This introduces the problem that all discourses must become equal, meaning that you must believe that all ideas are equally privileged or equally worthless–a truly daunting proposition. The majority of Postmodernists choose to believe in the former: that all meanings, even within dichotomies should be treated as equal.

Then the question becomes how can the Postmodernist value Freedom over Oppression? How do they discern that Freedom is indeed privileged to oppression? Why are Postmodern thinkers also quick to value the individual over the collective? Even while disparaging the ideas of the Enlightenment and the West, Postmodern thought seems rather happy to take some of it as baseline assumption.

If the Postmodernist seeks to answer these questions, they will fall guilty to using value judgments rooted in language or needing to accept metanarrative.

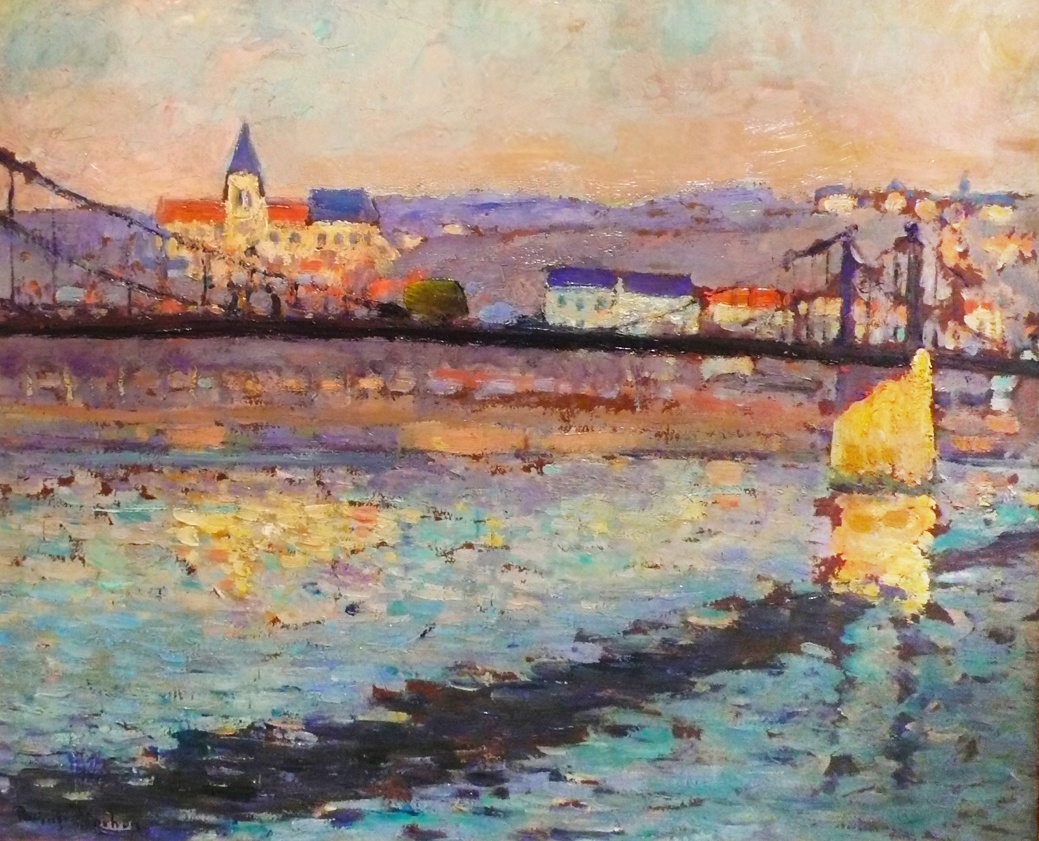

The photo shows, ” Triel sur Seine, le pont du chemin de fer,” by Robert Antoine Pinchon, painted in 1904.