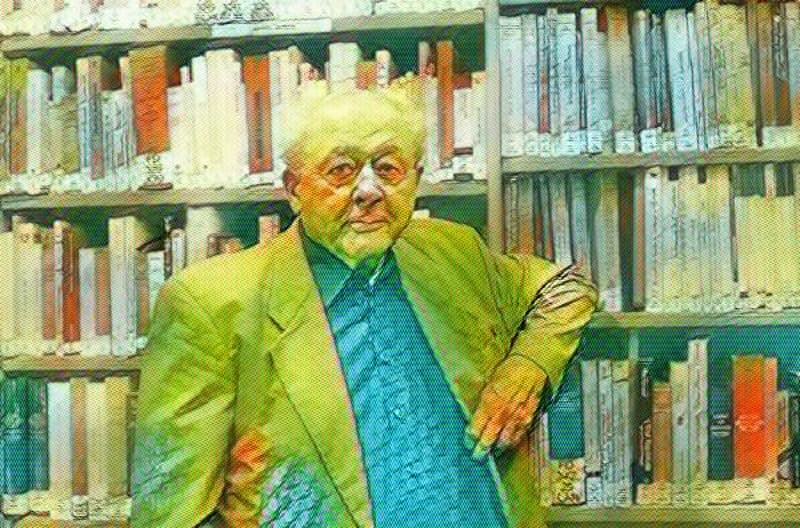

Pierre Legendre (1930-2023) was one of the greatest thinkers that France has produced in modern times. His rich and nuanced thought, which encompassed history, philosophy, film, psychoanalysis, anthropology, and the law, he himself characterized as “dogmatic anthropology.” His passing on March 2, 2023 marked the end of an era in that he was the last “Renaissance man,” one learned in so many fields of knowledge, least of which was his mastery of a beautiful Latin style.

The French philosophy, Pierre Musso, author of Introductions à l’œuvre de Pierre Legendre [Introduction to the Work of Pierre Legendre], published just a few days before the thinker’s death, assesses and comments on the monumental legacy that Legendre has left behind. Professor Musso is in conversation with PHILITT, through whose kind courtesy we bring you this interview.

PHILITT (PL): The silence that followed the death of Pierre Legendre outraged some of his readers. Do you share this indignation? How do you explain the relative indifference of the academic world towards his thought and his work?

Pierre Musso (PM): I am not overly disturbed by the low media profile of Pierre Legendre’s death. Legendre himself did not particularly like the media or academic circles, and avoided them as much as possible. When one sees the tributes that the media pay, especially in the audiovisual sector, to various popular personalities—which Legendre was not—one can legitimately think that it is rather to Legendre’s glory that he was not celebrated in this way. Moreover, Legendre has always been a contrarian, on the fringes of academic and, of course, media institutions.

The real cause of this post-mortem silence, in my opinion, lies in the sheer ignorance of Legendre’s work in these circles, and in particular in France. If his work remains important and widely disseminated, notably his first film, La fabrique de l’homme occidental [The Fashioning of Western Man] (1996), with the text published in the collection of the Mille et une nuits [Thousand and One Nights], it is especially known and recognized abroad. There are already translations in German, in part in Italian, in Japanese, and some in English.

Paradoxically, many thinkers have been inspired by Legendre, often without quoting him. Legendre has been, as he himself said, “plundered” a lot, for a long time, including by intellectual luminaries who do not necessarily refer to Legendre’s work when quoting him. This is the fate of important works. His work spanned some sixty years, from the 1960s to the present. He pursued his work with constancy and on the fringes of institutions and disciplines. And this work is immense. Immense not only by its volume—some forty works, including his ten “Leçons [Lessons],” which contain the essence of his thought—but above all by its originality and complexity. I prefer to call it a cathedral work. In other words, a monument with an architecture of great complexity, but which offers several entrances and where one is free to go and admire this stained-glass window, that work of art in one corner, that text in another.

One of the aspects that explains the difficulty of apprehending Legendre’s thought is that he cannot be put away in a compartment, educed to a discipline. Legendre was not simply a jurist, a psychoanalyst, perhaps a philosopher and probably more an anthropologist. He himself would have gladly called himself “founder of dogmatic anthropology,” which is obviously incomprehensible, even dangerous, for most media.

PL: As you write in the introduction to Introductions à l’œuvre de Pierre Legendre [Introductions to the work of Pierre Legendre], “a scholar at the interface between science and poetry,” Legendre stands out from recent thinkers because of his erudite style and his multidisciplinary analysis that spans two millennia of the history of thought. In your opinion, what is Pierre Legendre’s genius—in the sense of the Latin ingenium?

PM: Legendre’s fundamental intuition is that of symbolic determinism. What is it about? Legendre places at the heart of his thought the question of why? This question was formulated, to put it simply, by a Father of the Church, Isidore of Seville, an encyclopedist of the 6th-7th century, who asked both why live and die? And how to live and die? The question of why is that of meaning; and, beyond meaning, that of the symbolic, knowing that the “speaking animal,” as Legendre calls it, constantly asks itself the question of why, and is aware of this constitutive intrigue of its being, transmitted from generation to generation. The stake, to “institute the human animal,” is to build founding narratives, myths or fictions, which answer this question of the why?

Nowadays, in Western society, the question of why is largely evacuated. Either it takes refuge in traditional religions, or society only responds to the question of how, to the question of norms and technique. We are thus faced with what Legendre calls a “wandering of the symbolic” or a “symbolic disintegration;” that is, a phenomenon of de-symbolization. This means for Legendre that there are several forms of “rationality.” That of the principle of non-contradiction, first of all, the rationality of logic in the Aristotelian sense and a fortiori in the Hegelian sense; that is to say, the constant rise in abstraction in rationality. Legendre borrows from Husserl the term of “surrationality” to characterize the West of today, where Bachelard spoke of “surrationalism,” in reference to surrealism.

The second form of rationality, fundamental, is that of the dream or the myth, where the principle of non-contradiction does not function anymore. This is the beauty of dreams, which explains why we spend half our lives dreaming, whether asleep or awake. This second rationality, just as important as the first one, is occupied by beliefs, myths, religions. This word “religion” did not please Legendre very much. In his last works, in the last ten years, since Lessons IX, he preferred the notion of “fiduciary,” borrowed from Paul Valéry. This term introduces the notion of fides, faith, which structures a civilization from its founding myth, which belongs to the symbolic, a term that could also be discussed at length.

The third form of rationality, which has often been buried in the West but which is very prevalent in many societies, concerns the corporeal. This last one gave place to Pierre Legendre’s works on the dance, La passion d’être un autre [The Passion to be Another (1978)]. If one does not have in mind these various forms of rationality of the speaking animal, one locks oneself, as the West does today at the time of the Techno-Science-Economy, only in the surrationalism or the technical, economic and techno-scientific hyperrationality.

In this respect, the accusation of conservatism made against Legendre does not stand up to analysis. Indeed, symbolic determinism is a reaction to what other currents, for example Marxists, have called “economic determinism” or still others “technical determinism.” Basically, as I write in a provocative way in these Introductions, one could link Legendre to a whole neo-Marxist or neo-Marxian current, a current which, against this formula of economic or technical determinism prevalent in Marx, Engels or Lenin, has valorized, within the Marxian matrix, the question of cultures, of the symbolic and of the imaginary. I am thinking in particular of Gramsci, Cultural Studies, the Frankfurt School (Adorno, Horkheimer). From this point of view, we can make a connection, which I myself sketched out in La Religion industrielle, between Legendre’s contribution and these currents. In any case, to classify Legendre among the conservatives is of little interest.

PL: At what moment and in which work do you situate the birth of “dogmatic anthropology” and the Legendrean project of subjecting the West to a kind of great genealogy or psychoanalysis?

PM: To understand Pierre Legendre’s project, one must first understand the meaning he gives to dogmatic anthropology. Legendre deliberately borrows a word, that of “dogma,” which he describes as “dangerous, sulfurous,” since “dogmatic” is often used to characterize fixed thought. Legendre in fact reinvests the Greek etymology of “dogma” (δόγμα), that is, that which appears and which, in its appearance, is a feint. It is thus a staging, a dramatization of the symbolic which, etymologically too, is the link that separates, according to the image of the dollar bill torn in Western filmss to find itself at the end of a contract. This link that separates refers to the unspeakable and the invisible: God, the Fatherland—one thinks of Kantorowicz’s text on the formula “to die for the Fatherland”—the Republic, Peace, and other beliefs or founding myths of our societies. For example, it seems to me that one of the major myths in the West today is that of scientific progress, established as a myth by positivism in particular. The institutions, their norms and their laws, in a society, are established and founded “in the name” of a symbolic myth, of a founding fiction. Pierre Legendre often quoted in his work this formula from the Middle Ages: Fictio figura veritatis est, i.e., “fiction is the figure of truth.” This aspect is fundamental to Legendre.

The nodal moment in Legendre’s work seems to me to be his thesis, supervised by Gabriel Le Bras and defended in 1957, entitled, “La pénétration du droit romain dans le droit canonique classique : recherche sur le mandat (1140-1254)” [“The Penetration of Roman Law into Classical Canon Law: Research on the Mandate (1140-1254”)]. Legendre was later greatly influenced by historians such as Ernst Kantorowicz or Harold Berman, who showed how the West was built, starting with what Berman called the “Big Bang of Western thought,” namely, the “papal revolution,” i.e., the Gregorian reform. For Legendre, as for Kantorowicz, this rupture of the eleventh and seventeenth centuries is the key moment when Roman law, inherited from the Empire which possessed a powerful normativity without answering the question of why, met Christianity; a kind of faith without law. This encounter was essentially born of the compilation made by the medieval jurist Gratian, an author often cited by Legendre as the founder of Western institutions, in the Decretum Gratiani or Concordia discordantium canonum (1140). This Decree, prolonging the “papal revolution,” maintains that man is governed according to two measures, which, on the level of institutions, will result in the opposition and the hierarchy between the papal authority and the power of the emperor, the spiritual foundation and the normative foundation. It is therefore the meeting of two monuments: the legal block inherited from Roman law and the heritage of Christian spirituality.

The intuition of dogmatic anthropology is really explicit in 1974, with the publication of L’amour du censeur : essai sur l’ordre dogmatique [The Love of the Censor: An Essay on the Dogmatic Order]. The notion of “dogmatic” appears clearly for the first time in the title of the work. With Jouir du pouvoir. Traité de la bureaucratie patriote [The Joy of Power. A Treatise on Patriotic Bureaucracy], these are the two founding texts of Legendre who, until 1982-1985, with the publication of Leçons II. L’empire de la vérité : Introduction aux espaces dogmatiques industriels [Lessons II. The Empire of Truth: An Introduction to Industrial Dogmatic Spaces], gave rise to a dogmatic anthropology. He then extended this reading of the Gregorian reform in the following works, sometimes giving the impression of repeating himself, as Lucien Sfez reproached him for doing when he devoted a long chapter to Legendre’s thought in his Critique de la communication [Critique of Communication]. Legendre repeats himself, in my opinion, because he discovered a fiduciary structure, an invariant throughout history, which he finds, with Kantorowicz and Berman, in the Gregorian reform: the double structure of man governed by the rationality of reason or normativity and that of myth. These two forms of rationality mentioned above were assembled during the Gregorian reform and thus constitute an institutional structure of the West.

Here we enter the second period of Legendre’s work. Indeed, Legendre establishes a junction, notably from Lessons II that led to his film Dominium mundi (2007), between the “Gratian moment,” in the twelfth century, the luminous century of the High Middle Ages, and the hyper-technological rationality of the “managerial revolution” of the twentieth century, named as such in James Burnham’s important book, published during the Second World War: The Managerial Revolution: What is Happening in the World (1941). Legendre notes that management has a relationship to the governance of the world that is faithful to Gratian’s decree but obeys a single measure: efficiency. The why is evacuated at the cost of a de-symbolization: what remains is the how, which Legendre calls the “Gospel of Efficiency,” the dogma of effectiveness that results from the industrialization of the West. His strength is thus to have noticed that from the Gregorian reform came two major institutions of the West: the State based on law, which is at the heart of his reflection, and the Enterprise based on management. His criticism of the disintegration of the State, quite rightly, makes him value management as a new form of rationality in the West.

When Legendre, in this period, tried to think the essence of institutions, he also did so from linguistics, taken up by Lacan. What characterizes the human, the speaking animal, is that he divides words and things. He thus enters, by definition, in the representation and to dissociate himself from the narcissistic image, that is to say from the enclosure, as Lacan underlined it; between oneself and his image, man needs a third party, the Big Other in the Lacanian sense. Any society is structured according to a ternary scheme, which Legendre takes from classical anthropology. But if we leave ternarity to enter a binary structure, as is the case in the contemporary West, where the institution dialogues with rationality alone, the balance of society is threatened. Any society is ternary because the human animal distinguishes words and things by the word. The first symbolic institution is therefore language. Following in Lacan’s footsteps and borrowing from Saussure’s linguistics, Legendre erects the bar that separates the signifier from the signified, a first form of institution of the Third. In the mirror stage of Narcissus, there is also a third term between the subject and his image: the mirror.

Finally, a last period of his work stands out after 2009, in the last fifteen years of his life. This moment of his thought is devoted to the question of the religious. Legendre wanted to produce a film on religion, following his three famous documentaries: La fabrique de l’homme occidental [The Fashioning of Western Man], Miroir d’une nation: l’ENA [Mirror of a Nation: Ecole Nationale d’Administration] and Dominium Mundi: l’Empire du Management [Dominium Mundi: The Empire of Management]. Having run out of time, he left us only one work, Les Hauteurs de l’Eden [The Heights of Eden] (2021). In the texts of this period, he shows a preference for the word “fiduciary,” deeming that the word “religion” is worn out. As he often wrote, one does not know a society that does not have a fiduciary architecture, a staging in aesthetics, music, theatrics, etc.; and this, whatever the society and not only in the West.

This interest in the fiduciary leads him to make one last great discovery, in Leçons IX. L’autre Bible de l’Occident : le monument romano-canonique [Lessons IX: The Other Bible of the West: The Roman-Canonical Monument]: the idea of “Schize” [“split”], according to a term borrowed from Lacan. Just as the Gregorian reform provides the link that separates, the foundation of the symbolic, the Schize designates the moment when, while the juridical block, that is to say the structure of rationality and normativity with which the West is endowed—that of management and law today—remains indestructible, the symbolic enters into complete erosion. The West can substitute a myth for the other, pass from God to the Republic, from the Republic to the Nation, to Progress, etc. At the time of the Schize, the link that separates is separated: separation prevails over religion which, etymologically, designates both the reading (religere) and the link (religare). The knot that held the two aspects, distinguishable during the papal revolution, is broken.

PL: Aware of the de-civilization that is taking place, in the light of the Techno-Science-Economy, in the “managerial West,” Legendre seemed, in his last works, to be definitively leaving a ship that is sinking more and more at each “bifurcation,” according to the term you use in Le religion industrielle. How did the author of l’Avant-dernier des jours [The Penultimate of Days] envision the next decades of the West?

PM: In several places in his work, Legendre criticized the Durkheimian approach to religion. According to Legendre, a great rupture took place from the moment when religion became an individual and subjective choice. Hence his preference for the term fiduciary. Originally, religion designates that which founds and governs the whole society which is held together by this foundation: myths, beliefs etc. Legendre criticized, for example, the existence of a free market of religions, the “to each his own belief,” which has as a consequence that the answer to the why is in the individual sphere. This de-symbolization leads, according to him, to a social disintegration, since the foundation of society, which makes it constitute and transmit itself from generation to generation, comes from the collective answer to the why, which constitutes the identity of the West and the genealogy of each society.

From the moment when religion becomes an individual matter, a free market, contemporary beliefs, in the light of the Techno-Science-Economy, come under hyper-rationalism and technical or techno-scientific hyper-rationality. The “In the name of” has moved towards Progress, Performance and Efficiency. Now, the idea of Progress being, for a while, debated and in the process of disintegration, there remains the technocratic and techno-scientific hyper-rationality. The future of the West, according to Legendre, is the capitalism of the New Age, the technolatry of Silicon Valley, transhumanism; that is to say, the myth of immortality, calling into question all the limits that are at the foundation of the symbolic. Everything that is technically and scientifically possible must be realized—such is the great myth of Silicon Valley. We are entering into a pure positivist functionalism, driven by the mythology of techno-scientific progress. In this respect, for Legendre, the West is heading for disaster. A society that frees itself or abandons the symbolic is condemned to social decay. From this point of view, Legendre is rather pessimistic.

Legendre saw what the West does not want to see of itself, according to his formula, and therefore looked at it from the perspective of foreign cultures, especially those of the South: Japan, Asia and especially Africa, which he visited a lot. There are therefore other civilizations that have not abandoned the why, or that have given it a different content: community and territory in the case of Africa, for example. Through positive globalization, the concert of nations, the West brings to light the values of other civilizations called “of the South.” In this respect, if he feared an “end of the West,” like Spengler or an “end of philosophy” in cybernetics like Heidegger, Legendre emphasized that this decline valorizes other forms of civilization and seems to call for another positive globalization in the concert of civilizations.

PL: If he willingly recognized, with Blumenberg, the “legitimacy of modern times,” Legendre exposed, on the other hand, the “medieval crucible” of this same modernity. In the “secularization quarrel,” which goes back at least to Hegel, and in which he takes part in spite of himself, what is Legendre’s position?

PM: One cannot have a society without symbolism, without a foundation of beliefs and myths; this is, as I have already expressed above, the starting point of dogmatic anthropology. This is why, according to Legendre, there is no society that can be secularized. Religions or fiduciary structures remain, even if they become secular with the industrial religion of the “techno-science-economy.” In dogmatic anthropology, it is institutions that hold a society together. Now the institution, Legendre explains, is what makes the collage between the why to live and the how to live; that is to say between the symbolic and the norm. If institutions no longer produce this “glue,” according to a term borrowed from the neo-Platonists, the structure of societies collapses. Legendre often resorts to the architectural metaphor and describes the structure of societies, built like monuments. Hence the importance, for Legendre, of genealogy and the link woven between the “medieval melting pot,” where the foundations of this monument that is the West are laid, and contemporary Management, the current face that this same West gives us to see. Since his vision of history is not linear but sedimentary, what is deepest in history, like the lava at the bottom of a volcano, can become the most burning actuality.

What interested Legendre is the invariant structure of the institutions that make up society. If today the West is faltering, this means that its institutions, starting with the State, still a major institution in the organization of nations in the democratic West, are no longer doing their job of “bonding” faith and law. Thus, the balance of the dogmatic edifice of the West is threatened. This disintegration of the state institution is a distant consequence of the Schize. At the time of the Schize, the State “recovered,” so to speak, the symbolism of the Church by transferring the theological to other Referents. Then, according to the great revolutions of its history, those identified by Harold Berman—the Papal Revolution, the Reformation, the English, French, American and Russian revolutions, as well as the managerial revolution (end of the 19th-20th century)—the West was constituted and the State borrowed different “founding References.” Today, the West speaks in the name of efficiency, borrowing the managerial doctrine, which I call in a book the State-Enterprise.

But this collapse of the edifice goes back further. In the last millennium, the Church was the great founding institution and the State largely took over the Church model. This model of the Church-State became a nation-state from the 16th century, with Machiavelli, etc. It triumphed with the Treaty of Rome. It triumphed with the Treaty of Westphalia (1648) and Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651), the acme of the State model, until the French Revolution and the beginning of the 19th century. Moreover, the State constitutes, especially in France, the pivotal institution, to which Legendre devoted his very first works, in connection with the history of administrative law for example. When Legendre sees the State becoming a “ghost,” as he writes in Fantômes de l’État en France [Phantoms of the State in France], he obviously had in mind the French model, where the State is the institution of reference. The “lassitude of the state” and its disintegration was a major concern of Pierre Legendre. I hypothesize, in several of my books, that business and management could perhaps replace, and are already serving as crutches for, this decaying state.

PL: A scholar perched on the shoulders of other scholars whose heir he readily acknowledged himself, Pierre Legendre was first and foremost a scholarly reader. If one had to make—a legendary exercise par excellence—the genealogy of his thought, with whom would you compare the author of the Leçons [Lessons]?

PM: Beyond the contribution of psychoanalysis, law, history and anthropology, Pierre Legendre was first and foremost, in my opinion, a great scholar, therefore an encyclopedist, a walking library, such as no longer exists. Legendre spent his life not only in conversations with the greatest, but in libraries all over the world, his nose in manuscripts. One can compare him, of course, to historians such as Kantorowicz or anthropologists such as Lévi-Strauss, from whom he certainly drew inspiration when he thought up his dogmatic anthropology, a reference to structural anthropology. Legendre himself cited his exchanges with André Leroi-Gourhan, who studied the relationship of the human to the world, both technical and symbolic. This duality crosses, under different forms, the work of Legendre.

Moreover, we know that he knew Lacan, that he met him frequently, that the latter helped him to publish in his book series. Legendre insisted, moreover, that his work completed a subject that the Paris Freudian school did not want to tackle, namely the institution, a blind spot in Lacan’s approach according to Legendre. However, Legendre descended more immediately from Freud. From the latter, he retained a sentence that is essential to his reasoning, found in Civilization and Its Discontents (or The Discontent in Culture), published in 1935: “If the evolution of civilization presents such similarities with that of the individual, and if both use the same means of action, would we not be authorized to make the following diagnosis: have not most civilizations or cultural epochs—even the whole of humanity perhaps—become “neurotic” under the influence of the efforts of civilization itself?”

Legendre was mostly in the line of great scholars. I am thinking of Athanasius Kircher, the German Jesuit and encyclopedist who, in the 17th century, was more important and better known than Newton. This great scholar in all fields—mathematics, astronomy, medicine, archaeology, etc. – was, for Legendre, a personal friend, whom he met and left every day, in his library. This was not limited to the producers of texts, so to speak, but concerned many artists, in literature—J.L. Borges for example, whom he met; in cinema—Chris Marker, whom he knew well and quoted in his work; in painting—Magritte, whom he often commented on. Text and image were, for Legendre, inseparable. He cherished and quoted a formula of Saint Augustine: without knowing it, man “walks in the image,” starting with his own.

Legendre’s books are, for this reason, full of images, from medieval paintings to more recent advertisements. This is not an artificial juxtaposition or gratuitous erudition; it is a way for him to show how the thought structure of a society is transmitted across generations, or beyond the medieval melting pot. From the beginning to the end of his work, his task was to detect the structure of the invariant beyond the variations.

Among Legendre’s references, one can also think of Gratian, a great jurist scholar who compiled biblical, patristic and legal texts in the 12th century. Closer to home, we can better understand Legendre by thinking of the figure of Paul Valéry: philosopher, poet and writer. In short, Legendre’s references were always other encyclopedists combining science and poetry; whatever their personal approach and the historical moment of their work.

PL: During the last twenty decades of his work, Pierre Legendre paid particular attention to young students, to whom he devoted certain essays. The Introductions, on the other hand, also testify to the diverse receptions of his work. Did Legendre seek to become a school, or at least to have an intellectual posterity?

PM: Pierre Legendre was concerned with his heritage, it seems to me, since his first film, La fabrique de l’homme occidental, that is, since 1996. The film, when I showed it to my Master’s and DEA students at the Sorbonne, was a revelation and an enlightenment for many. The documentaries that followed, the small books he published after conferences at the École des Chartes (L’inexploré [The Unexplored], 2020) or at the Lycée Louis le Grand (La Balafre: À la jeunesse désireuse [The Scar: To the Desiring Youth] 2007), for example, where he addressed a young audience, also prove that. His latest works show a concern for popularization, insofar as his work and his style are often dry and difficult.

Nevertheless, Legendre’s first concern was that of transmission: to transmit the enigma of why? The great schools and universities bathed in positivism and scientism are primarily interested in efficiency, in performance; everything appears transparent and clear. Another anthropologist, Georges Balandier, also noted that the West is in a “technological and scientific hyper-power” that avoids the economy of the why, in other words a power without meaning. Legendre left, in his own way, the same message.

Moreover, we now see international readings of Legendre, cultural appropriations of his thought. The Introductions show it well: a great scholar like Osamu Nishitani, in spite of the complexity of understanding the West from Japan, has an original and profound apprehension of Legendre’s thought. The same is true of certain German and Italian scholars. The borrowings—I spoke earlier of plundering—sometimes give way to real appropriations. Like a Michel Foucault, Legendre will in my opinion be truly recognized when he is more widely translated into English. That is also what the West is all about. That is why Legendre preferred to conduct his scholarly conversations in Latin.