Dreyfusard, but a friend of Saint Joan of Arc, a socialist, but discovering from experience that socialism is a dangerous and unattainable thing, an anti-militarist who loved the military profession, an anticlerical whose conversation is with the saints who have made France sweet and who found in Our Lady of Chartres the appeasement of his heart.

Charles Péguy, polemicist, poet, mystic, doesn’t fit into any category. But even in the midst of his contradictions, he remains a Frenchman of peasant and working-class descent, of old France. To each of the great crises of the time, he reacted in a very personal way, which may not be our way, but is, as if in parallel, to use an image he loved. Let us try to better understand who Charles Péguy was and to retain, beyond his prejudices and inconsistencies, the best of what he had.

The Gamut Of Influences

Charles Péguy was born in Orléans on January 7, 1873, in the faubourg of Bourgogne. His father, a carpenter, died on November 18 of the same year from an illness he had contracted at the siege of Paris.

The child grew up with a very active mother and a grandmother who was a bit lame. As an only child raised by women, he was the center of attention. The charming child listened to the advice about life that his mother gave him, and he liked working with her a lot. Intelligent, studious, he applied himself to his lessons as well as to his prayers. Such was considered good work, a quality of old France, as of the faubourg of Bourgogne. Péguy would write: “One can say that a child raised in a city like Orléans, between 1873 and 1880 [as he was], has literally touched the old France, the old people, the real people, that he has literally participated in the old France of the people.” These two women were Catholic, and little Charles attended catechism; but the family was not particularly fervent, and worked on Sundays.

In 1880, he entered the Republican elementary school. He was marked forever. He discovered another world: The hierarchy of education, but also republican ideology. He was noticed for his intelligence and his hard work. In 1885, he entered the high school at Orléans with a scholarship.

Thus, in parallel with his religious instruction – catechism and solemn communion – he came into contact with all the classical culture, breathing in this secular atmosphere, impregnated with the ideas of 1789 that were inculcated in him by the men he admired, his teachers, all proselytizers of the socialist ideal.

In 1888, when he was 15 years old, the athletic high school student was on the horizontal bars when he had a fainting spell and fell on his head. It was nothing serious – but from that moment, his character changed; he became whimsical, imperious; he became impulsive, made sudden decisions, was inconsistent in conduct. His whole future life would be marked by hastiness, by a readiness to get angry with people, the cause of which might well be this blow to the head.

That same year, the deeply socialist, irreligious Péguy was born. In 1900, he confessed: “I was in high school when I became a heretic.” He chose the Revolution against the Church, which he considered a superstructure of the bourgeois world. He broke with the faith because the dogma of eternal damnation was intolerable to him and because Christians seemed to accept it with an unseemly resignation. He was not in favor of the class struggle, but he considered that the modern world (which began in 1881) was made up of an opposition between the hypocritical, selfish bourgeoisie and the people.

In 1891, after passing his baccalaureate, he entered the Lycée Lakanal to study for the École normale supérieure. This was the way into the agrégation in philosophy. But he failed the oral exam and was called up for military service a year sooner. This fervent anti-militarist loved the army – the discipline, the order, and the attachment to France; and the military profession appealed to him from the start.

When his year of service ended in 1893, he resumed his studies at Sainte Barbe. There he met the friends he would keep all his life. He exerted a real influence over his fellow students who felt dominated by him and considered him as a leader. Péguy was that very type of militant who fought others to support those on strike, for there was always a strike somewhere and Péguy always needed money. Daniel Halévy tells us: “All he had to do was to hold out his hand and pockets were emptied immediately.”

He was therefore a utopian and apostolic socialist. For him, socialism was the new world, the better future, the liberation of the people. It was the place of dreams, where the idea of solidarity, of an absolutely universal solidarity between men, could develop without limits.

He entered the Ecole normale in November 1894. He worked hard. He learned with wonder the Latin, Greek and French authors who would deeply affect him. He made contact with the professors, the great politicians of the Radical Republic: Lucien Herr, the socialist librarian who had sought this position as the best one for converting the University to socialism; Jean Jaurès, professor of philosophy. He was very close to another student, Marcel Baudouin, who died in 1896. The dead friend would always shadow him throughout his life.

In October 1896, he wrote his first socialist articles. The following year, in 1897, he married the sister of his friend Baudouin, probably out of loyalty. Frenzied Dreyfusards, militant socialists, the Baudouins were the very type of bourgeois who sponsored the revolution. None of the children was baptized. His marriage was therefore civil. In December, he published, at his own expense, after having begged friends, the drama he had just finished, his Joan of Arc, the heroine of Orléans whose life he had resolved from childhood to write, “for the establishment of the universal Socialist Republic!” He sold only one copy!

In January 1898, Zola’s J’accuse in the Aurore re-launched the Dreyfus affair and threw Péguy into the fray, convinced of Dreyfus’ innocence by Lucien Herr. Certainly, Péguy never offered one fact explaining why he favored Freyfus, proof on which he could establish his innocence. Péguy believed that the General Staff and the Justice system had condemned Dreyfus because of anti-Semitism. The country was therefore in a state of mortal sin.

Having failed the agrégation, Péguy abandoned the university. With his wife’s dowry, he bought a small bookshop in the shadow of the Sorbonne, which became the center of Dreyfusian agitation. All the socialist academics, the staff of intellectual Dreyfusism, met there. When the fight at the Sorbonne broke out, Péguy rushed in and fought against the nationalists, taking the lead of the Dreyfus commandos.

But the business-venture did not succeed. Lucien Herr proposed to bail out the business, with the help of Léon Blum. But, in fact, Péguy was ousted. He found himself no longer the owner but the employee of these gentlemen, a manager of a limited company. Péguy, being overly honest with himself, felt a pang of sorrow, seeing himself thus played out financially; but he will never realized that Herr had deceived him even more intellectually by making him believe in Dreyfus’ innocence.

An Honest Socialist

In 1899, a cascade of political and personal events put an end to this candid period of his life. Péguy woke up.

For Péguy the prophet, Dreyfusism was a religion. But when he learned that Dreyfus accepted his pardon, that is to say, recognized himself guilty, it was a terrible shock for him. Péguy lost his illusions and he realized that the Dreyfus party was a party of political jackals, ambitious and calculating.

Then, another shock. Péguy wanted to publish a novel telling the misfortunes of a teacher who ends up committing suicide with his wife. For Péguy, this was the very type of popular misery for which the socialists must fight for, against society. But Blum and the others sent him packing, because the unfortunate protagonist had fallen into misery, not because of the aristos and the army, but because of the republican administration. Péguy saw in this experience the proof that these socialists thought only of making a career and not of relieving the poor.

Finally, there was the affair of the Socialist Congress of December 1899. Péguy came out of it disgusted by the decisions taken, which made the socialist press subservient to the central committee. Guesde, Blum and the others only had in mind the seizure of power and not the defense of the truth. Péguy resisted, Herr called him an anarchist. Péguy lost everything, his job, the publishing house he founded and those he thought were his friends. He had a wife and child and found himself alone, without support or money.

He overcame his misfortune and founded a new publication, his own journal. The first issue of Cahiers de la quinzaine was published on January 5, 1900. It was no longer a question of serving socialism as it had been in the past, but of “telling the truth, nothing but the truth. Telling the stupid truth stupidly, the boring truth boringly, the sad truth sadly: That is what we are going to do… To the good bourgeois and also to the comrades who want to take refuge conveniently in silence. Didn’t we often cut off retreat, saying brutally: He who doesn’t shout the truth, when he knows the truth, makes himself an accomplice of the liars and the forgers.”

Possessing a righteousness which knew nothing of compromise, in 1902, he asked Bernard Lazare for a defense of the congregations persecuted by Combes and Jaurès, and he got it. Shortly afterwards, however, he was reproached by this same Bernard Lazare for his reversal, reminding him who was supporting him financially. Péguy did not think that the Jewish party which sponsored him, which subscribed to the Cahiers, intended him to follow its feelings when they were not necessarily about justice and truth.

1905 represented a turning point in Péguy’s life. It was the Tangier Crisis, where Kaiser Wilhelm II claimed his rights over Morocco to drive out the French, while demanding the dismissal of the French Minister of Foreign Affairs. This awakened Péguy. He saw the war coming. He became aware of the danger. Faced with the threat, seized by the angor patriae, he felt French first. He led his socialist and pacifist readers to patriotic emotions in that admirable issue of Cahiers, Notre patrie (Our Fatherland):

“At the first outbreak, at the first intonation, every man heard, found, felt within himself this profound resonance, as if familiar and known, this voice which was not a voice from without, this voice of buried memory, as if piled up deep within for who knows how long.”

This “voice of buried memory” awakened in the child of the Bourgogne faubourg the feeling of patriotism, and it began its work of spiritual conversion. Christianity gradually penetrated his heart and his thought, because the soil, all the dead, the very soul of France is Christian, steeped in Catholicism.

Following Notre Patrie, he published Les suppliants parallèles (The Parallel Suppliants), an admirable meditation on the seizure of the supplicated by the supplicant. His faith found its platform here.

Péguy understood then that “for the Catholic faith the eternal hell of religion has nothing to do with, and even is the opposite of, the temporal hell of the exploited, the humble, the poor: That it is not made for the damned of the earth but for their exploiters.”

Conversion

It was most certainly in 1906 that Péguy returned to God, receiving the gift of tears and prayer. He then experienced a period of intense blossoming and literary and mystical fruitfulness. And it was in January 1907 that he announced his return to God to Maritain, and in September 1908 to Joseph Lotte, the most faithful of the faithful.

As he wrote in Clio, one of the Cahiers: “He found the being that he was, and he found in that being the being that he really was, a good Frenchman of the ordinary kind, and towards God faithful and a sinner of the common kind.” That is why he did not want anyone to talk about his conversion, for he considered that he had always been a Catholic. “I am not a convert. When one has learned the catechism like me in the parish of Saint-Aignan in Orléans, one does not have to convert. For a while my eyes were turned away from God; they have turned back. That’s all.”

He did not make an official announcement of this conversion (which must be called that). It was gradual, a secret. Péguy’s attitude in fact baffled his Catholic friends, who found his Catholicism bizarre, a Christianity without the Mass and without the sacraments. He said to Maritain, the Mass and the Communion, that is “too strong for me.” But he prayed and with much consolation. Returning to God, he found popular religion and he lived among the saints, who were alive and present.

Family life was not very cheerful. Cahiers, always in the red, was a perpetual ball and chain to be dragged along, and money difficulties troubled home life. The three children, not baptized obviously, being socialist atheists, were Baudouin, all of them, nothing of Péguy, he would confide. He felt a stranger, all by himself. His mother-in-law, cemented in her impiety, lived with them.

Péguy, a convert, lived with his wife from the legal point of view, but from the religious point of view, she was not his wife. He could send her away or present a request to Rome which, as far as he was concerned (since his unbaptized wife refused any such regularization) would be equivalent to a religious marriage. Likewise, he had the duty to ensure the baptism of his children. Since his wife did not want it, he could have baptized them without her knowledge. In his loyalty, because he did not like to force, Péguy did not find any of these solutions practical. The situation was hopeless. He remained a good husband, a good father. As for himself, he had his intimate, catholic, praying soul – but not being able to approach the sacraments.

He fell sick from all this. His household also fell sick.

During these years (1907-1909), he fought against the radical-socialists in the Sorbonne, and he announced the end of our culture. This polemic pushed him, in a new series of Cahiers, to oppose the modern world of un-culture, of jealousy, and to exalt the ancient world, namely, Christian France, and beyond it the success of the Greek world. He understood that our time needs mysticism, and as much a sinner as he was, he felt invested with a mission – that of remaking Christianity through prayer.

In 1909, his Mystère de la charité de Jeanne d’Arc (Mystery of the Charity of Joan of Arc) was published, the first public manifestation of his Catholicism. It was a half success, but which did not improve his material situation.

The Drama Of His Life

It was in marital disagreement and in its inextricable material embarrassments, that Péguy came to know passion. A love appeared which ate his heart for eighteen months.

In 1910, Péguy noticed Blanche Raphaël, the sister of one of his friends, a former Sorbonne classmate, who was very helpful in the Cahiers store. And Péguy fell in love with her. It was a terrible temptation which reached its climax during the summer of 1910. This upright man, so very focused, who exalted justice and fidelity, experienced a crisis of the soul. The struggle exhausted him. He reproached himself for the temptation to divorce as a disloyalty to his wife and children. Le porche du mystère de la deuxième vertu (The Porch of the Mystery of the Second Virtue), laid bare the secret of a father’s torn heart. It tells how “the father’s kiss” is a game for the children, an amusement to which they hardly pay attention. It’s so habitual. They get it like a piece of bread. “But for the father, the father’s kiss, it’s his daily bread. If they only suspected what the kiss was to the father.”

The poor dears.

But it’s none of their business.

They have plenty of time to find out later.

They only find, when their eyes meet the father’s gaze, that he doesn’t seem to have enough fun in life.

This paternal kiss was the sacrament that bound him to his children. It was what kept him from betraying his wife. So, he prayed and he worked. But for eighteen months he could not say the Lord’s Prayer. He confessed on September 27, 1912 to Lotte: “’Thy will be done,’ I could not say that. It’s not a matter of just muttering through it; it’s a matter of really saying what you say. I couldn’t really say, ‘Thy will be done.’” So, he boldly addressed the one who is infinitely pure, because she is infinitely sweet. God is just and strong, the Virgin Mary is tender and merciful. He continued to tell Lotte: “So I prayed to Mary. Prayers to Mary are prayers of reserve. There is not one in the whole liturgy, not one, you hear me, not one that the most miserable sinner cannot really say. In the mechanism of salvation, the Hail Mary is the last resort. With it, one cannot be lost.” He then affirmed: “It is the Blessed Virgin who prevented me from sinning.”

He then took the decision that cost him terribly, that tore his heart, and he sacrificed his happiness to honor, since the true name of this happiness was dereliction and sin. And he saw the young woman marry [to Marcel Bernard], putting one more obstacle to his passion. In September 1911, she had a child, and he felt devastated. He wrote Le Porche, on the virtue of hope, but “it is an anticipation, for when I wrote it, I did not believe in hope.”

One day in June 1912, when he could no longer bear it, he went to Chartres to entrust his aching soul to the Blessed Virgin. It was his first pilgrimage to Chartres, the one he made on foot. Our Lady performed the miracle, won the victory. “Our Lady saved me from despair,” he said. Let us take up this intimate letter to Lotte:

“I cannot explain to you… I have treasures of grace, an inconceivable superabundance of grace… I made a pilgrimage to Chartres. I am a Beauceron. Chartres is my cathedral… I walked 144 km in three days. Ah, my old man, the crusades were easy!… You can see the Chartres bell tower from 17 km out on the plain. From time to time it disappears behind a wave, a line of woods. As soon as I saw it, it was an ecstasy. I didn’t feel anything anymore, neither the fatigue, nor my feet. All my impurities fell away at once… I prayed, old man, as I have never prayed before.”

The prayers written on her return, in thanksgiving and in the enthusiasm of the favors received, which form La tapisserie de Notre-Dame (The Tapestry of Our Lady), allow us to guess the drama of “this old heart which was rebellious” and of “this young child who was too beautiful” and how salvation came because Our Lady of Chartres “is the place in the world where everything becomes easy,”

Here is the place in the world where temptation

Turns itself inside out.

For what tempts here is submission.

In Chartres, conversion is easy, the heart turns away from earthly things because the Blessed Virgin is there, offering her love, with tenderness and maternal solicitude. The second prayer does not ask for happiness: “O Queen, it is enough for us to have kept our honor;” and under her command “a fidelity stronger than death.”

The third prayer, “Of Confidence,” describes the drama, the choice of suffering. It is all the tragic aesthetics of the man put “in the center of misery, placed in the axis of distress.”

The fourth prayer delivers to us an upsetting secret. Péguy recalls his ordeal, and he asks the Holy Virgin to transfer her graces of happiness and prosperity on four young heads. Péguy had only three children, so if he speaks of four, it is because he could not help but think of that young woman’s little daughter, Blanche Bernard, as his own.

The love of the Blessed Virgin turned him away from any other forbidden love and made him find the Holy Hope which is to accept what God wants for us.

With this key, we understand his Présentation de la Beauce à Notre-Dame de Chartres (Presentation of the Beauce to Our Lady of Chartres). Everything is symbolic. Péguy became a child of Mary again and could once more say the Lord’s Prayer, along with the Hail Mary.

After a last pilgrimage to Chartres, in July 1913, he composed a fifth prayer, Of Deference, in which he wrote a definitive resolution: He will only accept in his heart a love that wants to give itself up to the Virgin Mary. These texts reveal to us that in Chartres, Péguy reached the highest mystical peak of his existence after a crisis that shook his whole life, and at the same time the highest peak of his poetic art.

It is admirable how this man overcame this terrible temptation, this torment. In 1910, he overcame it and matured for his great works. What would have become of him, if he had left his wife and children – canon law would have allowed him to do so – and all for a young Jewish woman whose face and intelligence fascinated him? Péguy would have been nothing – whereas he now teaches us that great things can only be built on sacrifice.

After this “secret of Péguy,” he went to work, since “there is plenty of work that advantageously replaces happiness.”

The Great Works

Indeed, these crucifying years became grand period in which his genius blossomed, through the drama of his intimate life, but also intellectual solitude. He was angry with the political framework of socialism because he wanted to remain faithful to the syndicalists. He was angry with his friends for trifles, Maritain, Sorel, Halévy. Péguy was of an atrabilious tendency. There was some Rousseau in him – chagrined susceptibility, continual concern to put himself forward, to talk about himself (his health, his works, his debts), permanent concern for the examination of conscience and public confession, the need to air his quarrels in the street with perfect bad taste – thus notes René Johannet. Moreover, two manias tormented him: That of never misjudging, while being contrary, and that of breaking off from others, while complaining of having been left out! Perhaps this ever-ready quarrelsomeness, these contradictions were caused by the fall he had on his head. His photos show the relentless gaze of a man whose life was a constant failure.

Notre Jeunesse (Our Youth) appeared in July 1910. His friend Halévy had just written about the Dreyfus Affair as an old story in which people had been misled, since, under the cover of the revision of the trial, a cynical gang was engaged in the ransacking of France. In three weeks, Péguy wrote a response to Halévy, Notre Jeunesse. He contrasted the pure Dreyfusists, men of eternal salvation, with their adversaries, men of temporal salvation, not to mention criminal politicians; and he concluded peremptorily: “Everything begins in mysticism and everything ends in politics.”

The irreducible opposition that Péguy instituted between mysticism and politics was first of all the cry of a deceived heart, the outrageous conclusion of his unfortunate involvement in a political movement in which his mysticism, itself noble and generous, had served as a cover for a low maneuver of anti-militarist, anti-French, anti-clerical subversion, and the conquest of Power in opposition to his ideal. In fact, the Dreyfusist mysticism of the pure degenerated into the politics of treason. But there is no intrinsic necessity to this deception, to this detour – politics can therefore still be one of the providential places for the exercise of Christian mysticism, for the establishment of the Kingdom of God. For lack of understanding this, Péguy could not get along with Maurras.

This masterpiece of polemics, in particular against Jaurès, ends with the admission of Dreyfus’ disqualification. He had disappointed everyone.

Halévy, the friend of 15 years, got angry. To reconcile him, Péguy wrote, Victor-Marie, Comte Hugo – “I beg your pardon, I will not do it again,” he explained to Halévy. “But I have offended you because I am the people and you are bourgeois!” Then, from the political register he passed to the literary register. In his triple parallel of Hugo, Corneille, and Racine, Péguy showed himself a great critic. This Cahier ends with the praise of his friend Psichari, a magnificent patriotic officer in Mauritania.

Attacked for his faith, Péguy retorted violently in another Cahier, Un nouveau théologien, M. Fernand Laudet, in September 1911. Confronting the career Catholic, the incarnation of conservatism, a “man who would sell his God in order not to be ridiculous,” Péguy rigorously affirmed his faith, the one that was all in the catechism: “Our loyalties are citadels. These crusades which carried off people, which threw continents one on top of each other, have been transferred to us, they have returned to us… The least of us is a soldier. The least of us is literally a crusader.” His Christianity reached its peak with Le porche du mystère de la deuxième vertu (The Porch of the Mystery of the Second Virtue), which appeared in October 1911. In it, we see his entire life of despair transcribed into obscure terms.

Le Mystère des saints innocents (The Mystery of the Holy Innocents) followed in March 1912. The crisis of despair was overcome, even if he still had yet more terrible days to face. He sings of his reconciliation with the Father. He allows us to see, with the eyes of God the Father, so to speak, an immense flotilla of prayers loaded with the sins of the world which attacks God the Father and forces Him to have mercy.

Péguy continued to do everything at once, to produce without respite, while the disaffection continued – the chase after the great prize of literature of the French Academy, but Lavisse and Herr were opposed to it.

In August, his little Pierre was stricken with diphtheria. He went to Chartres, to entrust his child to the Holy Virgin. “My child is saved,” he wrote to Lotte. Touched by this healing, Mrs. Péguy agreed to have the child baptized, but Péguy, caught up in the business of a friend, did not immediately respond to his wife’s request. She reneged; he let the opportunity pass him by.

With La tapisserie de sainte Geneviève (The Tapestry of Saint Genevieve), published in December 1912 and dedicated to the very anticlerical Geneviève Favre, he launched into verse.

Péguy began to be famous. He was fundamentally and publicly Catholic; a nationalist without using the word; a socialist who preached France and armament, ready to go to war against the barbarians. He continued to rage against Jaurès, the pacifist internationalist, who did the dirty work of Germany and demoralized the French. He dreamed of mobilization, “determined to cover himself with glory.”

L’argent (Money) and L’argent suite (Money Continued) came next and illustrated the power of the polemicist. “Louis XVI was good. That is not what one asks of a government. What is required of a government is to be firm.” He was anti-parliamentary, anti-democratic: “The weapons of Satan are the shouting, the vote, the mandate and suffrage.” Such quotations abound: “One must not be for the small. The little ones are the weak. You must love them, the little ones. Serve them, the little ones. Protect them, the little ones. But you must not be for the little ones. Who will protect them, serve them, love them, if not force? You have to be for force. You have to be for the big ones.”

He found a way to unite in France his three passions: The ancient world, the Christian world and revolutionary liberty: “France has two vocations in the world – her vocation of Christianity and her vocation of liberty. France is not only the eldest daughter of the Church; she is undeniably a kind of patroness and witness (and often martyr) of freedom in the world.” (L’argent suite).

L’Argent suite explained that our religion is the religion of the God who became man, of the spirit and of the flesh. Péguy wants Christ to reign on all levels of being, in the spirit and in the flesh. Seized by the shock of the Incarnation, he felt what is complete in our Christianity. There is no Christianity without Catholicism and patriotism. Let us not misunderstand the mysticism that degrades into politics. All his work affirms and demonstrates that there is no true mysticism that does not lead to politics, that does not command a politics; just as conversely there is no spiritual salvation that is not supported and measured and induced by a temporal salvation. This is one of the most striking and important aspects of his message.

In May 1913, he published his Tapisserie de Notre-Dame (Tapestry of Our Lady), the fruit of grace of his pilgrimages to Chartres where he returned in July.

He was 40 years old; he felt old; he sensed death. He knew that he was moving towards the most perfect of achievements, towards two glories united in one, that of the soldier, that of the believer, walking to sacrifice.

On December 28, 1913, Eve was published. It is a Catholic work, where Christ shines in his cosmic monarchy. Péguy was extremely proud of it, with reason. Ten months later, these verses became the very poem of the war. He knew that he was part of this multitude whose sacrifice he sang. But just imagine the fright of the subscribers of Cahiers when they received this monster of 400 pages, containing 1911 quatrains! Especially since in the middle of great, beautiful verses, in the middle of the confidences of Péguy, of envois to the dead soldiers, there are entire pages of metric verbalism and sound.

It was a disaster for Cahiers. The unsubscribing that immediately followed was the greatest joy for the enemies of Péguy. This fiasco was revenge for them for L’argent suite.

There were still more polemics; this time in favor of Bergson. In June 1914, he finished a meditation on history, on the decline, in the Cahier entitled Clio, which was not published until 1917. Here extremely rich ideas abound. Péguy speaks of himself as a man close to death. Since 1905, he saw the war coming. From 1912, he went ahead to lead this war that he so desired.

Péguy: Soldier And Christian

On Saturday, August 1, the mobilization was posted. Before leaving his pregnant wife and children on Sunday, August 2, he talked to her about the future. His wife asked him: “What will I do about this child?” She asks about baptism. “You will think about it,” Péguy replied enigmatically. Then he added, “If I don’t come back, I beg you to go every year on pilgrimage to Chartres.” He passed on to her the resolution he had made for himself.

“I must see my friends,” he said to his wife as he left her to go to Paris. He went to Madame Favre’s house, where he met Blanche Bernard (Blanche Raphaël] who was afraid of the war. To encourage her, he explained the reason for the war, and when he left her, he said: “If I don’t come back, you’ll go to Chartres every year.” And he did not come back.

He saw his friends again because he wanted to be reconciled with them: “The main thing for me,” he said, “is to leave with a pure heart.”

Everything was simple in this new life he was entering. He lived in a “kind of great peace.” He wrote to his wife on August 7, “I didn’t think I loved you intensely. Live in peace as we do here.”

His physical Catholicism, his love of the fatherland led him to danger, to dedication. The man of perpetual anger became a leader, loved by his men; and he took his place in the middle of the procession of poilus, soldiers and generals. During the 33 days of his war, he never ceased to be admirable.

Péguy, this peasant, this philosopher was above all a soldier. He commanded the 19th Company of the 276th Infantry which left for the front. Testimonies are numerous about his energy, his endurance. He seemed tireless, unaffected by the heat; always the first to go to his post, without any concern for danger.

On August 15, he heard the Assumption Mass in the little church in Loupmont – his first Mass.

The General congratulated “the 19th Company of the 276th infantry regiment for its fine attitude and its retreat in perfect order under machine gun fire during the battle of August 30.” In spite of the bad news, Péguy still believed in victory. Johannet wonders: “What was about this little man to make him stronger than fatigue, heat, hunger, discouragement? He had behind him 2000 years of courage, and he put the seal of sacrifice and blood upon it.”

On September 5, near Villeroy, Péguy led his battalion into its first battle, one of the first battles of the victory of the Marne. He shouted, “Forward!” His captain was killed. He continued the assault. Still standing, he yelled, “Fire!” He fell, struck in the forehead, among his soldier people about whom he so well sang: “Soldier people, says God, nothing beats the Frenchman in battle.”

Péguy himself had composed their funeral oration in Eve:

Happy are those who died for this common earth,

But only if it was in a just war.

Let us conclude by preserving the best of Péguy: Here is Péguy, the man full of contradictions, who passed through the most absolute revolutionary atheism and ended up with the purest patriotism and Catholicism. His attachment to France was profound. Now, the soul of France, the wealth of France, is first of all the devotion to the Virgin Mary of which all these cathedrals are the proof. France is the kingdom of Mary.

Our Lady has kept well those whom Péguy entrusted to her, family and country. Mrs. Péguy was baptized along with her children, except Marcel, the eldest. The terrible war was the regenerating ordeal of those who were called the “sacrificed generation.”

Sister Bénédicte de la Sainte Face write and comments on the Catholic faith in France. This article appears through the kind courtesy of La Contre-Réforme Catholique au XXIe siècle.

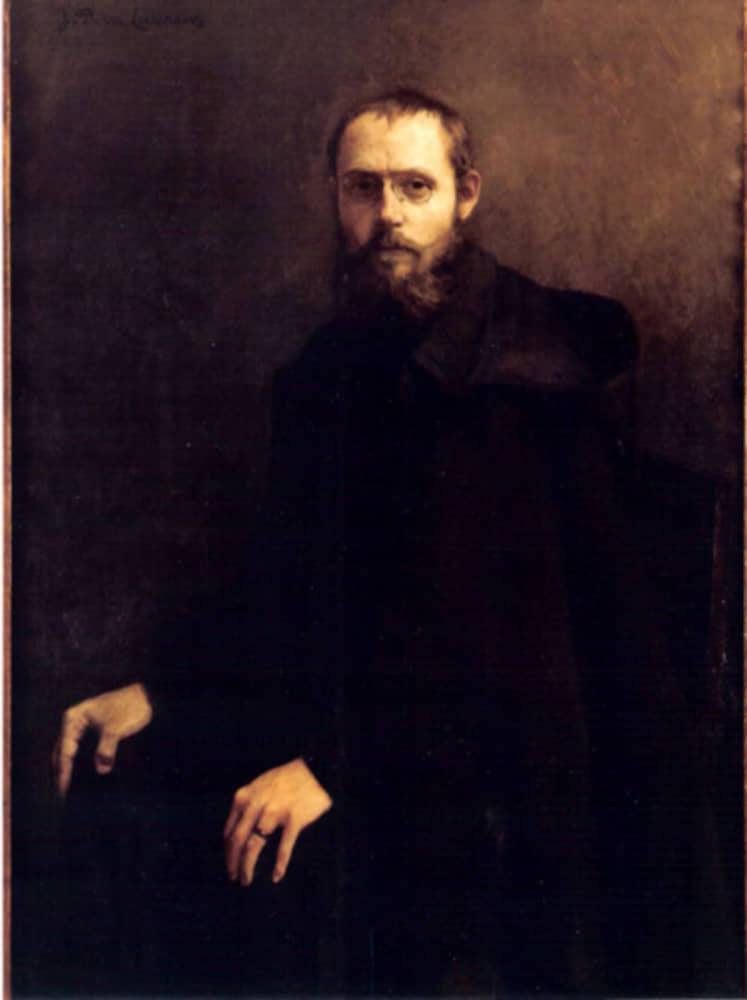

The featured image shows, “Portrait of Charles Péguy,” by Jean-Pierre Laurens; painted in 1908.