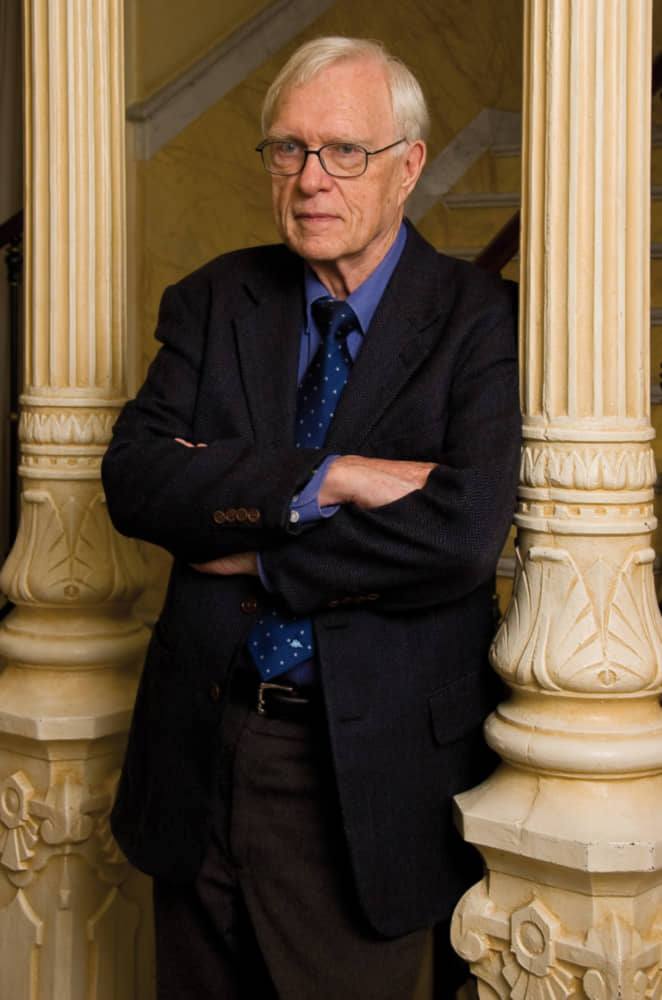

It is a great privilege to have had a conversation with Professor Stanley Payne, the foremost Hispanologist of our time, which we are delighted to bring to our readers. Professor Payne is the Jaume Vicens Vives and Hilldale Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He has authored several important books, including, A History of Fascism 1914-1945, The Spanish Civil War, Franco and Hitler: Spain, Germany, and World War II, and Franco: A Personal and Political Biography.

The Postil (TP): Please tell us a little about your own personal history. Was there a single event, or even a series of events, which shaped you and your career?

Stanley Payne (SP): There was nothing distinctive, cosmopolitan or noteworthy about my early life. I was born in the small town of Denton, Texas (between Dallas and the Oklahoma border) in 1934, and I was what would later be called a “Depression baby.” We certainly lived in modest circumstances and in 1944 joined the wartime migration to California, where I finished growing up. I was given a Christian education, largely Seventh-Day Adventist, but left that faith while still a teenager, partly due to its fantastic interpretations of the Bible. I returned to Christianity only after my marriage at the age of twenty-six. My general upbringing, I would place within the broader context of Anglo-American Calvinism, and there was nothing in that to prepare me for a life dealing with the Hispano-Catholic world. This sectarian, non-conformist background did perhaps prepare me to be more independent rather than merely following the most conventional patterns.

TP: What brought about your life-long interest in Spain?

SP: There was almost no Hispanic influence at all in North Texas in those days, but in 1943 the Texas Board of Education ruled that all children should receive some sort of language instruction from the fifth grade on. I developed an interest in Spanish and later minored in the language as an undergraduate. Around the age of 19-20, however, my main focus lay on Russia, though I had no opportunity to study the Russian language. In 1955, when I entered graduate studies at Claremont University, Russian history was not an option. That summer I read The Spanish Temper, by the British literary critic and avocational Hispanist, V. S. Pritchett, a work that strongly appealed to my imagination and first gave me the idea that the history of Spain—then virtually unexplored outside that country—might be both interesting and important. Moreover, I had academic advisors—the Latin Americanist Hubert Herring at Claremont and the noted Franco-Italian specialist Shepard Clough at Columbia—who encouraged me to become in effect an autodidact in this new field.

The history of Spain is absolutely extraordinary and is generally misunderstood, more than that of any other Western country, but I have never considered myself a mere “Hispanophile,” despite my dedication to getting its history straight. Modern Spain has been unusually divided and conflictive. The Spanish are regularly misconceived as “individualists,” which is a misnomer. They are better described as factionalists who exhibit great loyalty to factions, local groups and regions, and often express limited individualism. One may speculate that this is due to a lesser impact in Spain of the medieval Roman Catholic insistence on exogamy, compared with other Western countries. If that were so, it would be an ironic commentary on “Catholic Spain.”

An important and attractive aspect of Spanish culture and society is the great value placed on friendship, a relationship especially cultivated in that country. My Spanish friends have been very generous and helpful, and I owe much to them, as does all my work. It is important to me always to acknowledge their assistance.

TP: As the foremost historian of twentieth-century Spain, where would you locate yourself within the tradition of historiography? Is there a school of history that you naturally align with?

SP: My work has followed the general methodology and style of Anglo-American empiricism, within the framework of national histories and comparative European history, but follows no special school or trend. My initial mentor in Spain was the great Catalan historian Jaume Vicens Vives, who was both Catholic and Catalanist but certainly not a mere “nationalist historian.” Vicens was a critical empiricist who was revisionist in the best sense of the phrase, and also came to emphasize the kind of social and economic history that previously had been largely ignored in Spain.

TP: We live in a time which has a rather fraught relationship with the past, a time which seems to want to overcome history. How do you respond to the current vogue of presentism? Is it a passing phase? Or, does it portend something darker?

SP: At the present time infinitely more is known about history than ever before, but contemporary culture and education devalue and ignore the study of history in a manner totally unprecedented in the history of Western civilization. Many factors contribute to this, one of them the quasi-religious character of contemporary progressivism, which seeks to annul comprehension of the past in favor of a timeless future utopia of pure virtue. This is the expression of a kind of millennialist attitude, which probably has some distance to go.

TP: Your many and magisterial books on Spanish history have analyzed the period from 1917 (when the constitutional monarchy collapsed) to the government of Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923-1930), and the Second Republic (1931-1939), during which was fought the Spanish Civil War. Why are these two decades in Spanish history so important?

SP: Modernization, particularly as economic transformation first became a major problem in seventeenth-century Spain, but the early transition to liberal politics in 1810 initiated a century and a quarter of intermittent political convulsion. Both dimensions merged to produce two decades of intense political and social conflict—paralleling the great European political Kampfzeit of the interwar period in the past century—that served as the conflictive climax to this era. No other country both achieved temporary democracy and also employed it to tear the country apart so thoroughly.

TP: Your profound work on fascism and Spain is certainly paradigmatic. What led you to focus on this aspect of Spanish history?

SP: The initial choice was almost serendipitous, in that it had nothing to do with “fascism.” I simply had to find a topic to initiate graduate research, and Hubert Herring suggested the figure of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, which struck my fancy. I had no intention at that moment of focusing on “fascism,” which I would scarcely have been able to define. But one thing led to another. I rather grandiosely subtitled the eventual book “A History of Spanish Fascism,” which it really was not.

TP: The term “fascism” is much bandied-about nowadays. Is there a proper way that we should understand it?

SP: In the 1950s, when I began, any concept of fascism was simplistic. All work was monographic or national in character, but failed to solve the greater issue of “fascism” in general, and that led to the international “fascism debate” of the 1960s and 70s.I participated in the latter, perplexed about the problem of how to define and analyze a “generic fascism,” if any such thing existed. I finally managed to work this out in my Fascism: Comparison and Definition, which appeared in 1980, the first book to present a systematic and detailed definition and analysis of the problem. This stemmed from my concern to make major Spanish developments—fascism or revolutionary civil war, for example– understandable within a broader comparative historical framework.

In the twenty-first century “fascism” has become a meaningless term, an “empty signifier” that serves as all-purpose pejorative and stigmatizer without serious cognitive content. Academic specialists, including myself, employ the term as an “ideal type” construct to refer exclusively to the revolutionary nationalist movements in interwar Europe, which had specific characteristics of their own that have not subsequently been repeated to any significant degree as composite features, and probably cannot be. Fascism was destroyed militarily in 1945 and then became subsequently superseded by massive historical change, which made it impossible to develop equivalent movements in radically differing contexts.

TP: Your first book, Falange: A History of Spanish Fascism, reads like a great Greek tragedy. Could you briefly describe the Falange and its spirited and tragic leader, José Antonio Primo de Rivera?

SP: Falange was the only true “fascist-type” movement in Spain, composed of young radical nationalist activists reacting to the anti-nationalist revolutionary process in Spain, where what passed for fascism was in consequence more clearly counterrevolutionary than in any other country. The Falangists were serious about their radical national syndicalist socioeconomic program, but in a country of secondary importance such as Spain, how this worked out was going to depend in large part on geopolitics.

I have said elsewhere that José Antonio Primo de Rivera has managed to become “everybody’s favorite fascist,” the least fascistic of all the European national fascist leaders and the one most nearly attractive as an individual. As observed by some of his rivals, such as the key Socialist chief Indalecio Prieto, his personality did not fit the fascist type. In the case of José Antonio, it was a matter of hereditary politics, since he was the eldest son of Gen. Miguel Primo de Rivera, the moderate dictator of the 1920s, virtually the only bloodless European dictator, who earned the grudging respect even of some of his enemies. José Antonio felt that he must vindicate authoritarian nationalist politics in Spain to complete his father’s work but did not fully understand the extent of the radicalization to which he himself was contributing. His own interests were more literary than political and he even considered resigning in favor of a leftist leader willing to adopt Spanish nationalism. So there are two schools of thought regarding the “good” and the “bad” José Antonio. The noted French intellectual Arnaud Imatz has written the best favorable account, and the Catalan historian Joan María Thomás the best critical biography.

TP: Looming behind all this, of course, is the Spanish Civil War, about which you have written extensively. Briefly, what led to this conflict? And how should we understand it?

SP: The Spanish war was the great European conflict of the years preceding World War II and often drew more comment than the rise of Nazi Germany. It became a mirror of current politics, in which different commentators found and emphasized the aspect most important to them, whether “democracy,” “revolution,” “fascism,” “antifascism,” “communism,” “anticommunism,” “defeat of clerical reaction” or “defense of Western civilization.” The Spanish conflict became a kind of “do it yourself” kit. To a certain extent, at least, each of these differing perceptions could be demonstrated to be partially—but no more than partially—correct.

The root cause of the Civil War was the revolutionary process of the Second Republic, inaugurated five years earlier in 1931. Though every political ideology of contemporary Europe was in play in Spain, the two basic alternatives under the Republic were whether the new regime was to be a constitutional democracy or give way to a violent mass revolution. After the failure of multiple armed revolutionary insurrections, adoption of the “evolutionary” fascist approach of forming a coalition and exploiting the system enabled the revolutionaries to gain dominance by 1936, initiating the revolution under the legal cover of the Republic. Though the left’s banner was “antifascism,” paradoxically they followed the pseudo-legalist tactics of Mussolini and Hitler, not the insurrectionary tactics of Lenin or the earlier Spanish extreme left. When that became clear by July 1936, moderates and conservatives felt they had no choice but to fight back.

The era 1905-49 was a time of civil war in Europe, the biggest revolutionary civil war that in Russia from 1917 to 1921, the most widely publicized that in Spain from 1936 to 1939. No one had ever tried to treat all this as a whole, so near the end of my career I wrote a brief account, Civil War in Europe, 1905-1949 (2011).

TP: We have all read of Hitler’s intervention in the Civil War, made famous by Picasso’s painting, Guernica. But the Soviet Union also intervened. Please tell us about the role of the Soviet Union in this conflict, which you also outline in your book, The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism. How would you characterize the role played by communism in Spain from 1917 to 1939?

SP: Soviet intervention began in 1920, when Comintern representatives catalyzed organization of the Spanish Communist Party. For fifteen years this was inconsequential, Spain’s worker left being led instead by the Socialists and anarchists. In 1935, however, the Comintern switched from straight revolutionary tactics to a two-track policy, promoting the Popular Front and evolutionary politics to accompany a longer-term revolutionary strategy. This was very successful, to the extent that by the spring of 1936 Moscow was to some extent pulling back, trying to check explosive revolutionary energies from a premature outburst. Comintern policy posited a three-step long-term process: a) victory for an all-left Popular Front government, which would eliminate all centrist and rightist forces by pseudo-legal means; b) followed by formation of a Worker-Peasant government of communists and certain allies of the worker left, which would prosecute full revolution; c) followed by a final Communist regime that would consummate the process.

In the spring of 1936 Spain was the only country in Europe dominated by the illiberal, mostly revolutionary, left. Moscow saw clearly that the surest path to revolution lay in pseudo-legal evolution that avoided any complete blow-up until the left achieved total dominance of all institutions, but the extreme revolutionary left would not accept go-slow tactics. The Comintern sought to avoid civil war, which might ruin a sure thing, and its fears were justified.

When the right finally rebelled, Moscow tried to impose a politics of all-leftist “republican democracy” that averted and channeled revolution, but the anarchists and Socialists outflanked and massively outnumbered the Communists, launching the only violent mass revolution ever to occur in twentieth-century Western Europe. With Soviet assistance, Spanish Communism expanded greatly and eventually became a partially but not totally hegemonic force. Communist policy was to channel and control the revolution while concentrating on the war effort. This was by far the most rational policy adopted by any of the worker parties, but it never achieved full unity.

For the Soviet Union, the Civil War posed a great dilemma. It had been intervening in Spain politically for years, injecting considerable money into the revolutionary process, but direct military intervention was much more complicated and risky, and was harder for Moscow than for Rome and Berlin. Stalin did not decide on limited direct military intervention for two full months. He then sent much armament, but scarcely as many as 3,000 Soviet personnel ever set foot in Spain, concentrated in aviation and armor. There was never any Soviet infantry, though the Comintern organized the 35-40,000 men of the famous International Brigades (modeled on the Internatsionalisty who fought for the Bolsheviks in the Russian civil war). This was facilitated by the agreement of the irresponsible Republican government to ship most of Spain’s gold reserve (then the fourth largest in the world) to Moscow. The goal was to achieve leftist victory and also to counter the initiative of Germany, hopefully encouraging Britain and France at least indirectly to assist. By 1938 Stalin realized this was not likely to happen, and even offered to withdraw if Germany would do the same. That was impossible, so he strongly encouraged Republican resistance to the end, though the other leftist groups finally turned on the Communists, correctly accusing them of dominating their allies and falsely accusing them of abandoning the Republican cause.

The Comintern’s only success lay in gaining broad Western intelligentsia acceptance of its preferred narrative—supposed “republican democracy” against fascism, the dominant myth of the Civil War, which survives to this day.

This whole topic is one on whose study I embarked rather adventitiously. In the late 1960s Jack Greene began to direct a series for W. W. Norton on ten “Revolutions in the Modern World,” and asked me to undertake a study of the Spanish case. This intrigued me, since theretofore my two main research projects had dealt with the Spanish right. I was then a young professor at UCLA and had the advantage that two of the main collections of documents on the Spanish left were found in the Bolloten Collection at the Hoover Institution and the Southworth Collection at UC-San Diego. My resulting The Spanish Revolution (1970) attracted some attention at the time, named one of fifty “books of the year” by “Book World” of the Washington Post, but was the first of my books to be criticized by the left. The latter had received very favorably my critical treatment of two major aspects of the right, but could not tolerate the same treatment accorded the left. After more than 50 years, this now dated study still remains the only general account of the entire Spanish revolution in any language. The subject remains a virtual taboo in a field dominated by political correctness.

Thirty years later, after the Soviet archives had opened, I was able to return to this area and develop a much more authoritative and documented study, The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union and Communism (2003), which won the American Association of Slavic Studies’ Marshall Shulman Book Prize awarded for “an outstanding monograph on the international behaviour of the countries of the former Soviet bloc,” an unusual prize for a Hispanist to receive.

TP: Does the Civil War still matter for Spain?

SP: By the time of Franco’s death in 1975, a new generation of Spaniards had put the Civil War behind it. Leaders of the developed and modernized society left by Franco carried out a bloodless and peaceful transition to democratic constitutional monarchy, all national parties agreeing on complete amnesty for the past. At the same time, the history of the Civil War was researched and publicized at great length, leaving few stones unturned. There was general agreement not to employ the past in present political disputes. The Democratic Transition of 1975-79 was a remarkable civic achievement, imperfect like all human enterprises but nonetheless impressive.

In the twenty-first century, however, leftist parties in Spain have returned to their vomit, reverting to radical politics, adopting post-Marxist American-style doctrines that seek to control all culture and selectively demonize the past. Thus, the Civil War has been resurrected as a political banner and new legislation is pending to impose doctrinaire censorship and teaching content for historical discourse in Spain regarding the years 1931 to 1975. As has occurred on several earlier occasions in contemporary history, the Spanish left has adopted the most radical position on such matters to be found in any Western country.

TP: The man that emerged triumphant was Francisco Franco. Your own work on the Caudillo has been vast, to say the least. What is your view of Franco?

SP: Like all major historical figures, Franco was complicated, and he had a chameleon-like career. From the 1920s, however, he maintained three basic principles: a) loyalty to traditional Spanish Catholic culture; b) Spanish nationalism; c) preference for authoritarian government (with the exception of his relative loyalty to the Republican regime from 1931 to 1936). His dictatorship was quite liberal in its final years but Franco was never a liberal. Even in his final phase he believed that democratic government in the Western world was doomed.

TP: Has Franco been largely misunderstood or mis-characterized?

SP: Many historical figures have been demonized inaccurately, and to some extent that is true of Franco. He did not approve of the democratic Republic but did not join any of the military plots until the very last minute in July 1936, when the situation was sliding into chaos, if not worse.

Franco was a cold man and sometimes harsh, though the left somewhat exaggerates the character of his repression during and immediately after the Civil War. The revolutionaries had executed more than 50,000 people, while the rightist repression during the conflict had been equally brutal. Some months after first taking over, Franco ended summary executions but his regular military tribunals were quite punitive. The Francoist repression was no more deadly than that following other all-out revolutionary European civil wars, but that is a very low standard.

The three basic charges against Franco are accurate, namely, that a) he maintained a personal dictatorship for nearly four decades; b) politically, though never officially, he aligned himself with Hitler; and c) he presided over an extensive repression during and after the Civil War. You would not want all that on your conscience.

TP: In your book, Franco and Hitler. Spain, Germany, and World War II, you examine the balancing act that Franco undertook to thwart Hitler’s demands and Allied pressure. How did Franco manage to do that successfully?

SP: The first thing to understand is that Franco and most of his government definitely favored the Germans, convinced from 1940 to 1943 that theirs was the winning side, and this was added to gratitude for German help in the Civil War. A second thing to keep in mind is that the very early Franco regime had big ideas about expanding Spain’s role in the world, without thinking the matter through very seriously.

Franco was somewhat taken aback by the suddenness of the European war in 1939 and understood that at first Spain would have to be neutral. That changed with the fall of France in 1940, prompting great concern to profit from the German hegemony. Yet Spain was so weak after the Civil War that it would have required massive German military and economic assistance. Hitler literally could not afford that, and was particularly resistant to Franco’s insistence on taking over all Morocco, since that would have alienated Vichy France, at that point a German satellite. So Franco hesitated, demanding very favorable terms that were too steep to be met.

The point of inflexion came at the end of 1942, when it became clear that Germany might well not win the war. The Spanish regime had collaborated with the Reich in many policies but at that point began to draw off. Distancing was increased by the fall of Mussolini in July 1943, prompting the first limited “defascistization” of the Spanish regime the following month, a process that would slowly continue for many years. By the summer of 1944 Franco had to concede that Germany would almost inevitably lose, and began to draw nearer the Allies, who took a tougher line on Spain from May 1944. Franco was no genius here and made several basic mistakes, but avoided the direct plunge into war and successfully played off Spain’s unique geostrategic position, though the outcome for his regime was a near-run thing.

TP: Can we speak of a “Franco legacy?”

SP: Franco had three goals: to create a new, enduring political system; to revive neotraditional Spanish Catholic culture and to create a strong, prosperous, economically developed Spain. In the first enterprise he failed completely. The second succeeded for twenty-years, then began to fall apart. His legacy is the transformation of the Spanish economy, which largely took place under his rule. This fact greatly annoys the Spanish left, who continue to insist that this was a mere mirage, and that Spanish society failed to advance until after Franco died. This effort to extend Civil War propaganda nearly four centuries is contradicted by all the evidence

TP: You have also written about Basque nationalism. Could you tell us a little about nationalism in general, and then in the context of the Basque country?

SP: Nationalism has been the most dominant “political religion” of modern times, even more than socialism, but has taken many different forms. It is variably based on different combinations of history, ethnicity, political doctrine and language. Though it purports to be “natural,” it is a modern creation of varying combinations of these things. Whereas patriotism is often defensive and may be conservative, nationalism usually involves a project and is change-oriented. It was the dominant revolutionary force of the nineteenth century, and may be so again.

The three Basque provinces have formed part of the Spanish political system for more than a millennium, but Basque nationalism is a typically modern creation that was only invented at the close of the nineteenth century. It stemmed partly from the trauma of modernization in a conservative Catholic society with a strong sense of local identity, compounded by the dissolution of traditional structures.

The Basque provinces long enjoyed a series of provincial rights or fueros, but these had been greatly diminished. Their language consisted of a multiplicity of varying dialects which were disappearing, since most people spoke Spanish. Under the trauma of rapid modernization, regional identity or pride eventually morphed into a radical modern nationalism, partly in response to the general political crises of twentieth-century Spain.

Basque Catholicism began as traditionally ultra-Catholic, yet rapid secularization after 1960 encouraged rapid transformation. This produced an increasingly secular nationalism that took the form of a radical new messianism whose nationalist “martyrs” functioned as redemptive victims. Creation of a broadly autonomous Basque state within Spain did not satisfy but only exacerbated nationalism, which generated a massive wave of terrorism, though that has finally subsided. The latest success of nationalism has been politically to take over much of neighboring Navarre.

TP: Your book, A History of Spain and Portugal, is a comprehensive work of national history. Is there a characteristic relationship between these two countries that we must bear in mind?

SP: Portugal began as part of the kingdom of Leon-Castile, with parallel institutions, and these historical parallels have persisted, though with very distinct national personalities and cultures. Yet until recently, Portugal and Spain often excelled at avoiding and ignoring each other, despite proximity and similarities. Portugal is much smaller and much less complicated, and also less conflictive. It developed a very distinctive personality, yet, mutatis mutandis, the two countries have gone through parallel crises and developments throughout their histories.

TP: Does national history still matter?

SP: Yes, national history still matters, for countries nowadays continue to function primarily as national units, despite the European Union and contemporary globalization. Spanish historiography, for example, remains largely self-absorbed and strongly national, and that is true of most countries.

TP: Are there other projects that you are researching?

SP: Sixty-five years of major projects and book-writing did it for me. I no longer have the strength or energy for significant new projects.

TP: Any words of advice for younger scholars doing history today?

SP: The outlook is grim. Any young scholar interested in a career in history must undertake a sober assessment of the costs and stresses of trying to develop a professional life in the current environment of highly politicized institutions and an increasingly coercive culture. Employment prospects for the independent-minded scholar are meager. If I were young, I doubt that I would be able to get a job in most American universities nowadays.

TP: Professor Payne, thank you so much for the generosity of your time. It has been a great pleasure speaking with you.

The featured image shows, “The Muse Clio [the Muse of History],” by Pierre Mignard; painted in 1689.