Viktor Nikolayevich Zemskov (1946—2015), the eminent Russia historian, carried out pivotal and decisive archival research, often in fonds that were previously closed to researchers, for over a decade (1980s to 1990s). He focused on the history of political repression in the USSR, the statistics of Gulag prisoners, the fate of those repatriated after the Second World War, the Soviet working class, and military history of Russia. In the process, he answered a grim but crucial question—how many people did Stalin really kill?

In the West, the Great Purge, or the Great Terror has acquired mythic dimensions (thanks to Solzhenitsyn), in which millions are said to have perished. But the meticulous, cool-headed work of Professor Zemskov uncovered a different—and surprising—reality: from 1930 to 1953, a total of 786,000 people were “purged.”

We are able to bring you Professor Zemskov’s foundational article on Soviet repression, which he published in 1995, in Sotsiologicheskiye issledovaniya (Sociological Research), No. 9. His work continues to be ignored in the West, perhaps because it denies the various Cold War myths about Russia. This article appears through the kind courtesy of Sotsiologicheskiye issledovaniya.

Human life is priceless. The murder of innocent people cannot be justified—whether it is one person or millions. But the researcher cannot limit himself to moral evaluation of historical events and phenomena. His duty is to resurrect the true image of our past. All the more so when certain aspects of it become the object of political speculation. All this fully applies to the problem of statistics (scale) of political repressions in the USSR. This article attempts to deal objectively with this acute and painful issue.

By the end of the 1980s, historical science was faced with an urgent need for access to the secret fonds of the security agencies (former and present), since the literature and radio and television constantly mentioned various estimated, virtual figures of repressions, which were not confirmed by anything, and which we, professional historians, could not introduce into the scientific discourse without appropriate documentary confirmation.

In the second half of the 1980s, a somewhat paradoxical situation emerged for a while, when the lifting of the ban on the publication of works and materials on this topic was combined with the traditional lack of a source base, since the relevant archival fonds were still closed to researchers. In terms of style and tone, the bulk of publications from Gorbachev’s “perestroika” period (and later, too) were, as a rule, sharply expositional in nature, being in line with the anti-Stalinist propaganda campaign launched at that time (we are referring primarily to the numerous journalistic articles and notes in newspapers, Ogonyok magazine, etc.). The scarcity of concrete-historical material in these publications was more than compensated for by repeatedly exaggerated “homemade statistics” of the victims of repression, which amazed the readership with their gigantism.

In early 1989, by decision of the Presidium of the USSR Academy of Sciences, a commission of the History Department of the USSR Academy of Sciences, headed by corresponding member of the Academy of Sciences Yuri A. Polyakov, was established to determine population losses. As a member of this commission, we were among the first historians to gain access to the statistical reports of the OGPU–NKVD–MVD–MGB, the highest bodies of state power and state administration of the USSR, which had not been given to researchers before, and which were in special storage in the Central State Archive of the October Revolution (TsGaOR USSR), now renamed the State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF).

The Commission of the History Department was active in the late 1980s and early 1990s; and even then we published a series of articles on the statistics of repressions, prisoners, special settlers, displaced persons, etc. We continued this work in the years that followed, right up to the present time.

The Commission of the History Department was active in the late 1980s and early 1990s; and even then we published a series of articles on the statistics of repressions, prisoners, special settlers, displaced persons, etc. We continued this work in the years that followed and up to the present time.

As early as the beginning of 1954, the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs drew up a certificate addressed to Nikita S. Khrushchev on the number of those convicted for counter-revolutionary crimes, i.e., under Article 58 of the Criminal Code of the RSFSR and under the corresponding articles of the Criminal Codes of other Union republics, for the period 1921-1953. (The document was signed by three persons—the USSR Prosecutor, General Roman A. Rudenko, the USSR Minister of Internal Affairs, Sergei N. Kruglov, and the USSR Minister of Justice, Konstantin P. Gorshenin).

The document stated that, according to the data available in the USSR Interior Ministry, for the period from 1921 to the present, that is, until the beginning of 1954, 3,777,380 people had been convicted of counter-revolutionary crimes by the OGPU Collegium, NKVD troikas, Special Consultation, Military Collegium, courts and military tribunals, including 642,980 to capital punishment (see, State Archive of the Russian Federation, Ф. 9401. Op. 2. Д. 450).

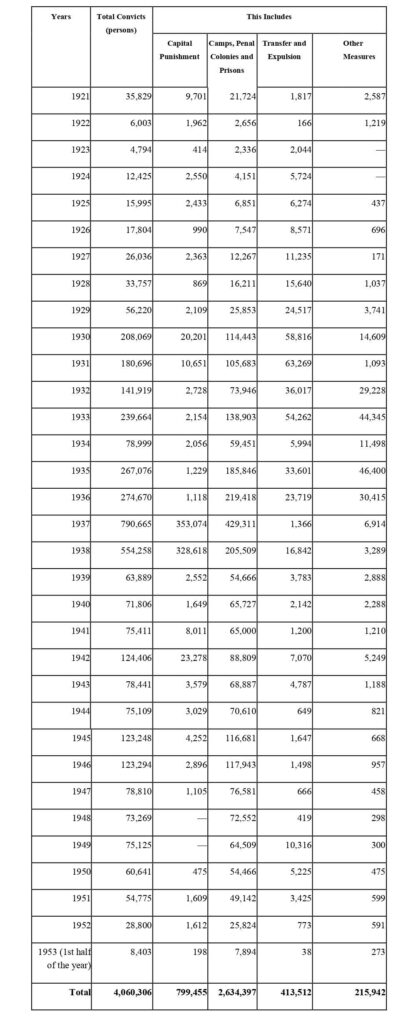

At the end of 1953, the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs prepared another report. Based on statistical reports of the 1st Special Department of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs. It gave the number of those convicted for counter-revolutionary and other particularly dangerous state crimes for the period from January 1, 1921 to July 1, 1953—4,060,306 people (on January 5, 1954, a letter signed by Sergei N. Kruglov, with the content of this information, was sent to Georgy M. Malenkov and Nikita S. Khrushchev).

This figure consisted of 3,777,380 convicted for counter-revolutionary crimes and 282,926 for other especially dangerous state crimes. The latter were convicted not under Article 58, but under other articles equivalent to it, primarily, under paragraphs 2 and 3 of Article 59 (especially dangerous banditry) and Article 193-24 (military espionage). For example, some Basmachi were convicted not under Article 58, but under Article 59. (See Table 1):

Table 1: Number of Persons Convicted of Counter-Revolutionary and other Particularly Dangerous State Crimes in 1921-1953

Note: Between June 1947 and January 1950, the death penalty was abolished in the USSR. This explains the absence of death sentences in 1948-1949. Other penalties included credit for time in custody, compulsory treatment and expulsion abroad.

It should be borne in mind that the terms “arrested” and “convicted” are not identical. The total number of convicted persons does not include those arrested who, during the preliminary investigation, i.e., before conviction, died, fled or were released.

This information was a state secret in the USSR until the late 1980s. For the first time the true statistics of those convicted for counter-revolutionary crimes (3,777,380 for 1921-1953) was published in September 1989, in an article by Vladimir F. Nekrasov in Komsomolskaya Pravda. Then this information was presented in more detail, in articles by Aleksandr N. Dugin (in the newspaper, Na boyevom postu, December 1989), Viktor N. Zemskov and D. N. Nokhotovich (Argumenty i Fakty, February 1990), in other publications by Viktor N. Zemskov and Aleksandr N. Dugin. The number of those convicted for counter-revolutionary and other particularly dangerous state crimes (4,060,306 for 1921-1953) was first publicized in 1990, in an article by Aleksandr N. Yakovlev, a member of the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee, in the newspaper Izvestya. In more detail, these statistics (1st Special Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs), with trends by years, was published in 1992 by V. P. Popov in the journal, Otechestvennyye arkhivy,

We specifically draw attention to these publications, because they contain the true statistics of political repressions. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, they were, figuratively speaking, a drop in the ocean, compared to numerous publications of another kind, which gave unreliable figures, usually exaggerated many times.

The public reaction to the publication of authentic statistics of political repressions was mixed. It was often suggested that it was fake. The journalist Anto V. Antonov-Ovseenko, emphasizing that these documents were signed by such vested individuals as Rudenko, Kruglov and Gorshenin, insinuated to the readers of the Literaturnaya gazeta in 1991: “The disinformation service was at its best at all times. Under Khrushchev, too… So, in 32 years—less than four million. It is clear who needs such criminal certificates” (A.V. Antonov-Ovseenko, “Protivostoyaniye,” Literaturnaya gazeta, April 3, 1991, p. 3). Despite Antonov-Ovseenko’s confidence that these statistics were disinformation, we will allow ourselves the courage to assert that he is wrong. These are genuine statistics, compiled by totaling, for the years 1921-1953, the relevant data available in the 1st Special Department. This special department, which at different times was part of the structure of the OGPU, NKVD, MGB (since 1953 and up to now, the Ministry of Internal Affairs), was engaged in collecting complete information on the number of those convicted on political grounds from all judicial and non-judicial bodies. The 1st Special Department was not a body for disinformation, but for comprehensive objective information collection.

After Antonov-Ovseenko, another journalist, Lev E. Razgon, sharply criticized us in 1992 (L.E. Razgon, “Lozh’ pod vidom statistiki: Ob odnoy publikatsii,” in the journal, Sotsiologicheskiye issledovaniya, (8)1992, pp., 13-14). The essence of Antonov-Ovseenko’s and Razgon’s accusations boiled down to the fact that Viktor N. Zemskov was engaged in falsification, operating with fabricated statistics, and that the documents he used were unreliable and even false. Moreover, Razgon insinuated that Zemskov was involved in the production of these false documents. At the same time, they failed to back up such accusations with any convincing evidence. My responses to Antonov-Ovseenko’s and Razgon’s criticism of us were published in 1991-1992 in the academic journals Istoriya SSSR and Sotsiologicheskiye issledovaniya (see, Istoriya SSSR, No. 5, 1991, pp. 151-152; Sotsiologicheskiye issledovaniya, No. 6, 1992, pp. 155-156).

Antonov-Ovseenko’s and Razgon’s sharp rejection of our publications based on archival documents was also triggered by their desire to “save” their “homemade statistics,” which were not supported by any documents and were nothing more than the fruit of their own fantasy. Thus, Antonov-Ovseenko published a book in English in the United States as early as 1980 called Portrait of a Tyrant, where he named the number of those arrested for political reasons only for the period 1935-1940—as 18.8 million people (see, Antonov-Ovseenko, The Time of Stalin: Portrait of a Tyranny, p. 212). Our publications, based on archival documents, directly exposed his “statistics” as pure charlatanism. Hence Antonov-Ovseenko’s and Razgon’s clumsy attempts to present the case in such a way that their “statistics” were correct, and Zemskov was allegedly a falsifier and published fabricated statistics.

Razgon attempted to contrast the archival documents with the testimonies of repressed NKVD officers with whom he interacted in detention. According to Razgon, “at the beginning of 1940, a former head of the financial department of the NKVD, who met me at one of the transit stations, when asked: ‘How many people were imprisoned?’—hesitated and answered: ‘I know that on January 1, 1939 in prisons and camps there were about 9 million living prisoners’” (“Lozh’ pod vidom statistiki: Ob odnoy publikatsii,” in the journal, Sotsiologicheskiye issledovaniya, No. 8, 1992, p. 14). We, professional historians, know very well how doubtful such information is and how dangerous it is to introduce it into scientific circulation without careful checking and double-checking. A detailed study of the current and summary statistical reports of the NKVD led, as one would expect, to the refutation of this “evidence”—in fact, in early 1939, there were about 2 million prisoners in camps, penal colonies and prisons, of whom 1,317,000 were in camps (see, GARF: Ф. 9413. Оп. 1. Д. 6. Л. 7—8; Ф. 9414. Оп. 1. Д. 1154. Л. 2—4; Д. 1155. Л. 2, 20—22).

It should be noted that the total number of prisoners in all places of deprivation of liberty (camps, penal colonies, prisons) on certain dates rarely exceeded 2.5 million. Usually, it fluctuated in different periods from 1.5 million to 2.5 million. The highest number of prisoners in Soviet history was recorded as of January 1, 1950—2,760,095 people, of whom 1,416,300 were in camps, 1,145,051 were in penal colonies and 198,744 were in prisons (see, GARF: Ф. 9414. Оп. 1. Д. 330. Л. 55; Д. 1155. Л. 1—3; Д. 1190. Л. 1—34; Д. 1390. Л. 1—21; Д. 1398. Л. 1; Д. 1426. Л. 39; Д. 1427. Л. 132–133, 140–141, 177—178).

Therefore, one cannot take seriously, for example, Antonov-Ovseenko’s assertions that after the war there were 16 million prisoners in the camps and penal colonies of the Gulag (see, Antonov-Ovseenko, “Protivostoyaniye,” Literaturnaya gazeta, April 3, 1991, p. 3). It should be understood that on the date Antonov-Ovseenko has in mind (1946), there were not 16 million but 1.6 million prisoners in the camps and penal colonies of the Gulag. One really should pay attention to the point in-between the two figures.

Antonov-Ovseenko and Razgon were powerless to prevent the mass introduction of archival documents into scientific circulation, including the statistics of repressions, which they hated. This direction of historical science became firmly grounded in the documentary archival database (and not only in our country, but also abroad). In this connection, in 1999, Antonov-Ovseenko, still in the deeply erroneous belief that the statistics published by Zemskov were false, and his (Antonov-Ovseenko’s) “own statistics” being supposedly correct (in reality—monstrously perverted), again sadly stated: “The disinformation service was at its best at all times. It is alive and well nowadays. Otherwise, how to explain the ‘sensational’ discoveries of V. N. Zemskov? Unfortunately, obviously falsified (for the archive) statistics flew around many printed publications and found supporters among scientists” (A.V. Antonov-Ovseyenko, “Chernyye advokaty,” Vozrozhdeniye nadezhdy, No. 8, 1999, p. 3). This “cry of the soul” was nothing more than a cry in the wilderness, useless and hopeless (for Antonov-Ovseenko). The idea of “obviously falsified (for the archive) statistics” has long been perceived in the scholarly world as ridiculous and absurd; such assessments do not provoke any reaction other than amazement and ridicule.

This was the natural result of the battle between professionalism and dilettantism—because professionalism must win in the end. Antonov-Ovseenko’s and Razgon’s “criticism” of us was thus in the general vein of the attack of militant dilettantism, with the aim of subjugating historical science, imposing its own rules and methods of scientific (or rather, pseudoscientific) research, which from a professional point of view are completely unacceptable.

Nikita Khrushchev also contributed to the falsification of the issue of the number of prisoners, when he wrote in his memoirs: “…When Stalin died, there were up to 10 million people in the camps” (“Memuary Nikity Sergeyevicha Khrushchova,” Voprosy istorii, No. 3, 1990, p. 82). Even if we understand the term “camps” broadly, including also colonies and prisons, then even taking this into account, in early 1953 there were about 2.6 million prisoners (see, Naseleniye Rossii v XX veke: Istoricheskiye ocherki, 2001, Vol. 2, p. 183). The State Archive of the Russian Federation (GARF) keeps copies of the report of the USSR Interior Ministry leadership to Khrushchev indicating the exact number of prisoners, including at the time of Stalin’s death. Consequently, Khrushchev was well informed about the true number of prisoners and exaggerated it almost 4 times deliberately.

The publication of Roy A. Medvedev in Moskovskie Novosti (November 1988) about the statistics of the victims of Stalinism provoked a great reaction in society (see, Roy A. Medvedev, “Nash isk Stalinu,” Moskovskie Novosti, November 27, 1988). According to his calculations, during the period 1927-1953, about 40 million people were repressed, including the kulaks, deportees, those who died of starvation in 1933, and others. In 1989-1991, this figure was one of the most popular in the propaganda of Stalinist crimes and became quite firmly embedded in the mass consciousness.

In fact, such a number (40 million) is not possible even with the most expansive interpretation of the concept of “victims of repression.” In these 40 million, Medvedev included 10 million of those who were kulaks in 1929-1933 (in reality, there were about 4 million of them), almost 2 million Poles evicted in 1939-1940 (in reality—about 380,000), and in like manner for absolutely all the elements that made up this astronomical figure.

However, these 40 million soon ceased to satisfy the “growing needs” of certain political forces to denigrate the national history of the Soviet period. The “research” of American and other Western Sovietologists, according to which 50-60 million people died of terror and repression in the USSR, was used. Like Medvedev, all components of such calculations were extremely overstated; the difference of 10-20 million was explained by the fact that Medvedev started counting from 1927, while Western Sovietologists—started counting from 1917. While Medvedev stipulated in his article that repressions are not always death, that the majority of the kulaks survived, that a smaller part of those repressed in 1937-1938 were shot, etc., a number of his Western colleagues called the figure of 50-60 million people as physically exterminated and as having died as a result of terror, repressions, famine, collectivization, and so on, and the number of those who died as a result of repressions, famine, collectivization, etc., as a result of the repressions. In short, they worked hard to fulfill the demands of politicians and special interests of their countries in order to discredit in a scientific form their opponent in the “Cold War,” not hesitating to fabricate direct slander.

This, of course, does not mean that there were no researchers in foreign Sovietology who tried to study Soviet history objectively and in good faith. Major scientists, experts on Soviet history J. Arch Getty (USA), Stephen G. Wheatcroft (Australia), Robert W. Davies (England), Gabor Rittersporn (France) and some others openly criticized the research of most Sovietologists and proved that in reality the number of victims of repression, collectivization, famine, etc. in the USSR was much lower.

However, the works of these foreign scientists with their incomparably more objective assessment of the scale of repressions were silenced in our country. Only that which contained unreliable, many-times exaggerated statistics of repressions was actively introduced into the mass consciousness. And the mythical 50-60 million soon eclipsed Roy Medvedev’s 40 million in the mass consciousness.

Therefore, when the chairman of the KGB of the USSR Vladimir A. Kryuchkov, in his speeches on television, referred to the true statistics of political repressions (he repeatedly cited the data in the records of the KGB of the USSR for 1930-1953—3,778,234 convicted political prisoners, of whom 786,098 were sentenced to execution) (see, Pravda, February 14, 1990), many people literally could not believe their ears, thinking that they had misheard. In 1990, the journalist A. Milchakov shared his impression of V. A. Kryuchkov’s speech with the readers of Vechernyaya Moskva: “…And then he went on to say: thus, tens of millions are out of the question. I don’t know whether he did it consciously. But I am familiar with the latest widespread studies, which I believe, and I ask the readers of Vechernyaya Moskva once again to carefully read Alexandr I. Solzhenitsyn’s work, The Gulag Archipelago. I ask you to familiarize yourself with the studies published in Moskovsky Komsomolets by I. Vinogradov, our most famous literary scholar. He cites the figure of 50-60 million people. I would like to draw attention to the studies of American Sovietologists, which confirm this figure. And I am deeply convinced of it” (Vechernaya Moskva, April 14, 1990).

Comments, as they say, are superfluous. Distrust was shown only for documented information and immense trust for information of the opposite nature.

However, even this was not the limit of deceiving the public. In June 1991, Komsomolskaya Pravda published Solzhenitsyn’s interview with Spanish television in 1976. From it we learn the following: “Professor Kurganov indirectly calculated that from 1917 to 1959, just from the internal war of the Soviet regime against its people, i.e., from annihilation by hunger, collectivization, exile of peasants for extermination, prisons, camps, simple shootings—just from this alone we lost, together with our civil war, 66 million people… According to his calculations, we lost in the Second World War from its [the government’s] negligent, from its sloppy conduct, 44 million people! So, in total, we lost 110 million people from the socialist system!” (“Razmyshleniya po povodu dvukh grazhdanskikh voyn: Interv’yu A.I. Solzhenitsyna ispanskomu televideniyu v 1976 g,” Komsomolskaya Pravda, June 4, 1991).

With the wording “from its negligent, from its sloppy conduct” Solzhenitsyn actually equated all the human losses in the Great Patriotic War with those who died and perished as a result of collectivization and famine, which many historians and publicists include in the number of victims of political terror and repression. We are inclined to strongly distance ourselves from such an equation.

The estimate of these losses of 44 million people is, of course, extremely overstated. We are also skeptical of the recently accepted estimate of 27 million, which has been included in many textbooks, and also consider it overstated. Without taking into account the usual annual mortality of the population (as well as the decline in birth rate), we tried to establish the human losses (military and civilian), in one way or another related to the fighting. To the losses of the armed forces who died (11.5 million, including those who died in captivity), were added the losses of civilian volunteer formations (militias, partisans, etc.), Leningrad blockades, victims of the Nazi genocide in the occupied territory, killed and tortured Soviet citizens in fascist camps, etc. The final figure does not exceed 16 million people.

In the mass media from time to time, but quite regularly, statistics of political repressions based on the memoirs of Olga G. Shatunovskaya were quoted. She was a former member of the Committee for Party Control under the CPSU Central Committee, the commission to investigate the murder of Sergei M. Kirov and the political trials of the 1930s, during the time of Khrushchev. In 1990, Argumenty i Fakty published her memoirs, where she, referring to a certain document of the KGB of the USSR, later allegedly mysteriously disappeared, noted: “…From January 1, 1935 to June 22, 1941, 19,840,000 “enemies of the people” were arrested. Of these, 7 million were shot. Most of the rest died in the camps” (O.G. Shatunovskaya, “Fal’sifikatsiya,” Argumenty i Fakty, No. 22, 1990).

The motives of Shatunovskaya’s actions are not quite clear; whether she deliberately invented these figures for the purpose of revenge (she was repressed), or whether she herself became a victim of some misinformation. Shatunovskaya asserted that Khrushchev allegedly requested the certificate, which contained these sensational figures, in 1956. This is very doubtful. All the information on the statistics of political repressions was set forth in the two certificates prepared at the end of 1953 and the beginning of 1954, which we have mentioned above.

We are sure that such a document never existed. After all, the relevant question is: what prevents the political forces currently in power, no less interested, we must assume, in exposing the crimes of Stalinism, to officially confirm Shatunovskaya’s statistics with reference to a credible document? If, according to Shatunovskaya’s version, the security service prepared such a summary in 1956, what prevented it from doing the same in 1991-1993 and later? Even if the summary of 1956 was destroyed, the primary data were preserved.

Neither the Ministry of Security of the Russian Federation (MBRF, later the FSB of the Russian Federation), nor the Ministry of Internal Affairs, nor other bodies could do this for the simple reason that all the relevant information they have directly refutes Shatunovskaya’s statistics.

Shatunovskaya’s statement that “most of the rest died in the camps” (we must assume 7-10 million, if we count from her virtual almost 13 million “others”), of course, also does not correspond to the truth. Such statements can be perceived as reliable only in an environment dominated by misconceptions that tens of millions of people allegedly died and perished in the Gulag. A detailed study of statistical reports on prisoner mortality gives a different picture. In 1930-1953, about 1.8 million prisoners died in places of deprivation of liberty (camps, penal colonies and prisons), of which almost 1.2 million died in camps and over 0.6 million in colonies and prisons. These calculations are not estimates, but are based on documents. And here arises a difficult question: what is the share of those political among these 1.8 million dead prisoners (political and criminal). There is no answer to this question in the documents. It seems that political prisoners accounted for about one third, i.e., about 600,000. This conclusion is based on the fact that those convicted of criminal offenses usually accounted for about 2/3rd of the prisoners. Consequently, out of the number of those sentenced to serve their sentences in camps, penal colonies and prisons, indicated in Tables 1 and 2, approximately this number (about 600,000) did not live to be released (between 1930 and 1953).

The highest mortality rate occurred in 1942-1943—during these two years, 661,000 prisoners died in camps, penal colonies, and prisons, which was mainly a consequence of significant cuts in nutritional standards due to the extreme war situation. Later on, the mortality rate began to steadily decline and amounted in 1951-1952 to 45.3 thousand people, or 14.6 times less than in 1942-1943 (see, Naseleniye Rossii v XX veke: Istoricheskiye ocherki, 2001, Vol. 2, p. 195). At the same time, we would like to draw attention to one curious nuance: according to the data we have for 1954, among the free population of the Soviet Union, for every 1,000 people, there died an average of 8.9 people, while in the camps and colonies of the Gulag, for every 1,000 prisoners—only 6.5 people died (see, GARF: Ф. 9414. Оп. 1. Д. 2887. Л. 64).

Having documented evidence that Shatunovskaya’s statistics are unreliable, in 1991 we published the relevant refutation in the pages of the academic journal, Sotsiologicheskiye issledovaniya (see, V.N. Zemskov, “GULAG: istoriko-sotsiologicheskiy aspekt,” in Sotsiologicheskiye issledovaniya, No. 6, 1991, p. 13).

It seemed that with Shatunovskaya’s version the question was solved even then. But that was not the case. Both radio and television continued to propagandize her figures in a rather obsessive form. For example, on March 5, 1992, in the evening program, Novosti, the host, T. Komarova, broadcast to a multimillion audience about the 19,840,000 repressed, including 7 million shot in 1935-1940, as an allegedly unquestionable fact. And this was happening at a time when historical science had proved the unreliability of this information and had genuine statistics on hand.

On August 2, 1992, a briefing was held in the press center of the Ministry of Security of the Russian Federation (MBRF), at which Major General A. Krayushkin, head of the MBRF’s Department of Registration and Archival Fonds, told journalists and other invitees that during the entire period of communist rule (1918-1990) in the USSR, 3,853,900 people were convicted on charges of state crimes and some other articles of criminal legislation of similar nature, 827,995 of whom were sentenced to execution. In the terminology used at the briefing, this corresponds to the wording “for counter-revolutionary and other particularly dangerous crimes against the state.” The reaction of the mass media to this event was curious—most of the newspapers kept a sepulchral silence. To some, these figures seemed too large; to others—too small; and as a result the editorial boards of newspapers and magazines of various directions preferred not to publish this material, thus withholding from their readers socially significant information (silence, as we know, is a form of slander). We should pay tribute to the editorial board of Izvestya newspaper, which published a detailed report on the briefing with the statistics quoted there (see, V. Rudnev, “NKVD—rasstrelival, MBRF—reabilitiruyet,” in Izvestya, August 3, 1992).

It is noteworthy that the addition of information for 1918-1920 and 1954-1990, in the above-mentioned MBRF data, did not fundamentally change the statistics of political repressions for the period 1921-1953. The MBRF staff used some other source, the data of which slightly diverge from the statistics of the 1st Special Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Comparison of data from these two sources leads to a very unexpected result: according to IBRF information, in 1918-1990, 3,853,900 people were convicted on political grounds; while according to the statistics of the 1st Special Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs in 1921-1953—4,060,306 people. In our opinion, this discrepancy should be explained not by the incompleteness of the MBRF source, but by the more strict approach of the compilers of this source to the concept of “victims of political repression.” When working in the GARF with operational materials of the OGPU-NKVD, we noticed that quite often cases were submitted for consideration by the Collegium of the OGPU, the Special Conference and other bodies, of ordinary criminals who robbed factory warehouses, collective farm storerooms, etc., as political or especially dangerous state criminals.

For this reason, they were included in the statistics of the 1st Special Department as “counter-revolutionaries” and, according to present-day concepts, are “victims of political repressions” (this can be said of recidivist thieves only in mockery); while in the IBRF source they are excluded.

The problem of eliminating criminals from the total number of those convicted of counter-revolutionary and other particularly dangerous state crimes is much more serious than it may seem at first glance. If the IBRF source did screen them out, it was far from complete. In one of the certificates prepared by the 1st Special Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the USSR, in December 1953, there is a note: “Total convicted for 1921-1938—2,944,849 people, of whom 30 percent (1,062,000)—criminals” (GARF: Ф. 9401. Оп. 1. Д. 4157. Л. 202). This means that in 1921-1938 there were 1,883,000 people convicted as purely political; for the period of 1921-1953 it turns out not 4,060,000, but less than 3 million. This is, provided that in 1939-1953 there were no criminals among the convicted “counter-revolutionaries,” which is very doubtful. However, in practice there were facts when even political persons were convicted under criminal articles.

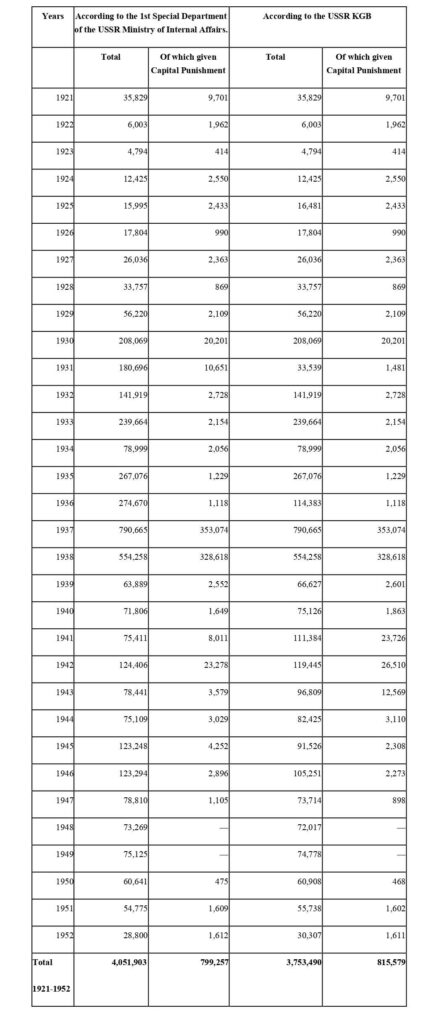

In 1997, Viktor V. Luneev published annual statistics of political convicts, taken from the source of the USSR KGB (MBRF, FSB RF) (see, V. V. Luneev, Prestupnost’ XX veka, 1997, p. 180). This made it possible to compile a comparative table of statistics of those convicted in 1921-1952 on political grounds (with the number of those sentenced to execution) according to the data of two sources—the 1st Special Department of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs and the KGB of the USSR (see Table 2). For 15 years, out of 32, the corresponding figures of these two sources coincide exactly (including 1937-1938); for the remaining 17 years, there are discrepancies, the reasons for which are yet to be clarified.

Table 2: Comparative Statistics. Convicted in 1921-1952, on Political Grounds (based on data from the 1st Special Department of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs and the USSR KGB)

The comparative statistics for the years 1921-1952 are not without some strange phenomena. Thus, according to the KGB (FSB) records for this period, the number of convicted “counter-revolutionaries” is almost 300,000 less than according to the statistics of the 1st Special Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, while the number of those sentenced to death among them is 163,000 thousand more. Of course, the main reason for this situation lies in the data for 1941, when the state security agencies took into account 23,726 people sentenced to capital punishment for political reasons, and the 1st Special Department of the NKVD—only 8011.

Two years (1937 and 1938), known as the years of the “Great Terror,” when there was a sharp rise (or jump) in the scale of political repressions, occupy a special place in these statistics. During these two years, 1,345,000 people were convicted on charges of a political nature, or 35 percent of the total number for the period 1918-1990.

The picture is even more impressive in terms of the statistics of those sentenced to death from among them. In total, for the whole Soviet period, there were 828,000 of them, of which 682,000 (or over 82 percent) fall in these two years (1937-1938). The remaining 70 years of the Soviet period accounted for a total of 146,000 death sentences on political grounds, or less than 18 percent.

Since this article is devoted to the scale, i.e., statistics of political repressions, it is not intended to investigate their causes and motivation. But we still wanted to draw attention to one circumstance, namely, the role of Stalin in this case. Recently there have been voices claiming that Stalin did not personally initiate the mass repressions, including the “Great Terror” of 1937-1938, that it was allegedly imposed on him by local party elites, etc. We should realize that this is not true.

There is a large number of documents, including published ones, which clearly show Stalin’s proactive role in repressive policy. Take, for example, his speech at the February-March Plenum of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks (b) in 1937, after which the “Great Terror” began. In this speech, Stalin said that the country was in an extremely dangerous situation due to the intrigues of saboteurs, spies, subversives, as well as those who artificially generated difficulties, thus creating a large number of the dissatisfied and irritated. This reached into the leadership cadres, who, according to Stalin, were complacent and had lost the ability to recognize the true face of the enemy.

It is quite clear to us that these statements of Stalin at the February-March Plenum of 1937 are a call for the “Great Terror,” and he, Stalin, was its main initiator and inspirer.

It is natural to want to compare the scale of political repression in the USSR with the corresponding indicators in other countries, primarily with Hitler’s Germany and Francoist Spain.

At the same time, I would like to warn against the incorrect nature of comparisons with the scale of political repression in Nazi Germany. It is claimed that the scale of repressions against German citizens in Germany was much smaller. Yes, political repressions against ethnic Germans seem relatively low, although we are talking about tens of thousands of people. But in this case we cannot stay confined in the framework of individual states, and we should put the question in a different way: what did Hitler’s regime bring to humanity? And it turns out that it is the Holocaust with six million victims and a long series of humanitarian crimes with many victims numbering many millions against the Russian, Belarusian, Ukrainian, Polish, Serbian and other peoples.

Or another example—a comparison with the scale of political repression in Francoist Spain. Now, in the USSR there were over 800,000 death sentences for political reasons. In Spain under Franco—over 80,000, or 10 times less. Hence the conclusion is made that the scale of political terror in the USSR was immeasurably higher than in Spain. This conclusion is completely wrong, in fact; these scales were approximately the same. The lion’s share of death sentences on political grounds in Spain falls on the late 1930s—early 1940s, when the population of Spain was about 20 million people, and the population of the USSR at the beginning of the Great Patriotic War was approaching 200 million; that is, the difference in population was 10 times. Yes, in Francoist Spain there were 10 times less death sentences for political reasons than in the USSR, but the population of the country was also 10 times less; that is, in terms of per capita these indicators are the same, almost identical.

We are by no means attacking the well-known postulate that there were no politically motivated prosecutions in the United States. However, we have grounds to assert that American jurisprudence deliberately qualifies certain crimes that have a political background as purely criminal. Indeed, in the USSR, Nikolaev, the murderer of Kirov, was unambiguously a political criminal. In the United States, Lee Harvey Oswald, the assassin of President Kennedy, was no less unambiguously a criminal, although he committed a purely political murder. In the USSR, identified spies were convicted under the political Article 58, while in the U.S. such spies are criminals. With such an approach, Americans naturally have every reason to advertise themselves as a society in which there is a complete absence of persecution and conviction on political grounds.

A grandiose mystification is the well-known myth about the total (or almost total) repression in the USSR of Soviet servicemen who were Nazi prisoners of war. The mythology is built, as a rule, in the darkest and most sinister colors. This applies to various publications published in the West and to journalism in our country. In order to present the process of repatriation of Soviet prisoners of war to the USSR from Germany and other countries and its consequences in the most gruesome way possible, an extremely biased selection of facts is used, which in itself is a sophisticated method of slander. In particular, sometimes gruesome scenes of violent repatriation of personnel of collaborationist military units are relished, and the corresponding conclusions and generalizations are transferred to the bulk of prisoners of war, which is wrong in principle. Accordingly, their repatriation, which, despite all the costs, was based on the natural and moving epic of finding the homeland of many hundreds of thousands of people, forcibly deprived of it by foreign invaders, is interpreted as a direction almost to the “belly of the beast.” Moreover, the biased facts are presented in a distorted form with a given interpretation, literally imposing an absurd conclusion on the reader, as if the repatriation of Soviet prisoners of war was carried out allegedly only to repress them in the Soviet Union, and there were no other reasons for repatriation.

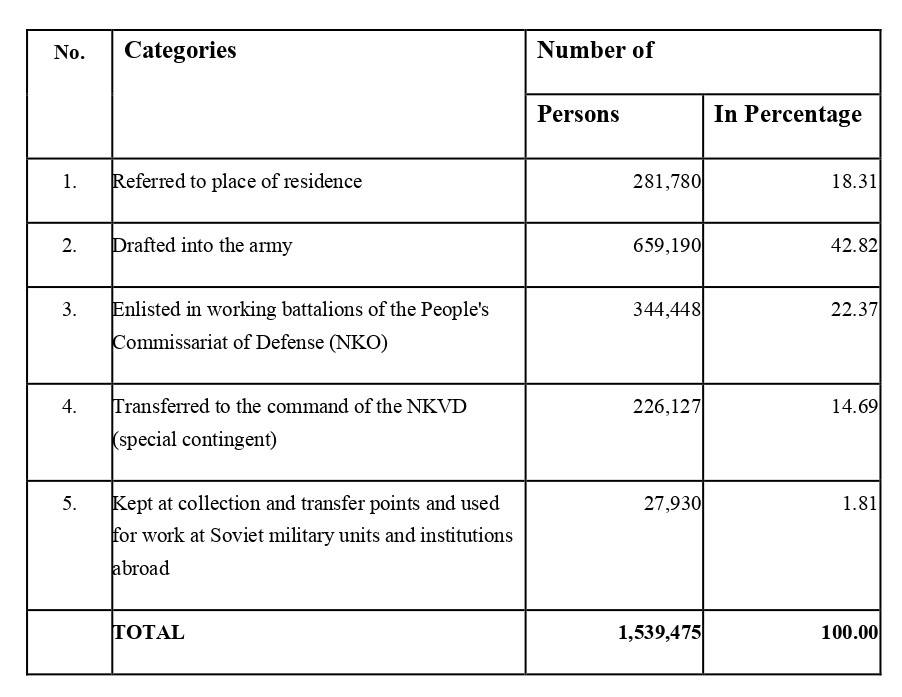

However, the data presented in Table 3 do not strongly support such pessimistic assessments. On the contrary, they shatter the myth about the alleged almost universal repression in the USSR of Soviet servicemen who had been in Nazi captivity. This statistic includes 1,539,475 prisoners of war who entered the USSR during the period from October 1944 to March 1, 1946, from Germany and other countries, of which 960,039 came from the zones of action of the Allies (West Germany, France, Italy, etc.) and 579,436 from the zones of action of the Red Army abroad (East Germany, Poland, Czechoslovakia, etc.), (see, GARF: Ф. 9526. Оп. 4а. Д. 1. Л. 62, 223—226). In 1945, 13 age-categories of servicemen were demobilized from the army, and accordingly their peers among prisoners of war (over 280,000) were released home. A part of the POWs of non-demobilizable ages were enrolled in work battalions—these were not at all repressed, but were one of the forms of mobilized labor force (a common practice at that time), and their assignment to the place of residence was made dependent on the future demobilization of their peers who continued to serve in the Red (Soviet) Army. The majority of prisoners of war of non-demobilizable ages were reinstated into military service. Only the special contingent of the NKVD remained (the share of the total number of prisoners of war was as follows—less than 15 percent); but we must not forget that the bulk of this category of repatriated prisoners of war were persons who, after their capture, had entered the military or police service of the enemy.

Table 3: Distribution of Repatriated Soviet Prisoners of War by Category (as of March 1, 1946)

The notion that the highest political leadership of the USSR allegedly equated the concepts of “prisoners” and “traitors” belongs to the category of retrospectively invented falsehoods (artifacts). Such “making up” usually pursued the goal of more slander and to discredit Stalin. In particular, the expression attributed to Stalin—”we have no prisoners, we have traitors”—is a fable (artifact), composed in 1956 in the writer-publicist environment, during the wave of criticism of the personality cult of Stalin. Actually, there are quite a lot of invented artifacts. They include, for example, the tale of Stalin’s “refusal” to exchange prisoners—Field Marshal Paulus for his son Yakov Dzhugashvili (in reality, this did not happen; it is a later fiction). Specially for the purpose of discrediting Stalin in Khrushchev’s time was fabricated the fake “report” of Soviet intelligence officer Richard Sorge, allegedly dated June 15, 1941 and which reported the date of the German invasion—June 22, 1941 (in fact, Sorge did not send such a report, because he did not know the exact date of the German attack on the USSR).

Medvedev suggests that up to 1946 inclusive, NKVD agencies repressed from 2 to 3 million people living on the territory of the USSR, which was subjected to fascist occupation (see, R.A. Medvedev, “Nash isk Stalinu,” in Moskovskiye novosti, November 27, 1988). In reality, 321,651 people were convicted on political grounds throughout the Soviet Union in 1944-1946, of whom 101,77 were sentenced to capital punishment (according to the records of the 1st Special Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs). It seems that the majority of those convicted from the former occupied territory were punished justly—for specific treasonous activities.

The statement widely used in Western Sovietology that 6-7 million peasants (mostly kulaks) perished during the collectivization of 1929-1932 does not stand up to criticism. In 1930-1931, just over 1.8 million peasants were sent into “kulak exile,” and at the beginning of 1932, 1.3 million remained there. The loss of 0.5 million was due to deaths, escapes, and the release of the “wrongly exiled.” During 1932-1940, in the “kulak exile,” 230,258 people were born, 389,521 died, 629,042 escaped and 235,120 returned after escaping. And from 1935, the birth rate began to exceed the death rate: in 1932-1934, in the “kulak exile,” were born 49,168 and 271,367 died; in 1935-1940—respectively 181,090 and 108,154 people (see, GARF: Ф. 9479. Оп. 1. Д. 89. Л. 205, 216).

There is no agreement in the scientific and journalistic literature on the question of whether or not to include the dispossessed peasants among the victims of political repressions. The kulaks were divided into three categories, and their total number varied from 3.5 million to 4 million (it is still difficult to establish the exact number). Here it should be noted immediately that the kulaks of the 1st category (arrested and convicted) are included in the statistics of political repressions given in Tables 1 and 2. The question of the 2nd category, kulaks sent under escort to live in “cold lands” (special resettlement), is disputable, where they were under the supervision of the NKVD agencies, which looked very much like political exile. As for the kulaks of the 3rd category, who avoided both arrest and conviction, and were sent to special settlement, there is no reason, in our opinion, to include them in the number of victims of political repression. In passing, we note that among the landlords whose property was expropriated in 1918, only those who were subsequently arrested and convicted by the punitive bodies of the Soviet power can be considered victims of political repression. The concepts of “expropriated” and “repressed” should not be equated.

We have studied the entire set of statistical reports of the Special Settlements Department of the NKVD-MVD of the USSR. It shows that in 1930-1940 about 2.5 million people were in “kulak exile,” of whom about 2.3 million were kulak peasants and about 200 thousand were “admixture” in the form of urban declassified element, the “dubious element” from border zones and others. During this period (1930-1940), approximately 700,000 people died there, the vast majority of them in 1930-1933 (see, V. N. Zemskov, Spetsposelentsy v SSSR. 1930—1960: Abstract of the dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Historical Sciences, Moscow, 2005, pp. 34-35). In light of this well-known and often quoted statement of Winston Churchill that in one of the conversations with him, Stalin allegedly named 10 million expelled and dead kulaks (see, Winston Churchill, The Second World War, Vol. 4, The Hinge of Fate, pp. 447-448), should be perceived as a misunderstanding.

The victims of political terror often include those who died of hunger in 1933, which is hardly legitimate. After all, we are talking about the fiscal policy of the state in the conditions of a natural disaster (drought). At that time, in the regions affected by drought (Ukraine, the North Caucasus, part of the Volga region, the Urals, Siberia, Kazakhstan), the state did not find it necessary to reduce the volume of obligatory supplies and confiscated from the peasants the meager harvest to the last grain. The polemics on the issue of the number of those who died from the famine is far from being finalized—estimates vary mainly within the range from 2 million to 8 million (see, V.P. Danilov, “”Diskussiya v zapadnoy presse o golode 1932—1933 gg. i «demograficheskaya katastrofa» 30—40-kh godov v SSSR,” in Voprosy istorii, no. 3, 1988, pp. 116-121; R. Konkvest, “Zhatva skorbi,” in Voprosy istorii, No. 4, 1990, p. 86; Naseleniye Rossii v XX veke: Istoricheskiye ocherki, Vol. 1, pp. 270-271). According to our estimates, the victims of the Holodomor of 1932-1933 were about 3 million people, about half of them in Ukraine. Our conclusion, of course, is not original, since approximately the same estimates were given by historians V.P. Danilov (USSR), S. Wheatcroft (Australia) and others back in the 80s of the XX century (see, V.P. Danilov, “Kollektivizatsiya: kak eto bylo,” in Stranitsy istorii sovetskogo obshchestva: fakty, problemy, lyudi, Moscow, 1989, p. 250).

The main obstacle to the inclusion of those who died from the famine in 1933 among the victims of political terror with the formulation developed in human rights organizations of “artificially organized famine with the purpose of causing mass death of people” is the fact that the fiscal policy was a secondary factor, and the primary factor was a natural disaster (drought). Nor was it intended to cause mass deaths (the political leadership of the USSR did not foresee and did not expect such negative consequences of its fiscal policy in conditions of drought).

In recent years, the idea has been actively promoted in Ukraine (including in scientific circles) that the famine of 1932-1933 was the result of Moscow’s anti-Ukrainian policy, that it was a deliberate genocide against Ukrainians, etc. the population of the North Caucasus, the Volga region, Kazakhstan and other areas where there was a famine. There was no selective anti-Russian, anti-Ukrainian, anti-Kazakh or any other orientation here. In fact, the United Nations was guided by the same considerations, which in 2008 refused to recognize the fact of the genocide of the Ukrainian people by a majority vote (although the United States and England voted for such recognition, they were in the minority).

The losses of the peoples deported in 1941-1944—Germans, Kalmyks, Chechens, Ingush, Karachais, Balkars, Crimean Tatars, etc.—are also greatly exaggerated. In the press, for example, there were estimates that up to 40 percent of Crimean Tatars died during transportation to the places of expulsion. Whereas the documents show that out of 151,720 Crimean Tatars sent in May 1944 to the Uzbek SSR, 151,529 were accepted by the NKVD of Uzbekistan, and 191 people (0.13%) died on the way (see, GARF: Ф. 9479. Оп. 1. Д. 179. Л. 241—242).

It is another matter that in the first years of life in the special settlement, in the process of painful adaptation, the mortality rate significantly exceeded the birth rate From the moment of the initial settlement until October 1, 1948—25,792 were born and 45,275 died among the evicted Germans (excluding the labor army); among the North Caucasians (Chechens, Ingush, Karachays, Balkars, etc.)— respectively 28,120 and 146,892; among the Crimeans (Tatars, Armenians, Bulgarians, Greeks)—6,564 and 44,887; among those deported in 1944 from Georgia (Meskhetian Turks, etc.)—2,873 and 15,432; among Kalmyks—2,702 and 16,594 people. Since 1949, among all of them, the birth rate became higher than the death rate (see, GARF: Д. 436. Л. 14, 26, 65—67).

History dilettantes include all human losses during the Russian Civil War among the unconditional “victims of the Bolshevik regime.” From the fall of 1917 to the beginning of 1922, the population of the country decreased by 12,741,300 people (see, T.A. Polyakov, Sovetskaya strana posle okonchaniya Grazhdanskoy voyny: territoriya i naseleniye, Moscow, 1986, pp. 98, 118); this also includes White emigration, the number of which is not precisely known (approximately 1.5 to 2 million). Only one warring party (the Red) is declared the culprit of the Civil War, and all the victims, including its own, are attributed to it. How many “exposé” materials have been published in recent years about the “sealed train,” the “intrigues of the Bolsheviks,” etc.?! It is impossible to count. It has often been claimed that if it had not been for Lenin, Trotsky, and other Bolshevik leaders, there would have been no revolution, no Red Movement, and no Civil War (we should add, with the same “success” one can claim that if it had not been for Denikin, Kolchak, Yudenich, and Wrangel, there would have been no White Movement). The absurdity of such assertions is quite obvious. The most powerful social upheaval in world history, such as the events of 1917-1920 in Russia, was predetermined by the entire previous course of history and was caused by a complex set of intractable social, class, national, regional and other tensions. In light of this, science cannot broadly interpret the concept of “victims of political repression” and includes in it only persons arrested and convicted by the punitive bodies of the Soviet power for political reasons. This means that the victims of political repressions are not the millions who died of typhus, typhoid, typhoid fever and other diseases. Nor are the millions of people who died on the fronts of the Civil War on all opposing sides, who died of hunger, cold, etc., the victims of political repression.

And as a result, it turns out that the victims of political repressions (during the years of “Red Terror”) are not counted in millions at all. The most we can talk about is tens of thousands. It is not without reason that when at the briefing in the press center of the IBRF on August 2, 1992, the number of those convicted on political grounds since 1917 was named, it did not fundamentally affect the corresponding statistics, if we count from the year 1921.

According to the available records in the FSB RF, in 1918-1920, 62,231 people were sentenced for “counter-revolutionary crime,” including 25,709 for execution (see, V. V. Luneev, Prestupnost’ XX veka, 1997, p. 180; V.N. Kudryavtsev, A.I. Trusov, Politicheskaya yustitsiya v SSSR, Moscow, 2000, p. 314). This information is part of the statistics above, mentioned at the briefing, at the press center of the IBRF, on August 2, 1992. We believe that the above statistics for the period of the Civil War are incomplete. Many victims of lynchings of “counter-revolutionaries” are probably not taken into account. These lynchings were often not documented at all, and the FSB has clearly taken into account only the number that is confirmed by documents. It is also doubtful that in 1918-1920 Moscow received exhaustive information about the number of the repressed from localities. But even taking all this into consideration, we believe that the total number of repressed “counter-revolutionaries” (including victims of the “Red Terror”) in 1918-1920 hardly exceeded 100,000 people.

Our publications with the statistics of political repressions, Gulag prisoners, and “kulak exile,” based on archival documents, had a significant impact on Western Sovietology, forcing it to abandon its main thesis about the alleged 50-60 million victims of the Soviet regime. Western Sovietologists cannot simply dismiss published archival statistics as an annoying fly and are forced to take them into account. In the Black Book of Communism, written in the late 1990s by French specialists, this figure is reduced to 20 million (see, The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, 1999, p. 4).

But even this “reduced” figure (20 million) we cannot recognize as acceptable. It includes both a number of reliable data, confirmed by archival documents, and estimated figures (many millions) of demographic losses in the Civil War, those who died of hunger in different periods, etc. The authors of The Black Book of Communism even included in the number of victims of political terror those who died of starvation in 1921-1922 (famine in the Volga region, caused by a severe drought), which neither Medvedev nor many other experts in this field had never done before.

Nevertheless, the very fact that the estimated scale of victims of the Soviet regime has decreased (from 50-60 million to 20 million) indicates that during the 1990s, Western Sovietology underwent a significant evolution towards common sense, but, however, got stuck halfway through this positive process.

According to our calculations, strictly based on the documents, it turns out to be no more than 2.6 million, with a rather extended interpretation of the concept of “victims of political terror and repression.” This number includes more than 800,000 sentenced to capital punishment on political grounds, about 600,000 political prisoners who died in places of deprivation of liberty, and about 1.2 million who died in places of expulsion (including “kulak exile”), as well as during transportation there (deported peoples, etc.). The components of our calculations correspond readily to four criteria specified in The Black Book of Communism in defining the concept of “victims of political terror and repression,” namely: “shooting, hanging, drowning, beating to death;” “deportation—death during transportation;” “death in places of expulsion;” “death as a result of forced labor (exhausting labor, disease, malnutrition, cold)” (Black Book, p. 4).

As a result, we have four main variants of the scale of victims (executed and killed by other means) of political terror and repression in the USSR: 110 million (Solzhenitsyn); 50-60 million (Western Sovietology during the Cold War); 20 million (Western Sovietology in the post-Soviet period); 2.6 million (our document-based calculations).

The question may arise—where is Roy Medvedev’s 40 million? This figure is not comparable with the above figures; there we are talking only about those executed and killed by other means, while Medvedev’s statistics also includes millions of people who, although subjected to various repressions, remained alive. This, however, does not cancel out the fact that Medvedev’s statistics are still exaggerated many times over.

In the serious scientific literature of the modern period, authors avoid making frivolous statements about the allegedly many tens of millions of victims of Bolshevism and the Soviet regime. In light of this, the book by Yuri L. Dyakov, Ideologiya bol’shevizma i real’nyy sotsializm—The Ideology of Bolshevism and Real Socialism (2009), in which, in the list of crimes of the CPSU, there is also mentioned “the destruction of tens of millions of its people” (p. 146), is in sharp contrast. Moreover, Dyakov considers the so-called “calculations” of Professor Ivan A. Kurganov (which in his time were accepted by Solzhenitsyn) to be quite reliable, according to which, due to the fault of Bolshevism, the population losses in Russia (USSR) in 1918-1958 amounted to more than 110 million people (p. 234). The position of Dyakov in his book rests on the complete disregard of the whole complex of available historical sources. The use of documentarily refuted statistics by Dyakov, on the basis of which he draws far-reaching conclusions and generalizations on the topic under study, cannot be called other than a pathological deviation from the mainstream in this area of historical science.

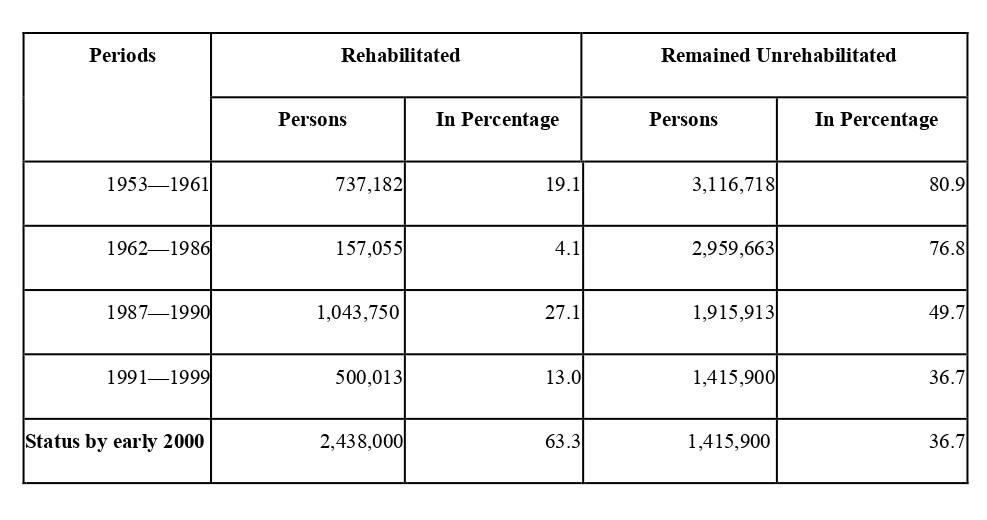

And the last issue we would like to highlight is the statistics of rehabilitation and its stages. Let us return to our basic figure—3,854,000 (more precisely—3,853,900) convicted on political grounds for all 73 years of Soviet power. This figure was used to calculate the number and proportion of those rehabilitated.

Rehabilitations took place during Stalin’s lifetime, but their scale was quite insignificant. The period of mass rehabilitation began in 1953, immediately after the famous events associated with the death of Stalin, the arrest and execution of Beria, and especially after the 20th Congress of the CPSU in 1956, which condemned the cult of personality of Stalin.

The rehabilitation was led by the former Stalinist entourage headed by Khrushchev, directly involved in the former Stalinist repressions. In this case, they, especially Khrushchev, showed a well-known political foresight. In the first years after Stalin’s death, the situation was such that to continue the line of the late leader without significant adjustments—was a path of deliberate political suicide. The idea of mass rehabilitation for many reasons was politically advantageous and was literally necessary. The fact that this process was initiated and led by Stalin’s former entourage, which was directly involved in the repressions, we can formulate their internal motivations as follows: “It is better that we do it, rather than someone else does it instead of us.” The instinct of political self-preservation worked here.

The rehabilitation process had its ups and downs over time. Its first stage—the mass “Khrushchev’s” rehabilitation—covers the period 1953-1961. Then rehabilitation declined, but nevertheless continued (at a slower pace). Since 1987, the mass “Gorbachev’s” rehabilitation began, which significantly surpassed the “Khrushchev’s” rehabilitation. The number and proportion of the rehabilitated (and unrehabilitated) are presented in Table 4.

Table 4: The Rehabilitation Process, from 1953 to 1999

The term “innocently convicted” does not apply to all those rehabilitated. Indeed, hundreds of thousands were victims of entirely far-fetched and fabricated charges. But there were also many who had done concrete actions (including those of an armed nature) against the existing system. They were rehabilitated on the grounds that their struggle against Bolshevism and Soviet power was allegedly “just.” In particular, in the mid-1990s, under this politically biased and legally questionable thesis, practically all participants in the numerous kulak-peasant uprisings and rebellions of the period 1918-1933 were rehabilitated (and everyone was rehabilitated, including executioners who shot and hanged communists, Komsomol members and non-party Soviet activists).

It even came to the point that in 1996, SS Gruppenführer Helmuth von Pannwitz was rehabilitated by the decision of the Chief Military Prosecutor’s Office. Cossack units under the command of Pannwitz—the 1st Cossack Cavalry Division, then deployed in the 15th Cossack Cavalry Corps—participated in punitive operations in Yugoslavia. In 1947, together with other war criminals, he was hanged by sentence of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR. However, in 2001 the Military Prosecutor’s office of the Russian Federation made a different conclusion: von Pannwitz was justifiably convicted for his criminal acts and cannot be rehabilitated.

Table 4 shows that out of almost 3,854,000 convicted on political grounds (according to the personalized record available in the Federal Security Service of the Russian Federation) by the beginning of 2000, 2,438,000 (63.3 percent) were rehabilitated and about 1,416,000 (36.7 percent) remained unrehabilitated.

Later on, the rehabilitation process stalled, because, in fact, there was no one to rehabilitate. The bulk of the unrehabilitated were accomplices of the fascist occupiers—all those Polizei, the Karateli [death squads], Sonderkommando bosses, Vlasovites, etc., etc., who, as a rule, were held under Article 58 as political criminals. There was a provision in Soviet legislation that prohibited the rehabilitation of accomplices of the Nazi occupiers. This provision has passed into the current Russian legislation, i.e., their rehabilitation is expressly prohibited by law. In addition to accomplices of the Nazi occupiers, a number of other persons remain unrehabilitated, whose actions were of such a nature that it is simply impossible to rehabilitate them.

Such are the complex pages of national history, if we do not fantasize, but rely on the facts reflected in the documents.

To answer the question about the impact of repressions in their real scale on Soviet society, we would suggest familiarizing ourselves with the conclusions of the American historian Robert Thurston, who in the mid-1990s published a scientific monograph Life and Terror in Stalin’s Russia, 1934-1941 (1996). The main conclusions, according to Thurston, are as follows:

- The Stalinist terror system as described by previous generations of Western researchers never existed; the impact of terror on Soviet society in the Stalin years was not significant;

- There was no mass fear of repression in the Soviet Union in the 1930s;

- Repression was limited and did not affect the majority of the Soviet people;

- Soviet society supported the Stalinist regime rather than feared it;

- The Stalinist system provided the majority of people with the opportunity to live in the Soviet Union

These conclusions of Thurston, which are almost blasphemous from the perspective of the traditions and spirit of Western Sovietology and as perceived by the majority of Sovietologists, are based on documented facts and statistics. In addition, Thurston, not being a supporter of communism and Soviet power, nevertheless in his endeavor to get to the historical truth managed to be detached from the established anti-communist and anti-Soviet stereotypes and dogmas. This is, figuratively speaking, a ray of light in a dark realm.

N

Featured: Still Life, by Yuri Neprintsev; painted in 1979.