The following points were the lead into the Daily Mail’s story on January 26 2021 about the findings of Edelman’s 2021 Trust Barometer:

- New data from Edelman shows that American trust in media is at all-time low

- 56% believe that journalists and reporters are purposely trying to mislead

- 58% think news organizations are more interested in ideology than facts

- Only 18% of Republicans trust the media versus 57% of Democrats

- As a whole, 46% of Americans of all political stripes say they trust the media

- Media trust is at lows around the world indicating a global phenomenon

In the United States this figure is more or less on par with the percentage of the population that believed that the outcome of the 2020 USA election was the result of foul play. While journalists may be disappointed by this lack of trust, given that from the moment of Donald Trump’s election victory in 2016, they shifted from opposing his candidature to all-out war with him and those who did not represent their interests or view of the world, one can only ask: why would they be surprised?

If the journalists were to be believed, then Trump had not only colluded with Russia to win the White House in 2016, he and his followers were white supremacists. His racism was such that he banned Muslim immigrants for merely being Muslim immigrants, and was happy to put Latino migrant children in cages because they were Latino migrant children. Who could not see that he was a monster? Then there was his sheer incompetence—his handling of COVID directly led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people. Who could not see that he was a complete idiot? Surely, it was utterly immoral to let the fate of the world hang upon his deranged and deplorable supporters having the numbers on election day.

And so it was, as an intrepid reporter for Time magazine on February 4th, informed the world, in a sentence that would be endlessly repeated by conservative bloggers and Youtubers who were not allowed to say that the 2020 election had been rigged: “a well-funded cabal of powerful people, ranging across industries and ideologies, working together behind the scenes to influence perceptions, change rules and laws, steer media coverage and control the flow of information.”

As the author of the piece, Molly Ball, spun it, thanks to their tireless efforts in making it easier to vote, democracy was saved from a tyrant. Other journalists had been routinely comparing the tyrannical Trump to Hitler, so she did not need to repeat that historical analogy; though the historian Timothy Snyder, who knows a thing or two about the holocaust, had said early on in the Trump presidency that the comparisons with Hitler might be a little overblown—Mussolini was closer to the mark.

To the Trump haters who appeal, when it suits them, to “the science,” who “fact check” every joke or exaggeration that Trump has ever made, and who see the need for a Reality Czar to deprogram the members of the Trump cult, the minor fact that Trump had not imprisoned any journalists, or any other of his political opponents for that matter, was of no consequence. As for the dribbling deranged deplorables—likened by the actor Sean Penn and FBI Director James Comey to members of Al Qaeda—who, on election night, thought that their votes might just have been discounted or put in the Biden pile along with the votes of convicted felons, illegal aliens, people of no fixed address, the dead, and the never having existed, Big Tech joined the forces of older media in censoring and denouncing them.

The whole idea that this “cabal” was a “cabal” rigging the vote was a conspiracy theory spread by QAnon. Given that the sibylline utterances of Q were bat-crap crazy and that nothing Q had ever predicted actually occurred, the identity of Q came down to one possibility—Q was someone who was dedicated to making Trump and all of his supporters look like idiots. That left the following possibilities about who came up with Q: either someone having a laugh at the expense of the small band of deplorables with unlimited gullibility, or a Democrat, or a never-Trump shill.

It may well be that the reason so few journalists had so little interest in genuinely investigating why half the United States did not think like they were supposed to think was sheer laziness—for finding them would mean going and talking to people beyond the bars, clubs and restaurants frequented by journalists from New York, Washington, Portland, Los Angeles, or San Francisco. It would have required journalists going to very unpleasant places and hanging out with a bunch of weirdos and white supremacists—yuk!

Given the way the word “racists” was thrown around so frequently as the answer to the question, who actually voted for Trump, it is only reasonable to think that if laziness were in the mix it was ideologically induced laziness. The same question arises about Q. Is it because of laziness that none of those intrepid reporters, who turned up to all those press conferences to give Trump a good piece of their mind, were interested in finding out who Q was? Or, was Q an ideological gift that just kept on giving, something that only completely came to the fore after the election, when anyone who called for an election audit was said to be just repeating that crazy election conspiracy theory invented by Q?

In a world where an ideological trope—racism, sexism, Islamophobia, transphobia et al.—explains all the great social and political problems of the day, and hence is ever ready at hand to tie a story together, it all made sense that if people were crazy enough to support Trump they must be crazy enough to believe in Q; and hence if they are crazy enough to support anything Q says then they are crazy, though even if they have never heard of Q, they are still stooges of Q, who is a stooge of Trump, who was Putin’s stooge. And if you don’t believe that, you believe in conspiracy theories. It is a serious question: how much recreational drug use contributes to this way of thinking amongst our educated elite?

Or, to put it another way: why would the media-entertainment, sport and big tech moguls, celebrities, academics, global financiers, wall-street brokers, captains of industry, trade-union officials, journalists, and other societal and economic “leaders”—in sum, the “cabal”—who ranged from those who openly called for Trump’s assassination, to those who just wanted him beaten up, to the moderates who just wanted him impeached and banned for life from social media access or ever holding political office—tolerate Trump’s deranged supporters having their vote counted?

But lest anyone think that any of the “cabal” were thinking along such logical lines, Molly Ball (our intrepid reporter) set the record straight: “They were not rigging the election; they were fortifying it.” Yes indeed, democracy was fortified by a raft of changes to voter eligibility, the process of voting, as well as the security protocols surrounding voting. Most significant was the easing of conditions of mail-in votes, with a number of states changing early voting and voter deadlines rules, and “simplifying” or scrapping altogether requirements for authenticating voter ID and ballot signatures. All of which just happened to make it much easier for a third party to tamper with a ballot. In some states the security around voting was less than is needed to buy a beer in the USA. “Fortifying” the election would also explain the videos of the unsealed boxes of ballots being found or delivered at all those weird times, and the multiple tabulation of ballots performed in the wee small hours when scrutineers had been sent home. To such non-evidence, journalists, in unison, repeated the immortal line of that great metaphysical rationalist Chico Marx: “Well, who ya gonna believe? Me, or your own eyes?”

Let us, though, imagine for a moment that the above survey results came from the 1950s: in light of the very different values that most people in the USA shared then, would the journalists of today think such widespread mistrust in the media had been a bad thing? For the values that most journalists and other urban professional groups supported back then were pretty much the values Trump and his supporters defended in 2016, viz.,

- that citizenship was not the right of someone who entered the United States by illegal means;

- that the national partnerships, especially between labor and capital, and the national interest had to take priority over global partnerships and global capital and the economic well-being of other nations;

- that the key to the nation’s welfare was an environment in which access to employment was a major priority;

- and that citizens of the United States could and should peacefully resolve their problems rather than treat other Americans on other aspects of their being, such as, race, gender, or sexual preference.

That is, it is hard to argue that the progressive journalists of the 1950s, who generally thought that most other journalists were mere mouth pieces of America’s ruling class interests, that is, the journalists who went along with the Soviet depiction of the United States as a cauldron of racial and working-class oppression and hatred, would have been anything other than heartened to see that the population did not accept the ideological propaganda of their bourgeois colleagues.

Leaving ideology aside for a moment, one might reasonably argue then—as now—that there is something else that one might consider in more normal times, if one were seriously interested in whether people should believe what journalists tell them. And that is the question of the competence of journalists to investigate a story thoroughly. I hardly think it would be a bad thing for the majority of the population to suspect that journalists are not particularly trustworthy, because, said people recognize that journalists like most people take short cuts, and soft options, and generally are neither overly bright, nor overly industrious.

I think most of us find that if we want a good tradesman, a good doctor, a good dentist, a good lawyer, it is better to ask around than take pot-luck—because we regularly come across people in professions and trades who are not very good at what they do. Why would journalists be an exception? I doubt that most people have ever thought that journalists are naturally wiser, smarter, more industrious or less prone to error and prejudice than other people. When it comes to political reporting, it is also obvious that most political journalists think like their colleagues and people who have had a similar education to them. And they nearly all think they are entitled to set the agenda for how the world should be.

As for their education, journalists are just as likely to have been taught by people who are also not overly bright or thoughtful. By bright and thoughtful I mean someone who is not only naturally gifted, but someone who is really hungry to know stuff, someone with a wide range of interests and curiosity, someone who looks at issues from vastly different and contradictory viewpoints, someone who is not only open-minded, but who is willing to be, and who admits to being, wrong. Such a person is far better placed to identify connections and associations that others fail to notice because they are not prisoners of their own vanity, nor of a consensus, whether that consensus be disciplinary or ideological in nature.

In the fifty or so years of my life spent as a university student and university teacher, I encountered plenty of naturally gifted minds, but I met very few bright or genuinely thoughtful people who taught Humanities. Most that I met read little outside of their area of “expertise,” were far stronger in conviction than in curiosity, had not significantly changed their minds on the issues that they taught and studied since their graduate days, were prone to vanity, loved to “critique,” but hated to be criticized, and generally enjoyed being with people who thought just like them.

For most of them being a good teacher amounted to them being enthusiastic in encouraging their students to think just like them. It can hardly be expected that those who prepared to be journalists by going to college would end up being particularly bright—their chances of even getting a degree requiring that their ideas generally conform to the narratives of their teachers, just as their chances of getting a job also required a conformity of values and social and political outlook with their fellow journalists and editors.

In so far as the class (covering a range of occupations) that crafts, instructs and monitors narratives which have social and political efficacy are almost universally subject to the same norms and processes of socialization, it is not surprising that those who have gone to college and received their information from the media, believe what they read or hear and watch when it is prepared by people who think just like they do—all of which conforms to the ideas and associations that they identify with, routinely discuss, and have reaffirmed in almost every social setting.

This is no less the case in my circle of friends, most of whom have been fairly well educated, have firm political convictions (which I do not remotely share) about how to make the world a just and fair place. Most of them, like other well-educated Western peoples, receive their information from such seemingly “reliable” and professionally run outlets, such as, the New York Times, the Guardian, or (here in Australia) the Australian ABC.

I realize that I have been very fortunate in that my political teachers have been people like Thucydides, Plato, Aristotle, Tacitus, Augustine, Hobbes and such like (who mean nothing to most of my friends), rather than Rachel Maddow, Don Lemon, or the writers at BuzzFeed or Mother Jones and their Australian equivalents. But even when I am with fellow academics who are reasonably well read, when it comes to politics, many of them sound much more like Maddow and Lemon than Thucydides, et al. And I rarely meet anyone who is remotely interested in thinking what would a Thucydides have made of this event—anyway he was just another white guy.

Like most of my friends, most academics I know do not think that there has been anything wrong with the behavior of the media, or Big Tech, or universities, or schools, or publishers, or human resource officers, or celebrities, or sports administrators, or high ranking figures from intelligence agencies and the military, who have routinely denounced, “de-platformed,” silenced, sacked, harangued critics of ideas that have become part of the contemporary consensus of the class that instructs and informs the rest of us about ideas and values.

My suspicion, though, is that more than half the population—that is the people who expressed their mistrust of journalists—think that our social and political elite are rotten, and not just victims of natural human failings, such as, laziness, incompetence and arrogance. They think this because they see that there is no area of their life that the state and corporate world has not conspired (I use the word deliberately) to politicize and make subject to some authority or other that can destroy one’s reputation and livelihood. That is to say, more than half the adult population of the United States believes they are now living in an increasingly totalitarian society—and the rest of the West is not far behind. Sure, they know the difference between the USA and a country that harvests the organs of their criminals, but many would also point to the harvesting of body parts of the unborn to say, make COVID vaccines, as something equally horrifying and unimaginable a couple of generations ago.

What is not as clear is the exact moment at which all the main institutions of the nation were controlled by an elite that chose to sacrifice freedom of thought and freedom of expression for a program, which they represent as justice. What, though, can be said with certainty is that the moment was the outcome of the victory of ideas that had some, albeit very minor, support in the United States amongst intellectuals even prior to the Russian Revolution, but by the time of the 1960s had swept up a great part of the student body at its most prestigious institutions of higher learning.

By the time Alan Bloom published The Closing of the American Mind in 1987, the radical ideas of the 1960s about human emancipation, how power is constituted and how it can be transformed to achieve greater emancipation had not only changed the university curricula within the Humanities, but the entire mindscape of a generation who now typically thought in terms of identity and diversity (understood as group identity which being a fundamental characteristic to be considered when employing or judging people). Bloom had identified what had become known around the same time as political correctness within the universities. What was less obvious then was the extent to which other institutions had succumbed to the same set of bad ideas.

As someone who observed the Trump presidency from very distant shores, the one thing that I thought his presidency had achieved was not only the exposure of the complete corruption of the media, and its willingness not only to lie, but to suppress the truth (the Hunter Biden lap-top was simply one egregious example of the media’s conspiracy of silence to get their man up), but to take the media head on. It may have not been as exceptional as we might wish to think, for media owners, and editors, prior to Obama taking office, to kill an investigation that might uncover a scandal that harmed their own political interests and investments. But when Obama became the commander-in-chief, as Jack Cashill has detailed in his Unmasking Obama, it became routine for what he (picking up on Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451) calls the “firemen” to protect the president from unwanted facts by “defaming opposition journalists, mocking their work, exposing their past sins, trivializing their information, and twisting their facts, among others.”

And while the media repeatedly said Obama’s presidency was scandal free, the fact was that just as he had firemen to burn the news, he was, as Cashill writes: “Like England’s Henry II, who reportedly said of Thomas Becket, “Will no one rid me of this turbulent priest,’ Obama seems to have led by way of suggestion. His henchmen and women did the dirty work. They sent Nakoula Basseley Nakoula to prison for making a video. They watched in silence as Lt. Col. Terry Lakin was dispatched in shackles to Leavenworth. They had James O’Keefe and David Daleiden arrested for undercover reporting. They cyber harassed reporter Sharyl Attkisson. They used search warrants on reporter James Rosen and several Associated Press reporters. They punished whistleblowers. They helped frame George Zimmerman and Officer Darren Wilson. They used the IRS to crush the Tea Party. They turned a blind eye to the New Black Panther goons. They conspired to clear Hillary Clinton of criminal charges. They discouraged all serious investigation into the death of Seth Rich. And even before the election, they breached Obama’s passport file and probably doctored it.” And they could do all this because the media was cravenly abetting in its silence and “fact-checking” to ensure the dreamer-in-chief was presented as the great unifier; and when Trump won the election, the same firemen and enablers had to breathlessly report on fires that more often than not were of their own manufacturing. And they thought that the public would not notice—and, to be fair, their public didn’t.

Some thirty years ago I realized that journalists were not that bright, tended to be ideological, and rather lazy – which is to say I saw them as much like the academics I knew (don’t get me wrong I am fairly lazy and pretty slow—I just hate ideology). But I had not equated the New York Times with Pravda. That was my mistake (being slow, I am also not that bright).

I only wish that as I was starting what would become my academic life, I had read and had had the wherewithal to really absorb an essay published in 1976 in the American Scholar, by a Polish émigré, Leopold Tyrmand, entitled, “The Media Shangri-La,” which exposes how corrupt and pernicious to US democracy the media was even in the mid-1970s. To my shame and regret, I had not even heard of Tyrmand till my friend, Zbigniew Janowski, who regularly shakes me out of my tendency to sloth, suggested I should read it and reflect upon.

Before discussing the essay in a little more detail, I should mention that two brilliant and important books by Tyrmand. One is as perceptive a book on life within communism as has ever been written—The Rosa Luxemburg Contraceptives Cooperative: A Primer on Communist Civilization. The other, Notebooks of a Dilettante, is a fascinating and brilliant series of observational vignettes on American life. One observation from Notebooks is particularly pertinent:

“Even among trained Kremlinologists in this country, there persists a common belief that the upper class in communist society is made up of party members, government officials, high-ranking military people, and industrial managers. Nothing could be further from the truth; these people are the rulers; those overburdened with work, gross, coarse, very limited, “half-or-quarter intelligent (as we call them), undemanding where a better life is concerned. They live modestly, work fourteen hours a day and are early victims of heart disease. The real upper class are those who serve them—the cynical intellectual, writers, artists, journalists who sell a preparedness for every lie in return for money and lack of responsibility… They get in exchange material prosperity, extensive travel to the West paid by the state, intensive sexual dolce vita, made possible by their exceptional social position.”

Communism and its mutation of progressivism was the invention of what Tyrmand calls the real “upper class”—those who live off the making and monitoring of narratives which the rest of us should live by. I don’t think the “rulers” in the West today have quite the grim life that Tyrmand ascribes here to the communist “rulers” he describes, but his depiction of the group he identifies as the “upper class” is very accurate—it is the class of people who talk, write, play, and want to be renumerated for telling others what and how to think and what and how to behave in the world.

- They are generally not interested in the hard sweat and compromise of policy and diplomacy;

- they are largely averse to risk;

- they do not wish to spend their time doing anything as boring as orchestrating and overseeing the productive deployment of material resources;

- they like reading, writing and gas-bagging, especially with people who think just like them;

- they are happy to morally condemn capitalism whilst designing (albeit without any detail) a new society in which capital would not exist; yet their interests align with those who do know how to attract massive amounts of capital and generate great wealth.

These are Nietzsche’s higher men and women, who (unlike Nietzsche) have discovered that if they purport to make the world equal, they will ever be served by clients who depend upon them—hence they are post-Marxists, and being post-Marxist means that they divide the world into oppressor and oppressed, and they receive the resources they need to live how they wish by instructing us all how not to oppress each other.

This conveniently fits the interests of that class of entrepreneurs and investors who want a compliant work force to produce what they think will be most profitable. This is the class of people who ensured that Trump and his goons did not destroy democracy. Of course, one only has to look at how the same people not only spoke about Ronald Regan, the Bushes, and a man who became a real sweetheart to them, John McCain, to realize how vicious they become if anyone stands in the way of their plans and interests.

Trump should have been the easiest of targets, and should have folded long before the 2016 election: he was a philanderer and cad; he was crude; he was vain; he was loose on detail; he was thin-skinned and petty, given to vengefulness over the most minor of slights, and seemingly incapable of circumspection. He constantly brought people into the administration who betrayed him and his program, and he frequently lost or turned against people who either loudly supported him, or were even brought onto the team with great fan-fare. This, though in large part, has to do with the class nature of the swamp problem that Trump had been elected to deal with.

Ann Coulter, who had supported him with such enthusiasm but was furious about his treatment of Jeff Sessions, called him out for being lazy, though—as someone who understands a thing or two about laziness—I doubt if sloth would really be brought up against Trump on Judgment Day. I think a more impartial observer might just note how many fronts Trump had to fight on because he could not find a supportive administration. In any case, for all Trump’s human flaws—he was no media pushover. At every opportunity, he called out journalists for being liars. And his supporters loved him for it. And as that happened the journalists and Democrats became ever more hysterical—they quite literally preferred to watch cities burn in “mostly peaceful protests” than have Donald Trump restore law and order.

The thing about any real democracy is that no one really gets what they want. When, though, people are unprepared to sacrifice what they want on behalf of a good that has been reached through contestation by accounting for differences in interests, then democracy itself is simply an impediment to an interest. Naturally, an elite of educated people think their interest is irreproachable. Hence, nothing is more evident to our elite than the “fact” that they are the incarnation of the good, the true, and the beautiful; and their mission in life is to guide the rest of us in ways in which we can all benefit from their goodness, truth and beauty.

Along with universities and schools, the media are our great saviours. And, as it so happens, they have managed to almost all line up as members, or outspoken supporters of a political party, which provides the program, policy platform, and plenty of jobs, and government funding for those who share its interests. Which is why Trump supporters have been saying for four years, the media is now simply the mouthpiece of the Democratic party—and, again, no wonder more than half the country does not trust the Media.

Workers in the Media claim to represent the public interest—when I first wrote this sentence, I had used the term the “national interest,” but it is incorrect to think that journalists care about the “national interest” when they are no longer in favour of national borders and hence of national sovereignty. The idea that there is a public interest which can be discovered and represented by anyone other than an elected representative, or, failing that, someone appointed by elected representatives, is very dubious indeed.

Though, one of the most dubious ideas that has, with the acceptance of the narratives and norms of identity politics, been presented as self-evident is that a person who shares a particular feature with others—gender or sexual identity, skin colour, etc.—is ipso facto a representative of others with that same characteristic. Thus, a presidential victory for a woman, say Hilary Clinton, would have been a victory for all women. Apart from this line of thinking being very self-serving—you should vote for me, Hilary, because I am a woman and am able to express policies that are beneficial to all women, etc.—it is obviously so silly that it was only believed by those women who shared the same values and wanted the same political things as Hilary Clinton did—as was obviously the case when Sarah Palin was mercilessly mocked by women and men who did not share her politics, and never hesitated to think for a moment that her gender made her a representative of women’s interests.

Conversely, we know that even the people who insist upon representation based upon identity are quick to jettison the primacy of identity when someone who is a black, woman, Muslim, gay—whatever—departs from the normative script about how a black, woman, etc. should behave. It is, then, understandable why a US citizen would say that the policies or pronouncements of the president do not represent what they think or feel, or their interest. But journalists are no more representative of the public interests, than butchers, bakers and candlestick-makers. Indeed, the one thing that is glaringly obvious is that their life-experiences have nothing in common with a large section of the public.

The larger media organizations also appoint the people with the best educational pedigree, which is to say, and to repeat my earlier point, that they appoint people who think like the people who trained them in how and what to think about social and political issues. And although academics generally claim they encourage independence of thought—they rarely do. From the perspective of an academic, whose bread-and-butter commitment and economic renumeration are built around identity, someone who argues against the idea that women or blacks or LGBT or Muslims or whoever, experience the world as an oppressed group is simply not thinking.

Given that much more than half the population do not think like “identitarian” academics, bureaucrats, or activists indicates that at least half the population are not thinking—which is why, amongst other things, incorporating critical race theory into the training programs within public institutions and private corporations, having policies on pronouns, ensuring that hetero-sexuality and cis-gender-ism are de-legitimized within the school system are so important for making the rest of society get with the program. Thus, too, any journalists who do not go along with the various ethical proscriptions against values, which are now “obviously” conservative, white-supremacist, sexist, etc. must not be employed, and if presently employed, they have to be fired. Journalists, though, are only part of the “cabal”—to use Molly Ball’s phrase again—students, and indeed anyone with a moral conscience, is required to report on anyone who might say or think such things.

But the progressive sense of morality is as haphazard as it is bizarre as it is self-serving. Our journalists feel it their duty to scout out and destroy any non-black (they do not like—double standards are rife, of course) who somewhere, sometime used a word, irrespective of context, which is endlessly spouted in rap or street talk, while having no interest in the role that our Hollywood moguls, the super-rich, celebrities, rock stars, and well-heeled urban professionals play in supporting an illegal product, the production of which is predicated not only upon the murder of tens of thousands of people, including women and children, but the corrosion and corruption of states.

The journalists, who joined the celebrities who made such a moral to-do about open borders, rarely (if ever) connected the refugee problem with the recreational drug issue and the class of people who it involves—to be sure, not only, but primarily, its audience. The moral line, though, whilst haphazard in terms of content, is consistently self-serving—the greatest moral enemies, who must be hunted down and destroyed, are those who speak out against the progressive spin and program.

This too is why Big Tech had to get in line with universities and other corporations, who have an ethical brand/image to protect and ensure that none say things that are hurtful and harmful, whether it be racist, sexist, Islamophobic, etc. Journalists play their role by identifying anyone who is caught saying or doing something racist, sexist, homophobic, etc. Thus, the never-ending daily stories outing “Karens,” racists, homophobes, etc. It does not matter whether the culprit is famous or not—they will soon be infamous, and have their life pulled through the media, so that they will in all likelihood lose their job.

Though, given that celebrities and sports stars belong to the good, true, and the beautiful, the program benefits drastically by discovering that sometime, somewhere, some high-profile figure did something, or said something contrary to the speech required of the program. Of course, people being what they are, some get more chances than others. Biden and Bill Clinton were held to very different standards on the matter of sexual harassment than various other characters who lost their reputation and livelihoods for deeds far less nefarious than these two presidents were accused of doing.

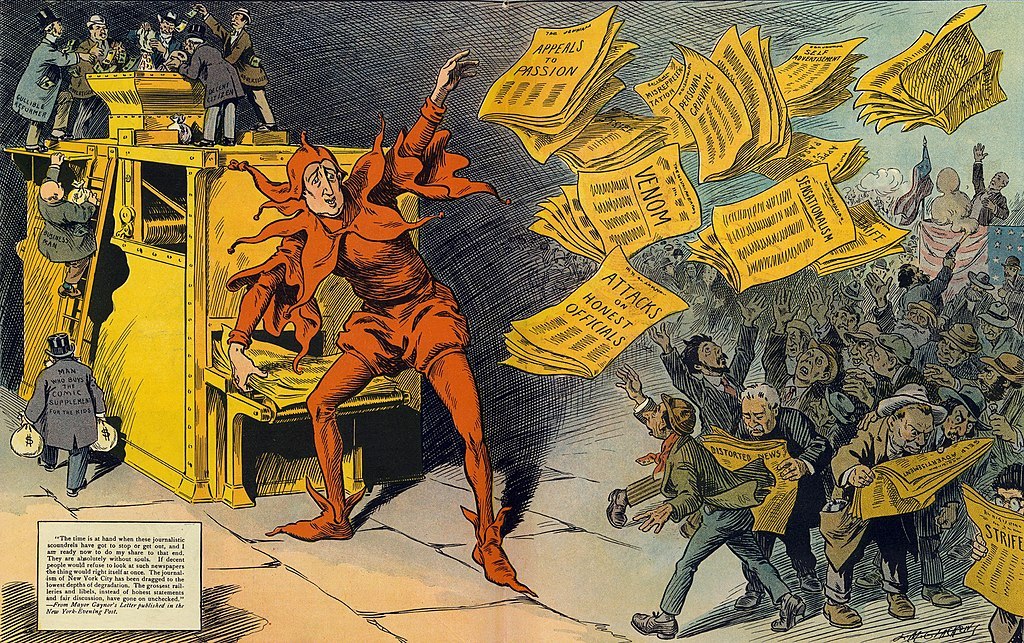

In a previous age, accusations alone were not generally seen by journalists as adequate for destroying someone’s reputation and livelihood (though the press has always been willing to use this in exceptional circumstances, now it is commonplace).

So while the media has always had its nefarious tendencies, those tendencies were more easily mitigated by its more limited reach. That reach and media scale, though, have expanded over the decades to fill in the gaps left by a world where in the larger cities people’s daily lives are increasingly confined to smaller areas of “thick” social connections. Thus, the disparate levels of trust in the media are connected to the kinds of daily social interactions people have in larger urban centres in comparison with those of people in regional and rural areas. The urban centres are full of people who think they are very intelligent because of what they read, watch, and repeat to others who share the same sources of information and make the same associations—”How could you distrust The New York Times?” they think, shaking their heads in disbelief, when they watch some redneck say things they have long since branded as racist, dumb, or part of a conspiracy theory?

But those who don’t spend their free time watching movies, tv, or reading the newspapers because they think they are garbage, having little to do with reality draw upon a very different set of life experiences. Their experiences make them think: “How can those people push their heads so far up their own behinds they do not see the obvious craziness of what they are saying?” And, as much as it is a surprise to the city slickers, they don’t much care for people who don’t know them, calling them racists and rednecks and imbeciles.

They also don’t roll over and lie down and grovel when a wealthy group of people who have gone to the best schools, earn very good money, and are mostly white, berate them for being white privileged, even though most of them are struggling to meet their mortgage, car payments, kids’ school tuition, etc. They could not choose their colour and most of them have done their best with the far more limited choices at their disposal than the smarties who have gone to Yale or Stanford and speak of them as human trash. They put in to their communities, they are generally good mannered and friendly to strangers, and do not bear people ill-will without cause.

Of course, they know they have their share of bad eggs; but they generally know right from wrong, and don’t dream up smart phrases so that they can no longer tell one from the other. Calling killing a baby “planning one’s parenthood” takes real sophistication and does far more danger to one’s sense of reality than merely taking the sting out of one’s conscience—as is evident when the serious moral dilemma of sacrificing a child to save a mother’s life is put on the same moral plane as the argument that a growing creature in the womb is nothing more than a finger nail. But that is where our “learning” has taken us.

The deplorables might not have gone to these palaces of learning, but they know a con when they see it—they know the people who mock and belittle them can no more have gone to the best schools and been oppressed than 2 plus 2 can make 0. So they also are perfectly able to recognise that when someone says that any member of an oppressed group should be believed, he doesn’t really mean it. They know that the people who say this are habitual liars, who have so lost their moral compass that they do not know they are habitual liars. Hence they do not even notice how haphazard they are in applying their moral standards—if you have the right politics and if you have the right friends your past manslaughter (for the young Ted Kennedy), past black-face (Trudeau) won’t count any more than your sexual harassment.

As night follows day, moral violations become increasingly stupid—cultural appropriation, micro-aggressions join the kind of offences that Lenin, Stalin and their henchmen had to dream up to clear away the old elite to make way for the new. To know what is expected, thus, becomes impossible to consistently maintain. Likewise, the equivalent to the once good old Bolshevik has been discovered to be an enemy of human kind—they may think biology matters, they may have thought it was funny to display their lack of rhythm or inability to do black street talk, they may have dropped a wrong word in a joke. They will all be denounced—or if too important, the media will ensure that their past crime will disappear—all who are found out will publicly repent, hoping they can maintain their career and fame and/or status—and if they do get a second chance they will be at the front of the queue at the next public denunciation. Some will be cast into oblivion and their past deeds will go the way of Eric Coomer’s anti-Trump Facebook posts.

Again we can all see this; but one group has enabled this and thinks it is the way to making a better world; while those who have not lost their minds wonder what planet someone is living on who thinks that good grammar or wearing a sombrero to a fancy dress party is racist. And again, the fact that journalists as well as the rest of the cabal cheer along with this, only shows people who have real connections, relationships, commitments and concerns that they are completely devoid of any understanding of real suffering and real humanity. The old adage “sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me” might have simplified the matter; but when kids were taught it and chanted it in schoolyards around the country they were reminding themselves and each other that they were resilient and need not wilt when someone said something mean about them.

There is, though, no wisdom in believing that people are so fragile that they will be shaken to their very core and might never recover from a mean or stupid slur. Contrary to what the average journalist and college teacher now seems to believe, people do not need an endless set of protocols, laws, and punishments to stop everyone saying mean or stupid things. People are generally very capable of telling people who are rude to shut up. But an elite who live off instructing people in how to behave need to amplify the pain and sorrow along with the scale of meanness so that it includes entire groups. They target groups by promising to deliver them from the pain of humiliation, and they offer careers to a small number who they can get into the club; but most of what they deliver are words, dependency, family break-down, and impoverishment at an economic and spiritual level.

What I have just described is familiar to everyone—the program is articulated and pushed by all manner of people in all manner of professions and though it is paid for, and backed up by punishment, its success come from the fact that the class which aims for total control of information, normative narratives and associations is every bit as socially powerful as the clergy were within Christendom (the blogger Curtis Yarvin, aka Mencius Moldbug, speaks of its core ideational commitment being akin to the Cathedral). Just as the Church was both the expression of the faith of its members, and a vast employment agency, the political success of the new clerics of the new faith has been in not only creating ever more employment opportunities within the public and private sector to expand their faith, but increasingly ensuring that people who do not embrace the faith become unemployable, and denounced (indeed it is telling just how often the word “denounced” is used today).

There is no real division over the facts about some people losing their careers for saying or doing certain things. But people are deeply divided over whether this control and suppression of speech is a good or just thing. Likewise, people are deeply divided over the key tenets of social justice, including the idea that a specific aspect or personal feature constitutes an identity. That idea, in turn, has becomes central to the demand about how to think about people who share the same features. But if one thinks this is a really bad idea, then none of the attempts to distribute opportunities and resources, based upon that essential feature (that essence), amount to anything other than bad outcomes.

Likewise, no matter how much one bullies or denounces them, many people simply cannot accept that the way to solve certain social problems has been best laid out by critical race theorists, queer theorists, post-colonialists, et al. Likewise, many people simply do not accept, in spite of being told repeatedly that they are stupid or evil if they don’t see all women, or blacks, or LGBT, etc. as more or less all the same because they are women, etc. One does not have to be a poor white to think Oprah is full of it when she identifies herself with the most oppressed people in America because of her race. One does not have to be white to think that not all whites are racists. One does not have to be a man to think not all men are rapists.

Likewise, one does not have to be gay to think gay people should not be persecuted. And people may disagree with the rights of a gay couple to be parents without wanting to harm gay people—whether rightly or wrongly they can provide reasons for why any child might be better prepared for life by having a mother and a father. On this, and everything else besides, people see things in very different ways; and lots of people do not like being told how and what to think. But for those who not only like being told what and how to think, but who like telling other people how and what to think, these people are the problem. And they should go and get a good education, and if they cannot get into a college, they should watch the tv shows and movies which tell them how to behave, and watch, listen to or read the right (I mean left) media.

All of this which is clear now to anyone who does not like the program, nor much care for screaming youth burning down buildings in the name of racial justice, nor journalists telling them that the looting and arson they have been watching is mainly peaceful, or telling them that Antifa members smashing windows in the Capitol as they marched with MAGA supporters were not Antifa people, was obvious to Tyrmand back in 1976. He wrote then that the media in the USA had not only “appropriated, and mastered all the potentialities and subtleties of contradiction,” but had “monopolized” them so that “nobody will be able to effectively contradict the media.”

By the 1960s, he observed, the media, had already “transcended the traditional areas of influence—politics, for one. Larger targets were sought, perhaps the American soul or the totality of American life, so that either of these could be encompassed and shaped according to commandments that were never made clear, but no doubt existed.” To this the only qualification I would add, is that politics had been redefined in the 1960s to coincide with the personal.

The divide taking place in the United States was between those who were controlling narratives, and the ordinary people who smelled something very fishy going on in the stories they were reading and hearing. Given that there may be readers who cannot access this essay, I quote at some length:

“In the democratic ethos, we try not to hate but rather to despise, scoff, disbelieve; bigots hate, but normal people are disgusted by something or can’t stand it. In totalitarian countries, normal people hate in ways that denizens in democracies are unable to comprehend. It is a dark hatred rooted in the necessity to live at the unmerciful mercy of those who hold an unassailable monopoly on governing, informing, and, speaking out. Sometime during the sixties, a similar revulsion sneaked into the feelings of many Americans. The suspicion that “that you can’t beat them whatever you do,” which seemed to have been forgotten since the pre-labour union subjugation to the company store, made its reappearance as the people took a stand against the gemmating power of the media. Vietnam, student unrest, the Black Panthers. Permissive mores, and Watergate—coupled with the absence of any serious and sustained expression of opposing views—triggered in many people something stronger than disgust. The official beatitudes of the freedom of the press were trumpeted as articles of faith and key to Americanism. And the more these were preached as our common good, the more obvious it became that not everyone can bask in them; that among all of us who are free to express ourselves, some are freer than others, and to such a degree their freedom becomes out enslavement. Against this accusation, the editor barons would understandably reply that nay limitation they imposed must be looked upon as. a technicality, such as not enough space to present contrasting views, whereas any demand for checks and balances from them would signify an eventual collapse of liberty. It became clear that if truth is the victim of censorship in the totalitarian state, in America it falls prey to the manipulations that breed bitterness, a sense of bondage, and finally, hatred. Of course, the hatred can’t be ascribed to too many—only those who care about accuracy and equity and are tormented by it.”

I think it fair to say that since Tyrmand wrote this essay, the hatred expanded along with the sense of self-righteousness of journalists, which had, in turn, grown along with the self-righteousness and certitudes about the obstacles to emancipation and justice within the universities. Then came the Internet and cable TV. Millions turned away from the traditional media to find a platform. Trump was not only far savvier than any other politician about how to use social media, but he also gauged who was using it and why.

Trump-haters and Democrats seem to have never understood the extent to which people turned to Trump simply so that they could think independently, simply because they were sick of friends, family and everyone else in their circle telling them X, when they themselves were curious enough to get onto the Internet and discover if what was being said about X was truth or lie. People discovered there were lots of lies—lots of fake news. Or as Tyrmand said back in 1976: “All in all, the idea of information has been reduced to the attitudes of modern liberalism.”

Thus, when the gay New Yorker and former liberal Democrat, Brandon Straka, put up his story on Youtube about how he was ostracized and bullied by his liberal friends when he could no longer reconcile what he saw and heard with his own eyes and ears with some of the claims being made about Donald Trump, his video went viral. Hundreds of people quickly followed and made similar videos telling their stories—some were gay, some were trans, some (quite a lot in fact) had voted for Obama or been strong supporters of Bernie Sanders in 2016 (some had even worked on his campaign). To be more precise, they all told the same story: as soon as they reported back to their friends and family that they had discovered on the Internet something which indicated that what they were all accepting as a fact was not a fact, they were bullied and ostracized, attacked on Facebook, or Twitter. They just needed a platform to connect with people who had been ostracized and bullied in the same way; they wanted to be reassured that they were not mad.

BuzzFeed quickly informed its readers, in all seriousness, that the videos of the Walkaway movement, as it became known as, were created by Russian bots. And as much as BuzzFeed, CNN et al. wished to brand as fake-news, the narratives, information and even experience which they wished to discredit, it was the extent of their own collusion in the Russia election interference narrative and such eagerness to find Russian bots as BuzzFeed had found that was pivotal in people refusing to read or watch fake-news, and dive deeper (the term “deep dive” became commonplace, along with such terms as, “go down the rabbit-hole,” “red -pilled”) into the seemingly endless investigations people were conducting from basements where they would interview people and find audiences from all over the globe.

What was becoming apparent, is that the Media had followed the universities in losing any authority with well over half the country. And again, anyone whose livelihood and prestige were based upon the status of where they had received their education or where they were working was directly affected by this rebuke. Naturally they would get angry and bite back. They were losing clients.

The theme of client loss was astutely and repeatedly and very vocally picked up by black youtubers like Candace Owens, Kevin from Kevin’s Corner, Karen Kennedy, Jericho Green, Anthony Logan, Diamond and Silk, the Conservative Twins and many more—their common message is that the Democrats are the plantation party, that they make permanent clients of blacks, and that the way to a better life for black Americans is not to be found by black men not taking responsibility for their families, turning to crime, becoming a crack addict or selling drugs in the neighborhood. Nor is it to be found in welfare money or other freebies and white leg-ups, like easier entrance conditions for college, which all cement one into a clientelist position. They know that the reason why anyone—except the lucky few, whose inherited fortune may cost them their soul—gets ahead is by behaving well, putting in an effort, going to school and working.

Generally, they don’t like white college kids urging on rioters to loot stores owned by blacks as well as whites. They don’t like poor blacks being the means by which some white or even black college kid gets credit in their social justice class. They don’t like seeing black neighborhoods destroyed, and creating the conditions of gentrification for people from elsewhere to later capitalize on by swooping up cheap property. And they also do not like what they see as the genocidal culling of the black population by abortion becoming a key plank in the Democrats’ social policy.

Thus, their refrain is: white liberals deploy the narrative of systemic racism and white privilege to beef up their own privilege, and they are prepared to sacrifice everything about America that has made it a wealthy and relatively free nation to achieve their ends. They do not think that the expanse of blacks into the middle class is insignificant or bad—what astonishes them is how ignorant so many white ostensibly educated people are who have no idea of the demographics of the blacks in the middle class or even below the poverty line.

In sum—they smell a rat—they call it (as anyone knows who listen to these pods) the “DemocRat.” No wonder they are called Uncle Toms—if too many blacks thought like this, the game would be up. In fact, the game would be up if too many people of any color, ethnicity, shape, or sexual proclivity just happened to think more along the common sense lines of Mum or Pop who work in a café, or a gas station, or run the corner store, than along the zig-zags and spaghetti-rationales coming out of the educated places which cost you a hundred grand or so to learn what to think.

Again back in 1976, Tyrmand asked the simple question: “Why should a tidy old lady who does not believe in welfare, and feels that democracy ought to defend itself against dictatorship, be called ‘pig’ by a mob of untidy wild-eyed detractors with hackles up?” The same mob, though now far more poorly dressed, were out in full force over last summer burning stores and looting in the name of George Floyd.

One image around that time, I found particularly arresting: it was of a young, white woman, possibly late teens or early twenties, yelling at MAGA supporters who were trying to protect their neighborhood from being burned to the ground, screaming, “I hope they rape your children and kill you.” It was the kind of derangement that the most of the media did not bother reporting, because there was nothing strange or wrong about it: she was fighting for the same things as “the cabal”, unlike that schoolboy with the MAGA hat who was hateful to a native American (the ethnic identity was very important) dancing around playing a loud drum and staring him down: the hateful act consisted of—looking back at him!

BLM’s call for defunding the police and opening up the prisons as the race riots (mainly led by white college kids, or the feral off-the grid dropouts who think the way to freedom is to burn the lot down, while waiting for blacks from the underclass to up the ante and be the visible face of the looting) was but a repeat of the refrain from the 1960s and 1970s. Their social vision was the legacy of 1960s and 1970s anti-establishment radicals who are now establishment educators, such as Angela Davies; she supplied the weapons that killed three people in the attempt to free her lover George Jackson from prison, and she is now a Professor at the University of California; Weatherman founder Bill Ayres—he was a partner with Obama in the 1990s in the education foundation he had initiated, the Chicago Anneberg Challenge, and it was from Ayres’ house that Obama launched his first senatorial run; and, one last example, Eric Mann, also a Weatherman leader, who had been imprisoned for conspiring to commit murder, and is now a full time activist and speaker whose star “pupils” include Obama’s green energy “czar,” Van Jones and BLM founders Patrisse Cullors and Alicia Garza. The list goes on and on.

Again Tyrmand’s observation about how the journalists of the 1960s had sided with the criminal class, and prison rioters, by blaming social conditions for their existence is perfectly apt for today’s journalists: “They would never mention that the prison rebellion by now an American folklore staple, is an offshoot of latitude and permissiveness…Over the last quarter-century, the liberals and their press have had their way with crime in America, but neither expanded welfare nor the most lenient judicial and penitentiary procedure have brought anything but the wildest proliferation of violence.”

The following passage by Tyrmand encapsulates what he calls “the deviousness of the factoid” of the contemporary journalist when it comes to the matter of race in a story:

“Time once reported how a black man in Detroit, in a fit of rage, killed his factory foreman and two other men. The story was peculiar in tone: the magazine did not condone the killing, but its social conscience extended to a comprehensive discussion of why this would occur in a racist sweatshop. Shortly thereafter I met on Broadway a Time editor I knew. When I conveyed my doubts to him, he replied: ‘The most amusing thing is that one of the victims was black too.'”

In sum, Tyrmand realized that the liberal position in the 1960s was already being shaped by radical journalists, writers and hip philanderers who lionized terrorists, prisoners, and murders, including those of your more garden variety thug, such as, Jack Abbott, as well as ones with a more far reaching-social program, like Huey Newton. Since then, though, that view of the world has now become the norm among the elite. Thus it was that Trump voters were only showing their ignorance when they took Antifa’s existence and destructiveness seriously. Antifa, as Joe Biden astutely noted, was not an organisation but an idea—which is, by the way, straight from Antifa’s own program.

Though the powers that be at CNN, NBC and Australia’s ABC unwittingly confirmed, when they paid for camera footage from an Antifa activist’s “live shooting” of “the insurrection” of January 6, that Antifa has human members and not just ideational ones. Indeed, had they been interested in finding out how Antifa is paid, or who is in it, and which journalists go along with it, they might have bothered to interview conservative youtuber and business man, Joe Oltmann who had done the kind of thing one used to associate with journalists: he went undercover to get a story about which journalists had connections with Antifa.

In that meeting he stumbled onto an even bigger story that the media would only ever refer to as a conspiracy story, if ever it was even mentioned: the director of product strategy and security of Dominion voting system—yes, the system used in over twenty-four states in the 2020 election—had been merrily posting on Facebook Antifa’s program, along with his vitriolic hate toward Trump and his supporters. They have since been disappeared. Oltmann says that he heard that director—Eric Coomer—say at that meeting there was no way Trump could win—he had, reported Oltmann, made “effing sure of that.”

It is possible that Oltmann may not be telling the truth, though having watched hours and hours of him on Youtube, he strikes me as far more believable than most journalists and politicians, who want to tell us what we must think not only about the election of 2020, but pretty well everything from the weather to geopolitics, and how to solve problems of race and poverty (which amounts to, believe what we say and vote Democrat).

But of all his many masterful insights, the one point that Tyrmand makes which speaks so much to our time is the way in which Media has set itself up as the Ministry of Truth. I could not agree more with Tyrmand’s observation that governments “in democracies are disposable.” This indeed is the very reason why democracies as such are more important than the government within them. Policies can be right or wrong, they can serve this or that interest, and they can be changed—which is not to say that changing them will always be easy.

But when the press supports a government or some set of policies which are no longer beholden to democratic processes, then this an altogether bigger problem.

There are many policies which have long since become unhinged from any democratic input, but the one that had most impact in so far as it led to Trump’s election and the compete upheaval within the Republican Party was, of course, immigration. (There have, though, been plenty of Republicans who have no idea of what has occurred and think they can continue to remain in power by being the diet version of the Democrats).

The battle over illegal immigration is really a battle over the power of demographics. Just as it is commonplace for states to engage in ethnic or religious population shifts, to dilute the political power that flows from a particular group’s demographics; an elite that has lost its base must dilute the power of the old one by recruiting a new base. This is as much an occurrence in Western Europe as in the USA. And just as multiculturalism was an elite consensus policy rather than a party plank in an election platform, the widespread tacit acceptance of illegal aliens within the country and the workforce was never subjected to electoral decision—and this was as true for the Republicans as for the Democrats.

After Trump’s election, though, the tactic was vehemently defended by the elite and the media by calling those who wanted national sovereignty, racists. Thus, too, the substitution of the word “migrant,” a word whose meaning contains the tacit ring of legality, for what had long been the descriptive term for people who refused to comply with legal entry requirements to the country—”illegal alien”—was orchestrated by the media and Democratic Party. It was a typical elite tactic—and it is seen as such by the base, who are not so stupid that they cannot see that their displacement is a major piece in the elite’s program. This is also why it was the most important reason for people who wanted to retain what little socio-economic power they still have and who have suffered from the destruction of their communities, the rising crime caused by a great influx of people with nothing to lose or little to fear from the police and legal system (which tacitly and often overtly condones their presence) to ditch the old Republican-style elite politics for Trump.

The media has always been mendacious and duplicitous and journalists lazy, and pretty sure that they know best—but the monumental lies the media has engaged in the past four years were simply more rabid because Trump’s base was fighting back. But as Tyrmand observes, the monumental lie was part of the media’s arsenal fifty years ago:

“As of now simplisms are secondary; monumental fallacies get erected; The managing editor of Time says coquettishly in an interview: ‘We could never quite figure out whether we were part of the Establishment, and if so, how to deal with ourselves.’ An absolutism firmly in the saddle begins to mince and simper, The Democratic Big Brother longs for love and camaraderie.”

I would just add that none any more is in doubt whether the media represent the Establishment. And as the Establishment, it knows that its job must be to ensure that certain truths never see the light of day. Yet fortunately for those who think that being brain-washed is having a moral conscience, is it a lie if the person ensuring that a truth does not see the light of day simply makes sure that no one actually investigates it because it is beneath them? (The sneer, the snoot, the guffaw and the eyeroll are the ever-ready-to-hand responses to anyone who thinks that they can quote any old conspiracy theory that has not been sanctioned as newsworthy by real journalists). Such was the key response of the media to the Biden family’s interests in Ukraine and China.

There was no shortage of evidence about Burisma, or Hunter Biden’s qualifications, or the family connections with China, or Joe Biden’s role in the show. It just wasn’t to be found in CNN, MSNBC, the New York Times, Washington Post, etc. and none of the journalists who worked in such places were interested in following up on the kind of information that Peter Schweizer or the Duran were regularly digging up—it was far more important to find out if someone else might have used the “n” word somewhere sometime.

Reading Tyrmand, whilst watching the moral and intellectual collapse of Western institutions, is a bracing affair. It reminds one how long the collapse has been going on. I very much doubt that even five or six years ago almost half the country would have thought that a coup could have taken place via election fraud. In spite of the media and Big Tech and academicians insisting that this is crazy talk, half the population believes it, and the question of which “evidence” is to be believed has been shut down, along with the de-platforming of ever more people from social media companies. The fact that the New York Times could publish an op-ed piece calling for the government to appoint a Reality Czar to eliminate “disinformation,” or that journalists say without blushing for shame at their own stupidity that millions of people need to be “deprogrammed” illustrates why the moral and intellectual collapse in the US is from the head down.

The biggest problem of all, though, is not solved by knowing how dumb and dangerous the ideas that are now the bread-and-butter beliefs of the elite in Western democracies generally and not just the US. The biggest problem is that all elites are bred over generations, and that the bad ideas that have been accumulating for more than two generations are now so instantiated in the universities, media, the schools, business, in legislation and political parties, and have become central to the way so many people speak and think, it is hard to envisage how they can be undone without it playing out to the bitter end.

Unfortunately, the bitter end also involves the geopolitical advantage that is created for enemies of the Western world who are the real beneficiaries of Western liberal democracies tearing themselves apart. Our species pays heavily for its sins—we think we are building a tower to heaven, but we fail to see all the pieces of what we are making, and by the time people can all see that what we have been making and are now using is a giant scaffold, it is too late: the propaganda merchants, the informants, judges, prison guards, executioners, et al. are already stakeholders in a system that they service and which pays their wages.

It is a great tragedy that our university teachers and journalists, and the elite, as such, think that their simplistic principles and programmatic solutions will solve the “problem” of oppression and thereby fortify the bonds of communal solidarity—and they really think they can achieve this globally. They are so arrogant and ignorant, they seriously think that Africans, Indians, Chinese, Central Asians, and Muslims—almost everyone outside the USA except Western Europeans, and other “satellite allies” such as Australia—love them and what they are doing. Communal bonds, though, are not the expression of abstract systems of ideas, but ultimately of human hearts; and human hearts, being susceptible to pride, sloth and the other deadly sins, are far easier to corrupt than to nurture and nourish through love, charity and forgiveness.

Were our ideas-brokers more attuned to the fragility, endless mutations, tragic colliding contingencies, and shreds and shards of decency and conviviality, and were they less sure of their own intelligence, far more skeptical of their ability, and more willing to reign in their ambition, they might just be a little better in understanding how vastly complex the forces of evil are, and how little any of us know, and how rarely our plans turn out the way we think they will.

Gaetano Mosca’s magnificent book Ruling Class makes the compelling case that all societies have a ruling class. The problem with our ruling class is that while they relentlessly screamed and shouted that a real estate mogul and reality TV star, who at least knew what half the country was thinking, was unfit to rule, the last four years have proven that they are the ones who have shown to that same half of the country at least how unfit they are to rule.

Their unfitness is all too evident in that the best candidate of their preferred party was someone:

- who had pulled out of an earlier run because of plagiarism;

- someone who had sung the praises of Democratic senator and one time KKK member Robert E. Bird (if the Democrats were consistent in accepting that we all make mistakes, this might not be seen as so egregious);

- whose own Vice-President pick had implied was a racist during the Democratic run-offs – actually Fact Checkers provided the appropriate nuance for all the idiots who could not gather the sophistication of her criticism, which did not actually amount to racism: “Contrary to claims in viral internet posts, Sen. Kamala Harris did not call former Vice President Joe Biden a ‘racist’ or a ‘rapist.’ Rather, she has been critical of Biden’s position on busing to integrate schools and comments he made about segregationist senators, and she has said that she believed women who accused Biden of making them feel uncomfortable.” She did not call him out, though, for the sheer stupidity of statements about racial groups he seemed to endlessly conjure up to no specific end;

- whose creepy hair sniffing and age inappropriate wink-wink banter with children could easily have made him tabloid mince meat;

- whose claim to believe all women did not amount to a woman who accused him of sexual assault.

And that is before one even starts on the family corruption. The media have tried their best to cover up the China, and Ukraine money trails – but for anyone interested they might also want to look into “S.Res.322—A resolution expressing the sense of the Senate on the trial, sentencing and imprisonment of Mikhail Khodorkovsky and Platon Lebedev” and wonder why he was doing the biding of Russian oligarchs charged with tax avoidance. Normally one would not need to point out that Putin being an autocrat does not make these two plutocrats “good guys,” but with the successful rebooting of the Cold War it would seem that any opponent of Putin is on the side of the angels, irrespective of how much blood money is on their hands.

And, finally, there is the whole question of his mental state. Although the media made much of the question of Trump’s mental health, some half of the country could see that one guy could speak seemingly endlessly off the cuff to large crowds which had a party atmosphere, whereas the other conducted a campaign from the basement, and when he did go somewhere, one wondered where was everyone. And when he did something, the problem for his minders was not so much that he might babble something not coherent enough to do the grammatical damage that a sentence of Trump’s might do, but that he just might end up saying something grammatically correct, such as: “We have put together, I think, the most extensive and inclusive voter fraud organization in the history of American politics.” I am sure that many people did not know which was more hilarious—him saying that or that Fact Checkers had to say that, yes, he did say that, but the context indicated that that was not his intention and that he had misspoken.

All of this amounts to the fact that if the election were merely fortified and if Joe Biden was seen as the savior not only of the nation but the global order, then the USA and the world were in deeper trouble than anyone had heretofore imagined. Nevertheless, the media band played on and saw to it that we could all get behind “our Joe,” as if he knew exactly what he was doing – surely, the media line went, he had proved himself by his more than fifty years of public service by doing… apart from making himself rich, and bragging about his biff ability, none of them—or the rest of us—seemed to really know. The way the media spun it and even people way down here in Australia bought it, it was a choice between Trump and preserving everything good about everybody’s way of life on the planet: back to Paris, closing down coal mines, stopping fracking, boys being girls competing in school sports with girls and using their bathrooms, critical race theory shoveled down the throats of public servants, China back in the saddle as the chief beneficiary of US trade mishaps and geopolitical stuff-ups, getting those employed minorities back into their client position and the whole caboodle of what had been all going so swell until that Hitlerite orange turd stuffed it all up by wanting to get all Americans to work, get a better trade deal with China, apply the kind of immigration policies that are pretty well standard in every Western country, provide cheaper pharmaceuticals, avoid foreign military interventions, provide better support for the widows of veterans, and generally better pay for the armed forces, and greater support for the police, and defend traditions, such as, standing for the national anthem, and having the temerity to want to protect statues and the names of military bases of people who fought on the side of the confederacy.

And finally when “our Joe” won there was only one more hurdle: inauguration day. I heard a podcast from the American Mind where the discussants were saying how the spookiness of the image would be long remembered. Certainly the inauguration was unforgettable – an almost deserted Capitol, fenced in by razor wire and guarded by over twenty thousand (vetted) national guards protecting a masked inauguration from the great fear of another insurrection of those deranged Trump supporters, who all called for law and order, when the Democrats carefully explained why it was just and righteous that people express their rage against racism, why it was constitutionally wrong to use the national guard to stop looting and burning, why the party should defund the police, and provide more community education left-wing blah blah blah. And yet again at least half the country simply could not believe this was America; those who wanted this outcome saw only good things. Fox journalist Chris Wallace gushed it was “the best inaugural address I ever heard” – it was “part sermon, part prep talk.” The religious character of the whole show was a pretty common theme among the journalists—who gave the impression that they were as knowledgeable about authentic religious experience as Joe Biden seems to be about his own Church’s take on abortion.

So, while almost all the journalists were deliriously celebrating their victory, and while victors were soaking up and sniffing up the spoils that lay before them through their fashionable masks, relieved that all could now proceed according to the right way history should go, with them doing the driving, millions of people who would never have made it through the razor wire and guardsman, not because they were itching for a violent insurrection, but because they belonged to the other side—the outside—saw a greedy, self-serving, deluded bunch of grifters, bag men/women and non-binaries, liars, sycophants, and know-alls, prepared to do and say any and everything to get their way.

More charitably, and in some ways more importantly, they saw an elite who had lost touch with their support base. In part that is something of a consequence of the kind of elite a modern democracy produces: it produces an elite whose members do not especially think of themselves as an elite – they can have enormous wealth and influence, can go to the best of colleges, and yet because of a specific feature they may have – it all comes back to the same basic list: who they like to have sex with, or their skin colour, or religious heritage, etc.—can represent themselves as victims of more powerful forces. Indeed, it is almost a prerequisite of being an acceptable member of the elite to have some feature of one’s self which is on the “disadvantaged” list.

Being blind to oneself is the first step on the road to a completely fantastical view of reality. And that is what separates the elite as much as anything from the support base whose life-world is built upon day-to-day practicalities like putting food on the table for one’s family. Of course, everyone has to have food, but the elites are elites largely by virtue of assuring that the food will be there for them first.

Just as societies all require elites (contrary to the nonsense that the elite itself endlessly writes about the “common,” the “democracy to come,” or, “fortifying democracy”), the issue is whether the elite actually provides a service to its base. When it doesn’t, it may hold onto power for a substantial period of time, but to do so requires permanently surrounding itself with the equivalent of razor wire and the national guard, and doubling down by persecuting those who see them for what they are. When though the opposition is at least half the country that is quite a difficult trick to pull off. Communist countries managed it for two or so generations.

What also makes it difficult are the surrounding geopolitical forces which gravitate to the weakened state like vultures to carrion. These invariably unsettle the best laid plans of a group determined to control its internal opposition so that it either has to make diabolical pacts with, and/or errors of judgments about, its enemies. In either case it seals its fate. The USA had been a masterful practitioner of taking advantage of its enemies’ internal turmoil; but now its elite have ensured the continuation of that turmoil. One only has to note how the Muslim Brotherhood, whose end-game is a universal caliphate, had been rebranded as “moderates” under Obama’s watch.

Generally the success of the present elite has gone hand-in-hand with a complete overhaul and politicization of the military, intelligence and local policing agencies. The brazenly partisan justification given by officials and former officials from the FBI and CIA for the surveillance of Trump and members of his team in the presidential run showed anyone who believed in the old USA that non-elected officials believed they were the true representatives of the will of the people; and as such the people should comply with their will. Meanwhile the media had done everything it could to support its “deep state,” regularly feting officials and getting them to write op ed pieces or give interviews justifying why they were the real protectors of democracy and hence were largely operating against the president’s interests and orders. As bad as the press were back in the 1960s, journalists could at least see that non-elected state officials should be beholden to the electors and constitution.

The account I have given of what the media have enabled is dire. But it would be remiss not to note that half the population or so recognize that this America and its elite are rapidly destroying the great achievements of old America—independent mindedness, initiative and inventiveness, and the formation of solidarity across racial (an achievement to be sure that required a civil war), class, and religious lines, an America, that is, where people from so many hells-on-earth would do anything to share its blessings and fruits. They do not, as the elite insist, wish to denigrate or humiliate or confine to servitude black or any other people, who live by the law and contribute their energy to making a nation which used to be the beacon on the hill.

The success of the elite in capturing all the major institutions of the nation is serious. Though, perhaps not hopeless. Institutions naturally deteriorate over time, and either they are rejuvenated or die. Within the media, when AM radio was all but dead, Rush Limbaugh discovered an opportunity, and created a power-house that gave voice to millions who thought they had none. Youtube has also provided all manner of opportunities that provided an alternative to the lazy hacks, liars, and “firemen.” Though its success has bred reaction, which in turn has opened up new platforms. There can be no doubt that monopoly interests will use the present state to shore up not only its own economic power, but its social and political power.