This biographical essay was published in 1917 (in the March issue of The North American Review). Although little know today, William de Morgan (1839-1917) was a well-known potter, tile-maker and then a widely read novelist, who was a friend of both William Morris and Charles Dickens.

The author of this essay, William Lyon Phelps (1865-1943), the American scholar, single-handedly promoted and popularized the novel in America, especially by way of his essays on various novelists, of which this is one.

It was in August, 1911, that I first saw William De Morgan. The meeting—ever memorable to me—took place at Church Street in Chelsea, in his own home, a building filled with specimens of his tiles and graced with his wife’s paintings. After some time, we adjourned to what the English call a garden and what is known in America as the back yard. He fetched the manuscript of a nearly-completed novel, A Likely Story, and read aloud many of the detailed chapter-headings, chuckling with delight (even as a diplomat) over the apparently candid profusion of language with the successful concealment of the writer’s intention. For example (A chuckle after each sentence):

How Fortune’s Toy and the Sport of Circumstances fell in love with one of his nurses. Prose composition. Lady Upwell’s majesty, and the Queen’s. No engagement. The African War and Justifiable Fratricide. Cain. Madeline’s big dog Caesar. Cats. Ormuzd and Ahriman. A handy little Veldt. Madeline’s Japanese kimono. A discussion of the nature of Dreams. Never mind Athenaeus. Look at the prophet Daniel. Sir Stopleigh’s great-aunt Dorothea’s twins. The Circulating Library and the potted shrimps. How Madeline read the manuscript in bed, and took care not to set fire to the curtains.

Mr. De Morgan was then seventy-one years old. He was tall and thin. The latter adjective comes near to expressing his entire physical presence in one word. Everything was thin. His body was thin, his beard was thin, his voice was thin. But his nature and his manner had all the heartiness and geniality we commonly associate with rotundity. He was in fact exactly the kind of man that the author of his novels ought to have been. What more can one say?

In the Spring of the following year, I saw Mr. and Mrs. De Morgan again, this time in their apartment on the Viale Milton in Florence. It was deep in the afternoon, and a pile of manuscript a foot high rested on the table, the ink on the summit not yet dry. “The American people do not like my last two books,” said he with a cheerful smile, “but perhaps they will like this one, for it is the most De Morgany novel I have yet written.” His hope and his statement were both justified, for the manuscript was the first part of When Ghost Meets Ghost. Unlike many writers, he found the morning hours unfavorable for original composition. ” I am an old man, and my vitality does not reach much strength until late in the day. I do my best writing between tea and dinner.”

We talked of the Titanic, and of the war that Italy had carried into Africa. At that time he and I, with all the difference between us that the possession of genius gave to him, had one thing in common: we were both pacifists. Knowing his passionate love of Italy, I feared that he would ap prove of the war, and glory in the certainty of Italy’s victory. I was happy to find that his love for the country and for the people did not blind him to the wickedness of that selfish and greedy war. … It is only fair to him to say that his pacifist principles failed to survive the early days of August, 1914. He was aggressively for England to his last breath, and his letters showed constant surprise at his own thirst for blood. Yet while rejoicing in English victories, he could not help deploring the loss of many brave enemies of his country. In October, 1914, he wrote to me:

I am sorry to say that I am barbarous by nature and catch myself gloating over slaughter—slaughter of Germans, of course!—half of them men I should have liked—a tenth of them men I should have loved. It is sickening—but…

Again, in December, 1915:

I put aside my long novel, because, with Kultur in full swing, I felt I should spoil it. I took up an old beginning—sketched in immediately after Joe Vance—and have got about half-way through, with great difficulty. The trail of the poison gas is over us all here, and I can only get poor comfort from thinking what a many submarines we have made permanently so. All the same, one of my favourite employments is thinking how to add to their number—a grisly committee—coffinsfull of men very like our own. For all seamen are noble, because they live face to face with Death.

In our London conversation he told me the now familiar details of his becoming an author. Never during his long life had he felt the least flicker of literary ambition. In his letters he was always insisting on the additional fact that he had never read anything: “I scarcely looked in a book, un less it was about pots and mechanism, for forty long years. There’s a confession!—a little exaggerated in form from chagrin at the truth of its spirit, but substantially true for all that.” As a matter of fact, he knew Dickens as few readers have ever known him, and he had many of the shorter poems of Browning by heart, though he never read The Ring and the Book.

If he had not taken a slight cold in the head when he was sixty-four he might never have written a novel. This cold developed into a severe attack of influenza, and as he lay in bed, he amused himself by writing the first two chapters of Joseph Vance. “If I had not had the ‘flu,’ I should not have thought of writing a book. I started Joseph Vance ‘just for a lark.’” He had in mind no scenario, no plot, no plan, no idea whatever of the course of the story, or of what would become of any one of the characters. He just began to write, and his writing ceased—forever, as he thought—with his recovery. The world owes his completion of the story to Mrs. De Morgan, who insisted on his continuing. Then he came near destroying the early chapters, for they seemed to him to be too much like Dickens. In 1905 he was half-way through Joseph Vance, and it was published in July, 1906, when he was sixty-six years old. Its rejection by a publisher, owing to the appalling size of the manuscript, its subsequent acceptance by Mr. Heinemann, who saw it only after it had been typewritten, and its instant success, are now matters of general knowledge.

In an article I sent him he was impressed by the “sudden” opening of a story by Pushkin, Tolstoi’s delighted comment upon it, the immediate challenge of a friend to imitate it, with the result—the first page of Anna Karenina. In 1910 he wrote to me:

I must give you a parallel case to yours. Somehow Good began thus: I had written a good deal of another story, and liked it. I read it to my wife, and she didn’t. She said, “Why can’t you write a story with an ordinary beginning?” I said, “What sort?” and she answered, “Well—for instance: ‘He took his fare in the two-penny tube. Said I, “An admirable beginning!” and put my story in hand away, and began writing forthwith what is now Chap. 2 of the book. Chap. 1 was written long after, to square it all up. But the incident was substantially the Tolstoi story again, and chimes with all your comment on it.

The above account of the origin of Somehow Good is the more interesting because, of all his novels, this has the most orderly and best-constructed plot, and, viewed merely as a story, is his masterpiece. Which does not mean that I would trade it for Joseph Vance. To my mind his finest novel is the first one, and his greatest character is old Christopher Vance. With all my heart I hope that the latest book he was working on was completed, for he wrote me that it was even more “demorganatic” than the demorgany Ghosts.

He was deeply interested when I told him that the John Hubbard Curtis prize at Yale University in 1909 was offered for the best composition on the three novels which he had published before that year. He asked if he might see the successful essay, which was written by Mr. Henry Dennis Hammond, an undergraduate from Tennessee, and published in the Yale Courant for June, 1909. Two copies were sent him; one he returned to the young author, with highly diverting (and important) manuscript marginal notes. These notes were accompanied by a cordial letter, from which I make the following extracts:

I have scarcely an exception to take. What I have is to he found among some jotted comments on the margins of the Courant that I return to you. I daresay you will see that your irreverence (shall I call it?) for Dickens has occasioned some implication of cavil from me.

But all you young men are tarred with the same feather nowadays. Your remark about the red cap in David Copperfield made me re-read the chapter. I am obliged to confess that the red cap is absurd—a mere stage expedient ! He would have seen the hair, like enough. But, oh dear! What a puny scribbler that re-reading made me feel!

Here follow some of the marginal annotations, which explain themselves:

I am a successful imposter about music—I know nothing of it—but am a very good listener… I must have omitted some distinguishing points in these folk, to leave the impression of similitude. You see, I know them intimately still, and can assure you that they are, as a matter of fact, quite different. Dear, good old Mrs. Heath was worth both the others twice over… Come, I say—isn’t it quiet, wise, and lovable to smoke cigarettes? Very!—I think: Still, it’s true poor Janey died before English girls took to ‘baccy… But then Dickens was my idol in childhood, boyhood, youthhood, manhood, and so on to a decade of senility—even until now… Concerning realism and idealism, I’m blessed if I know which is which!… the attempt is to found the ghosts only on authentic ghost stories with the same explanations, if any… The first meeting of David C [opperfield] and Dora covers any number of sins… Anyhow, folk read the stories, and there will be another Sept. 23.

Merely to call the roll of Mr. De Morgan’s works is impressive, when we remember their size, their excellence, and the short period of time in which all were written: In eight years this wonderful old man published over a million words, and left several hundred thousand in manuscript—every word written by hand. The mere mechanical labor of writing and proofreading on so gigantic a scale inspires respect. Joseph Vance appeared in 1906; Alice-for-Short in 1907; Somehow Good in 1908; It Never Can Happen Again in 1909; An Affair of Dishonour in 1910; A Likely Story in 1911, When Ghost Meets Ghost in 1914.

The romantic revival in modern English fiction, which negatively received its impelling force from the excesses of naturalism, and positively from the precepts and practice of Stevenson, flourished mightily during the decade from 1894 to 1904. Unfortunately no works of genius appeared, and it was largely a fire of straw. Then just at the time when three phenomena were apparently becoming obsolescent—pains taking realism, very lengthy novels, and the “mid-Victorian” manner—William De Morgan appeared on the scene with Joseph Vance, a mid-Victorian realistic story containing—after William Heinemann had exercised the shears—two hundred and eighty thousand words! Within a short space of time the book had just as many readers as it had words. This is what Carlyle would have called “a fact in natural history,” from which we are at liberty to draw conclusions. One conclusion is that William De Morgan has had more influence on the course of fiction in the twentieth century than any other writer in English. For he gave new vogue to what I call the “life” novel, which differs from the popular novels of the ‘eighties as Reality differs from Realism, and whose sincere aim is to see life steadily and see it whole. In England, Arnold Bennett published The Old Wives’ Tale in 1908; H. G. Wells published Tono-Bungay in 1909; and the same year marked the appearance in America of A Certain Rich Man, by William Allen White. These three books are excellent examples of the new fashion, or the old fashion revived, which ever you choose to call it.

Henry James has said somewhere that in the art of fiction and drama we experience two delights: the delight of surprise and the delight of recognition. Of these happy emotions, readers of Mr. De Morgan feel chiefly the latter kind; although Somehow Good contained plenty of surprises. Nearly every page of his longer books reminds us of our own observations or of our own hearts; and many pages drew from solitary readers a warmly joyous response. Even the most minute facts of life become so interesting when accurately painted or penned, that the artist’s victim actually receives a sensation of pleasure so sudden and so sharp that it resembles a shock. One cannot possibly read Joseph Vance or When Ghost Meets Ghost with an even mind.

It is true that William De Morgan wrote An Affair of Dishonour. But Dickens wrote A Tale of Two Cities; Thackeray wrote Esmond and The Virginians; George Eliot wrote Romola; and Charles Reade wrote The Cloister and the Hearth. Why should we have quarreled with him about that? Any realistic writer may surely take a holiday in the country of Romance, if he chooses to do so. Yet the American attitude toward this particular historical romance was positively hostile; so hostile, that not only did the An Affair of Dishonour fail from the publishers’ point of view, but the four novels that preceded it practically ceased to sell for a whole year; at least, so their author told me.

He took the rebuff good naturedly, and extracted humor from the fact, as the postscript to A Likely Story proves; but he could not understand why he should be “punished” for daring to write an unanticipated work. I tried to explain to him that the anger of the American public was in reality complimentary; that he had set so high a standard in his four novels that the expectation of a vast circle of men and women was enormously keen, and that from a man of genius we always expect a work of genius, which no man—except perhaps Milton—has been able invariably to supply. He was not comforted. Seven years have passed since the publication of An Affair of Dishonour; and it is certain that the book ranks higher in the estimation of intelligent readers than it did during the first months that followed its appearance. It is, in fact, a powerful story, told with great art; destined, I think, to have a permanent place in English fiction. It lacks the irresistible charm of the other books; but it is rich in vitality.

After reading the first four novels, I inquired of the author: “Why do you make elderly women so disgustingly unattractive? Does your sympathy with life desert you here?” And what an overwhelming reply I received in When Ghost Meets Ghost! Were there ever two such protagonists? Not elderly, but old—tremendously old, aged, venerable. And what floods of love and sympathy the novelist has poured out on these frail old waifs of time! How one feels, like a mighty stream running under and all through the course of this strange story, the indestructible power of the Ultimate Reality in the universe—Love, Love Divine.

This leads me to the final reflection that William De Morgan was not only an artist, and a novelist, and a humorist: he was also a philosopher. Each one of his stories has a special motif, a central driving idea. I mean that underneath all the kindly tolerance through which every great humorist regards the world, underneath all the gentle irony and the whimsicality, the ground of these books is profoundly spiritual.

William De Morgan, like his brilliant father, belonged to the believers, and not to the skeptics. He was of those who affirm, rather than of those who deny. He was a convinced believer in personal immortality, or “immortalism,” as he preferred to call it. He believed that all men and women have within them the possibility of eternal development; those whose souls develop day by day are “good” characters; those whose souls do not advance are “bad” characters. This is the fundamental distinction in his novels between folk who are admirable and folk who are not. In the fortieth chapter of Joseph Vance—a chapter that we ought to read over and over again—we find a sentence that, although spoken by one of the characters, reflects faithfully the philosophy of William De Morgan, who believed, with all his strength, in God the Father Almighty and in the Life Everlasting: “The highest good is the growth of the Soul, and the greatest man is he who rejoices most in great fulfilments of the will of God.”

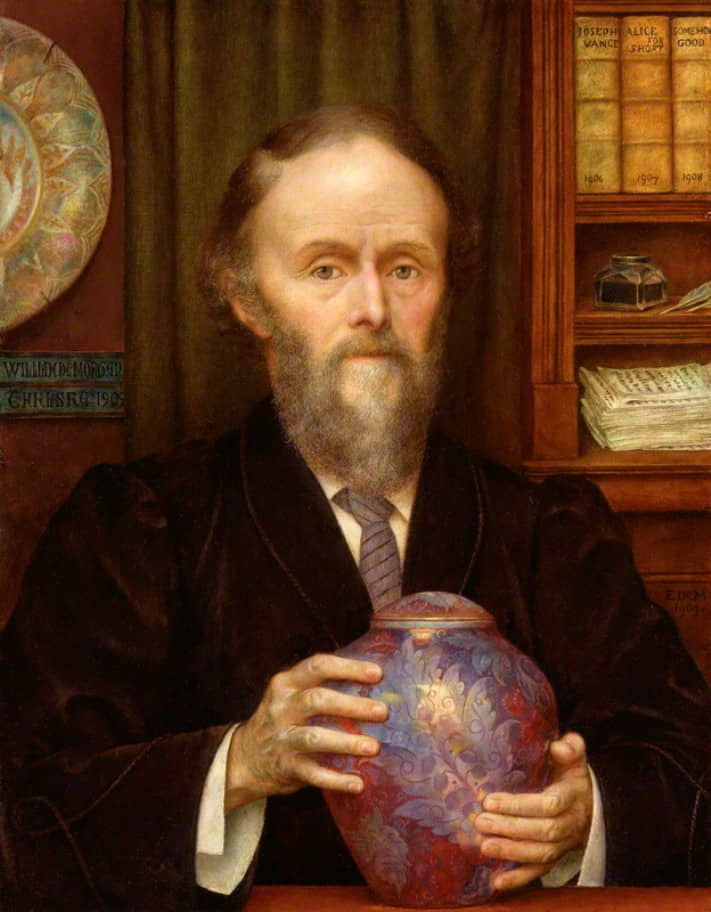

Featured: “William De Morgan,” by Evelyn De Morgan; painted in 1909.