Why is it difficult to consider the history of al-Andalus simply as a part of the history of the classical Islamic world, conditioned, to an extent that remains to be established, by its geographical and human context? Why is it common to interpret it, in a singularly acritical way, with the eyes of the present? This history has sometimes been presented as the prefiguration of a recovered national identity, as the prehistory of Hispanic consciousness, or as the “lost paradise of al-Andalus,” the “chronotope” of a lost identity, and an exile shared, from a different point of view, of course, by the Muslim world under colonial rule in the first half of the 20th century – which was undergoing the occupation of Palestine and the forced exodus of its Arab population – and by the Jewish intelligentsia of the 19th and 20th centuries, up to the birth of the State of Israel and even afterwards when Arab authors, after 1948, used it for propaganda purposes, until it became a commonplace denunciation of Israel.

In the following pages, I will examine how some contemporary American scholars have taken up all of these mythologies, inspired by nationalist sentiment, to make al-Andalus the Utopia of tolerant Convivencia (“coexistence”), the conduit of the fluid transmission of cultural and artistic motifs between the Arab and European worlds, the symbol of a beneficent globalization that opposes the petty localisms of national identities. I will consider the period I know best, that is, the political and intellectual history of the Andalusian emirates and caliphates, up to the end of the Taifa period, because it is quite possible – and I do not assert it – that it is different for other eras.

This idealized image goes hand-in-hand with a lack of knowledge of the milieu and the day-to-day, political, and social history of al-Andalus, of intellectual and religious figures and movements, of primary and secondary sources in languages other than English. From this situation comes the fact, for example, that studies of classical Arab-Islamic historiography, both older and newer, have neglected the work of Ibn Ḥayyān, as does Roger Allen’s recent history of Arabic literature – in the broadest sense; or that ʿAbd Allāh Ibn Buluggīn’s magnificent Memoir remains unrecognized and underutilized by North American scholars. While in the latter case the language barrier cannot be put forward – the primary translation being Tibi’s English translation – the argument of linguistic ignorance seems to hold elsewhere (with Anglo-American scholars often having little familiarity with French and Spanish bibliography).

Insufficient knowledge of Andalusian history and sources has reinforced the idea that al-Andalus was on the margins of the medieval Islamic world; and this has undoubtedly contributed to its idealization, making al-Andalus a tabula rasa on which to represent a number of more-or-less fictional narratives, the arena of ideological stakes derived from local academic discourse. Even a sensitive and attentive specialist like Julie Meisami affirms that “The Arabic literatures of Medieval Spain and Sicily do not occupy an important position in Arabic studies,” because they seem “peripheral to the tradition as a whole.”

The most influential of these narratives idealize the Convivencia of the three cultures – Arab, Christian and Jewish – in al-Andalus, during the period I have indicated, as well as the essential influence of the Andalusian civilization on the rise of European culture and its multiculturalism ante litteram. The apparatus of argumentation supporting these theses derives essentially from the antihistorical and anti-philological attitude advocated by the American postmodernist school, reinforced by the bellicose dialectic and axioms coming from the “postcolonial” studies launched after Edward Said’s famous denunciation of European Orientalism. The best-known representative of this trend, as far as al-Andalus is concerned, was [the late] María Rosa Menocal, Sterling Professor of Spanish Studies at Yale University.

The preliminary argument put forward by Menocal, in a posthumous polemic with the European Arabist school of the 20th century, is that the “Semitic” influence on medieval European culture has not been given the importance it deserves; not because it was difficult to prove this influence, according to an approach recognized by the academic community, but because of a bias, taken by this same school, which refused to recognize it in the name of a “myth of Western-ness,” of a colonialist mentality denying the obvious impact of the Arab-Islamic and Jewish civilizations on Europe. As in the famous quarrel between Américo Castro and Claudio Sánchez Albornoz, the central point of this opposition is not so much a question of method – how to prove the impact of the Arab literature of al-Andalus on the rise of European literature – but rather an ideological bias; the denunciation of the negative prejudice that has, until now, prevented this recognition.

Against the Eurocentric thesis attributed to the orientalist party defending identity politics, Menocal takes inspiration, in a generic and not very precise way, from the approach of Américo Castro to project onto the Iberian past a hypothesis of linguistic and cultural hybridization centered on the themes of “miscegenation” and “transculturation” in vogue among contemporary North American historians. There is, for example, the line of research by the dean of American modernist historians, Natalie Zemon Davis, on cultural “métissage” as a positive value, against the reductio ad unum of national identities – and its personification in the biography of Leo Africanus (Trickster Travels)

As for the general theory, one finds in it, sometimes deformed to the point of being unrecognizable, ideas that had often circulated, before being abandoned, within Orientalist scholarship itself, which itself is put on trial. The exaltation of tolerance and Convivencia derives from the belief in a golden age of Hebrew culture in Spain and in the myth of the Utopia of three faiths (the myth of interfaith Utopia), circulating among European Jewish intellectuals in the 19th and 20th centuries, as Mark Cohen has shown. While using the same arguments, and often the same examples, Menocal is nonetheless indifferent to the religious content of this conception – for not only does it deny the priority of the religious fact in the Middle Ages, but it also clearly disjoins what is “Arab” from what is “Islamic,” since both factors can hinder the cultural transmission between the Christian, Jewish and Islamic worlds. On several other points, which have been discussed at length without finding a solution, she makes sharp and peremptory judgments.

For example, “In Spain… Arabic was the lingua franca of the educated classes of the three religions, for several centuries.” A happy coincidence from which she launches her assumption that the Provençal word trobador “in fact has a perfectly plausible Arabic etymon, perhaps two,” an argument she considers definitive, but which, because of the hostility of the Eurocentric party, is supposedly not accepted. On issues that have proven to be unprovable, the logical leap is even bolder. This is particularly true of the vexata quaestio of the origins of the Divina Commedia for which she suggested that Dante may have read one of the translations of the Miʿrāj done when Brunetto Latini – the maestro and guardian of Dante – was in Toledo. The same the becomes true of the origins of the Divina Commedia.

The same then becomes true for the origins of Provençal poetry – the hybridization that would be at the root of the great season of courtly love would not have required knowledge of Arabic texts on the part of the troubadours, for they were “a bit more like rockstars than like scholars,” and that this knowledge was in the air. In fact, the so-called “Arabic thesis” concerning the birth of Romance literature had enjoyed a certain popularity, as Menocal reminds us, until the beginning of the 20th century – and this since the 16th century – only to be abandoned afterwards. The cause of this change of perspective appears in the rise of European colonialist imperialism, with its contempt for the cultures of dominated peoples, the Arabs in particular, coupled with the rise of the German philological method.

It is characteristic of the postmodernist approach to history to interpret events rooted in complex causes through conspiracy theories, deriving from the conception of a “master narrative” that organizes the whole of historical traditions, suppressing, at the same time, minority discourses. The master narrative of European orientalism and philology, the offspring of modern imperialism, follows the oblivion of the cultural contamination between the Judeo-Arabic and Romanic worlds, the memory of which was “purposely annihilated” when, during the 16th century, the Inquisition [she says] destroyed the great Arab libraries that represented the precious heritage of the three cultures.

This would have taken place in particular in Toledo, a city which, according to Menocal (and in contradiction to Jean-Pierre Molénat’s research on the real persistence of the Arab and Mozarabic communities in the new Castilian capital), would have hosted an enlightened cenacle of intellectuals, alien to ethnic prejudices, “a legendary mix of Christians, Jews and Muslims” at the center of a European network of scholars who competed for any work written in Arabic.

The transmission of the Judeo-Arabic heritage, as well as that of Arab-Andalusian lyricism (the minority discourse in the context of the Castilian conquest), would thus have become one of the best-kept secrets in the history of civilizations, having been interrupted by catastrophic events, such as the expulsion of the Jews from the Iberian Peninsula.

This rupture – coinciding significantly with August 2, 1492, the date of Columbus’ departure, the last medieval hero, for the Indies – was imposed by the proto-imperialist design of the rulers of Castile-Aragon. Definitively expelled from the medieval paradise – tolerating linguistic diversity and ethnic hybridization – the Spanish population and culture (for we are talking only about Spain) was then condemned to the obscurantism of the Enlightenment and to the hell of modernity. A modernity that discriminates between languages and diverse knowledge, introduces objectivity in sciences, generates the philological method (that atomizes and mutilates the unity of the literary phenomenon, demanding “proof of written texts” in order to justify its transmission) and the diachronic approach, “the most arbitrary and meaningless of ordering principles.” The discovery of the paths of this heritage is, on the other hand, made possible, in the absence of recognizable chains of transmission, by the post-modernist method that makes the “citationism” of rock music a true paradigm, ex post, of the medieval poetic approach, offering an obvious and convenient solution to the enigmas of intercultural transmission.

The opposition established between the Middle Ages and the modern era summarizes antinomies, which we have just seen: miscegenation/ discrimination, tolerance/intolerance, conquest/Convivencia. Similarly, the negative pole of philology is matched by the positive pole of lyricism in the strict sense – the “impure” lyricism of the muwaššaḥāt, whose descent from the classical tradition is ignored – and in the broader sense – post-modernist hermeneutics, steeped in musical and poetic references. This allows Menocal to argue – a daring anachronism – that “the medieval culture was postmodern” (because both periods shared the same feeling of distrust towards master narratives); or, conversely, that “the Reconquista… was anti-medieval,” because it reduced ad unum the cultural multiplicity of al-Andalus; and finally, to put forward the proposal of “telling History in the lyric mode,” this mode being that of the muwaššaḥāt, considered as the symbolic form of medieval cultural mixing.

Providing literal proof of T. F. Glick’s objective observation that “history seems scarcely distinguishable from myth,” history based on written sources and taken in a diachronic dimension gives way to fabled-seeming narratives, such as the one that opens Menocal’s more recent work, describing the arrival of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān, the archetypal hero of that saga of fruitful miscegenation that would have been al-Andalus: “Once upon a time in the mid-eighth century, an intrepid young man named Abd al-Rahman abandoned his home in Damascus, the Near Eastern heartland of Islam, and set out across the North African desert in search of a place of refuge…”

One certainly finds in this melodrama, with its misleading simplicity, all the themes and materials commonly used in academic works – however, its fable-like quality, which finds an enthusiastic echo in accounts in the popular press, and which draws on the medieval conception of history as memory and myth, nevertheless signals its defiant entry into a field where the formal structures of historical narration – diachrony and causality in particular – are no longer valid. Historical philology is not the only polemical target of the neo-Romantic myth of a tolerant, multiculturalist and lyrical Middle Ages. Prose is also negatively affected, because it is associated with the rational and discriminatory approach that modernity has imposed on knowledge, which has deprived Romance literature of its lyrical component.

This same penchant for binary oppositions had already manifested itself in Menocal’s first book, The Arabic Role in Medieval Literary Theory. A Forgotten Heritage, written in the mode of pre-post-modernist American scholarship; and, as such, reviewed by the major Arabist journals. It contains, among other things, the denunciation of the politics of denial of the “Semitic” heritage in European literary culture, which is the author’s trademark, and the attack on the claim of philological hermeneutics that intercultural contacts are mainly textual, or the result of a series of historically documented (“genetic”) relationships. This criticism, in itself legitimate and fruitful, is not accompanied by the proposal of an alternative hermeneutic, indebted, for example, to the sociology of literature or to sociolinguistics, or of establishing a new archaeology of literary transmission and the creation of mixed forms. It limits itself to presenting a self-referential instance, that of the subject who, by observing the synchrony and/or the geographical proximity of two similar phenomena, even in the absence of a certain contact or transmission, can only deduce that there has been something more than a “parallel development.”

Among the paradoxical and perhaps unforeseen consequences of the approach I have just described is the fictional and novelistic character of the resulting image of al-Andalus, an image from which any reference to material history, or even micro-history, is absent, and which is assembled from a few current literary sources – when, in principle, it should show the unexplored or secret paths of this transmission. It is understood that the medieval Andalusian paradise coincides with the Umayyad period and the century of the taifas, and that the Andalusian emirs and caliphs are attributed a conscious political project, based on the tolerance of languages and cultures. From this peaceful world of princes, poets, merchants and rabbis, not only the specifically Islamic character of al-Andalus disappeared, but also the Islamic and non-Arab components, and in particular the Berber component of society.

The Arab heritage, within the limits I have indicated, is thus fully integrated into the genealogy of European identity, but on condition that it is “Europeanized” and stripped of everything that differs from it; and this limitation of the inextricably Arab-Islamic character of al-Andalus inevitably leads, as Julie Meisami has noted, to a subsequent marginalization of Andalusian studies from the mainstream of Islamic studies. Isolated from the cultural context of belonging, literary texts, and especially lyric poetry, are interpreted as if they were the immediate expression of a pop culture shared across linguistic, cultural and material barriers. If it is true, as Meisami again observes, that this position aspires to overcome the aporia of the philological method – which distances the pleasure of the text as it subjects it to multiple dissections on the diachronic and synchronic axis – it is also true that it opens the way to the subjective projections of the critic and readers; that is to say to frankly anachronistic interpretations of the past.

This is evidenced by the insistence on the paradoxical nature of Andalusian culture, described as “taking pleasure in contradiction within one’s own identity,” since it is the “possibility of contradiction” that guarantees “true religious tolerance” and “cultural vitality;” or, again, the fact that it is considered a culture in exile, even “a summary of the varieties of exile that explicitly leaves ‘nations’ by the wayside.” Exile is, moreover, the precondition for poetic creation, and all of these thematic-contradictions (exile, tolerance, lyricism) are found together in the idealized portrait of ʿAbd al-Raḥmān I, a true figura, in both the classical and postmodern senses, of the Andalusian utopia, and arguably of the author. For, if the theme of exile descends in direct line from Said – and Auerbach before him – it grows with the set of psychological projections and mythographies linked to Menocal’s biography, which in turn seem to find more intense echoes in an immigrant society like that of North America.

And, while Romanticist philologists can legitimately be blamed for neglecting the “Arabic thesis,” out of ignorance of its cultural and linguistic context, the affinity of the poetic and figurative forms developed in al-Andalus, Sicily, Provence and Persia, could have suggested to the scholar (it is Meisami again who proposes this) the more complex hypothesis of a common tendency: “Of the vernacular literatures to free themselves from canonical modes of discourse in favor of others more responsive to their particular cultural ambience.”

The polygenetic thesis was adopted, in particular, towards the end of his all-too-brief existence, by Samuel Stern, a pioneer in the scientific study of the Mozarabic kharja, as recalled by the late Dorothée Metlitzki, in her erudite essay on the a similar subject which, characteristically enough, had no continuators.

The distortion that the image of al-Andalus underwent through its multiculturalist interpretation was received very favorably by the non-specialist public, as evidenced by the reviews in the popular press of The Ornament of the World. No reviewer shied away from embroidering on the world described by Menocal, a world supposedly created by the far-sighted design of Abd al-Raḥmān I, where the Convivencia of the three cultures gave rise to a literate and polyglot society, whose radiance lent light to early Europe which threatened its borders. A researcher like Fouad Ajami himself has not questioned the historical reality of this amiable utopia, which, in its sparkling perfection, seems to dispel the darkness of the post-9/11 era, offering “thought-provoking lessons for today.” The ambition to reform the present through the lessons of the past is explicitly acknowledged by Menocal, who began an op-ed The New York Times (eloquently titled, “A Golden Reign of Tolerance”) with the following statement: “The lessons of history, like the lessons of religion, sometimes neglect examples of tolerance.” She also titled a lecture at Yale Law School, “Culture in the Time of Tolerance: al-Andalus as a Model for Our Time.”

At the beginning of this essay, I mentioned how al-Andalus, in its idealized image, could represent the mirror of identity in which Spanish scholarship from the end of the nineteenth to the middle of the twentieth century prefigured the birth of the Spanish nation; its language and its culture, in opposition to the foreign and enemy-like Arab-Islamic entity. I also mentioned that the Arab culture, for similar and opposite reasons, erected al-Andalus as an “edifice for nostalgia,” a focus for the cult of a lost and coveted national primacy, which Jewish intellectuals in the diaspora saw as proof of a successful integration and as a counterpoint to the “maudlin conception of Jewish history” describing Christian oppression.

It thus becomes undoubtedly necessary to ask ourselves about the hidden agenda, that is, about the political motivations – in the broadest sense – implicit in the Andalusian mythographies elaborated by the American postmodernist school, and also about the reasons that can explain, more generally, the success of the image of al-Andalus as a “model for our time,” for the West in search of a new enlightenment. As for the latter, it is obvious that they owe much to the reassuring charm of the Andalusian melting pot, which, of course, knew, until the first three centuries of its history, neither the interethnic and intercultural conflicts that tore apart and still agitate, today, North American and European societies, nor the aggression of a hostile civilization. In the same way, by evoking the utopia of al-Andalus, one makes a negative judgment on Western modernity, which translates into a real political program, albeit largely abstract. For radical American intellectuals, as for Arab and Jewish intellectuals past and present, the Andalusian chronotope conjures up, in effect, “a sight of the present state of affairs, of colonialism, racism, sexism, political and intellectual repression, religious intolerance and militancy, class stratification and economic inequities that continue to plague the modern world.”

And, at the same time, al-Andalus calls for a hope of “social equality, economic progress, political liberation, religious tolerance and self-emancipation.” These two opposing visions feed the “countermyth” of the Andalusian Arcadia as a true ideal homeland forever lost: “A perfect place… where the religions of the children of Abraham all tolerate each other and where, in the peace of that tolerance, and in the shade and fragrance of the orange trees, we could all sit and talk about philosophy and poetry.”

This also explains, no doubt, why the only discordant voices in the chorus of Menocal’s supporters were those of intellectuals of the neo-conservative right, such as Robert Spencer, and above all Bat Ye’or, a polemicist of Egyptian origin and British nationality, who is very active on the North American scene as a spokesperson for the “countermyth” of the “neo-lachrymose conception of Jewish history,” referring to Jewish oppression in Islamic lands.

Beyond these general considerations, it is worth returning to the negative influence that this approach has had on Andalusian studies in the United States, as shown in the collective volume on the literature of al-Andalus, in the Cambridge History of Arabic Literature, of which Menocal was the editor. This book was intended to mark a clear break from the others that preceded it in the same series, which represented the culmination of the method of approaching texts that characterized post-war Western – and especially Anglo-American – Arabism. The introductory essay made it quite clear that this was a work with intentions, the main one of which was “cultivating the memory of al-Andalus,” which thus closely followed the aspiration of Arab and Jewish utopian nationalisms.

The revival of interest in al-Andalus is attributed neither to the process of recognizing and integrating the Arab-Islamic past into national history nor to the rise of academic studies – and those aimed at the general public – that have so profoundly changed the Spanish intellectual scene since the end of Francoism; but rather, vaguely, to “the explosion of international tourism” and the influence of writers as foreign to the Andalusian terrain as Salman Rushdie. The approach that is polemically taken is that of “cultivating the memory of al-Andalus.” The approach that is polemically announced does not aim at the interpretation, as exhaustive as possible, of the available historical and literary materials, but at the personal “vision” of the interpreters, which organizes and gives meaning to the subjects treated through an arbitrary game of inclusions and exclusions.

This methodological bias prescribes not only the treatment of non-Arabic literatures of al-Andalus (Mozarabic and Jewish, in particular) but also the maintenance of this tradition through, for example, the Jewish literature of the Balkans, the Near East and Morocco, after the diaspora of 1492, because, according to the author of this chapter, which is very interesting, it testifies to the famous tripartite culture which proves to be the main subject of this book. In the same way, and as an inverse corollary of the thesis of the inclusion of the Arabic tradition in the Romance tradition, it is accepted to deal with some authors born in Andalusian territory who knew Arabic, but whose surviving writings belong to the literary tradition in neo-Latin and the Romance languages. This is the case of Ramon Llull and Petrus Alphonsi, whose biographies stand alongside those of, among others, Ibn Quzmān, Ibn ʿArabī, and, curiously enough, Ibn al-Khaṭīb.

The emphasis on minority or peripheral traditions, in relation to the Arab-Islamic tradition, together with the denial of anything that would impede the thesis of uninterrupted circulation between the Arab and Christian worlds, intentionally obscures the Islamic character of literary production in Arabic. The Islamic sciences, religious as well as secular – all categories – are treated in some thirty pages of the chapter on “knowledge,” with vague and rhapsodic content, occasionally faulty. While the category of “literary text” manages to include artistic and architectural items, religious literature is virtually excluded from the literary forms (only mystical poetry is mentioned, under the heading of “Love,” with a few suggestive passages extracted from Ibn Ḥazm’s writings), as is the historiographical tradition.

More generally, the prose tradition and the Andalusian adab, in its varied forms, finds no formal definition – while poetry is given pride of place among the “forms of literature” (“Qasida” and “Muwashshaha“), thematic sections (“Love”), and biographical sketches of the authors, the very rich production of rasā’il (epistles) receives no special attention, and the maqāmāt are mostly considered within the framework of the Jewish literature of al-Andalus. Similarly, to conclude the list of what one expected to find – or not find – in a work devoted to the literature of al-Andalus, one must mention the Berbers – they are hardly distinguished here as bearers of an autonomous tradition, not even in the section on “Marriages,” which reports on inter-Andalusian cultural hybridizations, while an entire section is generously allocated to the Arab-Sicilian literary tradition, again in the broad sense that allows for the inclusion of architectural monuments and authors belonging to the Norman and Swabian eras.

The result of this radical effort to redefine the Arab-Andalusian literary canon – which goes so far as to include Cervantes and his Quixote – ends up being paradoxical, in a sense that is certainly foreign to the manifesto stated in the Introduction, as well as alien to the postmodern spirit. By making the literature of al-Andalus the precursor of European literature, it ends up confirming the prejudices of the Franco-Spanish Andalusian school, when it distinguished, especially in the society of the taifas, the Arab and Berber groups from the “Andalusians,” to whom the great intellectuals considered proto-humanists supposedly belonged. One inevitably finds this distinction in the book, in the section of the “Andalusians,” eminent individuals chosen according to mixed and rather unconstrained criteria, and treated in a heterogeneous way.

Despite the uneven value of the contributions and its obvious limitations (which others have pointed out long before me), the volume on al-Andalus literature today represents an indispensable reference for young American scholars, to whom it offers a simplified method of approaching the texts and their history, which requires neither precise knowledge of the historical context nor extensive linguistic skills. This is demonstrated by Cynthia Robinson’s book, In Praise of Song, which borrows from Menocal’s most outrageous theories of cultural hybridization and is its main reference.

In this book, often suggestive and supported by a relatively extensive secondary bibliography (albeit with significant gaps), Robinson, a specialist in the Andalusian art of the taifas, argues convincingly for the substantial unity of the artistic and literary manifestations of the taifas around the phenomenon of the court. Less solid, on the other hand, is not only the analysis of the internal dynamics of the life of the Arab-Andalusian courts – interpreted, in a way as ingenious and abstract, as the hermetic drama of the Fedeli d’amore that would have been the mulëk (rulers) and their entourages – but above all the demonstration of the main thesis which claims that the transmission of poetic themes and forms between the two worlds was carried out, not at the popular level and through occasional contacts, but thanks to the relations, above all diplomatic, between the Andalusian and Christian courts from the fifth to the eleventh century.

Accepting without reservation Menocal’s two main methodological postulates – that differences in religion and language cannot be an obstacle to the transmission of cultural themes, and that al-Andalus is simply part of the “cultural heritage of medieval Europe” – Robinson is content to define the paths of this presumed transmission through the arguments of “context,” “contact” and “the demonstrable chronological precedence of the Andalusian model of courtly culture.” In doing so, and in this case also following the precedent set by Menocal, she not only disregards philological arguments (scansions, meter or linguistic points), but also seems to overlook a possible polygenetic interpretation, indicating that the analogies found derive from the system of relations and semiotics characterizing the court as a sociological space common to different civilizations, even if they are distant in time and space. Ignorance of a substantial part of the recent bibliography on al-Andalus – especially the onomastic and documentary series published by CSIC in Madrid – also leads Robinson to frequent errors in the names of personalities, while insufficient familiarity with Andalusian sources seems to be responsible for the few important interpretative errors.

Finally, a further effect of the subjectivism that characterizes this approach, which might be called neo-orientalist, seems to be the projection onto al-Andalus of a vaguely literary quest for exotic and fabulous themes. A striking example of this appeared on the English-language Arabist information list H-Mideast Medieval, where a request for information was formulated thus: “I am urgently seeking medieval references to al-Andalus as an exotic/erotic place. I have a theory from my reading of medieval Islamic maps of the Maghrib. I am looking to see if there is any textual support for my theory. Poetry seems to be the most likely place to find what I am looking for… but I am open to any and all suggestions, even those that come from architecture for possible references to al-Andalus as a place of Muslim fantasy.”

These statements summarize, in an almost parodic way, the approach that I have tried to describe: The formulation of a problem, more or less vague, leads to the search for documentary evidence of indeterminate value, which amounts, in most cases, to employing poetry as the hermeneutic tool of choice, which can legitimize any interpretation.

In conclusion, I asked myself why this approach, and the theoretical perspective that inspires it, have become the majority in the United States today, when other directions had been given to research on al-Andalus: I am thinking, for example, for the period and the arguments in question, of the works of Glick and Metlitzki, or of a few essays by Wolfhart Heinrichs and his student Beatrice Gruendler, Arabists from Harvard and Yale respectively, placing Andalusian authors and works in the Arab-Islamic synchronic context and in the tradition of akin genres, as well as of the two essays devoted by Salma Khadra Jayyusi to the literature of al-Andalus, in The Legacy of Al-Andalus.

In an article written nearly forty years years ago, Menocal called for an end to both the “segregation” of the Romance literatures of Arabic literature and the academic distinction between “Near-Eastern” and “European Studies.” Today, one has the impression that her example has allowed the realization of this wish along with the caveat stated by Meisami. While in Europe there is an effort to place the history and culture of al-Andalus in the mainstream of medieval Arab-Islamic history, in the United States al-Andalus appears today to be marginalized from the departments of Near Eastern Studies – invariably considered from the perspective of “hybridity” and “transculturation,” it is found mostly in the departments of Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies, or even Hispanic or Romance Studies.

This tendency is undoubtedly reinforced today, at the level of mass culture, by the importance of the theme of the dialogue – or clash – of civilizations, coupled with the preference given by the American cultural industry (as a pioneer of a trend that is also asserting itself in Europe) to simplistic messages on complex issues, and to immediate communicative and emotional impact. Finally, and to return to the question that opened these reflections, the transformation of al-Andalus into a normative model for a West that one would like to be less hegemonic, more tolerant of its own diversity, testifies to the persistent attraction that the Andalusian chronotope has on contemporary utopian nationalisms.

Bruna Soravia is an Italian scholar who studies Islamic Spain. This essay is excerpted from Manuela Marín, ed., Al-Andalus/España. Historiografías en contraste.

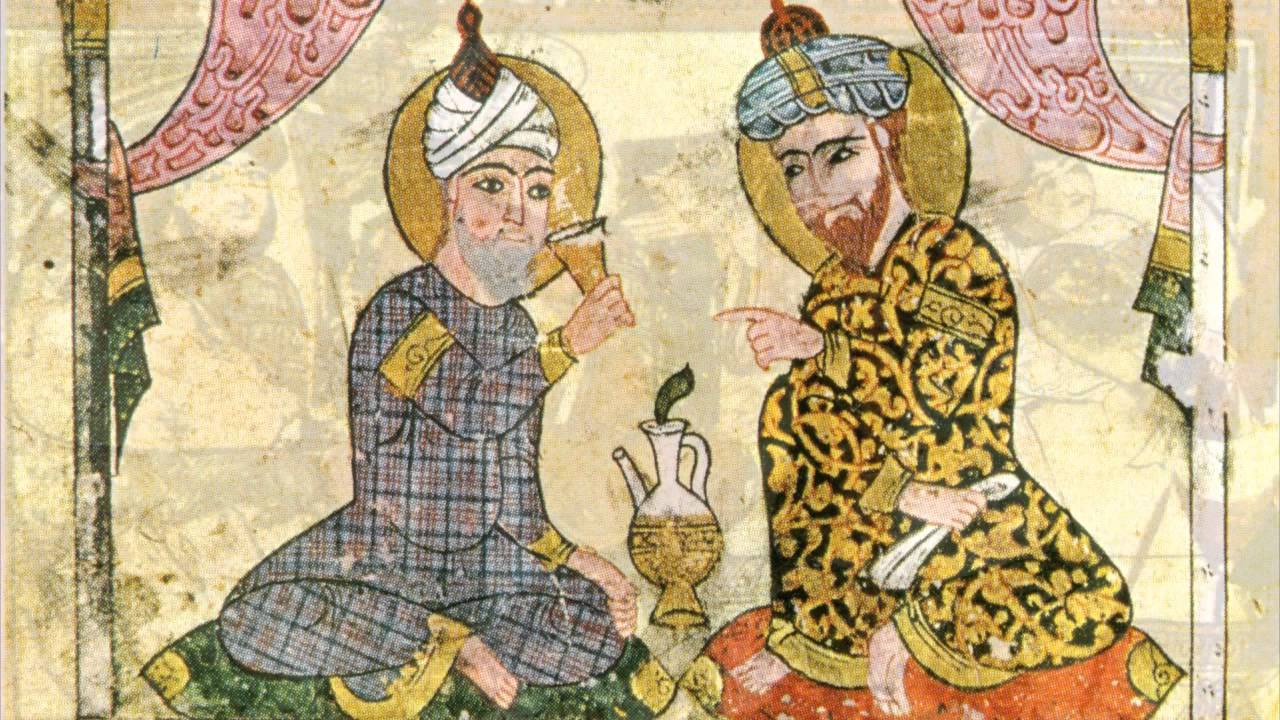

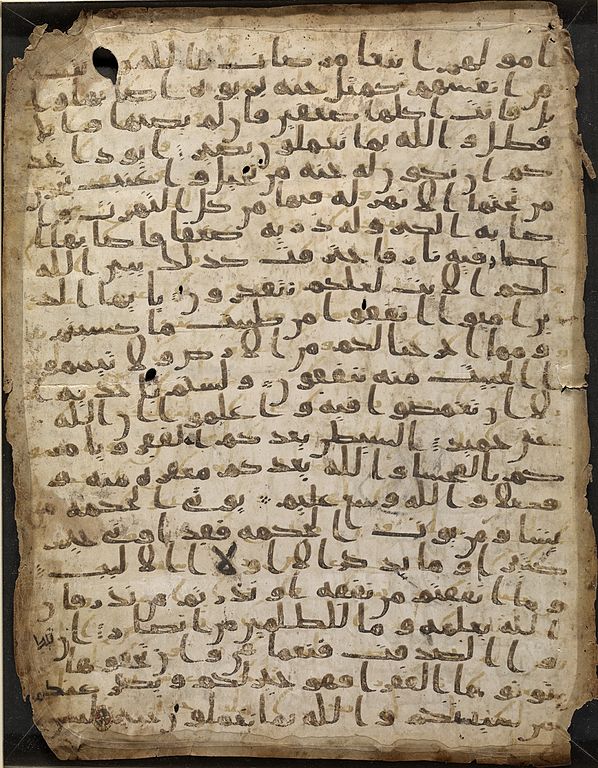

The featured image shows a leaf from the Maqamat of al-Hariri, Syria, 1237.