Contemporary German architecture set its main trends in the first thirty years of the 20th century. The strongest influences came from Weimar and Dessau, where the Bauhaus school was founded in 1919.

Under the leadership of Walter Gropius (1883-1969) and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886-1969), the Bauhaus style spread to the far corners of the earth. Today masterpieces of its synthesis of architecture, technology and functionality can be found all over the world.

One of the main goals of Bauhaus was to renew architecture. The leaders of Bauhaus, Walter Gropius, Hannes Meyer, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, were architects.

The origins of Bauhaus were far from the earlier methods of education in industrial art, art proper and architecture. Its program was based on the newest knowledge in pedagogy.

The idealistic basis of Bauhaus was a socially orientated program, wherein an artist must be conscious of his social responsibility to the community, while the community has to accept the artist and support him. The word, “Bauhaus” is from two German words, Bau, or “building” (from the verb, bauen, “to build”), and Haus, or “house.” The literal meaning is, “architecture house.”

But above all the intention of Bauhaus was to develop creative minds for architecture and industry and thus influence them so that they would be able to produce artistically, technically and practically balanced utensils.

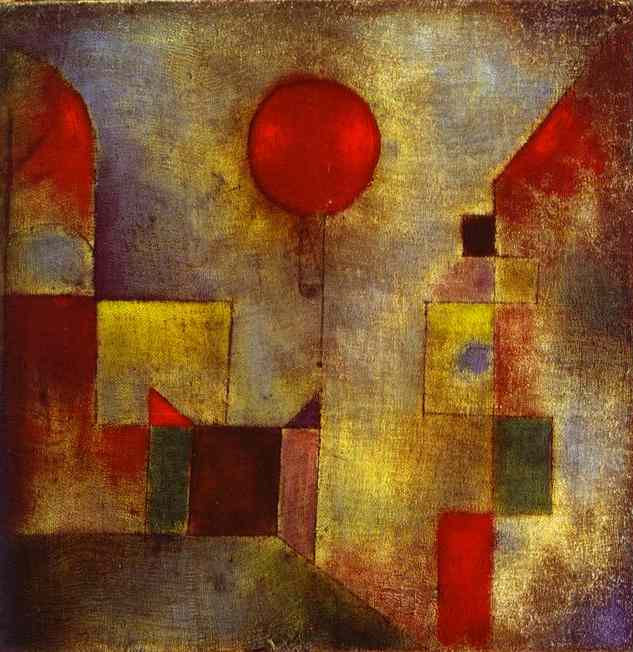

The institute included workshops for making models of type houses and all kinds of utensils, and departments of advertising art, stage planning, photography, and typography. The neoplastic and constructive movements of art to a great extent steered the form lines of Bauhaus. Teachers were such masters of modern art as Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee.

To better understand the aims of the Bauhaus school, one has to read the following extracts from Walter Gropius’ Manifesto: “The ultimate aim of all creative activity is a building! The decoration of buildings was once the noblest function of fine arts, and fine arts were indispensable to great architecture.

Today they exist in complacent isolation, and can only be rescued by the conscious co-operation and collaboration of all craftsmen. Architects, painters, and sculptors must once again come to know and comprehend the composite character of a building, both as an entity and in terms of its various parts. Then their work will be filled with that true architectonic spirit which, as “salon art”, it has lost.” … “Architects, painters, sculptors, we must all return to crafts! For there is no such thing as “professional art”.

There is no essential difference between the artist and the craftsman. The artist is an exalted craftsman.” … “Let us therefore create a new guild of craftsmen without the class-distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsmen and artists! Let us desire, conceive, and create the new building of the future together. It will combine architecture, sculpture, and painting in a single form.”

Often associated with being anti-industrial, the Arts and Crafts Movement had dominated the field before the start of the Bauhaus in 1919. The Bauhaus’ focus was to merge design with industry, providing well designed products for the many.

The basic idea of the Bauhaus teaching concept was the unity of artistic and practical tuition. Every student had to complete a compulsory preliminary course, after which he or she had to enter a workshop of his or her choice. There were several types of workshops available: metal, wood sculpture, glass painting, weaving, pottery, furniture, cabinet making, three-dimensional work, typography, wall painting, and some others.

It was not easy to get general allowances for the new type of art education. A political pressure was felt from the beginning. In 1925 the Thueringer government withdrew its economic support from the education. Bauhaus found a new location in Dessau. The city gave Gropius building projects: a school, workshop and atelier building (1925-1926) has remained in history by the name ‘Bauhaus Dessau’.

In October 1926, the school was officially accredited by the government of the Land, and the masters were promoted to professors. Hence, the Bauhaus obtained the subtitle “School of Design”.

The training course from then on corresponded to university studies and led to a Bauhaus Diploma. Later this year, because of some political and financial difficulties, the Bauhaus center could no longer remain in Weimar and was closed. In April 1925, Bauhaus resumed its work in Dessau.

Personal relations in Bauhaus were not as harmonious as they may seem now, half a century later. The Swiss painter Johannes Itten and the Hungarian Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, who taught the Preliminary Course, left after strong disagreements in 1928, Paul Klee – in 1931. Some, for instance Kandinsky and Albers, stayed loyal until the closing of Bauhaus in 1933.

In spite of the success, Gropius left the Bauhaus leadership in 1928. His successor was the Swiss architect Hannes Meyer. He promoted the scientific development of the design training with vigor. However, Meyer failed as leader due to political disagreement inside Bauhaus. He was dismissed in 1930.

The German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe was invited as director. He was compelled to cut down on the educational program. Practical work was reduced. Bauhaus approached a type of ‘vocational university’. It began to loose the splendid universality that had made it so excellent. Training of vocational subjects started to dominate the initial steps of education. As a matter of fact this tendency became stronger after Mies van der Rohe had transformed the school into a private institute in Berlin in 1932.

The Nazi majority of Dessau suspended the seat of learning. Paul Schultze-Naumburg was the architect that they sent into the school to re-establish pure German art instead of the “cosmopolitan rubbish” the Bauhaus artists were doing. He described Bauhaus furniture as Kisten, or boxes.

Bauhaus was even as private institution so much hated by the National Socialist government that the police closed it up on 11th April, 1933. By September 1932, the Nazis had won a majority in Dessau, and cut off all financial support to the Bauhaus. The school was forced to move to Berlin, where it survived without any public funding for a brief time. On April 11 1933, the Berlin police, acting on the orders of the new Nazi government finally closed it.

The Nazi’s “degenerate art” exhibition in 1937 featured works by several former Bauhaus teachers. The Nazis failed in their efforts to completely erase the Bauhaus.

Its forced closure and the subsequent emigration of many of its former staff and students, ensured that it would become famous and influential throughout the world, especially in the United States, where a Bauhaus school was established in Chicago in 1937. The Bauhaus had a lasting impact on art education and in architecture.

The New Bauhaus, founded in 1937 in Chicago, was the immediate successor to the Bauhaus dissolved in 1933 under National Socialist pressure.

Bauhaus ideology had a strong impact throughout America, but it was only at the New Bauhaus that the complete curriculum as developed under Walter Gropius in Weimar and Dessau was adopted and further developed.

The former Bauhaus master Laszlo Moholy-Nagy was founding director of the New Bauhaus. The focus on natural and human sciences was increased, and photography grew to play a more prominent role at the school in Chicago than it had done in Germany. Training in mechanical techniques was more sophisticated than it had been in Germany.

The method and aim of the school were likewise adapted to American requirements. Moholy-Nagy’s successor at the head of the Institute of Design, Serge Chermayeff, however, remained still quite true to the original Bauhaus.

In the 1950s the New Bauhaus merged with the Illinois Institute of Technology. The Institute of Design is even now still part of the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago, and rates as a respected and professionally oriented school of design.

Courtesy of German Culture.

The photo shows, “The Red Balloon,” by Paul Klee, painted in 1922.