Christian scholarship is rare in the context of current university disciplines. Strong is the myth that the basic tenets of the Christian faith belong to that “childish” phase of human history when people were credulous and superstitious, lorded over by a cruel, avaricious church that used ignorance and violence as a means of control. The go-to reference for all this imagined savage theocracy is the medieval era. This myth is deep-seated in the Western mind (thanks to the Protestant Black Legend) – and, despite many worthy efforts, it remains well-entrenched. Myths serve many purposes. This one reifies progressivism, which is the religion of modernity.

But there was also a time when unchristian scholarship was unimaginable, because the life of the mind was aligned with eternity. The abandonment of eternity by academia (the greatest tragedy) unmoored learning from its historical mission – which was to provide an eternal purpose to life by way of reason. This was once called the life of the mind. Education has now begun its Wandering in the Desert.

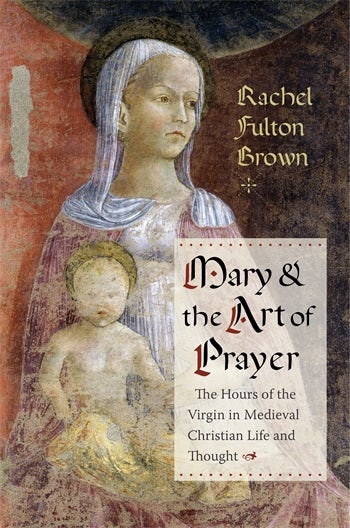

In all this aridity, it is refreshing to find a spring of Christian scholarship yet living, in the form of a learned and profound book. This is Rachel Fulton Brown’s Mary and the Art of Prayer. The Hours of the Virgin in Medieval Christian Life and Thought. Given that this book is deeply Christian and rigorously scholarly, its reception will be problematic. Some may find in it a heuristic for recouping the feminine in the medieval past, in the person of the Virgin Mary. Others will quibble about this or that source material, or even the exclusion or inclusion of this or that scholar. And, the sad Protestant-Roman Catholic divide will continue to use Mary to mark out difference. Indeed, the Virgin is unimaginable for Protestants once Christmas is over; while for Roman Catholics and the Orthodox, Christianity itself is unimaginable without her. If truth is the goal of scholarship, then scholarship had better first know what truth actually is. Any sort of materialistic construct is incapable of truth, because all it can do is demonstrate cause and effect (fact). This is only the first step, because the fullness of truth also needs purpose. The question, “Why?” needs an answer. Once facts find their purpose, truth is at last obtained.

Fulton Brown offers truth, by successfully tearing away the façade of causes (i.e., feminism) that now distorts so much of education and offering instead eternity. Thus, her book is highly contentious and highly important, and consequently, it will be ignored, dismissed, criticized, found wanting, and even declared to be not scholarly at all. Regardless, the life of the mind runs deeper than the shallow advocacies of professional educators. This is why the majority of academic writing is worthy only for obscure journals that nobody reads. In contrast, Fulton Brown’s book is careful, meticulous, profound, deeply learned – and accessible – and it must be read by all those interested in the history of big ideas.

The book is best described as a meticulously woven tapestry of medieval faith, spiritual discipline, history and natural theology, whereby medieval Christians sought completion (or harmony, as Plato and even Aristotle understood it) – which was the instantiation of divine grace in creation. To cultivate the mind meant leading the soul to salvation.

Fulton Brown demonstrates this process adroitly. Her premise is unique and intriguing – that the Virgin Mary was the dynamic of early and medieval Christianity, in whom meaning itself was determined: “…Mary was the mirror of the Divinity; she was the model of mystical illumination and the vision of God, the Queen of the Angels and the Mother God, as like to her Son as it is possible for a creature to be, enthroned beside him in heaven and absorbed in the contemplation of the Divine.”

Thus, Mary was not some incidental figure thrown in beside the manger and then at the foot of the cross – but that she was the very “logic” of Christianity – for how is the Word (Logos) to be made flesh, if not through the womb? And, therefore, unlike any other human being, Mary also must fulfill the law and the prophets, like her Son. As Rachel Brown brilliantly demonstrates, this summation is not some medieval fantasy, dreamt up by monks, who needed to come up with a “Christianish” figure to replace the supposed “wide-spread cult” of the “Mother Goddess” (this academic fantasy, an invention of Marija Gimbutas, has finally been debunked). Instead, devotion to Mary is as old as Christianity itself – and, like Jesus, Mary’s presence in the Old Testament was widely known, acknowledged and understood, that is, until the Reformation brought on historical amnesia (the blinkers of sola scriptura).

To show the antiquity of Marian devotion, Fulton Brown uses Margaret Barker’s Temple Theology that has uncovered continuity from Judaism to early Christian piety. This, of course, follows Christ’s direction on the Road to Emmaus (Luke 24: 25-27). Therefore, the Virgin is the Ark of the Covenant, the Tree of Life, Zion, the Burning Bush, Jacob’s Ladder, the Temple and the Tabernacle, the Holy of Holies, the Holy Wisdom, the Object of the Song of Songs, the Chalice, the True Bread of Heaven, the Rod of Jesse, the Gate of Ezekiel, the Lily of the Valley, and so forth. In short, all those descriptions whereby God allows human access to Himself. It was Albertus Magnus who carefully traced the many references to Mary in the Old and New Testaments, in his classic work, the Biblia Mariana.

But how do we know that this is not some invention of Albertus Magnus, or some other monk? How do we know that devotion to Mary has always been at the heart of early Christianity? Very simply, because the first church at Jerusalem venerated the Virgin (per Dom Thierry Maertens, who has studied this subject extensively). This veneration is present in the two credal confessions – that of the First Ecumenical Council at Nicaea in 325 AD, and then that of the Third Ecumenical Council at Ephesus in 431 AD, in which Mary was recognized as the Theotokos, the “God-Bearer,” or the “Mother of God.” As Rachel Brown observes: “She was the one who made the Lord visible to the world, clothing him with flesh as he passed through the veil, magnifying his glory as he came forth from the womb. Mary was the one who, harmonizing heaven and earth, scripture and human understanding, made it possible to discern God.”

Thus, medieval Christianity was neither a perversion nor a corruption of some “pure,” first-century Christianity (as the Reformers always imagined, without any historical evidence). It is also often assumed that Saint Paul’s epistles say nothing about Mary. But even this is not true, since the epistles do not deny the virgin birth of Jesus; and Paul does write that deeply Marian passage in Galatians 4:4-6, in which the entire mystery of God becoming man is summarized, a process in which Mary is essential.

In effect, the medieval veneration of Mary had an ancient precedent in Marian devotion in Jerusalem. There is no early Church, nor early Christianity, without Mary – because Mary was the “Mother of the Word,” as Fulton Brown aptly observes. Whether medieval men and women were aware of this antiquity is immaterial. For example, the core vocabulary of the English language goes back to the Bronze Age (and perhaps even earlier); and English-speakers are largely ignorant of this antiquity. But such unfamiliarity takes nothing away from the actual history of the English language.

For those who might imagine that medieval Christianity has nothing to do with the first-century Church, an appeal to basic logic would be necessary. First, the faith itself depends upon events which are all based in the first-century. Second, the epistles of Saint Paul go back to within a few decades of Jesus Himself, and they contain various pre-Pauline creeds and hymns that come from within a few years after Jesus’ death and resurrection. Thus, for those trying to prove disjunction as “normal” in history would need to disprove the first-century context in all of the New Testament – which was the very same Scripture that the faithful read in the Middle Ages. Therefore, how could medieval Christians not help being part of first-century confessional reality? Again, it matters not at all whether they knew their faith to be first-century (and earlier).

But to be fair, when the medieval mind imagined the world of Christ, it did so through the lens of Romanitas (Romanity, Romanness). Therefore, it is wrong to think that medieval awareness was unhistorical, or even a-historical. The remarkable thing about Christianity is its unbroken continuity with its origins in the first century. This sets it apart from all other religions (including even Judaism). The medieval world understood this very clearly.

One piece of evidence of this understanding is the use of exempla (historical anecdotes), which divide time into three distinct categories – diachronic time, retrospective time and eternal time. Historical past, including the era of Jesus, was diachronic. Of course, the tradition of using exempla is Classical (ancient) in origin, which medieval philosophy knew. As well, we should not forget the fact that the calendar evidenced how long ago Jesus lived, since it was (and is still) based on His birthday. This means that the medieval world did know that Jesus lived in the first-century, and they did know that the New Testament came from that time period, with the Old Testament being earlier. This means, then, that the medieval world knew that Christianity possessed historical continuity.

The Virgin, therefore, was always crucial to the life of the Church, because she fulfilled the great hope of humanity by bringing the Savior into the world – she is the starting point of mankind’s salvation. Devotion to her is not a denial of Christ (an either/or proposition is simply a confused epistemology) – but it is an affirmation of God’s salvific plan in Jesus. How? By making the mystery of the Incarnation into a Mother-and-Child relationship. When God is born as the Baby Jesus, He must also take on Mary’s flesh. And in doing so, her flesh, her humanity, merges with the Divine, which is Jesus’ dual nature (God and man). What better example of salvation can there? God made flesh so that humanity can become God-like.

Thus, to assume, as all Protestants do, that Mary just became a regular housewife once Jesus got born and had other children by Joseph, is to misconstrue, and then cast doubt on, the Incarnation – which must be a unique event, a “process” brought about by a unique human being (Mary). Otherwise, Jesus is just a man, the physical son of Joseph, because Mary’s womb was not special and was not meant for only one purpose (giving birth to God as man). When Mary is touched by God in such an intimate way, can she just simply go back to “normal” when what she has done is not “normal?” It can even be said that the denial of Mary brings in the eventual death of theology (which is the condition of present-day Christianity, which now seeks to exist beyond theology). Without Mary, the only thing left is a fatigued reliance on allegory, which is a polite way of saying, “superstition.”

But Fulton Brown’s book is not only about the Virgin in the Middle Ages; it is also a significant study of a discipline long-forgotten in the modern world – that of prayer. Indeed, prayer is an intensely human expression, being found in all of human history. But what sets apart Christian prayer? Two things. First, it is “paying attention to God;” it is an “engine…for lifting the mind to God.” Second, as Tertullian reminds us, prayer is sacrifice. For the medieval Christian, prayer was intense meditation and sacrificial offering, affected through intense discipline.

This discipline consisted of reading, memorizing, and repeating set prayers, or litanies, and Fulton Brown focuses on one such litany, the Hours of the Virgin (the Little Office of the Virgin Mary). The term, “litany” derives from the Greek litaneia, which means “prayer,” or “supplication” and involves a schedule of biblical passages, hymns and set prayers to be recited throughout the day. Constant attention, constant sacrifice to God, such were the ideal objects of medieval piety. The discipline came in two forms. First, the daily recitation itself of the various passages, hymns, prayers and petitions; second, the memorization of large portions of the Bible, such as, all the Psalms. Thus, a life of the mind forever attached to God, and each hour of the day and parts of the night spent in His service. This rigor has long vanished from daily life – not that every medieval individual undertook this rigor either – but it was the ideal and everyone pursued it to the best of his ability. This ideal has now vanished.

In an effort to bring back this rigor, this discipline, Fulton Brown guides the reader along in practicing a medieval litany. The very idea of spending hours at prayer is now foreign, given the fact that for most Christians an hour every Sunday seems sufficient. And the object of medieval prayer? Mary, who was the “engine” that lifted the mind and the soul to God: “A creature herself, Mary reflected the virtues and beauty of all God’s creatures; and yet, she had carried within her womb ‘he whom the world could not contain.’ This was the mystery evoked at every recitation of the angel’s words: ‘Dominus tecum’ (the Lord is with thee)’… She it was whom God filled with himself.” In effect, Mary was the engine that made Christianity work, for without her, the Incarnation is denied.

It must be said that Fulton Brown uses a vast array of source material in her study. Such marshaling of material is indeed rare today in academia (given the plague of specialization) and deserves praise. She provides her two subjects (Mary and prayer) a thorough context in medieval theology, philosophy, literature, art, music, and history, by way of some 265 original sources, which range from Adamus Scotus to Guibert de Nogent to José Ximénez de Samaniego. All of these sources bolster the thesis of the book – the centrality of Mary to early and medieval Christianity.

More importantly still, Fulton Brown provides a systematic experience of what Christian faith was really like in the Middle Ages. Thus, reading this book is to undertake an intense training, not only in medieval piety – but in the earliest aspect of Christianity, which was rooted in devotion to Mary: “…the one who made the Lord visible to the world, clothing with flesh as he passed though the veil, magnifying his glory as he came froth from the womb. Mary was the one harmonizing heaven and earth, scripture and human understanding, made it possible to discern God.”

Mary and the Art of Prayer is a book that must be on the shelf of every thoughtful Christian who wishes to understand the quality and the nature of his faith – and it must be read by those who wish to understand the importance and urgency of prayer – for piety without good works (prayer) is selfishness.

Fulton Brown concludes her book with an analysis of Maria de Jésus de Agreda’s (or, Sor Maria) Mystica ciudad de Dios (The Mystical City of God), which is a life of the Virgin that was published in 1670. In it, Sor Maria offers this insight: “…for into the heart and mind of our Princess [the Virgin] was emptied and exhausted the ocean of the Divinity, which the sins and the evil dispositions of the creatures has confined, repressed and circumscribed.”

Such “dispositions” are with us still – so much so that the Church today only wants to be “relevant,” because it can no longer make people holy, let alone make them Christian. The Church has abandoned its flock, which now wanders about unshepherded, seeking God in so many false pastures. Perhaps, therefore, Fulton Brown’s book has appeared at the right time, for the world is in sore need of the discipline of prayer, so that it can restart the Engine of Christianity, without which humanity is lost. This Restart will first mean the reestablishment of fidelity to the truth of Christian. Fulton Brown has offered a blueprint. Have we eyes to see?

The photo shows, “Speculum iustitiae” (The Mirror of Justice) by Giovanni Gasparro. He graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome in 2007, as a pupil of the painter Giuseppe Modica, with a thesis in art history on the Roman stay of Van Dyck. His first solo exhibition took place in Paris is in 2009, and in 2011, the Archdiocese of L’Aquila commissioned him to do nineteen works of art between altar and altarpiece for the thirteenth century Basilica of San Giuseppe Artigiano, damaged by the earthquake of 2009, which constitute the largest painting cycle of sacred art made in recent years. In 2013 he won the Bioethics Art Competition of UNESCO’s Bioethics and Human Rights Chair with Casti Connubii, a work inspired by Pope Pius XI’s 1930 encyclical. He exhibited at the 54th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, curated by Vittorio Sgarbi and at the National Gallery of Cosenza in comparison with Mattia Preti, the Pinacoteca Nazionale of Bologna, the Palazzo Venezia in Rome, the Alinari Museum of Florence, the Napoleonic Museum of Rome, and the Grand Palais of Paris, among many other venues.