Called back to God on December 31, 2022, Pope Benedict XVI built a singular theological work, confronting the intellectual issues of his time with a pastoral concern that thwarts any academic reduction. The Bavarian theologian who, as his spiritual testament made public on the day of his death testifies, worked until the end of his life for the emergence of “the reasonableness of faith,” has laid the groundwork, notably with his trilogy Jesus of Nazareth and his introduction to Christianity, The Faith and the Future, of a Christocentric theology, leaning on the great theological tradition and oriented towards the mystery of the cross, where divine revelation is completed and finalized.

The concern for pedagogy combined with the demand for coherence characterizes Joseph Ratzinger’s intellectual and spiritual approach in the three volumes of Jesus of Nazareth and offers the luxury of being able to reveal from the outset, without the risk of misunderstanding, the insight that animates the theologian throughout this article. This intuition, born of meditation on the Gospels and reading the Fathers of the Church, is expressed several times by Ratzinger and can be summarized as follows: Jesus Christ, before bringing a message, a kingdom or a long-awaited pax, brought God. “He brought the God whose face was slowly and progressively revealed from Abraham through Moses and the Prophets to sapiential literature—the God who had shown his face only in Israel and who had been honored in the world of the Gentiles under obscure avatars—it is this God, the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, the true God, whom he brought to the peoples of the earth” (I, 63-64).

This thesis, as such, is explicitly repeated in the following volume of Jesus of Nazareth, this time with a significant emphasis on the universal dimension of Christ’s mission. “Even though Jesus consciously limits his work to Israel, he is still moved by the universalist tendency to open up Israel so that all can recognize in the God of this people the one God common to all the world” (II, 31). The answer to the decisive question “What does Christ bring?” naturally raises two other questions: to whom and how does Jesus bring God? This is the pole around which Ratzinger’s Christology is articulated, even though the expression, which he regrets in The Faith is so often opposed to “soteriology” or divided within it between “Christology from above” and “Christology from below” (155-156), only half suits him concerning his own work (cf. II, 10).

This Christology is thus elaborated in three stages. In the dialectic of the “new and definitive” on which Ratzinger, a reader of the Fathers, rightly insists in each mystery of Jesus that he contemplates, lies the key to the delicate articulation between Israel and the pagans. Both “light to enlighten the nations” and “the glory of [his] people Israel” (Lk 2:32), Christ is endowed with a mission whose very essence belongs to universality (III, 120). So much so that in the series of events in which God seems to disappear more and more—”land – Israel – Nazareth – Cross – Church” (176)—Jesus Christ presents himself as both the new Adam in whom “humanity begins anew” (III, 21) and the new Moses, the one who “brings to conclusion what began with Moses at the burning bush” (II, 113). The cross, for Ratzinger, is as much revelation as redemption. Now, what does this meeting of the vertical and the horizontal reveal, if not the identity of God and of man, in the person of the Son, a veiled response to the mysterious name given by God to Moses (Ex 3:14)? The cross, the only place where the divine “I am” can be known and understood (I, 377), consequently becomes the place where Christ reigns, His “throne,” “from which He draws the world to Himself” (II, 242). Christ’s being-open, with arms outstretched on the cross, goes hand-in-hand with Israel’s openness to the Gentiles: Ratzinger’s pro-existential Christology justifies Christian universalism.

“The Jew first, and the Gentile”

The great mission that Ratzinger sets himself at the beginning of Jesus of Nazareth, to represent the “Jesus of the Gospels” as a “historically sensible and coherent figure” (I, 17), amounts to rendering a reason for a “crucified Messiah” whom the Jews call “scandal” and the pagans “foolishness” (1Co 1, 23). Certainly, the passage from “do not go to the Gentiles” (Mt 10:5) to “make disciples of all nations” (Mt 28:19) in Christ’s teaching has found, from the earliest times of Christianity, a coherent interpretation in the Epistle to the Hebrews, in St. Paul and in the Church Fathers, based on “Israel according to the spirit,” “the time of the Gentiles,” etc. For all that, the fact that Henri de Lubac, in the previous century, saw fit to remind theologians, on the basis of scriptural and theological arguments, of the unity of the Ecclesia ex circumcision—the Church born of Israel—and of the Ecclesia ex gentibus—the Church of the Gentiles, (II, 255)—indicates how much the articulation between the Jewish and the “Greek element” (254) in the Christian mystery, although it is the foundation of all ecclesiology, still gives rise to a certain embarrassment. No doubt the “concern for universality”[3] of the Bible, brought up to date by the author of Catholicism, left its mark on the young Ratzinger. In an era still shaken by the discoveries of historical-critical exegesis, Henri de Lubac reaffirmed a fundamental exegetical principle proper to the Fathers: to learn to read historical realities spiritually and spiritual realities historically.

Strengthened by this spiritual hermeneutic and aware of the importance of the factum historicum as well as its limits, Ratzinger could respond to and overcome the apparent aporias of a historical-critical interpretation which, according to him, “has now given all that is essential to give” (II, 8). For someone familiar with St. Thomas Aquinas, this effort at theological synthesis is reminiscent of the method of the Summa Theologiae, whose Tertia pars, by his own admission, influenced Ratzinger’s work (II, 10). In Jesus of Nazareth, the questions are numerous and the theses, even those that the theologian refutes, are deployed to the end. For each mystery of the life of Christ, Ratzinger proceeds, as it were, by questions broken down into various articles within which, to the objections formulated—most often—by historical-critical exegesis, the theologian opposes a sed contra from an authority—Scripture or a Father—before proposing his own answer and solutions, arguing from theological, historical or scientific sources.

This issue of method tells us more about Ratzinger’s primary intention. Behind the demonstrative rigor, we can guess a will to make intelligible a mystery which, for many, appears scandalous or senseless. Intelligence of Scripture for the Jews, intelligence of faith for the pagans. Now the two, far from being opposed, communicate according to a precise hierarchy. The fact, in St. Augustine in particular, that the latter understands the former and exceeds it is justified, originally, in the person of Jesus Christ, who is both Jonah—”Καθὼς Ἰωνᾶς” (Lk 11:30)—and “much more than Jonah”—”πλεῖον Ἰωνᾶ” (Lk 11:32). Set in motion again by the Son of God, salvation history is also overtaken by Him. Here lies what Ratzinger considers “the central point of [his] reflection.” On the one hand, Christ is indeed a “new Adam” (I, 161), a “new Jacob” (I, 65), a new Samuel (III, 180), a new David (II, 17-18); “new Moses” above all, since the prophet spoke with God himself and received from him his mysterious name (I, 292-293). On the other hand, and at the same time, He is the “true Jacob” (I, 195), “true Solomon” (I, 106) and “true Moses” (I, 101): the Manna, the Divine Name and the Law, the three gifts given by God to Moses, have become one person: Jesus Christ. What God promises in the Old Covenant is fulfilled in the New Covenant: “by means of the new events… the Words acquire their full meaning; and, conversely, the events possess a permanent meaning, because they are born of the Word; they are Word fulfilled” (III, 39). From His ministry in Galilee to the ascent of Golgotha, Christ not only fulfills the Scriptures and keeps promises—by perfectly fulfilling the mission of the suffering Servant of God announced by the prophet Isaiah (Is 53), He goes beyond it and, by giving Himself up not only for the “lost sheep of Israel” (Mt 15:24) but also for the multitude, He gives it a “universalization that indicates a new breadth and depth” (II, 161).

This return to the first universality, the “new Adam” recapitulating the humanity wounded since the first Adam, was already announced in the existence of the particular people, chosen by God: Israel. According to the Augustinian tripartition, the regime of grace (sub gratia) which begins with Christ, although fulfilling the promises made by God under the regime of the Law (sub legem), gives humanity a new beginning and a universality unheard of since the time before the Law (ante legem). Now, with regard to the promises made to the Jewish people, Ratzinger recalls that in the Old Testament “Israel does not exist only for its own sake” but “to become the light of the nations” (I, 138): “its election being the way chosen by God to come to all” (I, 42). There is no lack of scriptural references to prove this, the most famous of which is found in the Song of the Servant in the book of Isaiah, where the figure of a man, familiar with the Lord and abused by his people, appears. “And he said: It is a small thing that thou shouldst be my servant to raise up the tribes of Jacob, and to convert the dregs of Israel. Behold, I have given thee to be the light of the Gentiles, that thou mayst be my salvation even to the farthest part of the earth.” (Is 49:6). By carefully analyzing these passages (I, 360, II, 235-237, III, 120), following many exegetes, Ratzinger affirms that by fulfilling this prophecy of Isaiah, Christ fulfills the promise of universality made to Israel. As the new Moses, He is the master of “a renewed Israel, which neither excludes nor abolishes the old, but goes beyond it by opening it to the universal” (I, 87). In Jesus Christ, the particular has become universal (I, 103). ” For he is our peace, who hath made both one, and breaking down the middle wall of partition, the enmities in his flesh:” (Eph 2:14), writes Saint Paul. So much so that the first affirmation of Ratzinger’s Christology, that Christ brought God, finds its meaning and its definitive scope in the theme of the universality of Jesus, “the very center of his mission” (I, 42). Jesus Christ “brought the God of Israel to all peoples, so that now all peoples pray to him and recognize his word in the Scriptures of Israel, the word of the living God. He has given the gift of universality, which is a great promise, an outstanding promise for Israel and for the world” (I, 139).

The “Burning Bush of the Cross”

Halfway through Ratzinger’s reflection, a question emerges. While it is easy to understand how the hermeneutical rule that Ratzinger borrows from the Church Fathers—the dialectic of “true and definitive” applied to the Old Testament figures that announce Christ—makes Scripture a harmonious whole, one is entitled to wonder what fate Christianity, in Ratzinger, has in store for the Gentile. “The Jew (Ἰουδαίῳ) first, and the Greek (Ἕλληνι)” (Rom 1:16): the formula, recurrent in St. Paul, recalls the order of priorities. However, the Greek is already concerned by the universal history of Israel, and in particular by God’s revelation to Moses in the Burning Bush (Ex 3). At Mount Horeb, the pagans who until then had been worshipping a God without knowing him, the “unknown God” (Ἀγνώστῳ θεῷ) whose inscription St. Paul discovers at the Areopagus in Athens (Acts 17:23), are summoned. They are also summoned to Sinai, where another theophany takes place that leads to the gift of the Laws, and, a fortiori, to the “new Sinai”, “definitive Sinai” (I, 87), which Ratzinger identifies with the mountain where the discourse of the Beatitudes takes place (Mt 4, 12-25) and, with even more reason, with Mount Golgotha (I, 167).

Historically, the sum of Ex 3:14 occurs in a context where the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob chooses a people and orchestrates their liberation from a pagan nation that held them in bondage. The particularity of the mode of revelation of the Divine Name does not, however, contradict the universal scope of its content. Anxious to interpret historical realities spiritually—and vice versa—Ratzinger proves this in various ways. First of all, through Scripture, he interprets the flight of the Holy Family into Egypt and the return to the Promised Land as a restart of the history of Israel, from its Mosaic origin (III, 159) to the Maccabean revolts. In His incarnation, the Word who was with God in the beginning comes into the world in Galilee, that is, “in a corner of the earth already considered half pagan” (I, 85) and receives Roman citizenship under the reign of Augustus, an emperor considered to be the son of God, if not God himself, and who has, without knowing it, contributed to the fulfillment of the promise by establishing political universality and peace in his Empire (III, 93-95).

From His native Galilee, the Messiah goes to Jerusalem, the city that kills the prophets and stones those who are sent to it (Lk 13:34), the place where salvation is to come at the end of an ascent to which Saint Luke, in his Gospel, has given a geographical as well as a spiritual connotation. He who found more faith in the pagans, who opened his door to Him, than in most of the children of Israel (Mt 8:10) who did not receive Him, made Jerusalem the center of a revelation that began with the adoration of the pagan magi in Bethlehem and is fully accomplished in the proclamation of Christ’s death and resurrection to all nations. Thus, at the other end of the New Testament, Ratzinger is right to interpret St. Paul’s vision of a Macedonian calling the apostle of the Gentiles to his aid (Acts 16:6-10) as a justification for what has been called, more often than not to criticize, the Hellenization of Christianity. “It is not by chance that the Christian message, in its development, first penetrated the Greek world and became involved in the problem of intelligibility and truth” (35).

Where some, fearing the dissolution of Christian specificity in Greek culture and philosophy, advocate a “retreat into the purely religious” (82), Ratzinger firmly supports the “inalienable right of the Greek element in Christianity” (35). The ontological interpretation that the Fathers of the Church, and the medieval theologians after them, gave to the “I am” by which God calls himself in Ex 3:14, is the basis, a few centuries after the Greek kick-off, for what Ratzinger dares to call the “identification” of the “philosophical concept of God” with the biblical God (66), with several not inconsiderable transformations (84-85). Pascal is at liberty, in a formula which has made history – often for the wrong reasons – to oppose the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob to that of the philosophers and scholars, without the choice of “primitive Christianity… for the God of the philosophers against the God of the philosophers”. ) for the God of the philosophers against the gods of the religions” (80), the “primacy of the logos” (91) inherent in the Christian faith would have been flouted and there would probably not be, to this day, philosophers and scholars to oppose to the Law and the prophets. In Ratzinger, we find what justifies the “metaphysics of the Exodus” that Stephen Gilson vigorously defended: the Christian God is the new and true Supreme Being of which Plato and Aristotle speak, once the “gap” that separates him from the biblical God has been reduced (66), once the “first immobile motor” has been transformed by contact with the God of faith (87-89). “In this sense, there is in faith the experience that the God of the philosophers is quite different from what they had imagined, without ceasing to be what they had found” (85).

If, at Mount Horeb, God reveals that He is the Being who subsists in Himself and gives all things their being, the revelation of the Divine Name does not entirely lift the veil on His essence. The sum qui sum, Ratzinger asks, is it not rather “a refusal than a declaration of identity?” (72) Opposing the gods that pass away with the God who is may resolve Moses’ immediate concern: the Divine Name allows the people to invoke God in their struggle and to guard against worshipping pagan idols. However, the immediate presence of God, “which constitutes the very heart of Moses’ mission as well as its intimate reason” (I, 292), is quickly “overshadowed.” The Lord’s answer to Moses’ prayer, “Let me behold your glory” (Ex 33:18), sets the limits of prophetic knowledge of God. The Old Covenant, in the end, “presents only the outline of the happiness to come, not the exact image of the realities” (Heb 10:1). The Old Testament prefigures and prepares (Rom 5:14) the one who will fully accomplish what began with Moses, but of which Moses is only a shadow (Col 2:17). In Israel, God accustoms people to His presence until the moment when, taking up the answer given to Moses on Sinai—”no one can see my face” (Ex 33:23)—he offers people, on His own initiative, to see and know Him in the person of Jesus Christ (Jn 1:18).

To say that “the last prophet, the new Moses, was given what the first Moses could not obtain” (1:25) is not only to emphasize the absolutely unique intimacy and covenant that is born with Christ, the Word of God, but also to consider His coming as the completion of the revelation made to Moses. If Ratzinger is concerned with noting, throughout the Gospels, and especially in Saint Matthew who insists particularly on the fulfillment of the Scriptures in Jesus, the way in which Christ is inscribed in the line of the great mediators of revelation, he does not fail to orient each correspondence towards the Christological summit which is the Cross. Ratzinger’s theology is clearly Christocentric, and his Christology is itself centered on the Cross. Theologia a Cruce, one could say, theology based on or leaning against the Cross, avoiding, with Father de Lubac, the equivocal expression, especially since Luther, of Theologia crucis. For Ratzinger, faithful to the patristic reading of Henri de Lubac, “it is the Cross that dissipates the cloud with which Truth was covered until then”[4]. This is true from the first announcements of the Passion to the “priestly prayer” of Christ reported by Saint John (Jn 17), which Ratzinger comments on in several places and in which he sees a “New Testament replica of the account of the Burning Bush” (76). “I have made known to them your name” (Jn 17:26), says the Son addressing the Father: “The name, which has remained incomplete since Sinai, so to speak, is pronounced to the end” (III, 51). Moreover, “the name is no longer just a word, but designates a person: Jesus himself” (77). Christ appears as the Burning Bush itself, from which the name of God is communicated to men.

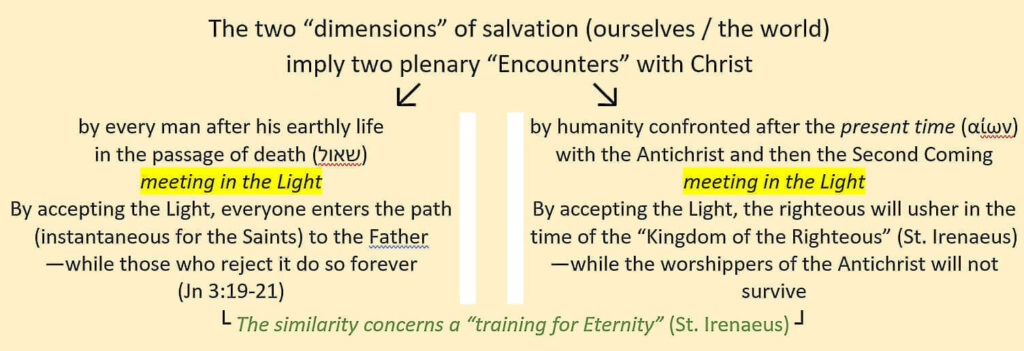

In this respect, there is indeed a “metaphysics of the cross” in Ratzinger, which extends and completes the “metaphysics of the Exodus.” In other words, the mystery of the Cross cannot be reduced to the mystery of redemption. In the history of salvation, redemption always follows revelation: God saves by showing Himself, by revealing what He is. This is evidenced by Ratzinger’s distinction between the two types of confession of faith in the Gospel: ontologically oriented confession, based on nouns on the one hand—you are the Christ, the Son of the living God, etc.—and verbally oriented confession based on the other—you are the Son of the living God.

On the other hand, there is a verbal confession oriented towards salvation history—the proclamation of the paschal mystery of the Cross and resurrection, etc.—and a verbal confession of faith in the Gospel. In the light of this fundamental difference, he states that “the statement in strict terms of the history of salvation remains devoid of its ontological depth if it is not clearly stated that he who suffered, the Son of the living God, is like God” (I, 326). In this way, the universality of the mission of Christ is respected, who, on the cross, is not the “king of the Jews,” a typically “non-Hebrew” expression used by Pilate (III, 145), but the “king of Israel,” according to a new kingship, the “kingship of truth” (II, 223), and at the head of an Israel that has become universal. “Universality… is put into the light of the Cross: from the Cross, the one God becomes recognizable by the nations; in the Son they will know the Father and, in this way, the one God who revealed himself in the burning bush” (II, 33). God manifests himself to the Greeks on the Cross: “between the pagan world and the blessed Trinity, there is only one passage, which is the Cross of Christ” (204), Ratzinger writes, quoting Daniélou.

Christology and Ontology

It is clear that for Ratzinger “the Cross is revelation” (206). But what does it reveal? Not “some hitherto unknown propositions” (207). It reveals who God is and how man is. The Cross combines the Ecce homo (Jn 19:5) of Pilate and the “Behold the Lord God” (Is 40:10) of the prophet. Golgotha, the “true summit,” is the condition sine qua non for knowing God, for understanding the “I Am” (I, 377). ” When you shall have lifted up the Son of man, then shall you know, that I am he, and that I do nothing of myself, but as the Father hath taught me, these things I speak” (Jn 8:28), writes the evangelist. Does this mean that the ontological statement of the Burning Bush would finally receive, with Christ, the object left dangling after the verbal form, ἐγώ εἰμι in St. John? Faithful to St. Augustine, Ratzinger rather sees Christ as the one in whom the Divine Name is pronounced perfectly. Better: the one in whom the Divine Name is realized, becomes actual. Just as in the Psalms, according to St. Augustine, “it is always Christ who speaks, alternately as Head or as Body” (II, 172), so on the Cross Christ becomes the subject of the divine “I am.” The mystery of the Passion of Christ is thus “an event in which someone is what He does, and does what He is” (197).

Here lies the singularity of Ratzerian Christology, marked by Johannine ontology and fertilized by the Aristotelianism of the medieval theologians. The being of Christ, Ratzinger reminds us in The Faith, is identical to his act. Borrowing from the notion of actualitas divina and the idea, of Thomistic origin but which he traces back to Saint Augustine, of “the Existence which is pure Act” (110), the theologian insists on the identity, in Jesus Christ, “of the work and the being, of the action and the person, the total absorption of the person in his work, the coincidence of the doing with the person himself” (151). The fusion, in the phrase “Jesus Christ,” of the name with the title testifies well to this identification of the function and the person (133). Therefore, one cannot separate the “Jesus of history” from the “Christ of faith,” as historical-critical exegesis has done on a massive scale, any more than it is possible to oppose a theology of the incarnation to a theology of the Cross. Ratzinger reconciles the two, since Christ’s being is actuality and, reciprocally, His action, is His being, reached to the depths of His being (155).

The same is true of “phenomenology and existential analyses,” to which Ratzinger grants a certain usefulness, while judging them insufficient: “They do not go deep enough, because they do not touch the domain of true being” (154). In the formula dear to Christian phenomenology—God is such as He reveals Himself—the verb “to be” takes precedence: identity is not valid as a simple equivalence—God would be such as He reveals Himself, a simple act of donation, the mode becoming substance—but as a properly metaphysical statement pronounced from the divine esse. The first affirmation of theology, that of Ex 3:14, would rather be: God is “as he is” (1 Jn 3:2). But, having renounced “discovering being in itself” in order to limit itself to the “positive,” to what appears, phenomenology, in the same way as physics or historicism, remains on the threshold of mystery. Ratzinger regrets that in our day “ontology is becoming more and more impossible” and that “philosophy is largely reduced to phenomenology, to the simple question of what appears” (127). But being and appearing, in Christ, are one and the same.

This “pure actuality” of Christ is first verified in the ad intra works of the Trinity. Ratzinger recalls that Father and Son are concepts of relationship. Thus “the first person does not engender the Son in the sense that the act of generation would be added to the constituted person; on the contrary, it is the act of generation, the act of giving itself, of spreading itself” (117). The “solitary reign of the category substance” is broken: “one discovers the “relation” as an original form of the being, of the same rank as the substance.” Consequently, the Johannine formula already quoted according to which the Son can do nothing of Himself, informing us about the Christic doing, also informs us about His properly relational being. “The Son, as Son and insofar as He is Son, does not exist at all on His own and is therefore totally one with the Father” (118). So that the being of Jesus appears to us, in the light of St. John, as a “totally open being,” “coming from” and “ordained to.” In Jesus of Nazareth, Ratzinger takes up this theme of “being-for” (Sein-für), borrowed in particular from Heinz Schürmann (II, 203). The pro-existence of Jesus means that “His being is in a being for” (II, 158). “In the passion and in death, the life of the Son of Man becomes fully ‘being for,’ He becomes the liberator and savior for “the multitude,” not only for the scattered children of Israel, but more generally for the scattered children of God… for humanity” (I, 360). The universality of the salvation brought by Christ thus finds its origin in this being-for and the implications ad extra of this intra-trinitarian identity of the Son. As a “true fundamental law of Christian existence” (172), the “principle of the for” thus justifies Israel’s reconciliation with the Gentiles (Eph 2:13-16): having given His life for all, Christ becomes the principle of eternal salvation “for all those who obey him” (Heb 5:9).

Jesus Christ brought God to mankind: here we return, after a detour through the history of salvation, to the Christological source of this obvious but fundamental affirmation that Ratzinger has seen fit to recall. As “God who saves,” Jesus is God for men, God among men, “Emmanuel.” The immanence of God, given to Israel “in the dimension of the word and of liturgical fulfillment,” has become ontological: “In Jesus, God has become man. God has entered into our very being” (II, 114). According to Ratzinger, more than vicarious satisfaction, humanity receives its salvation from the identity, maintained in Jesus Christ, of the two natures; and with it, the identity between its being and its doing. On the Cross, the identity of God is perfectly realized in Christ, and thus visible to all: He is truly the one who gives Himself. Redemption is played out first in this perfect fulfillment of the “I am.” The identity of God, which is the subject of so many questions in the Old Testament as in Greek philosophy, is revealed on the Cross and is revealed precisely as an identity. God, in Christ, is truly what He is. On Calvary, “love and truth meet” (Ps 84:11), a theme that Benedict XVI will regularly expound during his pontificate.

Therefore, the divine being is open to the world and offers a previously unknown way to ensure the return of creation to God. Jesus Christ is this way, this “path” (Jn 14:6). The union achieved in Jesus of Nazareth “must extend to the whole of Adam and transform him into the Body of Christ” (182). The path taken by the Lord, in which Jews and Gentiles walk together, presents itself to humanity as an ascent to the Cross combined with a progressive renunciation of self.

Romano Guardini, whose influence on Ratzinger’s theology is well known, writes in this sense in The Lord that Christ’s life consists, after having lowered divinity towards humanity, in “[lifting] his humanity above itself into the divine ocean”[6]. In Guardini’s work, we can already see the literary and theological coincidence between the ascent to Jerusalem, where the King of Glory gradually understands that He will have to pass through the figure of the Suffering Servant, and the constitution of an economy of salvation, faithful to the promise that God’s salvation will reach all nations. The wider opening of salvation and hope has a condition: the deeper humiliation of Christ. What Christ gains in annihilation, humanity gains in elevation; and vice versa, since “the ascent to God happens when we accompany Him in this abasement” (I, 117). “Only with Christ, the man who is “one with the Father,” the man through whom man’s being has entered into the eternity of God, does man’s future appear definitively open” (254). This is the true lordship and authentic kingship that God exercises through Christ: The Master of the universe, fulfilling the ancient proskynesis, lowers himself to the extreme limit of self-emptying, becomes a servant. The “sons in the Son” will be recognized by the fact that they remain eternally in the house where their master (Jn 8:35), because they have asked for it (Jn 1:38), has brought them: the dwelling place of being which is that of love (Jn 15:9). Great mystery of a faith where one reigns in service (I, 360), since the dominus or κύριος, in order to be never again separated from His creation, united Himself to it, engulfed Himself in the “heart of the world” to such a depth that any fall in the future would be a fall in Him.

Augustin Talbourdel: cogito a Deo ergo sum. This article appears courtesy of PHILITT.