“God, source of inspiration of Don Quixote; the Bible, model of organizational structure of Don Quixote; and Catalina de Salazar y Palacios, love of the famous Manco and his source of human inspiration, are part of Don Quixote de la Mancha, by Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra.”

The Bible, translated into 450 languages in full and more than 2000 in part, written by men and inspired by the majestic and mighty Lord God, is part of Don Quixote de la Mancha (1605 & 1615), which has been translated 1140 times into some 190 languages and dialects. It was written by the brilliant Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616), hero of the Battle of Lepanto (1571), exemplary slave in Algiers (1575-1580), and perpetual reader of the true riches of the Old and New Testaments, for whom Jesus Christ was “God and true man” (Don Quixote, II-XXVII), and for whom the wish about the Bible came true: “It is clear to me that there should be no nation or language where it is not translated” (Quixote, II-II).

Don Quixote contains 181,104 words, of which 22,939 are unique; and the infinite wisdom of the Word of God left traces in the soul of Miguel, who loved God and the Bible, guide of his life, for he evoked the Bible three times in the “Prologue” of the first part of Don Quixote, “the Divine Scripture,” and he made authentic display of his vast biblical knowledge throughout his works; he alluded to thirty biblical characters, dealt with 300 references to the Bible, and included countless allusions and reminiscences of the Holy Scripture.

The Bible, the Book of books, whose principal inspiration is God, and Don Quixote, a human jewel of incalculable magnitude; both books of varied readings—on the absolute truth and undeniable existence of God, the superlative role of God in human thought and life, the direct and indirect communication between God and man, and the transcendence of divine life in the human heart—both books love Humanity and speak to our hearts.

However, it is not my goal to compare the Bible and Don Quixote because man can never equal God, for the Bible is incomparable and unsurpassable, and God clearly proclaims it this way: “I am the first and the last, besides me, there is no God, who is like me? Let him arise and speak. Let him proclaim it and argue against me” (Isaiah, 44: 7).

Even Miguel criticizes the comparison between the human and the divine as follows: “nor has he any reason to preach to anyone, mixing the human with the divine, which is a kind of mixture of which no Christian understanding is to be clothed. He only has to take advantage of imitation in what he writes, and the more perfect it is, the better will be what he writes: (Q, I, “Prologue”).

I still want to make special emphasis, inter alia, that the precious treasure of the Bible and the precious treasure of Don Quixote, both works of inestimable value for Humanity, are concerned with ethics, morality and religion in the behavior of the human being, that is why the phrase: where is your treasure there is your heart, comes here like a ring to the finger.

Cervantes’ thoughts and words, in all his works, are influenced by God through the Holy Spirit, despite the fact that some “academics of excellence” completely reject his knowledge of the Bible, but continue to ask without hitting the mark: how to approach Don Quixote? What to do and where to start? What are the tips for reading Don Quixote? What is the challenge of reading it? Why is it so difficult to understand it? And how to read Don Quixote?

The answer is very simple, but it is essential to leave aside all myths, fantasies, and hypocrisies; that is, before approaching Don Quixote, the works of Cervantes, and those of the geniuses of Spanish Golden Age literature, one must first and unavoidably read the Bible, and then acquire a solid knowledge of the origin of Spanish literature up to the dissemination of the masterpiece of world literature, Don Quixote (1605 & 1615).

This is the only infallible way or the only golden key to easily read and understand Cervantes, Don Quixote, and the best literature in the world, which is Spanish literature—exemplary, majestic and superior to all, in essence, is that of the Golden Age—headed by the brilliant novel of the distinguished leader of universal literature, Miguel, lover of books, who always read, taught and loved the Holy Scripture, par excellence, and with which he identified himself during his life trajectory at all times.

Cervantes is fully aware of the value of the Bible, speaks of the truth in the Sacred Scripture, advises us to read it: “If… he wants to read books of exploits and chivalry, read in Sacred Scripture the ‘Book of Judges,’ and there he will find great truths and deeds as true as brave” (Q, I-XLIX), and confesses that “Holy Scripture… cannot lack an atom in truth” (Q, II-I), and eternalizes his biblical knowledge and the greatness of God’s love in his works.

Certainly, Miguel loved the Bible, book of the history of the world, of poetry, and of wisdom, in which, as an example, the Book of Psalms, the Book of Proverbs and the Song of Songs are sublime, despite the fact that some “scholars of excellence” left Miguel’s knowledge of the Holy Scripture in the dark without any compelling reason manifested in the masterpieces of the genius of universal literature.

In addition to this, I should add that the meritorious historian José Luis Abellán García-González affirms that “Don Quixote is the Spanish Bible” (Visiones del Quijote, 130). The meritorious professor Alfonso Ropero Berzosa writes that it is the “Bible of universal literature, which is illuminated by the Christian Bible, from which Cervantes extracts the idea of justice and freedom so human and so divine” (El Quijote y la Biblia, 10). The extraordinary historian Sabino de Diego Romero, President of the Cervantine Society of Esquivias, says of Catalina, in his magnificent work: Catalina, fuente de inspiración de Cervantes (Punto Rojo, 2015), says through the mouth of Don Quixote, “because blood is inherited, and virtue is acquired, and virtue alone is worth what blood is not worth” (Catalina…, 242). And the excellent writer Eduardo Aguirre Romero declares with greater precision that “in these uncertain times, Miguel de Cervantes still has much light to offer us” (“Si Cervantes levantara la cabeza,” Diario de León, 27-III-2022).

Therefore, the questions arise; should we read the Bible and Don Quixote compulsorily in universities and schools? What are the reasons for reading such works? The answer is, yes. The Bible, God’s wisdom, and Don Quixote, human wisdom, are my daily readings for beauty, wonder, power, wisdom, truth, and virtues, among many.

Indeed, the spirit of both works pierces the soul like the sharp two-edged sword or the sword of Achilles of Troy, and both works are for the people; they speak of love and lovelessness, of good and evil, of the beautiful and the noble; they are concerned with humanity; they penetrate our human hearts; and they teach us to love one another and become better people.

The Bible, the wonderful book, can be read every day; it only needs 11:59 minutes; and if you start it on January 1st, you will finish it on December 31st of the same year. Or, I recommend you to listen to the Bible published by the University of Navarra in audiobook format. Don Quixote, the Bible of Humanity, can be read daily; it only takes 4:43 minutes; and if you start it on January 1st, you will also finish it on December 31st of the same year; or you can listen to it on Cadena SER.

You will not regret reading day after day the glorious Bible and the ingenious nobleman Don Quixote. You will always discover something new. You will feed on the wisdom of God and the wisdom of the famous Manco de Lepanto, and you will be provided with infinite benefits. Read every day the Bible and Don Quixote de la Mancha!

Laus in Excelsis Deo.

Krzysztof Sliwa is a professor, writer for Galatea, a journal of the Sociedad Cervantina de Esquivias, Spain, and a specialist in the life and works of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra and the Spanish Golden Age Literature, all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles and reviews in English, German, Spanish and Polish, and is the Corresponding Member of the Royal Academy of Cordoba and Toledo.

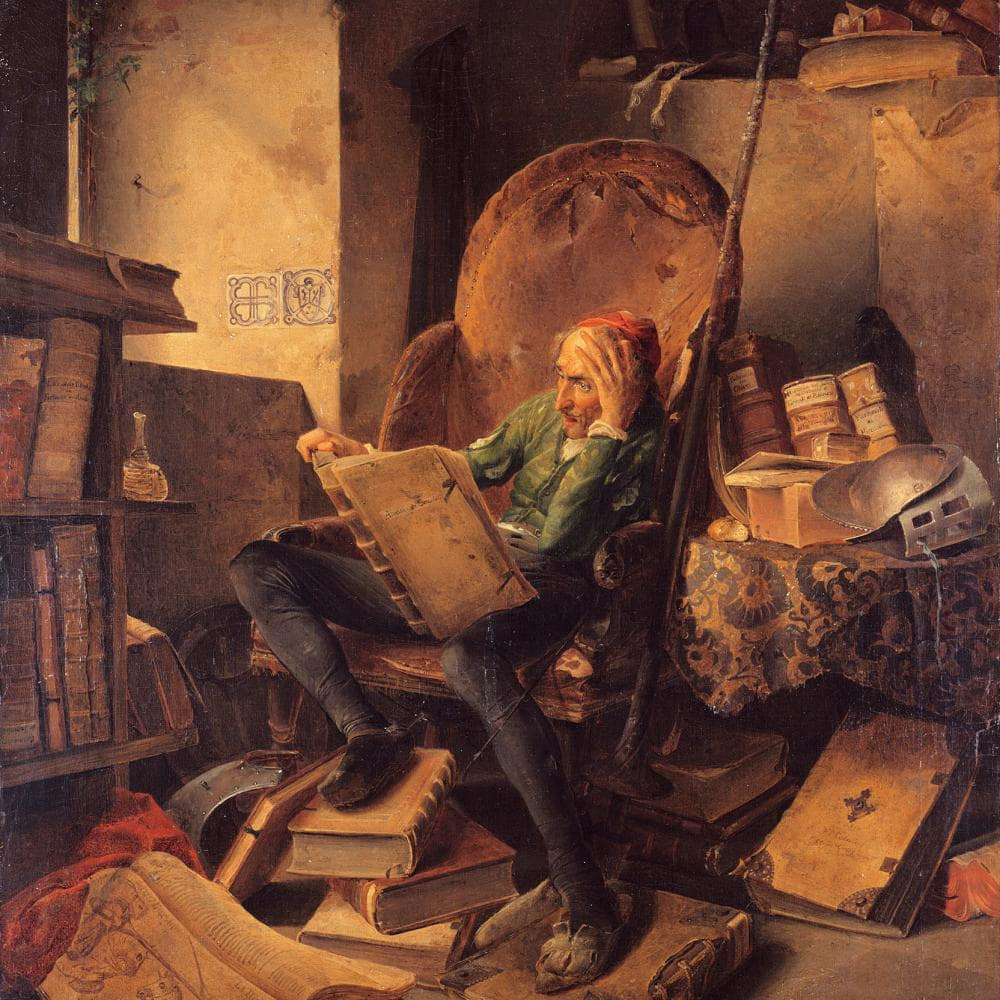

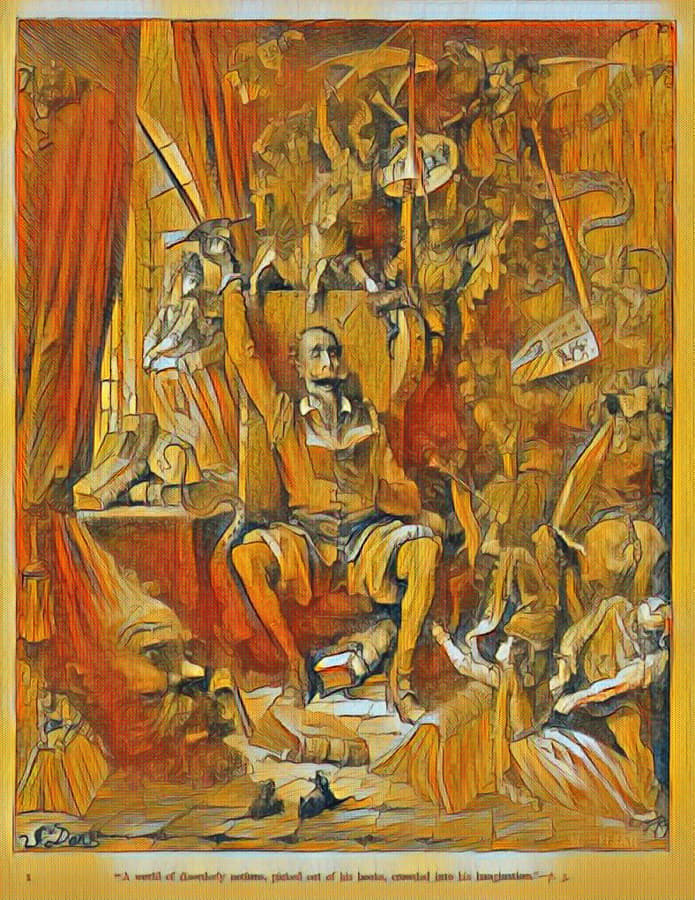

Featured: Don Quijote in der Studierstube lesend (Don Quixote in the Study Room, Reading), by Adolf Schrödter; painted in 1834.