“Military service, under the banner, of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, brilliant soldier of the Elite Special Forces of the Spanish Old Tercios, at Lepanto, soul of every soldier and heart of Spain, is a divine virtue.”

For the first time since the death of the “King of Spanish Literature,” 407 years later, I have the great honor of dedicating a brief study to the invincible standards of the glorious Man of La Mancha, who loved them with all his heart and soul and defended them with the highest dignity, nobility and courage because “the soldier seems more likely to be dead in battle than alive and safe in flight” (Don Quixote, II-XXIIII).

Here the words of Major General (R) Rafael Dávila Álvarez come readily to mind: “There is nothing like the Spanish soldier, and my only aspiration has always been to be at his level.”

Under threat of imminent war against the Ottoman Empire of Selim II (1524-1574), Cervantes entered his first military service in Italy, and thanks to the recommendation of Giulio Acquaviva d’Aragona and Giovanni Girolamo I Acquaviva d’Aragona (1521-1592), the tenth Duke of Atri, and that of his son Adriano Acquaviva d’Aragona (1544-1607), very good friends of General Marcantonio Colonna (1535-1584), of whom Cervantes had heard “have often heard Cardinal de Acquaviva tell of your Lordship [Ascanio Colonna, Abbot of Santa Sofia] when I was his chamberlain at Rome” (Galatea, 1585).

Indeed, Cervantes’ first military mission began under the command of Marcantonio, who led numerous naval operations before the battle of Lepanto, and whom Cervantes served for more than two years, according to the dedication of La Galatea addressed to Cardinal Ascanio Colonna (1560-1608), where he affirmed that “I may at least deserve it for having followed for several years the conquering standards of that Sun of warfare whom but yesterday Heaven took from before our eyes, but not from the remembrance of those who strive to keep the remembrance of things worthy of it, I mean your Lordship’s most excellent father.”

To Cervantes it was an opportune occasion to restore his reputation and to enter the army because “the Turk was coming down with a powerful armada and his design was not known, nor where he was going to unload such a great cloud” (Don Quixote, II-I). Therefore, on June 5, 1570, Pope Pius V (1504-1572) appointed the Roman Marco Antonio Colonna, the general in chief of the pontifical squadron, and on July 15 of the same year, the “Prince of Christendom” ordered “his commanders in Italy to place themselves under the orders of the General of the Armada of Pius V” (A.Z. c. 51 no. 2).

According to the historian Ricardo de Hinojosa y Naveros (Los despachos de la diplomacia Pontificia en España,185-86) Marcantonio was general of the pontifical galley squadron before April 1570, which was part of the twelve galleys assembled along with the sixteen galleys of the Genoese admiral Giovanni Andrea Doria on September 1, 1570 in La Suda in order to organize the relief-expedition of Cyprus and to raise the siege of Nicosia.

Cervantes joined the Pontifical Armed Forces in early 1570 and took part in the unsuccessful campaign for the relief of Nicosia, whose was launched on August 30, 1570 and then abandoned after the loss of Nicosia.

Cervantes details that they arrived “at the strong island of Corfu, where they took water” (The Liberal Lover) and then crossed the place where The Liberal Lover began: “O pitiful ruins of wretched Nicosia, scarcely wiped with the blood of your valiant and unfortunate defenders!” and tells that “looking from an outcrop at the demolished walls of the already lost Nicosia; and so he spoke with them, and compared their miseries to his own, as if they were capable of understanding him.”

Cervantes undoubtedly served in a company of Marcantonio until the arrival of his brother Rodrigo in Genoa, on July 26, 1571, who was one of the 2,259 soldiers of the company of Captain Diego de Urbina, deployed in the Tercio of the field commander Miguel de Gurrea y Moncada (ca. 1549-1612) and in that of Lope de Figueroa, who crushed the Alpujarra rebellion under the command of John of Austria and the Third Duke of Sessa.

Cervantes alludes to the arrival of John in Genoa, on August 6, 1571, who on August 9, 1571 went on to Naples, as follows: “My good fortune would have it that Senor Don John of Austria had just arrived in Genoa and was passing on to Naples to join the Venetian armada” (Don Quixote, I-XXXIX).

Military historian Juan Luis Sánchez Martín thinks that Cervantes enlisted in Diego de Urbina’s company “between August 9 and August 19, 1571 in Naples” (Los capitanes del soldado Miguel de Cervantes, 176) and the letter of August 25, 1571 from Don Juan to García Álvarez de Toledo Osorio (1514-1577), captain general of the galleys of Naples, evidences the appearance of Spanish troops in the Venetian squadron thus: “I found here Marco Antonio de Colonna with the twelve galleys of his Holiness, which are in his charge, well in order; likewise I found Sebastián Vernier, general of the navy of the Venetians, with forty-eight galleys, six galleys and two ships” (M. Fernández Nieto, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, Don Quijote de la Mancha, 214-15).

On September 1, 1571 the sixty galleys from Venice arrived in Messina, and on September 8 Don Juan reviewed the fleet “in which he had boarded on his ships, the Venetians, 4000 soldiers, for the service of the king of Spain;” and on September 9 in Leguméniças he communicated that “with the occasion of a dispatch that I sent to Naples it has seemed to me to advise you that these Venetian gentlemen at the end have finished resolving to take in their galleys four thousand infantrymen of those of S. M… that is to say, 2500 Spaniards and 2500 Spaniards, that is to say, 2500 Spaniards and 1500 Italians” (J. A. Crespo-Francés, Miguel de Cervantes, 8).

On Sunday, October 7, 1571, Cervantes was part of the Third Squadron of the fifty-four ships of the Venetian commander Agustín Barbarigo (1500-1571), located on the left wing of La Real, led by Don Juan, about which on March 20, 1578, Ensign Mateo de Santisteban stated thus: “To know the said Miguel de Cervantes, which was the day that the said Cervantes served in the said battle, and was a soldier of the company of Captain Diego de Urbina in the galley Marquesa, of Juan Andrea” (K. Sliwa, Documentos De Miguel De Cervantes Saavedra, 49-50).

This statement proves that Cervantes fought in the only Genoese galley Marquesa, commanded by the Italian captain Francisco Molin, belonging to Admiral Giovanni Andrea Doria, No. 34 of the Third Squadron of the Venetian commander Augustin Barbarigo, second in the high command of the Venetian Fleet after the Venetian Admiral Sebastiano Venier (1496-1578).

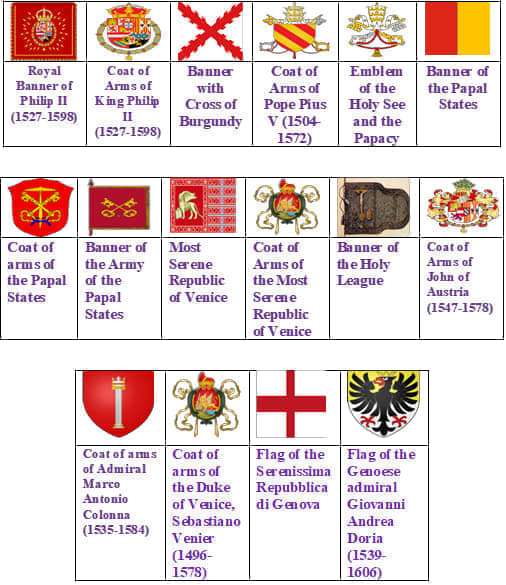

At Lepanto, Cervantes was among, inter alia, the following standards:

Before ending this brief summary on the legacy of Cervantes, hero of Algiers, who infinite times, with tears of love, kissed the flag of his homeland, heart of Spain, I thank the excellent military historian and Infantry Brigadier, Miguel Angel Dominguez Rubio, decorated with the Cross of Military Merit with White Distinctive, the Cross of the Royal Military Order of San Hermenegildo and the NATO Medal, Head of the Communication Office, Infantry Regiment, “Tercio Viejo de Sicilia,” N. No. 67, and author of the exemplary book: 1719-2019 Tercio Viejo de Sicilia nº 67: 300 años de la llegada a San Sebastián (Halland Books, 2019), in collaboration with Josué del Cristo Pineda Gómez. His love, sacrifice and bravery to Spain, homeland of heroes, and his gift of the shoulder flash, the medal with the words: “Valor, Firmeza y Constancia” [Courage, Firmness and Constancy], and the pocket flag of the Infantry Regiment, “Tercio Viejo de Sicilia,” No. 67, whose words ennoble all of us, who love “our sweet Spain, beloved homeland” (Treatise on Algiers):

With this Flag on your pocket, you will always carry with you a piece of our Homeland. It will help you to keep your commitment of Service to Spain. It will remind you of all those who fight by your side and are proud of your sacrifice and it will give you the strength will give you the strength for your dedication in the defense of our Nation, its values and its freedom.

I conclude by making a special emphasis that our exemplary and excellent Infantry Regiment, “Tercio Viejo de Sicilia”, No. 67, has as a collective pride to recite every morning the Camino del Sicilia, the stanzas that form the essence of our identity, and the voice of the colonel who exhorts us loudly: “This is the old Third!” And everyone responds with the verses of the Camino del Sicilia: “This is the old third,

which in death has proven more than a thousand times its nobility!” And this compendium of virtues and commitments is sealed with our “Battle Cry,” that is answered by the three words of response: “In combat, courage!”

“In our ideals, steadfastness! In preparation, constancy!” (M. Á. Domínguez Rubio, 1719-2019, Tercio Viejo de Sicilia, 50).

Laus in excelsis Deo.

Krzysztof Sliwa is a professor, writer for Galatea, a journal of the Sociedad Cervantina de Esquivias, Spain, and a specialist in the life and works of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra and the Spanish Golden Age Literature, all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles and reviews in English, German, Spanish and Polish, and is the Corresponding Member of the Royal Academy of Cordoba and Toledo.

Featured: The Battle of Lepanto, fresco by Giorgio Vasari; painted ca. 1572-1573.