The accomplished humorist, Eduardo Aguirre Romero, author of the magnificent books, inter alia, Cine para caminar (Walking Cinema), Blues de Cervantes (Cervantes Blues); Cervantes, enigma del humor (Cervantes, The Enigma of Humor) prologued by the writer Víctor Fuentes, has just published his masterpiece, Entrevista a Cervantes (Interview with Cervantes), which is dedicated “with gratitude and affection to the memory of the architect Jesús Martínez del Cerro (1948—2022), builder of the two prototypes of the machine to detect false readers of Don Quixote.”

“Don Quixote opened the way to a more humanitarian comicality”

In this context, it should be emphasized that Eduardo Aguirre Romero, journalist at the Diario de León, offered a reading workshop in the León City Hall, entitled, “Don Quixote for the elderly,” and he promotes the language of sweet Spain, by way of his first-rate works, in which, to better understand the life and works of the “King of Spanish Literature, he gives special emphasis to the humor of Cervantes, a subject of capital importance but very little studied by scholars.

But, before continuing, it is important to add a word about Cervantes, enigma del humor (2017), in which Aguirre Romero (who is originally from Madrid and now based in León since 1985) clearly deduces that in Don Quixote, humor rhymes with both love and pain and states that Cervantes’ humor is a multifaceted one, as “it does not evade your reality; it helps you to interpret it” (Cervantes, enigma del humor).

The insightful wit of Aguirre Romero accurately detects that “in these uncertain times, Miguel de Cervantes still has a lot of light to offer us.” As well, he meditates on the origin of humor and comes to the conclusion that “the best thing would be to ask Cervantes himself” (Cervantes, enigma del humor).

Consequently, in his Entrevista a Cervantes, “a work in progress,” the Cervantes-enthusiast from León converses with the genius of Spanish literature, not only because the immortal Miguel is still alive but also because the interviewer wishes to give the biography of the glorious man of La Mancha, in order to learn about the trajectory of his enigmatic life. Therefore, Aguirre Romero brings Cervantes to life, in flesh and blood, gives him a voice with all the freedom of expression and opinion; and without disguising the truth, even if it is unpleasant, he gives a biographical sketch of the famous Alcalá native.

Regarding his economic situation, Miguel maintains that “I had good times… but in my last years, if it wasn’t for the Count of Lemos and the Archbishop of Toledo, I would end up in a corner with a monkey and a goat. Isn’t that poverty? I had it tattooed on me since childhood” (Cervantes, enigma del humor, 48).

“All that can be forgiven, and more. When the time comes”

When asked about the words of the Spanish writer, Miguel de Unamuno (1864-1936), who belonged to the “Generation of ’98″—”’Don Quixote is immensely superior to Cervantes,’ what do you think?” The peerless novelist answers that “He is worth more than me… and more than almost all of us, because he does not condense. And Sancho also condenses us. But read, read, for sure there is more material to cut” (Cervantes, enigma del humor, 50).

Referring to Avellaneda, Aguirre Romero asks, “Can that also be forgiven, that in addition to murdering the book, he defamed you in the prologue? He even bragged about wanting to take away your profit, besides making certain allusions to… your horns.” Miguel replies that “all that can be forgiven, and more. When the time comes” (Cervantes, enigma del humor, 57).

“Thank you, O Lord, for you have revealed these things to the simple and you have hidden them from the wise.”

Similarly, the journalist sheds light on the doubts surrounding the character of Cervantes, who does not mince words and confesses that “I was wounded in my self-love, many times. Battered, too. I was even tempted to give up… but I was never rancorous. Nor vindictive, except for a few blows in this prologue or in that sonnet, because we are not of the same mind” (Entrevista, 58); and further on he declares that “one can be very intelligent and not understand anything. In fact, it is often those who understand the least. There is a very beautiful phrase of Jesus: ‘Thank you, Lord, for you have revealed these things to the simple and hidden them from the wise'” (Entrevista, 64-65).

The humorist Aguirre Romero notes that “Cervantes was the first to combine with genius the dramatic and the comic; that laughter was more than laughter… and no one before had so united comedy with depth and compassionate tenderness, though Cervantes himself often ignores such potential… and to perceive it, he had to fall in love with his characters, to feel responsible for them… There is not a comic Quixote and a serious Quixote. It is a single book. That is the marvelous multifaceted condition of Cervantes’ humor. A single humor, with numerous registers” (Entrevista, 34-35).

However, the key question that the author poses to Cervantes is:

Aguirre: “Where does Cervantes’ humor come from? You were poor in fits and spurts, you were crippled in a battle, you were imprisoned for five years, you were jailed several times for alleged embezzlement, you got along badly with your daughter… in old age you had to ask for help to survive… With that biographical background, where did you get the vital forces to write the universal masterpiece of humor?”

Cervantes: “Precisely from there… from pain.”

Aguirre: “Does his humor come from pain?”

Cervantes: “From pain and love. When he had the worst time… he laughed. And not only that, he was capable of making others laugh… Only fools need to smile when things go well for them. [If they steal your humor, they will have defeated you (Entrevista, 65).

“My humor comes from pain and love”

In all honesty, Entrevista a Cervantes is a well of wisdom, where humor and truth emerge, which characterize the writing of Aguirre Romero, who always follows the proverb of Cebantes, that brilliant soldier of the Elite Special Forces of the Spanish Tercios Viejos: “Be brief in your reasoning, because no one is pleased if it is long;” and he hides “an ace up his sleeve: there is also pain and love hidden behind what—a priori—only seemed funny” (Entrevista, 34).

Before concluding, it is my great honor to congratulate not only Eduardo for his excellent work that carries much of him within it, but also for his proclamation of vital joy—and that of the believer—in a period of great economic concerns due to the crisis, from which he has not been spared, but also to Professor María Fernández Ferreiro, the editor of Entrevista a Cervantes, for her excellent series of books that she has gathered, and the extraordinary Grupo de Estudios Cervantinos (GREC) at the University of Vigo.

Without the slightest shadow of a doubt, this masterpiece of our admirable Eduardo Aguirre Romero, “dedicated to society hit by a long economic crisis and a crisis of values” (Entrevista, 37), which fills the heart with greater joy, has managed to combine the funny with the serious. The characters and themes are identified with those of Cervantes’ works, while the entire work stems from a healthy and wise humor, which captures the soul of the reader, and makes us better people.

All this proves that Entrevista a Cervantes is a flagship and this book belongs to the whole world. Congratulations!

Laus in excelsis Deo.

Krzysztof Sliwa is a professor, writer for Galatea, a journal of the Sociedad Cervantina de Esquivias, Spain, and a specialist in the life and works of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra and the Spanish Golden Age Literature, all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles and reviews in English, German, Spanish and Polish, and is the Corresponding Member of the Royal Academy of Cordoba and Toledo.

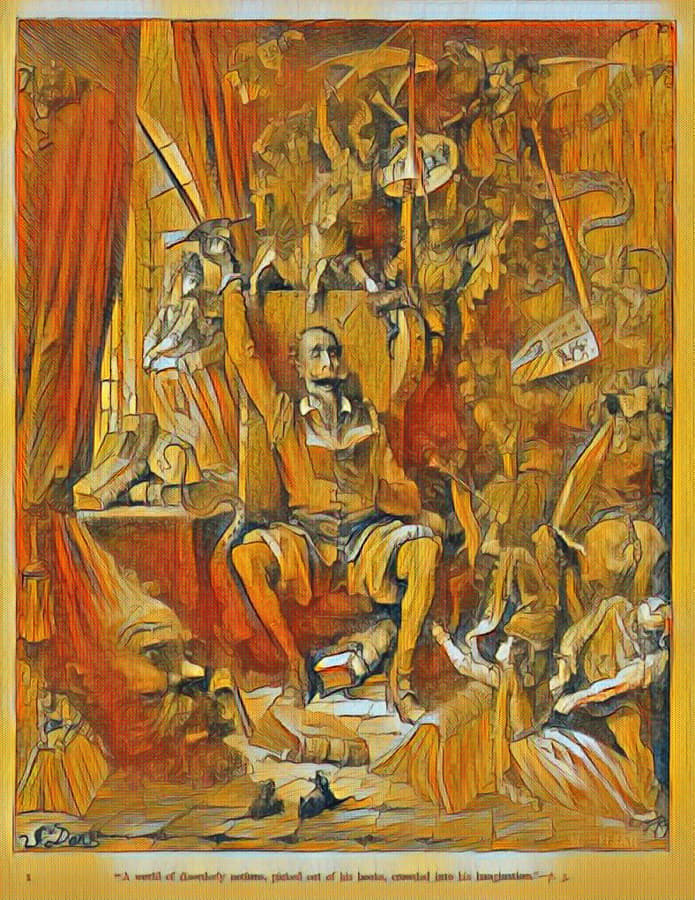

Featured: Miguel de Cervantes, Gustave Doré; published in 1863.