“Oh, sweet Spain, beloved homeland.” Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra.

The distinguished historian, Don Sabino de Diego Romero, President of the Cervantes Society of Esquivias, former mayor of Esquivias, and author of excellent books and articles, including Genealogía de Fray Francisco Ximénez de Santa Catalina, fraile de la Santísima Trinidad de Calzados, natural del Lugar de Esquivias, que fundó un hospital en Túnez (Genealogy of Fray Francisco Ximénez de Santa Catalina, friar of the Holy Trinity of Calzados, native of the Place of Esquivias, who founded a hospital in Tunis), Cervantes y Esquivias, lo que todos debemos saber (Cervantes and Esquivias. What We All Should Know), and Catalina. Fuente de inspiración de Cervantes (Catalina. Cervantes’ Source of Inspiration), discovered a new document about a real person in Don Quixote.

In 2015, Diego Romero published Análisis biográfico sobre Catalina de Salazar y Palacios (Biographical analysis on Catalina de Salazar y Palacios), which provided new, unpublished documents on the barber Mease Nicolás, a character in Don Quixote, that most outstanding work of universal literature by the “king of Spanish literature.”

According to the excellent documentary work of Diego Romero, from the of the time of the publication of Don Quixote, in 1605, Cervantine researchers have been making all kinds of speculations about whom Cervantes took as literary models, starting with Don Quixote himself and continuing with characters, such as Sancho Panza, the priest Pero Perez, as well as a character whom Cervantes gave the responsibility of bringing Quixote’s “madness” to a happy ending, namely, the barber Maese Nicolás.

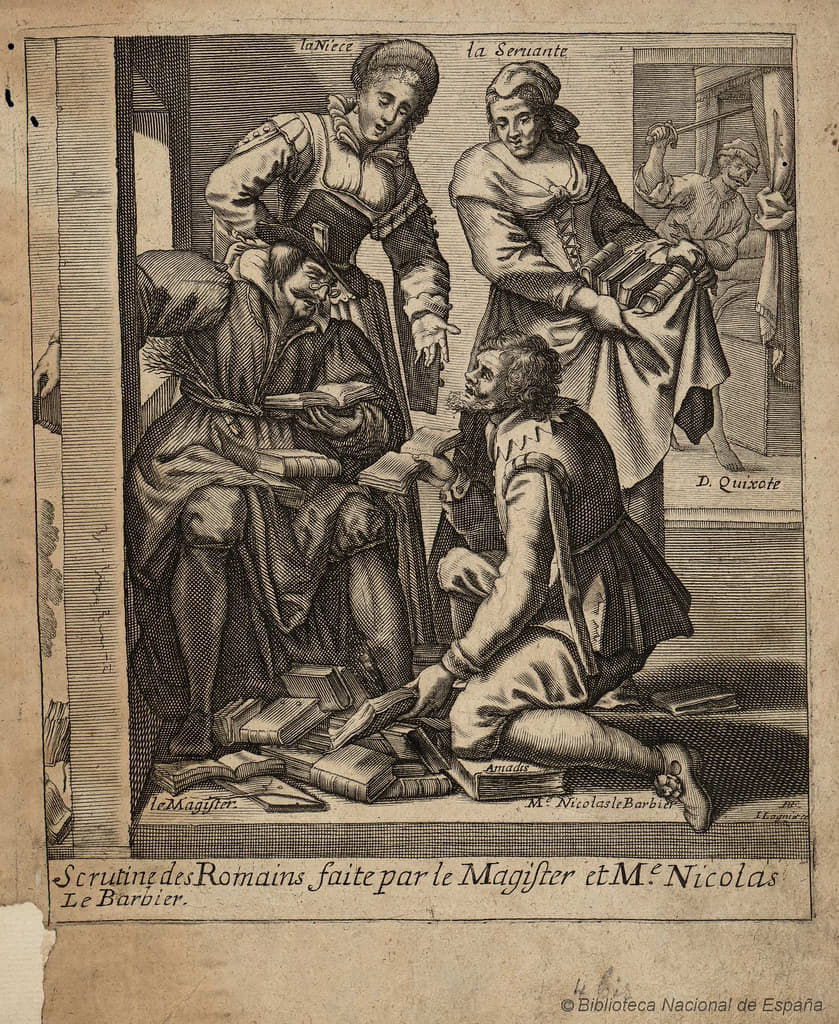

In this sense, it should not be forgotten that Maese Nicolás is introduced by Cervantes, for the first time, in Chapter V of the Part One of Don Quixote, together with the priest Pero Pérez, both residents of Esquivias, who eagerly conspire to bring Don Quixote back to his senses and are found in Quixote’s library, burning the pernicious books that altered his mind, in the opinion of both characters, found in Quixote’s library.

Therefore, in this context, I would like to emphasize that according to Don Sabino de Diego Romero, the barber’s shop, together with the tavern, were the ideal places for conversation among neighbors, and playing the guitar, and being also the centers of attention and influence. The barber, tonsor (of medieval origin), in addition to shaving beards, exercised the function of tooth-puller, performed bloodletting, healed wounds, bruises and broken bones well into the nineteenth century, when doctors became an independent guild and looked after the ailments once taken care of by the barbers. The barber of Esquivias was the one who took care of the tonsure—popularly known as coronilla (“crown”)—of Father Pero Pérez, priest of Esquivias, who exercised his pastoral work in the hermitage of San Bartolomé, in the outskirts of the town. The number of services rendered by the barber meant that:

“The influx of people to the barber’s shop was such that this place was the most frequented for social interaction and public discourse, where public forums were formed, for open debates with the participation of the locals on current issues.

“In small towns, in the absence of a regular doctor, it was the barber-surgeons who looked after medical needs, and accompanied the physician in his sporadic visits to the sick of the place.

“This meant that the affluence to the barbershop was massive and the barber needed the assistance of a good number of people, women in this case, who helped, cleaned, and produced soaps for personal use that were sold in the establishment, among other things.

“Likewise, as the shaving process was slow, given the deficient tools used, this meant an inevitable delay, resulting in the crowding of people in the barbershops being greater than in the taverns.”

Without a hint of doubt, Don Sabino de Diego Romero has found in Esquivias the barber-surgeon of the last third of the 16th century, whose name was Nicolás de Olmedo, a person of primordial influence among the commoners of the town. His opinion was respected by all, even by the noblemen of the town, who were also his clients, since the Master Barber, Nicolás de Olmedo, exercised a decisive influence between the two cultural strata of the town of Esquivias, noblemen and commoners, both for being the center of attention in his barbershop, as well as the natural gratitude of the families of Esquivias, for hiring a good number of young girls for the many services at his shop.

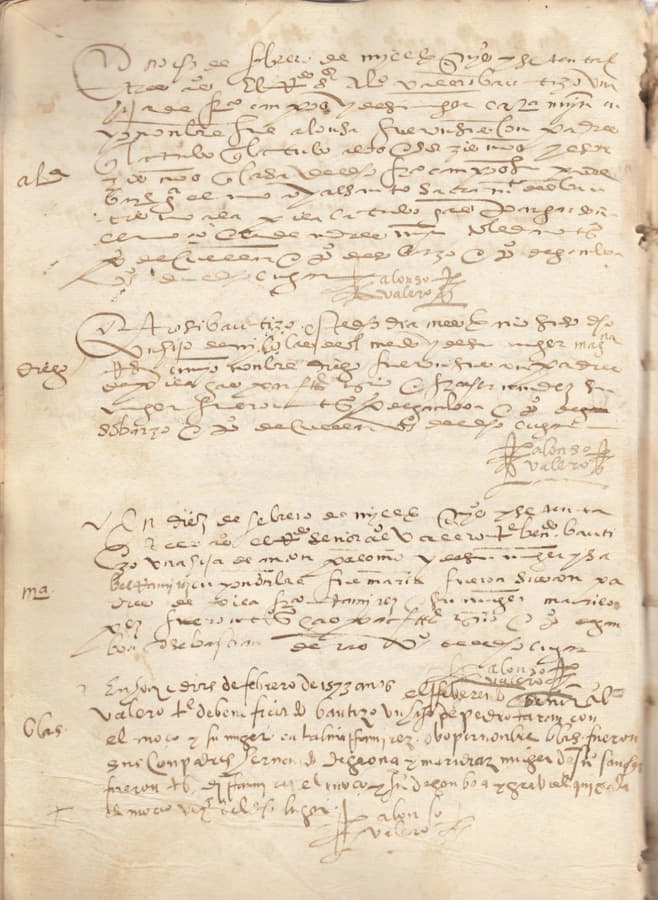

At this point, I must state that Diego Romero has found precise documentation that, between 1577 and 1589, Nicolás de Olmedo hired 20 young girls, all of whom were eleven years old. According to the new document of January 5, 1592, found by Diego Romero, we know that the Council of Esquivias agreed to appoint a new barber officer in this way:

“For being Able and sufficient and having a Letter of Review for such barber by Cristobal Ximenez… And that he be obliged to have knowledge of the Sick that are found in the said place and to walk with the doctor to visit them… that he cannot leave the said place without the License of Justice. That he may not play ball or throw or work with an axe or adze or anything else. And if he should be ill, that he be obliged to have another barber in the place at his own expense, and if he does not do so, that the Council bring another barber at his own expense.” (And it is signed by Nicolás de Olmedo, as a member of the Council).

Thus, from the beginning of January of 1592, the Master Barber, Nicolás de Olmedo, stopped holding the office of the barber’s shop in Esquivias, which then reverted back to Cristóbal Ximénez.

Further, it is worth mentioning that thanks to these new documents, found by Diego Romero in the archives of Esquivias, other native characters have become known, and there is now evidence that some of these were relatives of María de Uxena (Quixote, “Galatea,” 288º, 19), the girl whom Catalina de Salazar y Palacios named as heir. One of the most representative of these characters is the Master Barber, Nicolás de Olmedo.

In addition to this, the investigations carried out by Diego Romero document that Nicolás de Olmedo was married to Magdalena Rodríguez, sister of Catalina Alonso, mother of Ana Rodríguez—who married Juan de Uxena, who were parents of María de Uxena (Diego Romero, Catalina, p. 280), and in turn, Nicolás del Olmedo was the brother of Lucía Romana, who married Martín Alonso, parents of Pedro Alonso (Quixote-V-I; “Galatea,” 290º, 18-19).

In this respect, it is indispensable to emphasize that Nicolás de Olmedo and Magdalena Rodríguez were grandparents of the child Juan, whose baptism, Miguel de Cervantes and his wife Catalina de Salazar y Palacios, on the basis of the good friendship between both families, sponsored, on October 25, 1586.

Add to this that on April 9, 1588, Catalina, together with her cousin, Diego García de Salazar, acted as godparents at the baptism of Susana, the granddaughter of the Master Barber, Nicolás de Olmedo, where, on that occasion, Catalina was identified, in the baptismal certificate, as “muger de Miguel de Cervantes” (wife of Miguel de Cervantes).

Adding to the extensive list of inhabitants of Esquivias, and those related to the Master Barber, Nicolás de Olmedo, Diego Romero has discovered that Magdalena Rodríguez, Olmedo ‘s wife, was the aunt of Juana Gutiérrez (obit October 25, 1604) who was the wife of the Sacristan Mayor, Francisco Marcos, who in turn appeared as witness in the marriage of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra with Catalina de Salazar y Palacios.

It should also be said that Catalina Alonso, the maternal grandmother of María de Uxena, was the sister-in-law of Nicolás de Olmedo, and who, at the time of her death (Documents, 10-IX-1590), named Don Juan de Palacios y Salazar, Catalina’s maternal uncle, as her executor.

In view of this, through the documents revealed, linked to Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra, husband of Catalina de Salazar y Palacios, and the evident relationship that existed between Cervantes and Nicolás de Olmedo, for being contemporaries; in fact, according to Diego Romero, it is crystal clear, based on the legitimate documentation, that for the character of Maese Nicolás, Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra took the person of the Master Barber of Esquivias, Nicolás de Olmedo.

In short, I congratulate the Esquivian historian Don Sabino de Diego Romero for the magnificent discovery of new documents of capital importance about the authentic characters presented in The Ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote de la Mancha for the documented biography of Catalina, the glorious Man of La Mancha, the history of Spain and of Esquivias.

As well, I must emphasize that Diego Romero has discovered the twelfth real character of Don Quixote, after Quijano or Quijada y Quesada, sometimes called Alonso Quijano, protagonist of Don Quixote; the priest Pero Perez; Teresa Panza, wife of Sancho Panza, whom Cervantes calls Juana Gutierrez, Mari Gutierrez or Teresa Cascajo; Sancho Panza; the squire Vizcaíno; Pedro Alonso, also called Pedro Alonso de Salazar; Aldonza Lorenzo; Ricote, the Morisco; Pedro Martínez, Tenorio Hernández, and Juan Palomeque, named in Chapters XVII and XVIII of the first part of Don Quixote.

Without a shadow of a doubt, I thank Don Sabino de Diego Romero for his exemplary and excellent work; and with all certainty these documentary gems will form part of the new book, Documentos de Catalina de Salazar y Palacios (Documents of Catalina de Salazar y Palacios), which currently includes 1700 legal documents, 1350 of which were discovered by our extraordinary and indefatigable author Don Sabino de Diego Romero, President of the Cervantine Society of Esquivias. Congratulations.

Laus in excelsis Deo.

Krzysztof Sliwa is a professor, writer for Galatea, a journal of the Sociedad Cervantina de Esquivias, Spain, and a specialist in the life and works of Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra and the Spanish Golden Age Literature, all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles and reviews in English, German, Spanish and Polish, and is the Corresponding Member of the Royal Academy of Cordoba and Toledo.

Featured: Escrutinio de las Novelas llevado a cabo por el Cura y Maese Nicolás, el Barbero (Scrutiny of the Novels carried out by the Curate and Maese Nicolás, the Barber), engraving by Jérôme David, and published by Jacques Lagniet in Paris, between 1650—1652.