Zionism and its impact on contemporary Israel and Palestine are topics of enormous import and therefore demand careful examination, yet they are widely misunderstood. Zionism is often regarded as a Jewish movement. In fact, the vast majority of Zionists are Christian. Moreover, Christian Zionism is usually considered to be a subset of Zionism. In contrast to this popular misconception, we should understand that Christian Zionism is the majority expression of Zionism; Jewish Zionism is an outgrowth of Christian Zionism. While many consider Christian Zionism to be a phenomenon of the religious right, most Christian Zionists are mainstream, liberal Christians. For example, Reinhold Niebuhr, the iconic twentiethcentury American liberal theologian, was selfconsciously and consistently Zionist throughout his career.

Christian Zionism is generally associated with Christians from the “Christian right,” who are loosely labeled fundamentalists or evangelicals. Sometimes, Christian Zionists are referred to as “the lunatic fringe.” Understood narrowly, Christian Zionists see the establishment of the State of Israel as a necessary step in God’s plan of salvation history. This is the best known form of Christian Zionism. This Christian form attracts the most critical attention, especially from mainstream Christians. However, it represents a distinct minority of Christian Zionists. The popular preoccupation with this select band on the Christian Zionist spectrum ignores the vast majority of Christian Zionists. I will refer to this strain of Zionism as fundamentalist or narrow Christian Zionism. In contrast to this narrow view, Christian Zionism, properly understood, covers a much broader range of Christians.

As a phenomenon, Christian Zionism is older than Jewish Zionism. In 1621, Sir Henry Finch wrote a discourse calling for support for the Jewish people and for their return to their biblical homeland. Further development of its primordial form dates to the first quarter of the nineteenth-century in England and in the United States. In the nineteenth century, Christian Zionism was, indeed, a fundamentalist ideology, but it has spread far beyond the narrow boundaries of evangelicals and biblical literalists. Over the past twenty years, Christian Zionism has attracted more and more scholarly attention, but that attention has been focused almost exclusively on this select band of the fundamentalist Christian Zionist spectrum, leaving wider and more conspicuous bands of the spectrum almost totally ignored—hiding in plain sight. This preoccupation of mainstream Christians with fundamentalist Christian Zionism is both misguided and misleading. Zionism is far more pervasive among “mainstream” Christians than it is usually regarded to be. Christian Zionism is not usually associated with mainstream, progressive Christians. This error needs to be corrected.

Christian attention to the phenomenon of Zionism is appropriate, because, paradoxically, Zionism originated as a Christian phenomenon and continues to be overwhelmingly Christian. How do I arrive at this conclusion?

Estimates of the number and percentages of fundamentalist and/ or evangelical Christians in America vary depending on how one defines these terms, but most surveys estimate that about twentythree to twenty-seven percent of the US Christian population is evangelical.1 In 2014, for example, a Pew Research poll of 35,000 Americans put the Christian population of America at seventy percent (210 million Americans). It found that evangelical Christians make up about one quarter of the Christian population (52.5 million Americans).

By way of contrast, consider that the world’s Jewish population is about 14 million people, i.e., about one quarter of the population of evangelical American Christians. At the risk of oversimplification, but to help demonstrate my point, consider that if all Jews in the world are Zionist, but only half the evangelicals in the USA are Zionist, then American fundamentalist Christian Zionists would outnumber all Jewish Zionists in the world by about 2:1. Thus, even if all Jews in the world are Zionists—and we know this is not correct—and only half of evangelicals in the US are Zionists, then Zionism is an overwhelmingly Christian phenomenon. The ratio of American fundamentalist Christian Zionists to American Jewish Zionists is closer to 5:1. Once Christian Zionism is properly understood

to include many progressive Christians as well, we will see that for every Jewish Zionist, there are at least ten Christian Zionists.

The significance of this point should not be ignored, because Zionist apologists often advance the erroneous and specious complaint that criticism of Zionism is a new and evolved form of anti-Semitism.

Zionism, however, should not be overly identified with Jews and Judaism for a number of reasons, most importantly because Christian Zionists vastly outnumber Jewish Zionists, especially once Christian Zionism is properly understood. Since Zionism has had enormous and far-reaching consequences on a national and global level and because it is overwhelmingly Christian, the examination of Christian Zionism by Christians of all persuasions is an important historical and ethical enterprise. What is more, since Zionism has produced catastrophic consequences for many people, Jews as well as non-Jews, Christian examination of Zionism, especially in its Christian forms, is a moral obligation as well. In any event, Christian examination of Christian Zionism is first and foremost an examination of Christians, Christian ideology, and Christian ethics.

My own consideration of Christian Zionism dates to the mid-1990s, when I was first introduced to it in its fundamentalist form. It was about that time that the phrase Christian Zionism was coined. My first essay on the subject—and I believe the first time the phrase mainstream Christian Zionism was employed and examined—was published in Michael Prior’s last book in 2004. By that time, Christian Zionism had gained considerable media attention, including a thirty-minute segment of 60 Minutes in 2003 and feature articles in the Washington Post and USA Today. However, those segments focused on what we should consider to be only a subset of Christian Zionism (i.e., the fundamentalist version represented by John Hagee, Hal Lindsay, and the International Christian Embassy in Jerusalem). It is also illustrated in the popular Left Behind series of fiction books. Critics frequently refer to this subset pejoratively as a Christian heresy or as the “lunatic ravings” of the Christian right.

Stephen Sizer, an English Episcopalian priest, wrote his doctoral dissertation on Christian Zionism. The dissertation is exclusively preoccupied with evangelical, fundamentalist Christian Zionism, ignoring the dominant mainstream variety, and he continues to focus his critique of Christian Zionism on this subset. In 2012, Steven Paas published Christian Zionism Examined. It focused exclusively on the fundamentalist form. In 2013, Paul Louis Metzger posted at Patheos a critique of Christian Zionism that focused exclusively on the fundamentalist Christian version. In 2014, at a conference on Christians in the holy land, sponsored by the United Methodist General Board of Global Ministries in Ginghamsburg, Ohio, Alex Awad, a Palestinian American Baptist minister, lectured on Christian Zionism. He focused exclusively on its fundamentalist form. David Wildman, also with the United Methodist General Board of Global Ministries, held forth frequently on the topic of Christian Zionism, always in its narrow form.

Fundamentalist Christian Zionism An Easy Target for Liberals

It is not surprising that most contemporary attention focuses on fundamentalist Christian Zionism. Fundamentalist Christian Zionists are vocal and visible, and therefore easily identified. Due to their distinctive and sometimes bizarre biblical interpretations, they are also easily critiqued. Recent popular and scholarly assessments of fundamentalist Christian Zionism are not wrong, but they are misleading. The problem is that defining Christian Zionism as a form of biblical literalism is a mistake. If biblical literalism defines Zionism, then most Jewish Zionists, including the foundational Jewish Zionists, like Theodore Herzl, would not qualify.

That Christian Zionism does not require a fundamentalist reading of the Bible is well recognized by fundamentalist Christian Zionists. The Rev. Malcom Hedding, a spokesperson for the International Christian Embassy in Jerusalem, writes:

If Zionism is the belief in the Jewish people’s right to return to their homeland, then a Christian Zionist should simply be defined as a Christian who supports the Jewish people’s right to return to their homeland. Under this broad and simple definition, many Christians would qualify no matter what their reasons are for this support.

Understood more broadly and more correctly, the ranks of Christian Zionists include renowned mainstream Christians such as Reinhold Niehbur, Krister Stendahl, Robert Drinan, William Albright, and W. D. Davies. Public figures including John Kerry, Hillary Clinton, and the journalist James Carroll must be included among Christian Zionists. None of these are biblical literalists. All of them are Zionists. Further, almost the entire biblical academy is, if not selfconsciously and directly in the service of the Zionist agenda, then at least indirectly engaged in promoting the Zionist narrative. The same can be said for mainstream churches that promote and reinforce the Zionist narrative in their Sunday school curricula, hymnody, and liturgies. Finally, almost all so-called Christian-Jewish dialogue is dominated by sympathy for the Zionist agenda. Indeed, most forms of so-called Christian-Jewish dialogue exclude any consideration of the effects of the Zionist agenda on the peoples of Palestine. Mainstream Christian Zionists are progressive and liberal. They often do not declare their Zionist orientation. Their affinity for Zionism is often masked by a sincere and notable concern to correct past wrongs by Christians against Jews. They usually do not endorse the extreme policies of the State of Israel against the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, although their sensitivity toward Palestinians does not usually include the Palestinian experience in 1948. One might reasonably wonder how Christians can reject on moral grounds the occupation of the West Bank and Gaza in 1967 and its aftermath, but at the same time accept the occupation of Palestine in 1948, which was far more devastating to Palestinians without any moral compunctions whatsoever?

What Then Defines Zionism and How Do We Recognize That It Is Mainstream Christians?

If Zionism does not require biblical literalism in either its Jewish or Christian forms, then what defines a Zionist and Zionism Zionism is a nationalist movement bearing a family resemblance to all other nationalist movements of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries and containing its own idiosyncrasies. Like any nationalist movement, it is subject to critique and it is subject to the same critique to which all nationalist movements must submit. All nationalism is exclusive. All exclusivity is divisive. All divisiveness is unstable. In my opinion, to be clear and in the interests of full disclosure, all nationalism is perverse and anachronistic. The advent of the nationstate is a modern phenomenon that has resulted in unprecedented ethnic conflict and unspeakable and unparalleled violence by peoples against each other. Zionist nationalism is no more violent than, for example, American nationalism, and no less violent, either. While they are different currently, neither is exceptional in that way. It is important to note, however, that people are sympathetic to Zionist nationalism because first they are sympathetic to the concept of nationalism.

There is no simple formulaic definition of Zionism. However, any articulation of Zionism, such as the one above by Malcolm Hedding, must express, one way or another, the ideas that 1) the Jewish people are a distinct people; 2) like other peoples, Jews are, and Jewishness is, best actualized in a nation-state characterized by national institutions and distinct boundaries; and 3) that this organization into a nationstate is not only a political and historical necessity, but a moral imperative as well. None of these essentials is unambiguous and none is beyond question, but whenever you find these ingredients, you will find a Zionist, whether he or she is Christian or Jewish, religious or secular, fundamentalist or progressive. When one considers these three characteristic features—each of which involves elaborate corollaries—one begins to get a feel for mainstream Zionism in contradistinction to fundamentalist Zionism. These three characteristics—that for the Jewish people, the establishment of the State of Israel is both a political necessity and a moral imperative—are common to those who identify themselves as Zionists.

Where do we find exponents of Zionism, so defined, among mainstream Christians? Let’s start with Reinhold Niebuhr, the iconic Protestant liberal Christian. Niebuhr was educated at Yale and wrote prolifically for The Christian Century, The Nation, The New Republic, and his own Christianity in Crisis. He was eventually appointed professor of ethics at Union Theological Seminary. He was by no means a

fundamentalist. There is no hint of any reference to the fulfilment of biblical prophecy in his writings. Indeed, he denigrates such views. Niebuhr’s unwavering support for Jewish causes was nurtured by strong philo-Judaism. He was motivated not by restorationist theology and informed not by biblical literalism, but by moral outrage over the experience of Jews in Nazi Germany and throughout Europe and central Asia. For him, support for the Jewish people required support for the Jewish state and both were moral imperatives. His conscience was attuned to issues of justice and the moral obligation of Christians to respond to social challenges. He spoke frequently in support of Zionism to Jewish audiences. Leaders of Zionist organizations identified him as one who could be counted on to advance their agenda among Christians and he agreed to write a two-part pro-Zionist article that appeared in The Nation. He wrote:

The problem of what is to become of the Jews in the postwar world ought to engage all of us, not only because a suffering people has a claim upon our compassion but because the very quality of our civilization is involved in the solution… The Jews require a homeland…

Clearly, Niebuhr was predisposed by his theological orientation toward empathy for Jews. Just as clearly, he had no interest in fundamentalist biblical hermeneutics. Does that fact alone, however, disqualify him from the ranks of Zionists? On the contrary, his orientation toward Zionism perfectly illustrates that fundamentalism is not a precondition for Christian Zionism. He wrote:

Many Christians are pro-Zionist in the sense that they believe that a homeless people require a homeland; but we feel as embarrassed as anti-Zionist religious Jews when messianic claims are used to substantiate the right of the Jews to the particular homeland in Palestine… History is full of strange configurations. Among them is the thrilling emergence of the State of Israel.

Zionism and the Mainstream Academy

Turning to the arena of Christian biblical scholarship, Christian Zionism is ubiquitous. In recent years, prominent biblical scholars, including Keith Whitelam, Thomas Thompson, and Michael Prior have produced groundbreaking works demonstrating that both biblical archaeology and the broader field of biblical studies are dominated by scholars whose ideas are sympathetic to and have the effect of validating the Zionist enterprise. This is particularly obvious when one travels through Israel, where virtually every archaeological endeavor is pressed into Zionist service to reinforce the Zionist narrative of Jewish return and validate exclusive Jewish claims to the land.

Neil Asher Silberman explores this theme vigorously as it pertains to Zionist historiography. One outstanding example, among many, is the archaeological excavation of Masada. Yigal Yadin, an avowed Zionist who directed the dig and who first published its findings, is the author of the popular myth of Masada. Yadin’s findings and the Masada story were subsequently debunked, but, nevertheless, live on because they fit so well with the worldview of contemporary Israelis. Twenty-five years after Silberman published his work, Christian pilgrims, no less than Israeli school groups, are saturated with the fiction of Jewish Zealots heroically defying overwhelming odds, just as the Israeli Defense Force is said to do today in its aggressive wars of “selfdefense.” Biblical scholars reinforce this link by happily adopting Zionist language of Jewish return to the land. That Jesus and his compatriots, both those who were his supporters and those who were his detractors, belonged to one unified Jewish people is almost uncontested in biblical scholarship. English translations of the New Testament routinely refer to Jesus, his followers, and his opponents all as Jews, even though careful translation of the original languages of the texts would call for more nuanced translation.

Just as astonishingly, modern biblical scholars constantly refer to Jesus or Paul as practitioners of Judaism without nuance. The diversity of conceptions implied by the Greek noun Ioudaios and its cognates is consistently undermined in contemporary Biblical translations. In fact, the contrast between the scarcity of the unnuanced references to Judaism in firstcentury literature and its frequency in contemporary biblical scholarship is striking and well illustrates the degree to which mainstream Christian biblical scholarship helps to cement the connection between modern Zionist Jews and their claim to the territory of ancient Israel. Interpretation matters. Words not only describe reality. Words also condition the way we think about reality. The words biblical scholars use to describe the ancient past promotes an identification of modern Jews with ancient Jews and reinforces the Zionist claim of a direct line between past and present and the natural return of the Jews to their ancestral land. It should be observed that the archaeologists and historians whose historiographies are so harmonious with the Zionist enterprise, more often than not, are Christians who are neither fundamentalist nor dispensationalist.

Zionist ideology depends heavily on the idea of a distinct modern ethnic group which originated in the territory of ancient Israel and which can trace an uninterrupted lineage to ancient Israel. This historical oversimplification undergirds many modern Zionist claims to the contemporary real estate in Palestine. Such Zionism appeals to biblical archaeology to validate its contemporary claims to ethnic identity and territorial integrity. But the scholarship is not merely congenial to Zionist ideology. Biblical scholars themselves often uncritically presume the ethnic identity, territorial legitimacy, and nationalist aspirations at the root of Zionism. If the assumptions of the scholars are identical with those of Zionists, why do we not consider those scholars Zionists?

Mainstream Christian Zionism also pervades one of the most hallowed precincts of liberal, mainstream Christianity, namely so-called Jewish-Christian dialogue. It is no surprise that Jews involved in the dialogue display obvious Zionist sympathies, but their Christian counterparts are often equally and unapologetically Zionist. It is also in this realm that the challenges associated with identifying and critiquing mainstream Christian Zionism are most apparent. Unlike the ranks of fundamentalist Christian Zionists, whose opinions are often shrugged off as “lunatic ravings,” mainstream Christian Zionists are not easy targets. Not only does mainstream Christian Zionism include icons of liberal, progressive Christianity, their motivation for assuming obviously Zionist positions is motivated by and grounded in sincere moral concern.

The reality of Jewish suffering should be prominent in all Christian thinking, but in the formal circles of Jewish-Christian dialogue, it propels Christian participants to adopt clearly Zionist positions. Almost without exception, their concern grows out of sincere regard for Jewish suffering and the demands of justice and restitution. Rarely, however, does their concern extend equally to the Palestinians who experience Zionism as an instrument of catastrophe. One notable example among many is Father Robert Drinan, formerly Dean of the School of Law at Boston College and professor of law at Georgetown University. Drinan was a well-known activist in liberal social causes throughout his long and illustrious career. However, in describing Zionism, Drinan uses language that would have surprised even Herzl, whom, he says, pursued his “messianic pilgrimage” with a zeal “infused with a compelling humanitarianism combined with traces of Jewish mysticism.” The “mystery” and “majesty” of Zionism appears in its glory from Herzl’s tomb. Now that the state is established, Christians should support it “in reparation or restitution for the genocide of Jews carried out in a nation whose population was overwhelmingly Christian.” Let’s not ignore Father Drinan’s distinguished ten-year career as a member of the US House of Representatives (DemocratMassachusetts), during which he had numerous opportunities to express his enthusiasm for Zionism by voting in favor of legislation and resolutions that were staunchly pro-Israel. He is, thus, also an example of the way in which mainstream Christian Zionism pervades US political institutions.

Conclusion

Very few topics generate fervent debate, arouse passions, and evoke confusion like the IsraeliPalestinian conflict. This is because it veers into the volatile areas of religion and politics. Personal faith, interpretation of scripture, personal loyalties, moral convictions, and deeply-held political opinions overlap and collide in a confused sea of facts, perceptions, images, and realities. Notwithstanding these treacherous emotional waters, conscientious American Christians have no choice but to attempt to navigate them, because their churches and their government are both deeply complicit in the sadness and suffering of the people of Israel and Palestine.

In spite of the often repeated critiques of fundamentalist Christian Zionism, a more pervasive, pernicious, and sophisticated form of Zionism has been overlooked. I call it mainstream Christian Zionism. I believe that most American Christians should be included in this category. But if only half of mainstream American Christians are Zionists, then mainstream Christian Zionists outnumber American Jewish Zionists by 14:1. Were it not for this form of Christian Zionism, the more easily identifiable, easily critiqued, unsophisticated form of Christian Zionism would not have the effect that it has. The minority wields great influence and exerts great energy, but they still need the majority to effect policy and the majority is only too happy to play its part. Mainstream Christian Zionism does not depend on biblical authority for its legitimacy. It is rooted in genuine moral sensitivities. Its appeal is to moral imperatives and political necessity rather than personal piety. It assumes uncritically that nationalism is natural and necessary and so starts with a predisposition to Jewish nationalism. It is far better organized, far better funded, and far more politically potent than its

fundamentalist cousin

Reconsidering Christian Zionism in its mainstream form leads inevitably to vexing moral conflicts. It requires re-examination of widely held assumptions about ethnic identity and nationhood and the moral implications of these. It raises issues that are considered taboo in the Church and takes us into perilous moral and academic “no-fly zones.” But intellectual honesty requires no less.

It is, of course, quite convenient for mainstream Christians to identify Christian Zionism exclusively with evangelical, fundamentalist Christians. It is always easier to identify other people’s defects than one’s own. Mark Twain reportedly once said, “Nothing so needs reforming as other people’s habits.” Jesus said, “First take the log out of your own eye…”

Mainstream, liberal Christians cannot absolve themselves of complicity in the Zionist enterprise simply because they are not fundamentalists. If they espouse views that are identical to the nationalist assumptions of self-confessed secular and religious Jewish Zionists, then they themselves should be identified as Zionists.

Equating Christian Zionism so thoroughly with evangelical, fundamentalist Christians, or with the Christian right, is highly misleading, and ignores the reality that Christian Zionist support for the State of Israel comes overwhelmingly from mainstream Christians. Until we understand Christian Zionism in its mainstream aspects, however, we have not begun to appreciate how pervasive—and, therefore, how dangerous—Zionism really is.

Peter J. Miano teaches courses in New Testament studies, biblical archaeology, biblical geography and biblical history. He also teaches courses in missiology. He specializes in the history of the Middle East, its contemporary development and the role of the Church in the Middle East during the 19th, 20th and 21st centuries.

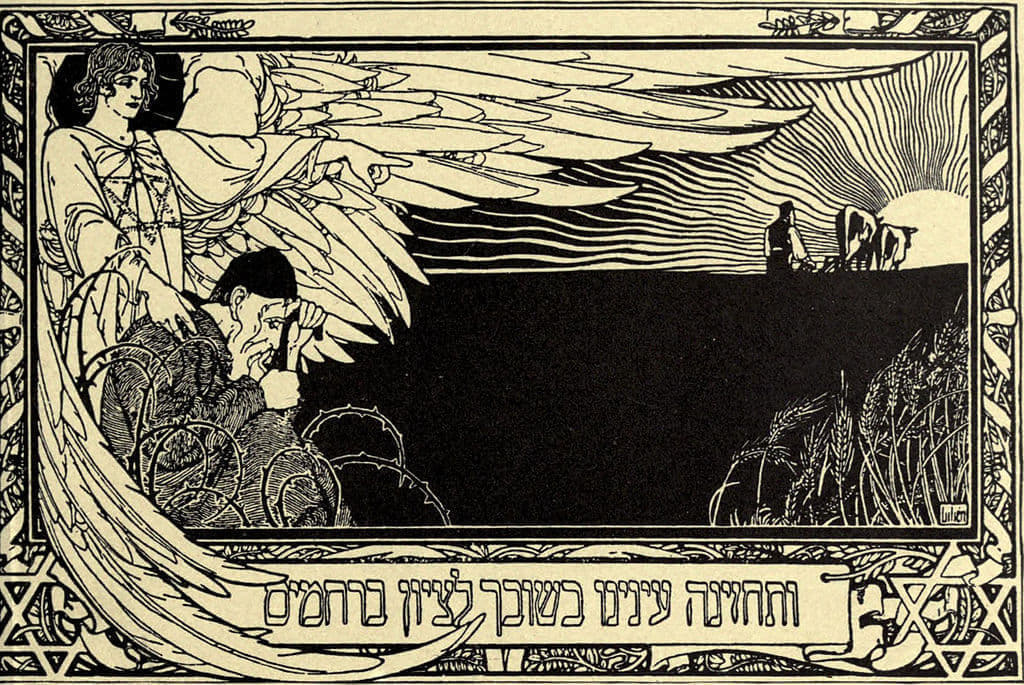

Featured: Engraving by Ephraim Moshe Lilien, produced for the 5th Zionist Congress, which took place in Basel, Switzerland in 1901. The Hebrew inscription at the bottom is the prayer “May our eyes behold your return in mercy to Zion.” This is an excerpt from Prophetic Voices on Middle East Peace.