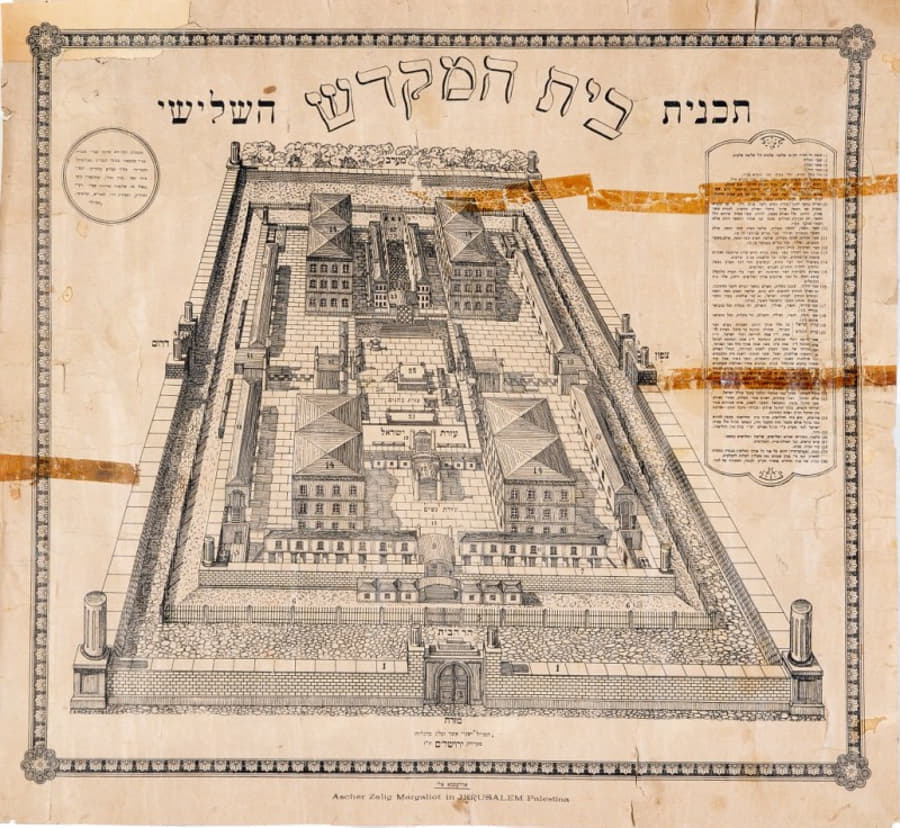

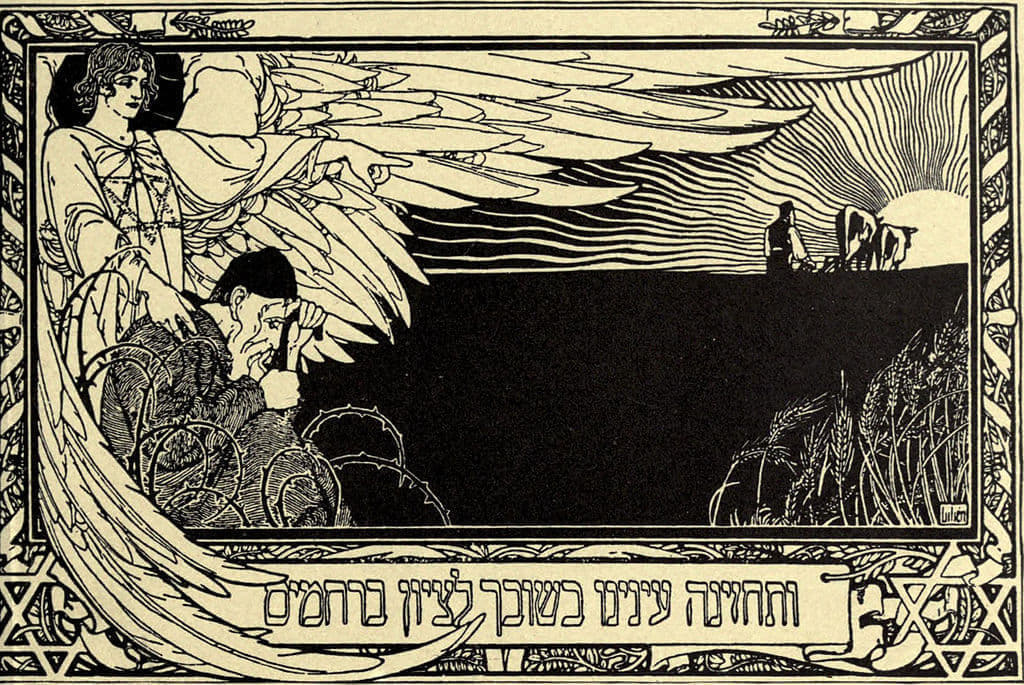

Why does Israel need to exist? This question may seem startling and unfair, but it is one that is frequently asked and hotly debated. The various answers and arguments given fall under two categories. First is the political and somewhat historical answer, which argues that the Levant is the Ur-Heimat of the Jews and thus for Jews to settle there is not only natural, but an unquestionable (God-given) right, as it is simply reclamation of legitimately owned property, and it is the Palestinians who are recent interlopers. Here it is important to note that the vast majority of the land itself inn Israel is owned by the state, and thus reserved for Jews, which means an exclusion of Palestinians. The second answer expands on this approach and seeks to bolster it by veering into the mystical and the messianic: Israel must exist because it is the necessary condition for housing the Third Temple, which in turn will bring the messiah and his “golden age.” This second answer brings together the aspirations of Protestant and Jewish Zionists. Both answers, sadly, also inform much of the anti-Arab sentiment that pervades the powers that be in Israeli society: the land does not really belong to Palestinians; the Jews, as God’s chosen people, must do what God needs them to do: build the Third Temple so that the age of the messiah can begin.

The Misuse of History

Turning briefly to the first answer—can we really locate the ancient Hebrews in Palestine? With the Bible within easy reach, this question may come off as impertinent. But it is a very important question—one which scholars have long fought over, from the 17th century down to our own time, and one which has not yet provided a real answer. A related question is just as important—is the Bible a book of history or a book of faith? Or to put it more clearly, is the Bible the ancient history of modern-day Jews?

It is also often said that the Bible is our best guide to the ancient Judaic past, but when we come to write such a history how do we distinguish between literary commentary on, and literary convention in, the various books of the Bible and the historical process itself, that is, a historical reconstruction of what precisely took place thousands of years ago? The Protestant sola scriptura habit of mind is at play here, in that everything found in the Old Testament can be located in the Levant; it is only a matter of finding it; there is never any need for subtlety or nuance (the quadriga), for theology is a mirror of politics and the Bible can only mean what an immediate reading yields. It was American Protestants who began archaeology in the Holy Land in earnest, in the 19th century, to counter the rising arguments of skeptics, and the role of American Protestants has not diminished.

More importantly, all this is not to say that the Bible is therefore fiction—but rather to point out that we are dealing with faith-based commentary of various historical events. Understanding those events—and events that have been left out—entails historical fact, to which we have limited access, and to which faith commentary is of limited use. The Bible is not a history textbook, although it contains actual history. By this we mean that history recounts the deeds of the men and women of the past and their ensuing consequences, while the Bible selects events to show cosmic significance. In other words, history sees a text as artifact, while the Bible seeks to show the ways of God to man. Thus, archaeology in the Holy Land continues to show a divergence rather than a coalescence, which means that the Bible is a product of ancient Judaean life rather than a guidebook to it.

Because archaeology and the study of ancient history are highly contentious disciplines in Israel, the field has long adopted two categories to immediately label scholars: there are the “maximalists” and the “minimalists.” The former seek to find an exact replica of the Bible in the dust of centuries and in extra-Biblical written sources. The latter fail to see such a replica in what is found in the ground and what is written in ancient texts. Needless to say that these are effective policing strategies fo scholarship, whereby the maximalists have the the megaphone (funding, media coverage, the American Protestant audience), while the minimalists are simply ignored because they raise questions that are not so easily answered. In the popular American Protestant mind (the true power base of Israel), the “Word of God” is a grand code-book that needs constant reconfiguring in order to learn what will happen in the future (the End Times), and thus faith simply means participating in this deciphering process. History is just another tool for this prodigious decoding, in which minimalists are “atheists” or secularists.

The Curse Tablet

As can be imagined a lot of deceit, or trickery, is involved in the maximalist camp. A recent example comes from Marcg 2022, when a dramatic announcement was made that a small curse tablet had been found in the Palestine territory (on Mount Ebal). The archaeology was done by Associates for Biblical Research, a Protestant ministry, which seeks to bring the Bible alive and which therefore publishes a magazine called, Bible & Spade.

The tablet measures just one square inch, and it was found under very suspicious circumstances—in the left-over rubble from a previous excavation, done in the 1980s, and during a supposed archaeological expedition that did not have any of the proper authorization from the Department of Antiquities of the Palestinian Authority, and the Israel Defense Forces’ Civil Administration, which controls this area, referred to it simply as “private activity”—hardly a scientific expedition. This means that first there is no way to date the tablet (since it has no context in which it was found), and second it is an illegal find since it was taken away without authorization. Two huge red flags.

Then, came the huger claims by the two discoverers.

Scott Stripling declared: “One can no longer argue with a straight face that the biblical text was not written until the Persian period or the Hellenistic period, as many higher critics have done, when we clearly do have the ability to write the entire text [of the Bible] at a much, much earlier date.”

Then, the needed affirmation by Gershon Galil of the University of Haifa: “The scribe that wrote this ancient text, believe me, he could write every chapter in the Bible.” Galil is known for finding dubious artifacts.

Why is it that the Bible needs the work of very amateurish (at best) “scholars” to “prove” its truth?

And the claims continued to grow in their wild-eyed exuberance. The tablet “proved” the “truth” of a ritual curse ceremony on Mount Ebal described in Deuteronomy 27:9-26 and Joshua 8:30-35. Plus, given the “fact” that the writing on the tablets is Hebrew script, therefore, the books of the Bible were written much earlier (the date of the tablet, which is claimed to be 1300 BC).

But then reality hit. When the team finally published the supposed Hebrew writing, it was from inside the tablet (it is a piece of lead, folded in half); they say that there is also writing on the outside which is easier to read. The photos shown just show a few indentations, which the duo have “read” as the entirety of the Hebrew alphabet. Professor Christopher Rollston, an expert in Northwest Semitic languages, at George Washington University, gave the funeral oration: “The published images reveal some striations in the lead and some indentations (lead is, of course, quite soft and so such things are understandable), but there are no actual discernible letters.”

In other words, more pareidolia.

The most amusing example of such efforts is the discovery earlier (March 2023), which again was announced in the media with great excitement. It seemed that Eylon Levy, international media adviser to President Isaac Herzog, while out for a hike, had found something unique: direct evidence of the Persian King Darius inside Israel. The text scratched on to a potsherd was rather cleanly written in Aramaic, and read, “Year 24 of Darius.” More proof of what the Bible says, etc.

Then, it came out that it was simply a piece of broken pottery on which a professor had written this brief text, to show to her students how and why ancient ostracon were created. After the demonstration, she just tossed aside the piece of pottery, not thinking that it would be found and “read” a certain way. The scholarly world did some quick damage control.

Because reports of such “discoveries” have only grown in number, serious Israeli scholars were finally forced to issue a public statement, a request to tone down the claims and let real scholariship do its job.

The Bible and Nationality

Thus, is it really historically feasible to use the Bible to justify national interests in the here-and-now; to say that the Jews of today are the direct descendants of the Hebrews mentioned in the Bible? People like Stripling and Galil and their Zionist Protestant supporters would say, absolutely!—which can only be matter of personal belief rather than an affirmation based on data (and when such data does come up, it is sketchy at best). This sort of encounter with history too stems from the sola scriptura habit of mind which is accustomed to approach the Bible out of context—an amateur’s eisegesis, as if the Bible were a book being read by students in a high school English class.

However, putting aside the Bible, we only have sporadic archaeological attestation for Judaism, as such, in ancient Palestine: the harder we look for the acient Hebrews of the Old Testament, the more quickly they vanish in the actual historical record—which renders the historical claims of ownership of the Holy Land very problematic, more so when we throw into the mix notions of race—that modern-day Jews are direct descendants of the people inhabiting the Old and New Testaments. Thus, writing the history of the ancient Hebrews as Israel and Judaea (for there were two kingdoms) comes out more often than not as the history of ancient Palestine, in which Canaanite and Hebraic elements are impossible to distinguish.

This is not to say that Canaanite and Hebraic people did not live in the region; rather, how does the life of these ancient people become that of the people in the Bible?

Dome of the Rock

The second answer brings into focus the Al-Aqsa compound, which now is also called “the Temple Mount” by the Israelis. The entire complex, known as Haram Al-Sharif (the Sacred Enclosure) covers some 35 acres (a sixth of Old Jerusalem) and includes other mosques, prayer halls, and various Islamic religious structures. The compound also contains one of the holiest cemeteries in Islam, the Bab al-Rahmah (Mercy Gate), where many Muslim notables lie buried. The term “Temple Mount” is a revival of a term used in the Middle Ages by the crusaders who called this area, “templum Domini” (Temple of the Lord), but they were likely seeing a church built by Saint Helena.

The Dome of the Rock itself, as a building with its distinctive golden dome, is somewhat mysterious in its origins, as it only became associated with Muhammad’s Night Journey to Jerusalem sometime in the 11th century, and only became a mosque proper in the 13th century. The original distinct structure, which now has a golden dome, was likely built late in the 7th century (694 AD, according to the inscription inside), although what we see today is largely 20th century renovation.

We also know that Saint Helena built a domed church in the area (dedicated to Saint Stephen), which is visible in the Madaba Map (6th century). Thus, the Dome of the Rock likely began life as a Christiano-Arabic church, in the Syro-Byzantine style, for it is extremely similar to other churches of that era, both nearby and further afield, namely, the Chapel of the Ascension in Jerusalem, the Mary Theotokos Church at Mount Gerizim near Nablus, the Church of the Seat of Saint Mary (which also encloses a rock). And the Dome of the Rock is also akin to the Little Hagia Sophia (church of Saints Sergios and Bacchus) in Istanbul, the church of San Vitale in Ravenna, the Palatine Chapel of Aachen, built by Charlemagne, and the church of Las Vegas de San Antonio, in Pueblanueva, Spain.

The key feature of all these Byzantine churches (which includes the Dome of the Rock) is their octagonal shape. The number eight in Christian eschatology signifies the first day after Christ’s Resurrection, that is, after the Sabbath (the seventh). Thus, in Christian tradition, the number eight signifies completion, wherein the faithful were made complete by being resurrected into Glory with Christ.

All this also takes us back to the early history of Islam itself, which has been thoroughly explored and clarified by the scholars at Inarah. In brief, Islam is best understood as a distinct anti-Trinitarian Christology. There were several such Christianities current in the East before the 11th century, all of which eventually came to be codified into what we now call “Islam.”

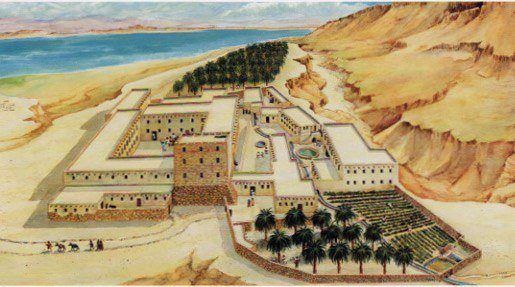

Thus, in effect, the Dome of the Rock has a precise and distinct Christian and Islamic history. What it does not have, however, is a clear and precise Jewish history. There were likely buildings here from the time of Herod the Great, such as the Esplanade, which is thought to be the encircling wall of Herod’s renovation of the Second Temple, but no clear written history exists that pins down this association with Herod’s renovation of Solomon’s original temple; nor are there any remains at the Al-Aqsa complex (thus far) that might offer evidence of an ancient Hebrew ritual presence . Attempts to align the Temple Mount with what Josephus describes are unconvincing and precarious at best and often a matter of personal opinion of the historian. The archaeological work done in the area has yielded Christian and later Islamic artifacts and buildings (what is known as the “Umayyad palace”). The only thing that is said to be from the time of Herod are the many cut stones, but are they from the Second temple? There are also other artifacts which have been found elsewhere in Jerusalem, such as the two Temple Warning inscriptions. Again, to link these exactly to the Temple Mount is difficult to sustain. As well, there is big problem with forgeries.

As is often the case, when doing archaeology with Bible in hand, the yield is always disappointing. The ancient Hebrews of the Old Testament simply vanish in the dust of Palestine and are impossible to trace. History is very precarious work in Israel, because it is so highly political, for its goal is often nationalist: to prove that Palestine was always Jewish, so the further back in time we go, the more evidence there must be of a persistent and obvious Hebrew presence. That has not happened.

The Wailing Wall and the Second Temple

As for the Western (or Wailing) Wall, it is difficult to say that it is definitely a remnant of Herod’s Second Temple. More than likely it is a wall from the Antonia Fortress of the Romans. It is only assumption that links the Western Wall to the Second Temple. The many points of evidence presented are “readings” of artifacts, readings preconditioned by politics: there can be no neutral, impartial history in Israel when it comes to the issue of the location of the Second Temple. Only the bottom stones, it is said are Herodian and therefore from the Temple; the top part is later Islamic.

The tradition of praying at the Wall is also very late (16th century). For example, the very detailed account of the Temple site, written in 1267, by Nahmanides (in a letter to his son, Nahman), makes no mention of the Wall at all. In the 14th century, Ishtori Haparchi also seems unaware of it, and we further find no mention made in the various accounts from the 15th century, such as, by Obadiah of Bertinoro. It is only with the coming of the Zionists in the 19th century that the Wall became closely associated with the Second Temple and became a holy site. In fact, Baron Rothschild offered to buy the entire Al-Aqsa area; his plan was to demolish all the buildings on it and build the Third Temple. For various reasons, the plan never came to fruition.

There is also the problem of water, since the only source for it in ancient times was the Spring of Gihon, which is nowhere near the Al-Aqsa compound, and the Temple would have needed a lot of it for various ritual purposes. The compound instead has remains of Roman water cisterns (37 in all) and pools, which are “read” as mikvehs to substantiate the existence of the Temple.

There is also the textual consideration. We are told about the Roman destruction by Josephus who was an eyewitness to it and who tells us that nothing was left standing. All of Jerusalem was completed razed to the ground. Why would the Romans leave the wall of the Second Temple standing when they knew that said Temple was the very heart of Judaism, because of which the Judaeans had fought two bitter wars with them? To leave standing any remains of such an important culti center would only be inviting more trouble. But the Romans would also not destroy their own fortress.

In short, wherever the Second Temple might have been in Jerusalem (likely on Mount Ophel), it could not have been on what is now called “Temple Mount.” Only 19th and 20th century custom has established such a connection, which archaeology and history now seek to confirm. Some even say that the city of David could not have been located on the Mount, which again calls into question the Temple’s location.

If one questions the veracity of the Wall today, one will called a “Temple denier,” which is akin to “Holocaust denial,” and to question the narrative of Al-Aqsa as the location of the Second Temple is to be a Palestinian apologist. In this way scholarly conformity is assured, since the official task of the historian in Israel is to confirm the eternal possession of the Levant by the present-day Jews, and the erasure of any other memory (Christian and Muslim).

Some scholars even doubt that ancient Jerusalem truly has a Hebraic identity further back from the Roman period. But he who “controls the present controls the past.” Antiquity is a source of great power in Israel.

Featured: Samson carrying the gates of Gaza; Huqoq synagogue, 5th-century.