Recently, Jared Kushner, came to his alma mater (Harvard) and gave a lengthy interview to Professor Tarek Masoud, in which he laid out his views on the Middle East.

This interview has been largely derided and thus dismissed or defended. But such attitudes are deceptive. Kushner wields much power and influence and will wield a lot more should Donald Trump again become president in November 2024—he is being touted as Trump’s Secretary of State. We need only recall that Kushner put in place the Abraham Accords, which were devastating for Palestine, but great for Israel.

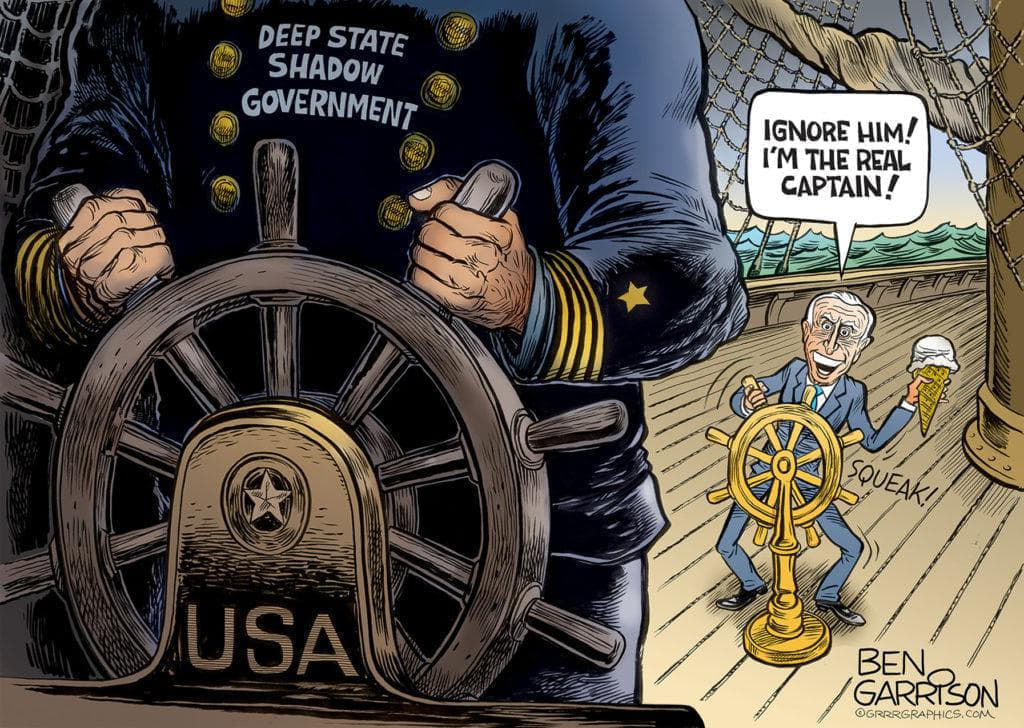

Therefore, his words should be seriously studied, because they form a blueprint of what a new Trump administration will seek to accomplish in the Middle East—which in a nuthell will be to ensure that Israel is the sole master of the region. To bring this about, American effort will be to destroy Iran, ravage Russia and lay waste to China. These three countries are said to support actors hostile to Israel and thus to America. This is made clear by Kushner. The expected, larger outcome is the usual one—the world run by the USA, with Israel in its habitual role of “enforcer,” and Saudi Arabia ever the loyal lackey, with the various lapdog Gulf States in tow.

Over the course of his commentary, Kushner affirms that Israel indeed has nuclear weapons. Of course, Israel is not supposed to have them, but it is also an open secret that they do.

As for the Palestinians, Kushner reasons that it is hard to tell who is a terrorist among them and who is not. Therefore, they need a strong master to manage them; they are too childish to look after themselves. (Here Kushner’s “role” as a father is key). Kushner understands perfectly what is best for the Palestinians, because “father knows best.”

As for a Palestinian state, Kushner calls it a “super bad idea”—because that would be “rewarding” “bad behavior” (something that Kushner would never do as a Dad). Irresponsible children cannot run countries; more crucially, he sees a Palestinian state as a threat to Israel. That can never be allowed. Besides, if given such a state, the Palestinians would just blow it all up anyway. Better that they stay under the sure hand of Israel and somehow make lots of money. Making lots of money is the moral compass that governs Kushner’s International Relations. Genocide? What genocide? Despite being a father, he has nothing to say about the slaughter of children now being carried out by Israel. To further the cause of “Israel über alles,” the suffering of the Palestinian people can never be acknowledged. Kushner’s best suggestion is that the whole lot of them be transported out and put into some place “bulldozed” into the Negev desert. Out of sight, out of mind.

Behind Kushner’s boyish phraseology hides a grim program, in which the cheery wheeling and dealing is meant to destroy all of Israel’s perceived enemies, no matter who has to suffer in the process (the Palestinians, Iran, Syria, Yemen, Egypt, Jordan, etc.). In other words, yet more of the master-slave “paradigm” (a word much used by Kushner). The Middle East must belong to Israel, and thereby the USA. It cannot belong to the majority of the people who actually live there.

In the interview, there is no awareness at all of BRICS and multipolarity, let alone the full aspirations of peoples and of nations. There is only the drive for dominance, all packaged as breezy arrogance which demands that the world be run the American way—or else. This is Kushner’s “deal;” it will be the new Great Game of International Relations, should Trump become president.

Thus, we thought that it important to provide a transcript of this interview that it might be the more thoroughly studied, since the written word allows for deeper reflection rather than a video.

Middle East Dialogues. February 15, 2024

Tarek Masoud: All right. Good evening, ladies and gentlemen. It’s a great pleasure to welcome you this evening. My name is Tarek Masoud. I am a professor of public policy here at the Kennedy School, and I’m the faculty chair of our Middle East Initiative. It’s really my great pleasure to welcome you to this first in our spring series of what we are calling “Middle East Dialogues,” which are a series of conversations that I’m having with individuals whom I believe hold varied and vital perspectives, not just on the conflict in the region, but on the paths towards a more peaceful and prosperous future for the people of that part of the world.

Our guest this evening is one of the few people on the planet who doesn’t need an introduction, and that’s Mr. Jared Kushner. He was a senior advisor to President Donald Trump from 2017 to 2021, where he handled a number of vital portfolios from prison reform to trade agreements with Canada and Mexico, to our response to the COVID-19 pandemic, to the reason that we are here tonight, which is peacemaking in the Middle East.

When I put together this series, Jared Kushner’s name was the very first name on my list, and that’s because he was the architect of the Abraham Accords, which I personally believe to be one of the most significant developments in the Middle East in recent memory. And he’s just generally a deal-maker par excellence. And if there’s any part of the world that I think needs really excellent deal-makers right now, I think it’s the Middle East. So I’m honored that he accepted my invitation to return to Harvard, his old stomping grounds, to have an open and candid conversation about some of the toughest issues on the planet right now.

So, here’s what we’re going to do. We’re going to talk for about 45 minutes, and then we’ll take questions from my students who I will call on. Those of you who know me know that you should never put a middle-aged Egyptian male in charge of timekeeping. So, I’m going to try to keep everything on time so that we can end at the appointed hour. So, first, ladies and gentlemen, please join me in welcoming Jared Kushner.

Humanitarian Toll in Gaza and Views on Immediate Ceasefire

Jared, thank you so much for being with us. So, I just want to dive right into the war on Gaza.

We all know of the gruesome terrorist attack that happened on October 7th: more than 1,200 innocent Israelis brutally murdered by Hamas terrorists, more than 200 people taken hostages. Prime Minister Netanyahu vowed a fearsome military response, which was designed or intended to make sure that this never happens again. Now, today, four months later, more than 25,000 Palestinians are dead. I can’t tell you what percentage of them are Hamas terrorists, but we know that half of them are women and children. We know that more than a million Gazans are trying to shelter in the south of the country. They’re amassing on the border with Egypt. Many reports indicate that Gazans are now enduring a famine, and Israel is poised to begin a ground operation in Rafah that we think will take many more civilian lives. We know Israel’s being accused of genocide in front of the International Court of Justice, and even President Biden says that the Israeli operation has been over the top. But I’m guessing you don’t support calls for a ceasefire, and I wanted to ask why.

Jared Kushner: Jump right into it, so it’s good. First of all, it’s really great to be here, and thank you for putting on this dialogue on the Middle East. I think it’s a topic that I spent a lot of time, I spent four years working on, when I was in the White House. It wasn’t an issue that I had a lot of experience with, so I really came into it with a blank slate. I wish I’d been in some classes like this and gone to lectures like this when I was at Harvard. Maybe it would’ve actually given me a worse outcome, but…

Tarek Masoud: Wait a minute.

Jared Kushner: But I hope today I’ll share with you some of my experience and perspectives. But I will say that, throughout my time, I was always, a lot of the things that I would say, a lot of the things I would do were fairly heavily complained about or criticized from, I would say, the consensus thinking.

So, I think that, number one, when looking at the current situation, I try to look at everything kind of first principles and I try to say, “What’s going on? What should it be? What are the right actions?” And what I find is that there’s a lot of emotion with this issue. Some of it justified, some of it unjustified for a whole host of it. What I would say is this: I think that, number one, I take a step back and say, “Why are we here?” You go back to 2021, and when I was able to go back to my normal life after leaving office

or four years in service, we basically left the Middle East where it was very calm, right? It was calm, it had momentum. You think about ISIS, they were basically, the caliphate was gone. Syria, the Civil War had mostly stabilized in the sense that you didn’t have to think 500,000 people were killed.

When we started, Yemen was destabilized, Libya was destabilized. ISIS had a caliphate the size of Ohio, and Iran was flushed with cash. They were basically using that money to fund Hamas, to fund Hezbollah, to fund the Houthis, and they run a glide path to a nuclear weapon.

So, we inherited a really, really bad hand. And then with the JCPOA agreement, which was probably one of the dumbest agreements I think ever negotiated, just as anyone who studies agreements and deals, that really left us in a bad situation. So, we worked hard. We tried to regain trust. We did a lot of work. And we could talk about that later.

But the way we left the region was basically, we had six peace deals in the last six months that we were there, less, I think in the last maybe four or five months that we were there.

So, we took a different approach to the Palestinians. We were able to make peace between Israel and the United Arab Emirates, and then with Bahrain than Sudan, then Kosovo was able to recognize Morocco. And then finally, we resolved the GCC dispute, which put everything on a pretty good glide path. Iran was basically broke. They were out of a foreign currency reserves, which meant that no money was going to any of these terrorist organizations.

And then in addition to that, the Palestinians basically were out of money too. We’d stopped funding UNRWA. We saw that UNRWA was basically taking the money that we were giving them to the United Nations. It was taxpayer dollars that we were giving to United Nations. We thought it was going to fund terrorists, to give them energy, to give them resources.

We saw a lot of their schools, and their mosques were basically where they would hide the bombs and the missiles and their munitions. And we thought the education that they were giving was really a very, very poor education that was radicalizing the next generation. So, we said, “Okay, there we go.”

So, basically, we thought that the right thing to do basically was to stop funding that, and that was the way that we wanted to kind of advance. So, we went forward, we were able to create the peace deals.

Then you kind of move forward in the region, three years, we thought that Saudi had the ability to do a normalization deal, and we had worked with the Biden administration in order to help them get that pathway, to follow the pathway that we were in.

So, now you forward three years, you have the attack, which was awful. Through not enforcing the sanctions on Iran, they were able to get funding, which they were able to then give to all these different groups. You saw a lot more rise up in the extremism. And I think that America not standing with Israel in the way that they should be led to a lot of this occurring. So, you have a situation now where Israel has the right to defend itself, right? They’re in a position where they had a brutal attack. I mean, imagine America, somebody coming over the border, brutally raping, killing civilians, doing all these different things. I mean, that’s something that I think would be quite horrific for a lot of us. And then I think the sentiment was basically, how do we put this in a position where we attack back? So, I think that what Israel’s done is they’re saying, “How do we secure ourselves this doesn’t happen again?”

Obviously one death is too many deaths. You don’t want any deaths in Israel. You don’t want deaths of Palestinians. But I think right now, the situation is a complex one. But I do hope that with the right leadership, they’ll be able to find the right way to get it to a better place.

Ideas for Ending the Crisis

Tarek Masoud: This was great, because you definitely preempted one question that I was going to ask you, which was, President Trump has been saying that this would never have happened on his watch. But before we get to that, I just want to think about this problem for a minute. One thing I associate Jared Kushner with is creative deal-making, thinking outside the box. Do you have a proposal or an idea or a sketch for how we end this crisis?

Jared Kushner: Sure. So, I think that the dilemma that Israeli leadership has right now is, do you do a short-term deal that leaves you more vulnerable in the future? Or do you take this current situation and try to figure out a way where you can create a paradigm, where your citizens will be safe and this will not happen again? So, it’s a very, very tough dilemma to be faced with if you are the leader of a country.

So, what I would do right now if I was Israel is, I would try to say, number one, you want to get as many civilians out of Rafah as possible. I think that you want to try to clear that out. I know that with diplomacy, maybe you get them into Egypt. I know that that’s been refused. But with the right diplomacy, I think it would be possible.

But in addition to that, the thing that I would try to do if I was Israel right now is I would just bulldoze something in the Negev. I would try to move people in there. I know that won’t be the popular thing to do, but I think that that’s a better option to do so you can go in and finish the job.

I think there was one decision point they had. Do we go into Gaza? Do we not go into Gaza? They had the hostages. There really was, I think, no choice but to do that. I think that they were smart to go slowly and deliberately. Gaza is a booby trapped like crazy; they have over 400 miles of underground tunnels.

So, I think that they’ve taken some of the right steps in order to go there but you have to, again, I think Israel’s gone way more out of their way than a lot of other countries would to try to protect civilians from casualties. But I do think right now, opening up the Negev, creating a secure area there, moving the civilians out and then going in and finishing the job would be the right move.

Ideas for Sheltering Palestinians from Gaza Bombardment

Tarek Masoud: Is that something that they’re talking about in Israel? I mean, that’s the first I’ve really heard of somebody, aside from President Sisi suggesting that the Gazans who are trying to flee the fighting could take refuge in the Negev. Are people in Israel seriously talking about that possibility, about hosting Gazan refugees

in what is considered “Israel proper?”

Jared Kushner: I don’t know. I mean…

Tarek Masoud: But that would be something you would try to work on?

Jared Kushner: I’m sitting in Miami Beach right now, and I’m looking at this situation and I’m just thinking, what would I do if I was there? Again, you look at, I mean, with Israel it’s a different thing. In Syria when there’s refugees, Turkey took them, Europe took them, Jordan took them.

For whatever reason here in Gaza, there’s refugees from the fighting from an offensive attack that was staged from Gaza, Israel’s going in to do a long-term deterrence mission, and it’s unfortunate that nobody’s taking the refugees. Again, I think that the American government should probably have done a little bit of a better job to find a solution to that. As a broker, I think that there would’ve been a way, but if that’s not a viable option, I think from Israel’s perspective, it’s just something that should be strongly considered.

Fears that Netanyahu will not allow fleeing Gazans to return

Tarek Masoud: Yeah, yeah. I mean, obviously the reason they’re not, for example, the reason the Egyptians don’t want to take the refugees in addition to, of course, there being the domestic unrest that could result or the instability that could result, but also there are real fears on the part of Arabs, and I’m sure you talk to a lot of them who think once Gazans leave Gaza, Netanyahu’s never going to let them back in.

Jared Kushner: Maybe, but I’m not sure there’s much left of Gaza at this point. So, if you think about even the construct like Gaza, Gaza was not really a historical precedent. It was the result of a war. You had tribes that were in different places, but then Gaza became a thing. Egypt used to run it, and then over time you had different governments that came in different ways. So, you have another war. Usually when wars happen, borders are changed historically over time.

So, my sense is, is I would say, how do we deal with the terror threat that is there so that it cannot be a threat to Israel or to Egypt? I think that both sides are spending a fortune on military. I think neither side really wants to have a terrorist organization enclaved right between them.

Gaza’s waterfront property, it could be very valuable to, if people would focus on building up livelihoods. You think about all the money that’s gone into this tunnel network and into all the munitions. If that would’ve gone into education or innovation, what could have been done.

So, I think that it’s a little bit of an unfortunate situation there but I think from Israel’s perspective, I would do my best to move the people out and then clean it up.

But I don’t think that Israel has stated that they don’t want the people to move back there afterwards.

Should the US Recognize a Palestinian State

Tarek Masoud: Yeah, yeah. I mean, okay, there’s a lot to talk about there. The last thing I wanted to just get your reaction to on this is the… you saw Tom Friedman’s column on Tuesday about where he put forward a plan to get out of this, and it’s called, “Only MBS and Biden can Redirect the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict.” He says, “Biden should recognize the Palestinian authority unilaterally as a state, and MBS should go to Jerusalem like Egyptian President Anwar Sadat did in 1977. He should say, I’ll normalize with Israel. I’ll recognize West Jerusalem as your capital, and I’ll even pay to rebuild Gaza if you recognize a Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital.” What do you think? Good idea?

Jared Kushner: No, I don’t think that’s a good idea. I think that there’s certain elements of it that are correct. I think proactively recognizing a Palestinian state would essentially be rewarding an act of terror that was perpetrated to Israel. So, it’s a super bad idea in that regard.

The way that we did it was a little bit inverted from there. So, when we were working on the Palestinian issue, which we spent a lot of time on, and up until October 7th, the Biden administration really did not burn a lot of calories on it. They basically said, this is a lost effort, we shouldn’t spend time on it, but we spent a lot of time developing a plan.

You go online, go Google Peace to Prosperity, you’ll find the plan that we put out in the White House, about 180 pages, very detailed. We started out, I met with the Palestinian negotiators, the Israeli negotiators, and I asked them basically a form of simple questions.

First identify, what are these people actually fighting over for 70 years? It came down to a list of 11 issues, of which there were only really three of them. One was the land barrier. I looked down and I said, well, any outcome is arbitrary, to compromise between two positions. You have the religious sites where they threw in a lot of issues like sovereignty. Does sovereignty belong to God? Does it belong to this? You have basically two sites, one under the other that both religions think is very critical to them. But I said, well, what do we really want if we get all the technical people out of the room? What we want is people to have the ability to pray freely. If you think about Israel, Jerusalem was really controlled by Jordan until the 1967 war.

1967 War

Israel took over; it was a defensive war. Israel was attacked by Jordan. They basically came in, attacked by Egypt and Jordan.

Tarek Masoud: Preemptive.

Jared Kushner: Preemptive, but Egypt was amassing all of its planes on the border. Jordan had given over its military under the control of the Iraqis at the time. So, what they did is they did a preemptive attack, they knocked out the Egyptian Air Force. They sent message to the Jordanians saying, please do not attack us. The Jordanians started mortaring in.

They basically then went over; they took over Jerusalem. They were surprised they got so far, and they kept going and were able to go all the way to the sea. So, that was the history of where that was. But before then, no Jews were allowed to pray in Jerusalem.

Then you basically had a situation where a lot of the Jewish cemeteries, a lot of the religious sites were used as places to store animals. They were really desecrated in bad ways. Israel then wins the war. Israel’s a very, very poor country at the time. What did they do? The first thing they do is they pass something called the Protection of Holy Places Law, which basically took money that they really didn’t have at the time and said, we’re going to restore all of the religious sites. So, if you think about it, from 1967 until today, Israel’s been a fairly responsible steward of all these religious sites for Christians, Jews, Muslims.

Every now and then you have tussles when people try to take it. They’ve allowed King Abdullah to be the custodian of the mosque. If you think about that second issue, it’s really just about allowing people to live freely.

The third issue that I thought was critical was really just security. You think about it, I mean, we think about it with different countries, but imagine you’re the governor of New Jersey. Then there’s people in Pennsylvania who are trying to cross the border and kill your people. You have to make a deal where you’re making it less likely they’re going to be able to harm your people than more. Otherwise, you’re not going to be able to win an election and it’s not a prudent thing to do. So, those are really only the three issues that mattered.

So, what we did is we basically went and we said, asked each side, if you were the other side, what would you accept?

I found we weren’t getting anywhere so I started giving them much more detailed plan to react to.

We started going back and forth. It ended up turning into a 50-page operational plan on how to run things. By the way, you’ll find most people in politics don’t want to put details out because details you get attacked, when I got attacked even for taking my job. So I, after the third day, stopped caring about being attacked.

So, I basically said, let me start putting things out and get people to react to it. So, that was the first part, which was the political part.

The second thing we put together was an economic plan because as I was progressing down that road, I said, okay, let’s say miraculously I get people to agree on borders. Let’s say I get them to agree on a security regime. Let’s say I get them to agree that we could all pray properly and respect each other. Then what happens the next day? A lot of the region, a lot of what Israel’s been used for has been a scapegoat, I believe, from leaders in the region to basically deflect from their own shortcomings at home. So, I felt like most human beings want the ability to live a better life, and if we can create an economic plan that would basically allow people to live a better life, then maybe that would give them an ability to actually start focusing on the future, how to make their kids’ lives better, instead of focusing on, how do we solve problems in the past? So, that was really what we put together, and so that was really a framework for how we thought we could make progress. So, what Tom’s talking about is basically saying, why don’t we recognize a Palestinian state?

When we were looking at a Palestinian state, the problem we saw there was basically that they didn’t have really institutions that can govern. I mean, the last person actually who did a good job governing there is actually here. It’s Salam Fayyad. He was doing such a good job, he wasn’t corrupt. People were making more money; the services were being delivered. He did such a good job that the leadership basically saw him as a threat and figured out how to run him out of town. I don’t know if I’m speaking for you, but it did.

Tarek Masoud: I think he might also say the Israelis didn’t help them either. But anyways, we’ll go.

Jared Kushner: These are also complicated. I mean, that’s true.

Tarek Masoud: That’s one word.

Jared Kushner: But what I would say here is that for a Palestinian state when we looked at it, you say, what are the prerequisites that people need to live a better life? Number one is you need a functioning judiciary. You need a business climate. You need property rights. You need reasons for people to invest capital in order to order to give people an opportunity to grow. So, those conditions really don’t exist. So, the Palestinian leadership really has not passed any of the tests over the last 30 years in order to, I think, qualify for it.

Now, I do think the notion of a Palestinian state that doesn’t have the ability to harm Israel from a security perspective is a worthy objective, but I think you need to figure out, how do you make them earn it? At least have a viable pathway towards creating the institutions that can make it thrive and viable, because if you call it a state and then people, their lives are less good in five years from now, people will be angry and that will lead to more violence and conflict.

How Did We Get to October 7th?

Tarek Masoud: Okay, so there’s a lot of threads to pull on here. So the first thread I just want to pull on is, you offered a diagnosis for how we got to October 7th, and your diagnosis is basically the Biden administration by allowing the Iranians to amass more wealth and spend it on their proxies, that’s how you get October 7th. If President Trump had been in charge, none of that would’ve happened; the Iranians would’ve continued to be starved of resources, et cetera. I’m correct on interpreting that hypothesis?

Jared Kushner: Yeah. I’ll add one more element, which is they squandered momentum. What I would say is whether it’s in business, whether it’s in politics, momentum is one of the most valuable things to try to seek. It’s funny, I was talking, I wrote about it in my book; actually, with Bibi, that I was with him after he lost an election, not a lost election, he was trying to form a coalition. Somebody put a knife in his back and he basically lost it.

I was with him the next day. We thought we were going to announce something and move forward, and he was pretty despondent. We met the next day, and he would basically, I figured, let me ask him questions about his history, his story. I mean, he’s a historic figure that’s been through so many different iterations, and he told me, “When I was a politician, I have bad patches. I would always try to get little wins because little wins lead to bigger wins and then bigger wins and momentum is a very hard thing to get.”

We left the region with momentum. Again, the last piece, so we got Bahrain to do the deal with Israel. Saudi was basically watching this all very closely. We got Saudi to allow us to put flights over Saudi Arabia between Israel and UAE.

Then in addition to that, they’ve said, we need you to solve the issue with us in Qatar. So, we went through, we got that negotiation done, which was very, very intense.

So, I finished that on January 5th and then flew back to the US, thinking I would have a very quiet last couple of weeks in office. That turned out to be the case. So, basically, everything was good. What they could have done was then said, let’s sit with Saudi. Let’s go finish the job. Let’s finish the momentum. So, they basically changed policy, and I think that led to a reversion of momentum. They waited two years to get started, and then get a stronger Iran, less trust, and I think that also contributed to it as well.

Was October 7th the Result of Neglect of the Palestinian Issue under Trump?

Tarek Masoud: Okay, so what would you say to the alternative hypothesis that says, actually, the reason we got October 7th is because the strategy that you had for peacemaking, which whose creativity I’m not going to question, it was quite creative, but by essentially neglecting the core of the issue, the Palestinians’ desire to determine their own fate, that you just created the circumstances where the rejectionists would have the upper hand. That this is basically not the result of Iran or whatever, it’s a result of the fact that the Trump administration spent four years completely ignoring, isolating, bypassing the Palestinians, handing them defeat after defeat after defeat. Then what do you expect? You’re surprised when they act out?

Jared Kushner: Right. So, what I would say to that is that whoever would say that, that we didn’t address the root cause of the situation, I don’t think truly understood what the root cause of the situation actually is. This is what was actually so intriguing to me and what made me very insecure about my job in the beginning was that I came into this with, like I said, no foreign policy experience.

Everyone who was criticizing was probably right, but I think my father-in-law, who’s the President, basically said, it can’t get any worse. He can’t do any worse than the last people who worked on it for 10 or 15 years and all failed, and then basically went and wrote books about how they didn’t fail.

It’s just that the problem was too hard, and then somehow, they move on and they are considered the experts on the situation, having had zero accomplishments on this file.

So, that’s the underlying function of what you’re talking about. I saw this very simple, and actually when I went to the United States, the UN Security Council, because always trying to condemn Israel on everything, it was very anti-Semitic, I think the way that they conduct their business there.

I basically made a PowerPoint presentation. I don’t know if anyone’s ever made them a PowerPoint presentation, but coming from the business world, I said, maybe I can try to explain to these people why this is a rational thing in a very realistic place. I actually put this slide in my book where I basically made a slide from Oslo Accords up until that day, where I showed two lines going this way. Then I had a dove for every time there was a peace talk that failed.

Then I had a tank for every time there was a war. The two lines represented the following things: One was the settlements; so, basically the land that Israel was taking. Then the other one represented money going to the Palestinians. So, what happened was, is every time a peace talk failed or a war occurred, the same two things occurred. The Palestinians got more money and the Israelis took more land. So, both sides essentially got what they wanted.

So, neither I thought had a really motivation to make the deal based on their own politics and their own interests. Then the second thing was, is I looked at it and I said, these issues actually are not that hard to solve. Which again, a lot of people laughed at me for saying that, but I basically said, we have to figure out how to just push this forward.

So, when I looked at the Palestinian leadership, I basically said it’s like… And there’s a lot of other situations of refugee groups; they just haven’t been able to internationalize their situation. The Palestinians were getting $3 or $4 billion a year in international aid. We had a meeting in Washington with Bibi Netanyahu. They have a $500 billion GDP economy; they’re a nuclear power, military superpower, a technology superpower.

He would fly in on an El-Al commercial plane with his team. We’d meet with the head of a refugee group, Mohammed Abbas, and he would fly into Washington on a $60 million Boeing business jet. I mean, the whole thing was strange. I went and I met with him one night.

We’re talking about different issues and he wants a cigarette. He puts a cigarette in his mouth. So, someone comes in and they light the cigarette for him. I’m saying to myself, is this guy run a refugee group or is he a king? So, the whole situation, I thought, was designed for them not to solve it.

Again, a lot of people were getting rich there, a lot of interests were being fed, and not a lot of people were doing it.

So, what we basically said is, we’re going to actually address the issue. We’re not going to deal with the systems of the issue, we’re going to try to address the issue. I think that was what we actually tried to do.

Why is Kushner’s Assessment of Mahmoud Abbas so Different from Trump’s?

Tarek Masoud: Okay, so there’s a lot to pull on here too, with respect to Mohammed Abbas. So, I’m going to just stipulate at the outset, some of my favorite bits of this book are your descriptions of conversations with Mohammed Abbas. I’m not on his list of fans, but let me quote somebody who is on his list of fans, your father-in-Law. So, he told Barak Ravid, “Abbas: I thought he was terrific. He was almost like a father. Couldn’t have been nicer. I thought he wanted to make a deal more than Netanyahu.”

What was your father-in-law getting wrong?

Jared Kushner: Well, I think he was saying relative.

Tarek Masoud: Okay, relative.

Jared Kushner: Relative, so.

Tarek Masoud: Okay, relative to Netanyahu though.

Jared Kushner: His view on Bibi was that Bibi was always working something. I think that he did not have faith that Bibi would come through, but I also think he was in his mind trying to challenge Bibi to say, you’re not going to come through, you’re not going to come through, to make Bibi prove to him that he was going to come through. That was the way we were setting the table. So, what we did is we did things that we wanted to do anyway.

President Trump campaigned that he was going to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. His view was, is Israel’s a sovereign nation, America’s a sovereign nation, they have the right to determine their capital and we have the right to recognize their capital. Move the embassy to Jerusalem, Golan Heights. I mean, who are you taking it from? Syria barely existed at the time and Israel had occupied it for a long time.

Recognizing Golan wasn’t that big of a deal. So, we did all these things that built a lot of trust for us with the Israeli public.

What happened was, is because of that, the Israeli public trusted President Trump, he got out of the JCPOA, he was strong on Iran. He felt that he had the ability to say this is a fair deal, and push Bibi to that place. A boss would come and in the meetings he would say, “We’re going to do a deal with you. We’re going to do a special deal. I’m going to do things for you like I’ve never done for anybody else. We’re going to make a deal.

We really want to do it.”

I’d be like, oh, that’s amazing. So, that was my first meeting. I walked away and be like, that was incredible. This guy is great.

Then I went from my second meeting, I go all the way to Ramallah. I go in, it’s, I’m thinking to myself, how is a Jewish kid from New Jersey here in Ramallah?

I got all the security guards. Then I meet with him again and I say, “Okay, well, I’m ready to talk borders. What are we going to do? What’s your proposal? I want you to tell me what would you do that you think the Israelis would accept?”

“Jared, we’re going to make a deal. We’re going to make the best deal. I’m going to make a special deal for you.”

I’m saying myself, I really want to get into the details here.

My father-in-Law’s not a very patient person. What I found was it was like a broken record. What I realized, if you go back, what I did at some point, I read actually Jimmy Carter’s book, which was interesting. I really wanted to get the full-

Tarek Masoud: Peace, not Apartheid [Palestine: Peace not Apartheid], or something like that.

Jared Kushner: Peace, not Apartheid. Yeah, I tried to get everywhere from Dory Gold to Jimmy Carter. I really tried to get the spectrum of perspectives. In the back of it, he had in the annex, the Camp David Peace Agreement.

I was reading through the agreement. I was like, I actually should go read all the different drafts of agreements and let me go read some peace agreements to see what they actually are.

Everyone’s there trying to negotiate, but I said, let me go read some.

So, then as I pulled up all of the different agreements that have been done, I saw the Arab Peace Initiative, and that’s what Abbas said, “I want to align with the Arab Peace Initiative.” So, I pulled up the Arab Peace Initiative and it was 10 lines and it had no detail, and it was a concept, and it was generated in a different place.

One of the tenets of it was, we want a capital in East Jerusalem. So, I had a guy on my team who was awesome, a guy Scott Lith, he was a military guy, and I said, he worked for John Kerry. His whole life has been working on this issue, but he was from the State Department, which was a much more, a different perspective than say a former business guy who’s more of a pragmatist would have.

East Jerusalem as Palestinian Capital

I asked him, I said, “Well, where does the Palestinian claim for East Jerusalem come from?”

Tarek Masoud: You mean East Jerusalem as a capital?

Jared Kushner: As a capital, yes.

Tarek Masoud: Not as belonging to them.

Jared Kushner: Sorry, as a capital. I said, “Where does that come from?” He says, “I actually don’t know.” I said, “Okay, well, go research and get back to me.”

Normally he’d be back in my office in two hours. He didn’t come back for two days. He basically came back and he says, “You know what, Jared? This is very interesting.” He said, “Before the Palestinians said that they were in charge of the West Bank,” which basically was the declaration, which I think was in the late ’80s?

Tarek Masoud: Yeah, late ’88.

Jared Kushner: Late ’80s, right?

Tarek Masoud: ’88, I think.

Jared Kushner: So, until then, the Palestinian lands were basically territory of Jordan. Jordan, the Palestinians were basically fighting with the Jordanians causing problems there, and the Jordanians basically said, we’ve had enough of these people, let’s get them out of here. They basically exiled Yasser Arafat to Lebanon, where he went there, caused a lot of trouble, they exiled him to Tunisia.

So, during that time when the Palestinians were in the West Bank, their capital was Amman.

So, he’s saying, actually, it was just through this declaration of the Palestinians when they said, this is how we’re forming our charter. This is what our rights are. They just said, and we’re taking East Jerusalem as our capital. So, it was just one of these things that came down.

Tarek Masoud: Declaring East Jerusalem as their capital.

Jared Kushner: Declare, yeah.

Tarek Masoud: In other words, East Jerusalem was always going to be part of what a Palestinian state was because they had never ceded it.

Jared Kushner: Yeah, part, but what I would say about that, and this is also another notion, is that, again, because a lot of, you’ll hear people throw around a lot of words like they’ll throw apartheid or East Jerusalem [inaudible]. My view is, these words are always up here.

Then again, somebody who wasn’t part of the club of foreign policy experts, I said, well, explain this to me. East Jerusalem, the boundaries of East Jerusalem have changed eight times over the course of history as well.

So, when they were saying that, I said, oh, well, there’s new, maybe we could expand East Jerusalem, give them a different part of it. So, it’s one of these things that if you’re pragmatic about it, there’s ways to solve a lot of these different issues, if you want to do it.

What we found with Abbas was that there wasn’t a great desire to engage because he was protecting the status quo, which was leading to lots of inflows of money.

Challenging Kushner’s Assessment of Abbas

Tarek Masoud: Okay, so I do not want to be the guy defending Abbas to just make this interesting. Let me-

Jared Kushner: I like him, personally.

Tarek Masoud: Let me offer you the alternative argument. First of all, there’s a really amazing negotiator who said you always let the other guy go first. Who was that? Oh, it was Jared Kushner, it’s in this book. Okay. So, you go to Abbas and you say, Hey, draw a map for me. A smart negotiator is going to say, Hey, the map is resolution 242, the entire West Bank. If you’ve got an offer you want to make, go ahead, but I’m certainly not going to negotiate against myself. Why didn’t you recognize that that’s what he was doing?

Jared Kushner: Yeah, so that’s what I saw was this kid’s situation. So, what I did was, since both parties were doing that, I just went and started drawing my own map. I basically said, okay, I don’t really care what happened before, because if you think about the Middle East, a lot of it’s just arbitrary lines drawn by foreigners anyway. You go back to Sykes-Picot, and you could argue that there’s a lot of lines.

Again, as I started unraveling this history, I was realizing that a lot of this was not as logical or as sacrosanct as everyone thought it was. So, what I basically said is I said, okay, let me come up with a 2017 version.

What I’m basically going to do is look at, say, if you go back to 2006, Israel unilaterally withdrew all of their settlers from Gaza, and it was a political disaster. What did they get for it? They left all these greenhouses; they left all this industry. It was all destroyed. They ended up with a group, with a terrorist group took over, and then since then they’ve

been firing rockets into Israel and Israel’s been less safe because of their withdrawal, and October 7th proved that.

But this was even before that. I said, there is no way Israel’s uprooting any of these settlers. So, I said, let me just say if I want to give the Palestinians a state, let me figure out how can I draw a line and just take all the places where they’re settlers and just make a new line here, and then figure out, how do you swap land here and there?

Then make whatever’s not continuous, continuous today. You got tunnels, you got bridges, all these different things. How do you make it connectable so that it could be a functioning state? Then go from there. So, I started drawing a line, and then I figured I’d let each party react to it one way or the other.

We ended up putting it out. Again, I fought a lot with Bibi and his team, through showing him the map. You can’t have this; you can’t have that.

I said, okay, let’s move the line here and there, but that was how I started. I was never able to get the Palestinians to engage off of that map to say, we want this, but.

Did Kushner make Abbas an Offer He could not Accept?

Tarek Masoud: Yeah, so this is interesting. I mean, obviously you’re a great negotiator. I’m a fat professor who’s never even negotiated his salary properly, but-

Jared Kushner: That’s usually what the people who are doing well say, by the way.

Tarek Masoud: But the way you present, I did think it was, you really deserve a lot of credit for getting Benjamin Netanyahu to put down on paper the borders of a Palestinian state that he would accept. Okay, you’re the first person to really get them to do that.

Jared Kushner: Not just him; we got the opposition during a heated election to agree to them as well.

Tarek Masoud: To agree to it, to agree to it.

Jared Kushner: A massive step forward.

Tarek Masoud: Yeah, massive step forward. One of the great things that you say in this book, by the way, which I actually think is exculpatory of the Palestinians, is you say, everybody says, Camp David 2000, the Palestinians walked away from a really detailed agreement. There wasn’t a detailed agreement. So, that’s actually a little bit exculpatory for the Palestinians, but in any case, you finally get Benjamin Netanyahu to put down on paper, what he will accept.

Jared Kushner: Just from my research, I was not able to find any text of a deal that was anywhere near close to a negotiation. I also thought the power dynamics were different, where is what I was told is that Arafat was basically not being supported by the Arabs. The Arabs wanted to keep this thing alive and they didn’t want him to make a deal.

Whereas today, when we got in, I recognized the different dynamic, where the Arabs I felt wanted him to finish this, which gave me a lot more ability to lean into things.

Tarek Masoud: Yeah, that’s interesting, but the point is, so you’ve got now Benjamin Netanyahu’s drawn the map. Why do you not take this to Abbas or why do you not announce this as the American plan to which the Israelis have signed on? You are the American; you’ve got this position as the broker between these two parties. Why didn’t you go back to Abbas and say, okay, here’s what the Israeli position? Then let Abbas say, okay, no, I don’t like this border, I don’t like that. Then why didn’t you do it that way?

Why did you present it in such a way where it looked like what you were trying to do was to give him an offer he couldn’t accept, so that you could then say to the other Arabs, ah, this guy’s a rejectionist, I did my best. Can we now conclude some peace deals directly between you and the Israelis and leave these Palestinians on the side?

Jared Kushner: I’ll try to do this answer as short as possible, but it’s going to be a little one. So, number one, what I tried to do is set up the situation. So, when we moved the embassy to Jerusalem, Abbas and his team said, we’re not talking to you guys anymore. After a couple months, they came back. We kept the security cooperation going, but he broke ties with us diplomatically. I remember at the time, Rex Tillerson, who was the Secretary of State, said, “We’ve got to go do something. Let’s give East Jerusalem. Let’s do this because these guys are going to run away and we’re not going to hear from them again for another decade.”

I said, “Rex, we’re not doing it.” He said, “Why?” I said, “They’ve trained American negotiators over time to say, jump, and we say, how high?”

When have American negotiators bowed to Palestinian demands?

Tarek Masoud: I read that in the book, and I thought that was an extraordinary. Give me an example of where we said to the Palestinians, you told us jump and we did it.

Jared Kushner: Everything with me was a threat. “We’re going to withdraw from the negotiation.” I said, “Who cares? We give you guys $700 million a year. I don’t care.” My view is, if you’re going to come and do it, great. If not, we’re going to stop funding you guys. But that’s how we’re going to set the dynamic. So, then the second thing I did was I said, “We’re not going to allow you to control whether we can negotiate this or not.” So, because they withdrew, I said, “Okay, I could stop.” Now, the good news is I had other files to work on.

I wasn’t a sole person, but the reason why the U.S were trained to chase them is usually it was an envoy whose sole job it was to deal with the Israelis and the Palestinians. And the Palestinians said, “We’re not negotiating.” He had nothing to do. For me, I said, “Okay, I’ll work on other things. That’s okay. I have other jobs here.”

And so, what we basically did was we went and we started pushing forward with the plan.

And my thinking was, as I was speaking to the Arabs, they said, “Get an honest plan on paper from Israel and we will try to push the Palestinians to take it.”

Because they basically said, we want this thing resolved. So, they said, if you can put a credible offer, and they did not believe that we can get Bibi or United Israel to put forward a credible plan, I said, “Good, let’s do it.” Again, I was always willing to chase the crazy things and I kind of liked it.

And again, I felt like this was very important. So going after and trying to settle things I thought was critical.

So, we worked hard with Israel. We kept negotiating with them to get them more and more. I didn’t take them all the way to where I thought we could have gone. Security wise, I was in full agreement with everything we put in our plan. Again, I really was very sympathetic to Israel.

You can’t make a peace deal and then be less safe the next day. You do a deal so that you’re more safe. So that was number one.

The borders, I felt like we should just be super pragmatic about it. And there was a couple of things in there that I knew we could swap around. So, I left some meat on the bone for Abbas. I’m going to get to the answer to your question. So, I kind of left some meat on the bone.

Then when we announced the plan; so first of all, we surprised everyone by getting Israel to put out a very detailed plan.

We had a unified Israeli government supporting it. We got very positive statements from the Arab country saying, we encourage both sides to negotiate on the base of this plan, which diplomatically, was actually a very big step forward in the diplomatic world.

Then what I did is I had the CIA deliver to Abbas a copy of the plan with a note from us right beforehand, basically saying, this is the plan we’re putting out. We have built a lot of goodwill with Israel. We are willing to use that goodwill to try to make a fair deal that we think can resolve this.

Tarek Masoud: That’s the question I’m asking. So, why that framing? Why didn’t you say, here’s what the Israelis are offering. Give me your counteroffer. Why didn’t you do that?

Jared Kushner: That’s essentially what the letter said, right? The letter basically from the president said, we’re happy to chat. And basically we said, look, we’re happy to chat. We’re moving forward with this. We had to set the dynamic where the train was moving forward with or without him, and this is what I do believe, too. They were very isolated. They were basically running out of cash. Iran was running out of cash, and we had the only thing on the table. The Abraham Accords were now starting to collapse the pocket around them.

And so basically what we were doing is we were trying to eliminate all of his escape paths and build him a golden bridge. And then basically, at some point we figured he’d go over the bridge.

Did Kushner Prove Hamas and Others Right?

Tarek Masoud: I feel like the natural response to that is very clever deal making. I certainly would not want to be on the opposite side of a real estate transaction with you. But what you weren’t recognizing is that Abbas has people to his right, he’s got Hamas that he’s got to contend with, and you were just making it absolutely impossible for him to make a deal with you. And all you were doing here is just proving the rejectionist point and making the average Palestinian think, yeah, absolutely. America has no intention of actually being an honest broker or getting us a good deal.

Look what they’re doing to Abbas, who is their ally. So then, maybe the only path is the path of this violent resistance.

Jared Kushner: So, I hope you’re saying that in the context of being provocative or devil’s advocate-

Tarek Masoud: Yes, yes.

Jared Kushner: Because my sense is that’s the total conventional way of thinking about this. And again, I’m saying this openly. I was criticized by all of the conventional players on this because I did not approach this-

Tarek Masoud: But October 7th happened.

Jared Kushner: Right. But let me go back to that point. So, the point there is that the other version of what was said is that if you move the MC to Jerusalem, the Middle East is going to have a war. That was the US intelligence assessment. That was what Abbas said. That’s what every leader in the region said. If you get out of the JCPOA, the world’s going to end. If you move the embassy, the world’s going to end.

Well, every time we did one of those things, we worked to mitigate the risk. And what happened the next day? The sun rose in the morning and it set in the evening, and nothing happened. We had little things, we managed them. It was no big deal. So, our thinking was is that if you’re going to say that Abbas can’t engage with us and try to make a compromise because Hamas is to his other side, we thought the best way to empower him over Hamas was to make him the guy who delivered investment, upside, compromise, better life for the people. And that’s how we read the situation back in 2019, 2020.

And I still believe at that moment our assessment was correct.

Why did Kushner not Try to Build Capital with the Palestinians?

Tarek Masoud: Yeah. I want to move on to other issues, but I just want to, when I look at the way you negotiated with Bibi, okay, so you mentioned, for example, to move the embassy to Jerusalem, for example. Every time you made one of these decisions and President Trump would say, Hey, what am I getting for this? You want me to move the embassy to Jerusalem, what’s Bibi going to give me? Oh, you want me to recognize Israeli sovereignty over the Golan? I’ve already done enough for Bibi. Why am I going to do this? And every time you would say to the president, Hey, hey, hey, we’re building capital with the Israelis. We’re building capital with Bibi. Why weren’t you trying to build capital with the Palestinians?

Jared Kushner: First of all, Israel was the much stronger party. And so, at the end of the day, we felt like getting the right pragmatic compromises out of them would take the capital and we would have to convince them that the compromises we were going to ask them to take, we genuinely believed were in their interests.

Keep in mind, all of the things we did for Bibi were things that we thought were the right things to do. So, he was a political beneficiary of them. He would tout them for his domestic and international popularity. But the reality is, we were doing things that we thought were the right things to do.

Why didn’t Kushner get Netanyahu to Freeze Settlements?

Tarek Masoud: Why didn’t you at least get him to freeze settlements? Say like, Hey, I’m going to give you Jerusalem. I’m going to recognize the Golan.

Jared Kushner: If you notice with us, the settlements were basically contained to areas. He did pro forma stuff, but nothing that was that radical. He didn’t go too crazy with us in the settlements.

Tarek Masoud: Okay.

Jared Kushner: But again, our strategy was basically have the tough conversations quietly, figure out how to mitigate. Again, you could have disagreement, but let’s focus on the big things. I remember I got a call from David Friedman, who’s our ambassador to Israel and said, “Oh, Jared, we have to deal with this. Two Israelis were [inaudible].” I said, “David, stop chasing rabbits.” I said, “Our job is not to solve every single domestic Israeli issue. Our job is to focus on the elephants. The elephants are slower, they’re bigger. Let’s focus on the root cause of this. If we solve the root causes of the disease, the symptoms all go away. If you spend all of your time chasing the symptoms, you’re going to wear yourself out, you’re not going to get anywhere.” And that’s what a lot of people did before us. So, we stayed very laser-focused on how do we make both sides uncomfortable to try and create an outcome.

And I’ll just say this too, Middle East peace is like a butt of jokes for many years. We actually did get some peace agreements done, which is pretty incredible. But you’re basically saying, Jared, go work on probably one of the most impossible, complex, emotionally charged problem sets in the history of the world. And so my view was, it wasn’t like you could look at it on one of your homework sets.

Okay, this is the right answer, the wrong answer. You have a million different wrong answers and maybe one or two potential answers that could work out well. And so like I said, we inherited the hand we got and we just played the cards as hard as we could. And I do think by the time we left, we left it in a very, very strong place. And we had more time, again, I don’t want to sound like one of these guys who leaves government saying this, but I did have a lot of track, my track record of success in the Middle East I do think is second to none over the last many years.

And so I do firmly believe that we put the situation in a paradigm where it was much closer to being solved than it had ever been before.

Why Does Kushner not See Netanyahu as an Obstacle to Peace?

Tarek Masoud: I’m going to just do one last question on Bibi because I started this by saying you and your father-in-law disagree about Abbas. You also disagree about Bibi. And I guess what I’m trying to understand, because I read your book, I don’t know why you still have a soft spot for Bibi. Like this is a guy who, Trump says, I don’t think he ever wanted to make peace.

You tell a story where Netanyahu acts incredibly dishonorably, where when you’re rolling out the peace plan, he gets up and just starts thanking the United States for agreeing to Israeli annexation of these bits of the West Bank that Israel, in your plan, would only get after the deal is agreed to by the other side.

And you even say, when you first started talking to Netanyahu about a deal, he says, no, thanks.

And you even note, he says to you, look, I’ve survived as Prime Minister for 11 years by opposing a Palestinian state. So, this, to me, he’s a guy who just purely, in your book, seems pretty sneaky, kind of like an obstructionist, a rejectionist. And yet, you talk about him in the book, towards the end you say he could be a powerful catalyst for change. And I’m thinking to myself, yeah, it seems to me he was more an obstacle to the kind of change that you wanted and the U.S wanted, which was to see a solution to the Palestinian issue. So, what am I and your father-in-law getting wrong about this guy?

Jared Kushner: So first of all, I think that there definitely is brilliance to him, and I think he’s definitely committed himself to Israel for a very long time.

Some would argue maybe now too long, but I think he’s done a lot of good in his time. And my general view is, I was able to find ways to work things through with him. He didn’t always make my life easy, but that wasn’t his job.

My job wasn’t to make his life easy either. So again, I understood his complications, I understood his flaws, and I understood his brilliance, and I was able, and I just found it, and again, maybe I’m more malleable. I’m able to work with complicated people very well, that’s maybe one of the things throughout all my different careers I’ve been good at. But I found that I was able to get the best out of him in order to accomplish the things that I thought were in the best interests of America and the region.

Tarek Masoud: So, in other words, just bottom line on this, you are not one of the people who sees Benjamin Netanyahu as an obstacle to peace?

Jared Kushner: I think that anyone who is a leader in the region can be both part of the problem and part of the solution. And I think that the job of those involved is to try to pull the best out of everyone to create the best possible outcome possible.

Tarek Masoud: I definitely…

Jared Kushner: I know I’m being a little evasive with that, but I think it really can depend on the day, and I think it depends on how you work with him to get the best out of him.

Tarek Masoud: No, I love that.

Jared Kushner: It’s in there. It’s in there. That is what I’m saying.

Tarek Masoud: I love that. I love that. It’s clear from the book you did that with Netanyahu, but you gave up on Abbas really quickly.

Jared Kushner: I didn’t give up. I was just taking a posture of, we’re not going to chase you. But I think, for him, I set a very delicious table where if he would’ve come and engaged, I had a couple goodies in my pocket that I could have done, and I think I set the table for him to make a deal, have some big victories in negotiation, have $50 billion of investment, create a million new jobs, double the GDP, reduce the poverty rate, create a real country. You know what I mean? So, I think I set him up to be a hero.

Look, there’s one book I read about him, which actually I had a different assessment of him than the CIA. And I actually bought this book and gave it to the CIA after I read it, which was called The Last Palestinian, which was really incredible. And throughout his life, again, this is my assessment as just somebody who ended up in this job, was that throughout his life, he actually was for peace. He was for nonviolence. He hung around a lot of bad characters and was always on that side. But I do think that after they lost Gaza to Hamas in 2006, you basically had two non-states with two non-governments. And I think after that, he just went inward and his whole focus moved to survival and staying in power and keeping the kleptocracy running. I think after that, it was more about how do I set this up to just survive. And he became afraid of making peace and taking the risks necessary. That was kind of my assessment, which made him a little bit of a harder character to deal with.

Why was Recognizing Israel’s Annexation of Golan the “Right Thing to Do?”

Tarek Masoud: We could probably talk about him for much longer, but we shouldn’t. You saw the Vanity Fair story that talks about you as a potential future Secretary of State. I don’t know if people saw the New York Sun story from January that proposed your name for president of Harvard. But so what I want to do is I kind of want to, I want to understand how you think about international relations. And the Golan story gives us a nice entry point into that.

So, March, 2019, you encouraged President Trump to recognize Israel’s annexation of the Golan Heights. And basically you say, acknowledging the reality that the Golan Heights belonged to Israel was the right thing to do. And I remember I read that thing and I thought, wow, Jared Kushner is talking about the right thing to do. I’m a realist in international relations. I would’ve guessed that you were as well. It’s like there’s no right or wrong. It’s like interests. So, what was the moral principle that was being satisfied by recognizing Israel’s annexation of the Golan?

Jared Kushner: Sure. So even with all these jobs, my number one job that I’m focused on right now is being dad to my kids. That’s something after four years of very intense time in government. That’s the most important job I have now.

Tarek Masoud: That’s your way of saying you don’t want to be Secretary of State?

Jared Kushner: That’s my job. That’s my way of saying I’m really liking the job I have right now. It’s really important.

So, what I would say is that the way that I kind of approach foreign policy, and again, this came from not really having any experience in foreign policy, was basically saying every problem set I got almost, I think my disadvantage was that I didn’t have any context, and my advantage was that I didn’t have any context. So, I would always try to take a first principles result-oriented approach with the goal of being, how do you maximize human potential? And in order to maximize human potential, you need to figure out how you can reduce conflict, most of the time. And I always looked at everything and I say through that lens, what are the interests of different parties?

One thing I was also very good at, I think because I didn’t come in lecturing people. There’s a story I tell in the book where I went to meet with Mohammed bin Zayed, who’s now the president of the United Arab Emirates and the ruler. And I spent the first two hours basically asking him different forms of a question, which is, “The US has so much power, again, we are a massive global superpower. If you were me, what would you do?”

And it took him about an hour to basically understand the question I was doing because he was so not programmed to actually meet with somebody from the US who wanted his opinion.

And after an amazing conversation, because he’s a very, very wise and brilliant person, he basically said to me, “Jared, I think you’re going to make peace here in the region.”

And I said to him, I said, “Well, why do you say that?” He says, “Well, the US usually sends one of three kinds of people to see us. The first are somebody who comes and they fall asleep in meetings.” He says, “The second type of person they send is somebody who comes and they read me notes or a message and has no authority or power to interact and have a dialogue.” He said, “The third person they send are people with real authority, but they only really send them to come and try to convince me to do things that are not in my interests.” He says, “You’re the first person from the US at a senior level that’s ever come here and actually asked questions and listened.”

And I said to him, “Well, that’s because I really don’t know how to do this, and this is a really hard problem.” And so I said, “I appreciate all of the wisdom you can give me.”

So, it’s kind of a long way of saying that every problem I kind of looked at fresh. I was able to build trust with people, build real personal relationships. I always answered the phone. People had issues. I always believed successful people answer their phone and so I was always available. I didn’t always tell them, yes.

And I wasn’t keeping a score saying, I’m going to do this for you, but you have to do this for me. My general view was, I’m going to do all the things you need and you’re going to do all the things I need, and hopefully at the end of this relationship, we both feel like we’re way ahead. And so I was able to build a lot of trust.

I was able to kind of see things from another side’s perspective. I worked very hard to understand both side’s interests and say, where can we find common interests? And then the areas where we disagreed, instead of condemning people publicly, you’ll notice I didn’t do a lot of public talking. I didn’t think it was that helpful. I’m not very big on being negative towards people or being critical.

And so what I basically did was we would find ways when we disagreed to disagree respectfully and quietly, and then find ways to move forward.

Tarek Masoud: So, sorry, recognizing Golan’s annexation was the right thing to do because…

Jared Kushner: Well, it’s just obvious. I mean, number one, Israel had had it now for how many years? I guess they got in the ’73 War.

Tarek Masoud: Yes.

Jared Kushner: I believe so.

Tarek Masoud: [inaudible] I don’t remember it.

Jared Kushner: They had it for a long time. The ’67 War.

Tarek Masoud: Yeah.

Jared Kushner: The ’67 War. So, they basically had it since the ’67 War. Clearly, strategically, it was a big military, important. They had it, they weren’t giving … And then they’re saying, okay, who does it belong to? Syria. Syria, at the time, barely existed.

So, it was a big thing where it said, A, they’re never giving it up. B, Syria doesn’t exist. Let’s just recognize it. It moves things forward. And my view is the more of these what I would call stupid conflicts that we allowed to exist, the more it would be there. What I would say too is the Middle East has a lot of natural negative inertia to it. It’s been created over so many years. Maybe it’s the mixture of so many customs and traditions.

But I would say in 2017, what was new to the situation was really two things. One was President Trump and myself as a proxy and then MBS. And so with those two dynamics, we were able to disrupt the inertia and then really change the paradigm of what was there.

Tarek Masoud: You have this other line in the book where you say, “Recognizing Israel’s annexation of the Golan was a powerful opportunity for America to stand for the truth.” But that felt like very moral language. For example, I don’t imagine you would say, oh, let’s also stand for the truth of the fact that the One China policy doesn’t make any sense, and there actually should be an independent country called Taiwan. You wouldn’t stand for that truth.

Jared Kushner: Well, I think that that was a truth that didn’t conflict with one of our strategic interests.

Tarek Masoud: Okay, fair enough. Okay, fair enough, fair enough.

Jared Kushner: But I’ll tell you where we did do that. We did that in the Western Sahara. We recognized the Western Sahara as being part of Morocco because, again, we thought that was in our interests and it was true. And so it was just like one of these, and again, that has not been undone, too.

One thing I’m proud of with a lot of the work I did in government, people talk about how it was a divided time. Abraham Accords have been bipartisan praised, and now the Biden administration has followed our policy.

After two years, they’ve reversed course; they’re embracing Saudi Arabia. All the things we are doing, they’re now trying to do, which is I think a great affirmation of the policy. And it’s good. The prison reform, we did; 87 votes in the Senate. You look at the USMCA trade deal, [inaudible]. So, my view is if you pursue the things in the right way and you build consensus, you actually can move forward big things. So, Western Sahara, we did the right thing and we were able to then work hard to convince everyone to come on board.

Kushner’s Relationship with MBS

Tarek Masoud: We’re coming to the time where I have to take questions from the students, otherwise I will not make it out of here alive. But I wanted to ask you, just one last issue I wanted to describe. You talk about yourself as trying to move big things forward. Another person trying to move big things forward, who is a friend of yours is Mohammed bin Salman, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, and I think you and I are in agreement that he’s probably one of the most consequential people in the world right now in terms of the magnitude of what he’s trying to do and in terms of how important it is for the world that he succeed.

But I think when I look at him and what he’s trying to do, there are some things that just kind of give me pause. And I’m asking you as a friend of his to help me understand why these things shouldn’t give me pause. So, I’m totally going to overlook the Jamal Khashoggi thing or the detention of the Lebanese Prime Minister or the Ritz-Carlton. Just looking at some of the developmental plans like The Line, which is this a hundred-mile-long linear city. And you are a real estate guy, does The Line make sense to you?

I look at this and I think this seems to me like a guy who’s got a lot of testosterone, and nobody who wants to tell him, no. What am I getting wrong?

Jared Kushner: Got it. So, he definitely has very high RPMs from the first time I met him. So, I’ll give a little bit of context. So, Mohammed bin Salman is now the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia.

When we were in the campaign in 2016, Trump was very tough on Saudi.

And then, I write in my book, if you want to go through and read, I was very, very rough with them when they came in trying to speak. And I said, look, we want nothing to do with you guys. You guys fund terrorism, you treat women terribly. You’re not ascribing to Western values. You got to pay for your own defense. You got to recognize Israel. We’re done. This is going to be a very rough, rough go. And they did not get along with Obama because Obama basically went to Persia and did the deal with Iran, which made all of our allies feel very alienated. So, they basically came back and said, no, no, no, we really, really value the U.S relationship. It’s been our strongest relationship forever. And we have this young Deputy Crown Prince who really wants to go forward and make a difference here, and he wants to change things.

And so then basically, we had a big debate internally, and he sent me a whole proposal through his guys, [inaudible] and Dr. Mosaad Al-Aiban. And they basically brought a proposal that basically said, we’re going to do all these modernizations. We’re going to get rid of the custodianship laws. We’re going to start allowing women to drive. And by the way, we’re not doing this for you. We’re doing this because we want to do it. We’re going to be eliminating the role of the religious police. At the time we had the Pulse nightclub shooting, we had the San Bernardino shooting. The biggest problem in 2016, a big issue in the campaign was really radicalization. ISIS had a caliphate the size of Ohio.

And the whole talking point was we needed to defeat the territorial caliphate of ISIS, and then we need to win the long-term battle against extremism. There was a real fear that these extremists were basically using online mechanisms to radicalize people all over the world. We needed to stop the flow of funds to terrorists. So, they came with a proposal saying, Saudi Arabia, the custodian of the two holy mosques is going to lean into this and help you create a whole center where we’re going to now single-handedly lead the fight with you, to fight online extremism and radicalization. And by the way, they never called it modernizing Islam. He would always say, I want to restore Islam. He says, these people who were the terrorists, the ISIS, they don’t represent Islam. They are basically doing awful things in the name of Islam, and they are giving us Muslims a bad name, and we are just as aligned with you.

Again, we don’t think Trump is against Muslims. We think he’s against Islamic extremists who pervert our religion. So, they came with this whole proposal; look, we’re going to do hundreds of billions of dollars of investment in the US. We’re going to start paying for a lot more of our defense.

And it was like a dream come true from everything I thought Trump would like. They bring the proposal. Again, me knowing absolutely nothing about Saudi Arabia, nothing about foreign policy. I bring it to the national security team and I say, well, this is a proposal we got from Saudi. Is this interesting? This is, Jared. One of these things would be revolutionary. I say, well, they’re saying they’re going to do all of it if we kind of lean into the relationship.

So, then we go into the situation room to kind of assess what do we do with this? And I’m sitting with Secretary of Defense Mattis, Tillerson, John Kelly, Homeland Security. And, and Tillerson’s saying, “I’ve dealt with the Saudis all my life. I ran ExxonMobil. I know the Saudis. They never keep their word and they never come through. Jared, it’s a nice thing, but you’re a young, naive guy and it’s not going to go anywhere.”

I said, “Look, they’re putting it all in writing.” I said, “Why should we predetermine them to a future where nothing happens? If they’re saying they want to make these changes, let’s give them a little bit of rope.” So, we take it to the president and he’s doing a call with King Salman, and before the call, we’re having this debate. They say, “You’re going to deal with King Salman. We deal with his brother Mohammed bin Nayef, who’s the intelligence chief, and he’s a great ally for the U.S.”

And I said, “Well, if he’s such a good ally to the U.S, why do we have all these terrorist concerns with Saudi that you guys keep complaining about?”

And I said, “Look, I just want you to know I have a proposal from another guy there who’s the deputy Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman, and he’s saying he wants to do all these things to really change, really big things, that will really make a difference.”

The call gets on the line. President Trump takes the call, speaks to King Salman. It was a pretty rough call because Trump, as you know, it can be very blunt. He basically says, “We want to see changes and we want to see them fast.”

And what King Salman basically says to him is, “We’re ready to lean in. We want to really strengthen the relationship with America. We did not like how it went before and we’re ready to do it.”

And so President Trump says, “Who should my team deal with?” And he says, “Deal with my son, the Deputy Crown Prince, Mohammed bin Salman.”

So, then he says, “Let him deal with Jared.” And the reason why he chose me for is because he knew the other guys weren’t believers, and they’d probably sabotage.

So, I get back to my desk and I have a note from him. We worked basically for 90 days straight to set up this trip. He sent his top guys to Washington. I got every single thing in writing. I couldn’t get people in the White House to come to the meetings to plan on the trip because they basically said, “This is going to be a disaster. We are all going to be embarrassed, and we want Jared to take the blame.”

We’re taking off for the trip. And I’m thinking to myself, why do I always do this to myself? We could have just gone to Mexico and cut a ribbon. What do I have to do this for? So, we go there, and I actually would encourage you to read or watch President Trump’s speech from Riyadh because he basically said, you’ll excuse my French. He says, “Look, I’m not going there to kiss ass.” He says, “I’m going there to kind of lay down markers and say, this is what needs to change and this is what we need to do.” He went there with a very tough, realistic speech, and he basically said, “This is not your problem. This is not our problem. This is all of our problems. We want to get these terrorists out of our homes. Get them out of our mosques. Let’s get them out of this world.” And it was very, very rough. And the king of Saudi Arabia gets up there and says, “There is no glory in death”, which also was a big statement.