Orestes Augustus Brownson (1803–1876), the famed American thinker, understood that political democracy is a failed project from the outset, becaause it could establish a moral framework, which is necessaary for liberty. In other words, how can amoral man be free? And by extention, how can a Godless man be free?

Our Democratic brethren are upon the whole a fine set of fellows, and rarely fail to take whatever turns up with great good humor; otherwise we should expect to lose our ears, if not our head, for the many severe things we intend in the course of our essay to say to them and about them. We shall try them severely; for we intend to run athwart many of their fondly cherished prejudices, and to controvert not a few of their favorite axioms; but we trust they will be able to survive the trial, and to come forth as pure and as bright as they have from that which the Whigs gave them in 1840.

Mentioning this 1840, we must say that it marks an epoch in our political and social doctrines. The famous election [259] of that year wrought a much greater revolution in us than in the government; and we confess, here on the threshold, that since then we have pretty much ceased to speak of, or to confide in, the “intelligence of the people.”The people, the sovereign people, the sovereigns, as our friend Governor Hubbard calls them, during that campaign presented but a sorry sight. Truth had no beauty, sound argument no weight, patriotism no influence.They who had devoted their lives to the cause of their country, of truth,justice, liberty, humanity, were looked upon as enemies of the people,and were unable to make themselves heard amid the maddened and maddening hurrahs of the drunken mob that went for “Tippecanoe, and Tyler too.” It was a sorry sight, to see the poor fellows rolling huge balls, and dragging log cabins at the bidding of the demagogues, who were surprised to fin dhow easily the enthusiasm of the people could be excited by hard cider and doggerel rhymes. And we confess that we could hardly forbear exclaiming,in vexation and contempt, “Well, after all, nature will out; the poor devils,if we but let them alone, will make cattle of themselves, and why should we waste our time and substance in trying to hinder them from making themselves cattle?”

An instructive year, that 1840, to all who have sense enough to read it aright. What happened then may happen again, if not in the same form, in some other form equally foolish, and equally pernicious;and, therefore, if we wish to secure to ourselves and our posterity the blessings of freedom and good government, we must secure stronger guaranties than popular suffrage and popular virtue and intelligence. We for one frankly confess,–and we care not who knows it,–that what we saw during the presidential election of 1840, shook, nay, gave to the winds, all our remaining confidence in the popular democratic doctrines–not measures–of the day; and we confess, furthermore, that we have seen nothing in the conduct of either party since, that has tended to restore it. During the extra session of congress in the summer of 1841, the Democratic delegations in both houses behaved nobly, and acquitted themselves like men; they won the victory for their country, as well as lasting honor and gratitude for themselves from the wise and good everywhere; but our friends seem to have been more successful in gaining the victory than in securing its fruits. The rapid and overwhelming successes which have followed in the state elections,seem to have intoxicated the whole [260] Democratic party, and unless Godsends us some sudden and severe rebuke, there is great danger that we shall go into power again in 1845, without having been in the least instructed by defeat, or purified by adversity. Adversity is easy to bear; it is prosperity that tries the man. But enough of this.

From the fact that popular suffrage, and popular virtue and intelligence, have proved, and are likely to prove, insufficient to secure the blessings of freedom and good government, it must not be inferred that popular suffrage is an evil, and should therefore be abandoned; much less that popular forms of government have proved a failure, and that we should therefore go back to aristocracy or to monarchy. We draw for ourselves no such inference. We have lost no confidence in nor love for popular institutions. The struggle for democratic forms of government has, moreover, been too long and too severe, has enlisted too many of the wise and the good, and been consecrated by too many prayers, sufferings, and sacrifices, to permit us, even if our confidence of ultimate success were altogether less than it really is, to think even for one moment of ceasing to continue it. Humanity never does, and never should, retrace her steps. Her course is onward through the ages. In this career, we have left aristocracy and monarchy behind us; and there let them remain, now and for ever. We may encounter both hunger and thirst in the wilderness; let us trust that the God of our fathers will rain manna upon us, and make water gush from the rock,if need be, rather than like the foolish Israelites sigh to return to the”flesh pots of Egypt,” for we can return to them only by returning to the slavery from which we have just escaped. No: our faces are forward; the promised land is before us; and let the command ran along our ranks, Forward,march!

We assure our democratic brethren, then, in the Old World as well as in the New, that if we have words of rebuke for them, we have no words of consolation or of hope for their enemies. Thank God, we are neither traitors nor deserters; we stand by our colors, and will live or die, fighting for the good old cause, the CAUSE OF THE PEOPLE. But if our general made an unsuccessful attack yesterday, and was repulsed with heavy loss, and all in consequence of not choosing the best position, or of not taking the necessary precautions for covering his troops from the enemy’s batteries, we hope we may in the council held to-day, without any dereliction[261] from duty, advise that the attack be renewed under an officer better skilled to conduct it, or at least that it be renewed from a more advantageous position. We see in the fact that democracy has hitherto failed, no reason for deserting its standard, but of seeking to recruit its forces; or, without figure, we see in our ill success hitherto, simply the necessity of obtaining new and stronger guaranties than popular suffrage can offer, even though coupled with popular intelligence. We would not, we cannot dispense with popular suffrage and intelligence, and we pray our readers to remember this; but they are not alone sufficient, and we must have something else in addition to them, or we shall fail to secure those results from the practical working of the government, which every true-hearted democrats laboring with all his might to secure.

We have not erred in laboring to extend popular suffrage,–though thus far its extension has operated almost exclusively in favor of the business classes, or rather of the money power,–but in relying on it as alone sufficient. There is not a tithe of that virtue in the ballot-box which we, in our Fourth-of-July orations and caucus speeches, are in the habit of ascribing to it. The virtue we have been accustomed to ascribe to it, we have claimed for it on the ground that the people always know what is right and will always act up to their knowledge. That is to say,suffrage rests for its basis, as a guaranty of freedom and good government,on the assumed intelligence and virtue of the people. Its grand maxim is, “The people can do no wrong.” Now, this may be very beautiful in theory,but when we come to practice, this virtue and intelligence of the people is all a humbug. We beg pardon of the sovereign people for the treasonable speech; but it is true, true as Holy Writ, and there is neither wisdom nor virtue in pretending to the contrary. Perhaps, however, our remark is not quite true, in the sense in which it will be taken, without word or two by way of explanation.

To the explanation, then. We are in this country, we democrat sand all, most incorrigible aristocrats. We are always using the word people in its European sense, as designating the unprivileged many, in distinction from the privileged few. But this sense of the word is with us really inadmissible. We, we the literary, the refined, the wealthy, the fashionable,we are people as well as our poorer and more coarsely mannered and clad neighbors. We are all [262] people in this country, the merchant,the banker, the broker, the manufacturer, the lawyer, the doctor, the office-holder,the office-seeker, the scholar, and the gentleman, no less than the farmer,the mechanic, and the factory operative. We do not well to forget this.For ourselves, we always remember it, and therefore when we speak slightingly of the intelligence and virtue of the people, it is of the whole people,not of any particular class; in a sense which includes necessarily us who speak as well as those to whom we speak. When, then, we call what is usually said about the virtue and intelligence of the people all a humbug, we do not use the word in its European sense, and mean to speak disparagingly of the intelligence of plebeians as distinguished from patricians, of the “base-born” as distinguished from the “well-born;” for the distinctions here implied do not exist in this country, and should not be recognized even in our speech. When it comes to classes, we confess that we rely as much on the virtue and intelligence of proletaries as on the virtue and intelligence of capitalists, and would trust our mechanics as quick pandas far as we would our merchants and manufacturers.

There is, if we did but know it, arrant aristocracy in this talk which we hear, and quite too frequently in our own ranks, about the virtue and intelligence of the people. Who are we who praise, in this way, the people? Are we ourselves people? And when we so praise them, dowel feel ourselves below them, and looking up to them with reverence? Or do we feel that we are above them, and with great self-complacency, condescending to pat them on the shoulder, and say, after all, my fine fellows, you are by no means such fools as your betters sometimes think.” If we were in England, where there is a recognized hereditary aristocracy, and where the word people is used to designate all who do not belong to the nobility or privileged class, we could understand and even accept what is said about the virtue, intelligence, and capacity of the people; for there it would be appropriate and true. There it would simply mean that the unprivileged classes–the commons–are as able to manage the affairs of the government, and as worthy of confidence, as are the nobility, they who are born legislators; which we hold to be a great and glorious truth,worthy and needing to be preached, even to martyrdom, in every country in which the law recognizes a privileged class. But here it has no meaning,or one altogether inappropriate, [263] false and pernicious. To praise the people here for their virtue and intelligence is either to show that we feel ourselves above them, and praise them solely because we wish tousle them; or it is simply praising ourselves, boasting of our own virtue, intelligence, and capacity. The people should beware of the honeyed voices perpetually sounding their praise. He who in a monarchy will flatter the monarch, or in an aristocracy will fawn round the great, will in a democracy flatter the people; and he who will flatter the people in a democracy,would in an aristocracy fawn round the great, and in a monarchy, flatter the monarch. The demagogue is the courtier adapting himself to circumstances.And yet, flattery is so sweet, that he who can scream loudest in praise of the sovereign people, and whose conscience does not stick even at the blasphemy of Vox populi est vox Dei, will be pretty sure of receiving the largest share of their confidence and favor–another proof of their virtue, intelligence, and capacity!

One thing, by the way, we must own,–the people will bear with more equanimity to be told of their faults than will other sovereigns, or we ourselves should be drawn and quartered for our reiterated treason. But, if they would only lay our treason to heart, and profit by it, we would willingly consent to be drawn and quartered. But, alas! we may speak,and our good-natured sovereign will merely smile, call for his coffee and pantoufles, sip the beverage, throw himself back in his easy-chair, and doze. It is a virtue to commend him, and whoso does not, he disregards. Whoever among us expresses any want of confidence in the people, notwithstanding their apparent forbearance, is supposed to be their enemy, and is sure to be read out of the Democratic party; or to be laid up on the shelf, till some difficulty occurs in which his strong sense and stern integrity become indispensable. But after all, what is the ground of this confidence in the people? A strong party is springing up among us, which builds entirely upon this confidence, and says that if the people were only left to themselves they would always do right; and that all the mischief arises from our attempting to govern the people, and to prevent them from having their own way. Hence,say they, let us have as little government as possible, or rather let us have no government. “All we want government for,” said Dr. Channing one day to the writer, “is simply to undo what government has done.” If the people are worthy of all the [264] confidence demanded, why not yield it? Why not rely on the people? Why seek to bind them by constitutions, and to control them by laws, which in the last resort the military may be called in to enforce? If the people always know the right, and always act up to their intelligence, government is a great absurdity. But we do not find our friends generally confiding in the people to this extent, though the doctrine they preach goes thus far. As much as they confide in the people,they do not feel willing to leave them to vote in their own way. We have our caucuses, and various and complicated machinery, without which we feel very sure that the people would not vote at all, or if voting, not on our side. In a majority of cases, we are so afraid that the people will not vote, or not vote aright, that we, through committees, caucuses, conventions, nominations, party usages, &c., so do up all the work, that the voting becomes a mere form, almost a farce–yet we preach confidence in the people!

But once more. What is the ground of this confidence in the virtue, intelligence, and capacity of the people? Do we really mean to say that the people acting individually or collectively never do, and never can do any wrong? Whence, then, comes all this wrong of which everybody is complaining? The people are virtuous,–whence, then, the vice, the crime, the immorality, the irreligion which threaten to deluge the land? What need of swords, pistols, bowie knives, jails, penitentiaries, pains, penalties, laws, judges, and executioners? What need of schools, churches, teachers, preachers, prophets, and rulers? Nobody is so mad as really to pretend that nothing among us is wrong. Let alone private life, go merely into public life, enter the halls of justice and legislation–is all right here? No; everybody complains; everybody finds somewhat to condemn; some one thing, some another. And yet who has done this of which everybody is complaining? The people. What hear we from every quarter, but denunciations of this or that measure of public policy; of the profligacy of the government,or of its administration? And after all who is in fault? Whose is the government? The people’s. The people are sovereign, and of course the government and its administration, the laws and their execution, are just what the people will they should be. Is it not strange, if the people always perceive the right, and perceiving, always do it, that nevertheless where they are supreme,and what ever is done, is done by them, there yet should be so much wrong done? [265]

But touching the intelligence of our American people, we would ask with still more emphasis, Where have they shown it? Was it in the presidential campaign of 1840? Have they shown it in the several states in contracting abroad some two hundred millions of dollars or more of state and corporation debts? Have they shown it in introducing, extending and sustaining almost from their infancy the ruinous system of paper money? Do they show it by advocating the falsely-so-called American system–the”protective policy,” thereby crippling commerce, and enslaving the operative,for the very questionable benefit of a few manufacturing capitalists? Do they show it in their insane support of the immense system of corporations which spread over the country like a vast network, and which, flooding the market with stock, gives to a few individuals who have contrived to maintain their credit, the means of controlling and laying under contribution the whole industrial activity of the country? Have they shown it, in their very general condemnation of the only measure which would separate the revenues of the government from the general business operations of individuals,and secure to the government that financial independence, without which it ceases to be government, and becomes merely an instrument in the hands of one portion of the community for plundering the other? We demand of the statesmen who publicly boast, that during their whole continuance in office, “they have made it their duty to ascertain and bow to the will of the people;” –we demand of them, wherein they find this infallible popular intelligence on which they bid us rely? The people, we shall be told, rejected the elder Adams, elected and sustained Mr. Jefferson. Be it so, and yet, will any one tell us wherein the policy of Mr. Jefferson, so far as it bore on the practical relations of the people, and their every-day business interests, differed essentially from that of Mr. Adams? They rejected the old federal theory of government, it is true, and adopted the democratic; but it may be a very serious question, whether the latter theory, as the people understand it, is so much in advance of the former as we sometimes imagine. We shall be told that the people sustained General Jackson in his anti-bank policy; but it was General Jackson and not his policy,for they refused to sustain his successor, who pursued with singular consistency and firmness the same policy; and they would have sustained a new bank,had not Mr. Biddle’s bank failed at the very moment [266] it did, spreading alarm and distress through the land. Nine tenths of our business men even now fancy that we can add to the wealth of the country by increasing the paper circulation, and attribute the present embarrassments of the country to the want of confidence, when in fact these embarrassments have resulted almost solely from an excess of confidence; and can be relieved, not by any increase of confidence, but of that which gives to confidence a solid basis–solid capital.

In fact, no measure of public policy can be proposed, so absurd or so wicked, but it shall find popular support. What could be a more bare-faced violation of the constitution, more profligate, or more absurd as a measure of public policy, than the act of congress distributing the proceeds of the sales of the public lands among the several states? And yet where has it aroused any popular indignation? How many of even the Democratic states have had the virtue to fling back the bribe that was offered them? Has New York? Pensylvania? Ohio? Illinois? Missouri? Mississippi.? Georgia? Virginia? Maine? We recollect now, out of all the Democratic states, only three–South Carolina, Alabama, and New Hampshire–that have had the virtue to refuse to receive their portion of the spoils. A good Democrat introduced resolutions into the Massachusetts legislature declaring the act unconstitutional, and that the state ought not to accept its portion of the money; but he was induced by his own party, while agreeing with him in the unconstitutionality of the act, to amend his resolutions so as to leave out the clause which required the state to refuse to receive money unconstitutionally distributed. And what is remarkable, the amendment was proposed and urged by one of the most influential members of the party in the legislature, and who has been regarded for years as the leader of the ultra or radical portion of the Democratic party in the state. So little popular opposition has this measure encountered, a measure which would have been, no doubt, cheerfully acquiesced in by a large majority of the people, as the settled policy of the country, had it not been defeated by the presidential veto.

We might go even further, and venture to predict that the assumption of the state debts by the federal government, all unconstitutional and wicked as such assumption would be, will yet be adopted. There are so many stockholders, both at home and abroad, interested in its adoption,[267] that it must come at last, unless Providence interpose in our behalf.The people,–we mean the mass of the people, of the constituencies–are now, we fear, prepared for it, and nothing but the virtue of a few public men now delays it. If it be ultimately defeated, it will be through the influence of these few patriotic individuals; perhaps, nay, most likely,by the executive veto. The merchants to a considerable extent will sustain the measure, because it is one which will help to sustain or facilitate their credit abroad; the manufacturers will sustain it, because it will afford a pretext for the imposition of high duties on foreign imports;the operative and the farmer must sustain it, because the first depends on the manufacturer and trader for employment, and the last for the sale of his produce; against these the planters will hardly be able to sustain themselves, especially when several of the planting states are themselves to be directly relieved by assumption from the embarrassments which now cripple their energies. Where, then, is the power to defeat the measure?Yet we go on lauding the virtue and intelligence of the people!

Let us return for a moment to what is called “the protective policy.” The Lynn shoemaker clamors for protection, for high duties to diminish foreign imports and to secure to him the monopoly of the home market. If he can only exclude French shoes, he shall then have this monopoly.Very well. Where does he, and where must he find the principal market for his shoes? South and West. The value of that market to him, then, will depend on the ability of the South and West to buy shoes. Whence this ability?It depends, of course, on the ability of the South and West to sell their own productions. The principal market for western produce is at the South.The ability of the West to buy Lynn shoes depends, then, on its ability to sell its productions to the South. Whence, then, we must ask again,the ability of the South to buy western produce and Lynn shoes? In its ability to sell its rice, cotton, and tobacco to the foreigner. Whence the ability of the foreigner to buy the rice, cotton, and tobacco of the South? In his ability to sell his own productions or manufactures to us.If we will not buy of him, he cannot buy of us. Consequently, just in proportion as the Lynn shoemaker places an impediment in the way of the foreigner selling to us, does he place an impediment in the way of his selling his shoes to the South and West. In proportion as he secures, by [268] prohibitory duties, the monopoly of the home market, he diminishes its value, by diminishing the ability of the people to consume. Here, at best, he loses on the one hand all he gains on the other. Yet we boast of the intelligence of the Lynn shoemaker, and his intelligence, by the by, is above the average intelligence of the country.

But, absurd as the protective policy would be under any state of things,–implying that industry can be more energetic and efficient if bound than when left to the free use of its limbs,–it is doubly so when coupled, as we have coupled it, with the paper money system–a system which, though somewhat shaken, the mass of the people are still attached to, and the abolition of which scarcely a public man who values his reputation dare even propose. Very few of the people have ever thought of inquiring into the operations of the two systems when combined. In the first place,the paper money system, by depreciating our currency below that of foreign nations, operates as a direct premium, to the percentage of the depreciation,in favor of the foreign manufacturer; because the foreigner sells to us at the high prices produced by our depreciated currency, but buys of us,always, according to his own appreciated currency. This, for years in our trade with England, very nearly neutralized the tariff intended to protect our own manufactures.

In the next place, the tariff operating with the banking system tends to increase instead of diminishing the advantage of the foreign manufacturer. The first effect of a protective tariff, if it have any effect at all, is no doubt to diminish the imports, and to bring them, in fact, below the exports; which throws the balance of trade in our own favor.This cuts off all foreign demand for specie, and sends specie into the country, if needed. This, freeing the banks from all fear of a demand for specie to settle up foreign balances, and rendering it easy for them to obtain specie from abroad, if necessary, enables them to employ their capital in discounting freely to business men, even to speculators, and to throw out their paper to an almost unlimited extent. This expands, that is, depreciates the currency; prices rise; and the foreign manufacturer is able to come in over our own tariff, sell his goods at our enhanced prices, pay the duties, and pocket a profit. This, in turn, swells the revenue, which,if deposited in the banks, becomes the basis of additional discounts, which expand still more the currency, enhance prices still more, till the whole land [269] is flooded with foreign imports, which shall, as we have seen in our own case, notwithstanding our agricultural resources, extend even to corn, barley, oats, and potatoes; thus crushing not only our home manufactures,but the interests of every branch of industry but that of trade; and at length even that by destroying its very basis. This is no theory, it is fact; it is our own bitter experience as a people, from the terrible effects of which we are not yet recovered; and still we hold on to the policy,and the majority of the American people, even today, after all their experience,believe in the wisdom of continuing both systems!

But enough of this. We have heard so much said about the wisdom and intelligence of the people, that we perhaps are a little sore on the subject, and may therefore be disposed to exaggerate their folly and wickedness. But we have seen enough to satisfy us, that if we mean by democracy the form of government that rests for its wisdom and justice on the intelligence and virtue of the people alone, it is a great humbug.The facts we have brought forward prove it so; nay, more, that in destroying all guaranties, and in relying solely on the wisdom and virtue of the people,we are destroying the very condition of good government.

We may be told, as we doubtless shall be, by our democratic friends, that the errors we have pointed out, were not, and are not the errors of the people. Of whom then? “Of the people’s masters; of bankers,stock-jobbers, corporators, selfish politicians, &c.” And who are these? Are they not people? And how came they to be the people’s masters? And why do the people, if they are so wise and virtuous, submit to be controlled by them? We shall be told, and truly, that the principal measures or acts we have condemned, have been supported, not by the Democratic party, but by the Federalists and Whigs. But who pray are Federalists and Whigs? Are they not people just as much as are the Democrats? Is not what is done by them as much done by the people, as what is done by us? In speaking of the people we must include all parties, for we are as we have seen,in this country, all people, and the most numerous party is always the most popular. The American people are as responsible for what the Whigs do, as they are for what the Democrats do. So we cannot throw off from the people the responsibility of any of the systems of policy the government adopts, by saying it was adopted by this or that party. [270]

We of course shall not be understood in these remarks to intend any thing against the general wisdom and justice of the aims and measures of the Democratic party. As we understand its aims and measures, they are wise and patriotic, just and philanthropic. The Democratic party, at heart, is opposed to paper money, to a high protective tariff, to the growing system of corporate or associated wealth, and to a consolidated republic; and is in favor of the constitutional currency, free-trade, state rights, strict construction of the constitution, low taxes, an economical administration of the government, and the general melioration in the speediest manner possible of the moral, intellectual, and physical condition of the poorest and most numerous class. Taking this view of its aims and its measures,we must needs hold it to be the party of the country and of humanity. As such we are with it and of it, and no earthly power shall prevent us from laboring to advance it. But the doctrines which some of its members put forth on the foundation and authority of government, and which threaten to become popular in the party, nay, its leading doctrines, we own we do not embrace and cannot contemplate without lively apprehensions for the fate of liberty, civil and personal.

The great end with all men in their religious, their political,and their individual actions, is FREEDOM. The perfection of our nature is in being able “to look into the perfect law of liberty,” for liberty is only another name for power. The measure of my ability is always the exact measure of my freedom. The glory of humanity is in proportion to its freedom. Hence, humanity always applauds him who labors in right-down earnest to advance the cause of freedom. There is something intoxicating to every young and enthusiastic heart in this applause–always something intoxicating, too, in standing up for freedom, in opposing authority, in warring against fixed order, in throwing off the restraint of old and rigid customs, and enabling the soul and the body to develop themselves freely and in the natural proportions. Liberty is a soul-stirring word. It kindles all that is noble, generous, and heroic within us. Whoso speaks out for it can always be eloquent, and always sure of his audience.One loves so to speak if be be of a warm and generous temper, and we all love him who dares so to speak.

In consequence of this, we find our young men–brave spirits they are too–full of a deep, ardent love of liberty, and ready to do battle for her at all times, and against any [271] odds. They, in this, address themselves to what is strongest in our nature, and to what is noblest; and so doing become our masters, and carry us away with them. Here is the danger we apprehend. We fear no attacks on liberty but those made in the name of liberty; we fear no measures but such as shall be put forth and supported by those whose love of freedom, and whose impatience of restraint,are altogether superior to their practical wisdom. These substitute passion for judgment, enthusiasm for wisdom, and carry us away in a sort of divine madness whither we know not, and whither, in our cooler moments, we would not. It is in the name of liberty that Satan wars successfully against liberty.

We mean not here to say that we can have too much liberty, or that there is danger that any portion of our fellow-citizens will become too much in earnest for the advancement and security of liberty. What we fear is, on the one hand, the misinterpretation of liberty, and, on the other, the adoption of wrong or inadequate measures to establish or guaranty it. We fear that a large portion of the younger members of the Democratic party do misinterpret liberty. If they analyze their own minds, they will find that they are yet virtually understanding, liberty as we did when the great work to be done was to free the mass of the people from the dominion of kings and nobilities. They will find, we fear, that they have not thought,that in order to secure freedom any thing more was necessary, than to establish universal suffrage and eligibility, and to leave the people free to follow their own will, uncontrolled, unchecked. Hence, liberty with them is merely political. Where all are free to vote and to be voted for, there is all the freedom they contemplate.

Perhaps this is stated too positively. Perhaps it would be truer to say, that they do not see that any thing more is necessary,in order to render every man practically free; than the establishment of a perfectly democratic government. Where all the people take part in the government, are equally possessed of the right of suffrage and that of eligibility, and where the people are free to take any direction, at anytime, that the majority may determine, they suppose that there perfect freedom is as a matter of course. But this we have seen is not the fact,and cannot be the fact till the virtue and intelligence of the people are perfect, instead of being, as they now are, altogether imperfect, [272]and, in reference to what they should be, in order to render certain the end contemplated, as good as no virtue and intelligence at all. But ignorant of this fact, confiding in the virtue and intelligence of the people, feeling that all the obstacles liberty encounters are owing to the fact that the will of the people is not clearly and distinctly expressed, they labor to remove whatever tends in their judgment to restrain the action of the people, or the authoritative expression of the will of the majority. But when they have removed all these restraints, broken all barriers, and obtained all open field and fair play for the will of the people, what is thereto guaranty us the enjoyment of liberty?

This question leads us to the point to which all that we have thus far said has been directed. We solemnly protest against construing one word we have said into hostility to the largest freedom for all men;but we put it to our young friends, in sober earnest too, whether with them freedom is something positive; or whether they are in the habit of regarding it as merely negative? Do they not look upon liberty merely as freedom from certain restraints or obstacles, rather than as positive ability possessed by those who are free? They assume that we have the ability,the power, both individually and collectively,–when once the external restraints are taken off,–to be and to do all that is requisite for our highest individual and social weal. Is this assumption warrantable? Is man individually or socially sufficient for himself? Should not our politics,as well as our religion, teach us that it is not in man that walketh to direct his steps, and that he can work out his own salvation, only as a higher power, through grace, works in him to will and to do.

This bring[s] us back to the old question, Are the people competent to govern themselves? What we have said concerning the virtue and intelligence of the people, has been said for the express purpose of proving that they are not competent to govern themselves. We confess here to what we know in the eyes of our countrymen is a “damnable” political heresy, but, an’ they should burn us at the stake, we must tell them this notion of theirs about self-government is all moonshine; nay, a very Jack o’ Lantern, and can serve no better purpose, if followed, than to lead them from the high road, and plunge them in the mire or the swamp from which to extricate themselves will be no easy matter. The very word itself implies a contradiction. There is a government only where there is that which governs, and [273] that which is governed. In what is called self-government, the governor and the governed are one and the same, and therefore no government. That which governs is that which is governed; but how can the governor be the governed, or the governed the governor? We assure our readers, we are not playing on terms, nor quibbling about words. In this doctrine of self-government, the people as the governed,are absolutely indistinguishable from the people as governors. Tell us,then, in what consists the government? Tell us wherein this doctrine of self-government differs from no-government? But do we not need government?

“But you mistake the question. The question is not, Are the people competent to govern themselves? but, Are they able, of themselves, to institute and maintain wise and just civil government?” They who put the question in this form, admit that government is necessary; but they contend that the people, seeing this, will institute government, and voluntarily put a restraint on their own power. This is what we have done in this country. The people here are sovereign, but they have drawn up and ordained certain constitutions or fundamental laws, which limit their sovereignty and prescribe the mode in which it shall be exercised.

But who or what guaranties the constitution? In other words, assuming the constitution to be adopted, what is there back of the constitution that compels its observance, or prevents its violation? In short, what is the basis, the support of the constitution? A constitution,which is merely a written constitution, is only so much waste paper. There is always needed a power that shall make the written constitution the real,the living constitution of the people. Where in your democracy is this power? In the people unquestionably. “The people make the constitution,and they will have respect unto the work of their hands, and will therefore protect the constitution.” Admirable! The people voluntarily adopt a constitution,which constitution when adopted has no power to govern them, but what they voluntarily concede to it! Pray, wherein does this differ from no constitution at all? If the people are competent to frame the constitution and to maintain it, they are competent to govern themselves without the constitution, which we have already seen is not the fact. The constitution, if entrusted to the voluntary support of the people themselves, is worth nothing; for if the people will voluntarily abstain from doing what the constitution forbids,they would voluntarily [274] abstain from doing it even were there no constitution.The constitution in this case can give no additional security, for it gives nothing that we should not have without it.

What we insist on here is, that the constitution, if it emanate from the people, and rest for its support on their will, is absolutely indistinguishable from no constitution at all. What we want is something which shall govern. This, we are told, is the constitution. But the constitution, if it emanate from the people, and have no support but their will, is the people; and whatever power it may have, is after all only the power of the people. But it was the people, and not the people as individuals, but the people as the state, or body politic, that needed to be governed; and we have, even with the constitution, only the people with which to govern the people. They who tell us that the people will voluntarily impose and maintain the necessary restraints on their own will, do then by no means relieve us of our difficulties; for the will imposing the restraints,is identically the will to be restrained; and, therefore, they give us in the state but one will, and that will, since it imposes all restraints that are imposed, is really itself unrestrained. If the people are to be governed at all, there must be a power distinct from them and above them,sufficient to govern them. Now, can the people create this power? Will theyvoluntarily place a power above them, which can govern them;and therefore to which they must submit, whether they choose to submit or not? If so, we must cease, when they have so done, to talk of self-government,or of government by consent of the governed; for this power, whatever it be, wherever lodged must be, when constituted, distinct from the people and their sovereign. If the people have a sovereign, they cannot be themselves sovereign.

In all their speculations, they who differ from us, overlook the important fact that government is needed for the people as the state,as well as for the people as individuals. They assume, consciously or unconsciously, that the people, as the body politic, need no governing, and that, so viewed, they have in themselves a sort of inherent wisdom and virtue, which will lead them always to will and ordain what is wise and just, and only what is wise and just. They therefore seek government,not for the people as the body politic, but for the people as individuals.That is to say, they [275] seek not to restrain the power of the sovereign,but are willing to leave it absolute. Hence they proclaim the absolute sovereignty of the people, never ceasing to repeat, in season and out of season, that all legitimate power emanates from the people, and that the chief glory of the statesman is to find out and conform to the will of the people. We do not err in declaring that this is that theory of democracy which is becoming the dominant theory of all parties in the country. But,when we have reduced this theory to practice, when we have made the people supreme in the sense, and to the extent here implied, where is the practical guaranty for freedom? On what can we rely to protect our rights as men? Nay, what are we all in this case, as individuals, but the veriest slaves of the body politic? We have talked of certain inalienable rights, that is, rights which we possess by virtue of the fact that we are men, which we cannot ourselves surrender up, and which cannot be taken from us; but what is the use of talking about rights when we have no power to maintain them? My rights are worth nothing beyond my might to assert and maintain them against whosoever or whatsoever would usurp them.

Democracy is construed with us to mean the sovereignty of the people as the body politic; and the sovereignty of the people again is so construed that it becomes almost impossible to draw any line of distinction between the action of the people legally organized as the state, and the action of the people as a mob. The people in a legal or political sense, properly speaking, have no existence, no entity, therefore no rights,no sovereignty, save when organized into the body politic; and then their action is legitimate only when done through the forms which the body itself has prescribed. Yet we have seen it contended, and to an alarming extent,that the people, even outside and independent of the organism, exist as much as in it, and are as sovereign; and that a majority–aye, a bare majority counted by themselves–of the inhabitants of any given territory, have the right, if dissatisfied with the existing organism, to come together,informally, without any reference to existing authorities, and institute a new form of government, which shall legitimately supersede the old, and to which all the inhabitants of the territory shall owe allegiance!Admit this doctrine, and we ask our friends who have, we must believe,hastily and without reflection adopted it, what distinction they would make between the people and the mob? [276]

Let us look at this doctrine of popular sovereignty for a moment. We say, for instance, if the people of Massachusetts do not like their present form of government, they may make such alterations, acting through the existing forms, as they choose. These alterations, wise or unwise, would be legal, and binding upon the citizen. But suppose a number of individuals, dissatisfied with the existing provisions of the constitution,should call a meeting of individuals, who should frame a new constitution,send it out, and indeed obtain for it a majority of the votes in what is now the state of Massachusetts; this new constitution, according to the doctrine we are considering, would be the supreme law of the land. Be it so. But why restrict this to a majority of the inhabitants of the state?The men who are forming the new constitution must, of course, assume the nullity of the old, at least so far as their action is concerned, and also so far as it concerns the adoption of the new constitution. Assume the nullity of the constitution, and where would be Massachusetts? There would be, in a political sense, no Massachusetts at all. Why, then, cannot the new doctrine be applied to a section as well as to the whole territory?Why may not the majority of the inhabitants of what is now a county, a town, or a school district, if they choose, set up the same theory, and form and enforce a constitution for themselves? Outside of the existing organism there is no state, county, town, or school district, for these are all creations of the existing organism. Then we see not what there is to prevent the application of the doctrine to themselves by any number of individuals who choose. Nay, what is there to prevent its adoption by single individuals, and to make it not absurd for an individual to say to the state, “I disown you; I am my own state; I ask nothing of you, and I will concede you nothing. I am a man; I am my own sovereign, and you have no authority over me but by my consent. That consent I have never given; or if I have heretofore given it, I now withdraw it. You have, then,no right over me, and if you attempt to control me you are a tyrant.” This is no fancy sketch. This language we have actually heard used in sober earnest by one who knew very well what he was saying, and who so strongly believed in what he was saving, that he has chosen himself to be put in gaol rather than to acknowledge the authority of the state by paying a tax. Once proclaim the absolute sovereignty of the people, acting without[277] reference, to political organisms, that is, as a mass of individuals,or once proclaim, as the governor of New Hampshire does in his letter to the governor, or acting governor of Rhode Island, that the people are”sovereigns,” that is, making, each individual a sovereign, and you can exercise through the state no authority over any man, not even to punish him for the greatest social offence, without his consent. Your collector goes with his tax bill, the individual rightly exclaims, “Away, I know you not.” A family is living in open violation of the laws of God, you send your police to arrest them; they have a right to answer, “We are sovereign;we do not acknowledge our obligation to obey your sovereign; we are not accountable to your laws; we have formed our own constitution, and make our own laws; we hold to self-government.” The good sense of all parties, of course, would arrest the application of the doctrine long before it could come to this extent; but to this extent the doctrine we combat may be legitimately carried and in this fact we may and ought to see its radical unsoundness.

For ourselves, we object to the definition of democracy, which makes it consist in the sovereignty of the people. The sovereignty of the people, in the sense commonly contended for, we own we do not admit.The people, as an aggregate of individuals, are not sovereign, and the only sense in which they are sovereign at all, is when organized into a state, or body politic, and acting through its forms. No action of the inhabitants of a given territory, even if it include ninety-nine out of a hundred of all the individuals, is done by the PEOPLE, unless done in and through the forms prescribed by the political organism; and all action done in opposition to that organism, no matter how many are engaged in it, is the action of the mob, disorderly, illegal, and to a greater or less degree criminal, treasonable in fact, and as such legitimately punishable.

We do not wish to be too severe on the advocates of the doctrine we oppose. It has been with most of them only a momentary error, and which, though pelting us unmercifully for exposing it, they will quietly abandon, and without confessing it, feel shame for ever having advocated. Confident of this, we give them leave to say all the hard things of us they please; for we acknowledge that for a moment we too fell into the same error. Our sympathy with the end which we saw a portion of our friends struggling [278] to gain, and by means which were justifiable only on the doctrine in question, blinded us for a time, as we presume it has others,to the real character of the doctrine itself. Let this confession suffice for us and for our brethren. They of course will not accede to it, but we venture to predict, that, as the excitement of the struggle to which we have alluded subsides, and matters reassume their orderly and peaceful course, there will be found few so bold as to reiterate the doctrine.

But the fact that this doctrine has been put forth, in sober earnest, by men in high places as well as by men in low places, is itself an argument in our favor, and goes to prove that the people are not to be relied on so implicitly as some of our democratic friends pretend.The case we have had in mind, strikingly illustrates the sort of danger to which, under a democracy, interpreted to mean the absolute sovereignty of the people, we are peculiarly and at all times exposed. The ends the people seek to gain, are, we willingly admit, for the most part just and desirable; but the justice and desirableness of the end, almost always blind them to the true character and tendency of the means by which they seek to gain it. They become intent on the end, so intent as to be worked up to a passion for it,–for the people never act but in a passion,–and then in going to it, they break down every thing which obstructs or hinders their progress. Now, what they break down, though in the way of gaining that particular end, may after all be our only guaranty of other ends altogether more valuable. Here is the danger. What more desirable than personal freedom? What more noble than to strike off the fetters of the slave? Aye, but if, in striking off his fetters, you trample on the constitution and laws, which are your only guaranty of freedom for those who are now free, and also for those you propose to make free, what do you gain to freedom? Great wrong may be done in seeking even a good end, if we look not well to the means we adopt. Philanthropy itself not unfrequently is so intent on the end, that in going to it, it tramples down more rights than it vindicates by success. We own, therefore, that the older we grow, and the longer we study in that school, the only one in which fools will learn, the more danger do we see in popular passions, and the less is our confidence in the wisdom and virtue of the people.

“But what is our resource against all these evils? What [279] remedy do you propose?” These are fair questions, but we do not propose to answer them now. We may hereafter undertake to do it, and what we shall have to say will be arranged under the heads of the constitution, the church, and individual statesmen. Without an efficient constitution, which is not only an instrument through which the people govern, but which is a power that governs them, by effectually confining their action to certain specific subjects, there is and can be no good government, no individual liberty. Without the influence of wise and patriotic statesmen, whose importance,in our adulation of the people as a mass, we have underrated, and without the Christian church exerting the hallowed and hallowing influences of Christianity upon the people both as individuals and as the body politic,we see little hope, even with the best constitution, of securing the blessings of freedom and good government. But these are matters into the discussion of which we cannot now enter. Our purpose in this article has been to draw the attention of our political friends to certain heresies of doctrine which are springing up amongst us, and enlisting quite too much sympathy,and which we believe pregnant with mischief.

Democracy, in our judgment, has been wrongly defined to be a form of government; it should be understood of the end, rather than of the means, and be regarded as a principle rather than a form. The end we are to aim at, is the freedom and progress of all men, especially of the poorest and most numerous class. He is a democrat who goes for the highest moral, intellectual, and physical elevation of the great mass of the people, especially of the laboring population, indistinction from a special devotion to the interests and pleasures of the wealthier, more refined, or more distinguished few. But the means by which this elevation is to be obtained, are not necessarily the institution of the purely democratic form of government. Here has been our mistake. We have been quite too ready to conclude that if we only once succeed in establishing democracy,–universal suffrage and eligibility, without constitutional restraints on the power of the people,–as a form of government, the end will follow as a matter of course. The considerations we have adduced,we think prove to the contrary.

In coming to this conclusion, it will be seen that we differ from our friends not in regard to the end, but in regard to [280]the means. We believe, and this is the point on which we insist, that the end, freedom and progress, will not be secured by this loose radicalism with regard to popular sovereignty, and these demagogical boasts of the virtue and intelligence of the people, which have begun to be so fashionable.They who are seeking to advance the cause of humanity by warring against all existing institutions, religions, civil, or political, do seem to us to be warring against the very end they wish to gain.

It has been said, that mankind are always divided into two parties, one of which may be called the, stationary party, the other the movement party, or party of progress. Perhaps it is so; if so, all of us who have any just conceptions of our manhood, and of our duty to our fellow men, must arrange ourselves on the side of the movement. But the movement itself is divided into two sections,–one the radical section,seeking progress by destruction; the other the conservative section, seeking progress through and in obedience to existing institutions. Without asking whether the rule applies beyond our own country, we contend that the conservative section is the only one that a wise man can call his own. In youth we feel differently. We find evil around us; we are in a dungeon; loaded all over with chains; we cannot make a single free movement; and we utter one long,loud, indignant protest against whatever is. We feel then that we can advance religion only by destroying the church; learning only by breaking down the universities; and freedom only by abolishing the state. Well, this is one method of progress; but, we ask, has it ever been known to be successful?Suppose that we succeed in demolishing the old edifice, in sweeping away all that the human race has been accumulating for the last six thousand years, what have we gained? Why, we are back where we were six thousand years ago; and without any assurance that the human race will not reassume its old course and rebuild what we have destroyed.

As we grow older, sadder, and wiser, and pass from idealists to realists, we change all this, and learn that the only true way of carrying the race forward is through its existing institutions. We plant ourselves, if on the sad, still on the firm reality of things, and content ourselves with gaining what can be gained with the means existing institutions furnish. We seek to advance religion through and [281] in obedience to the church; law and social well-being through and in obedience to the state. Let it not be said that in adopting this last course, we change sides, leave the movement, and go over to the stationary party. No such thing. We do not thus in age forget the dreams of our youth. It is because we remember those dreams, because young enthusiasm has become firm and settled principle,and youthful hopes positive convictions, and because we would realize what we dared dream, when we first looked forth on the face of humanity, that we cease to exclaim “Liberty against Order,” and substitute the practical formula, “LIBERTY ONLY IN AND THROUGH ORDER.” The love of liberty loses none of its intensity. In the true manly heart it burns deeper and clearer with age, but it burns to enlighten and to warm, not to consume.

Here is the practical lesson we have sought to unfold. While we accept the end our democratic friends seek, while we feel our lot is bound up with theirs, we have wished to impress upon their minds,that we are to gain that end only through fixed and established order; not against authority, but by and in obedience to authority, and an authority competent to ordain and to guaranty it. Liberty without the guaranties of authority, would be the worst of tyrannies.

(1843)

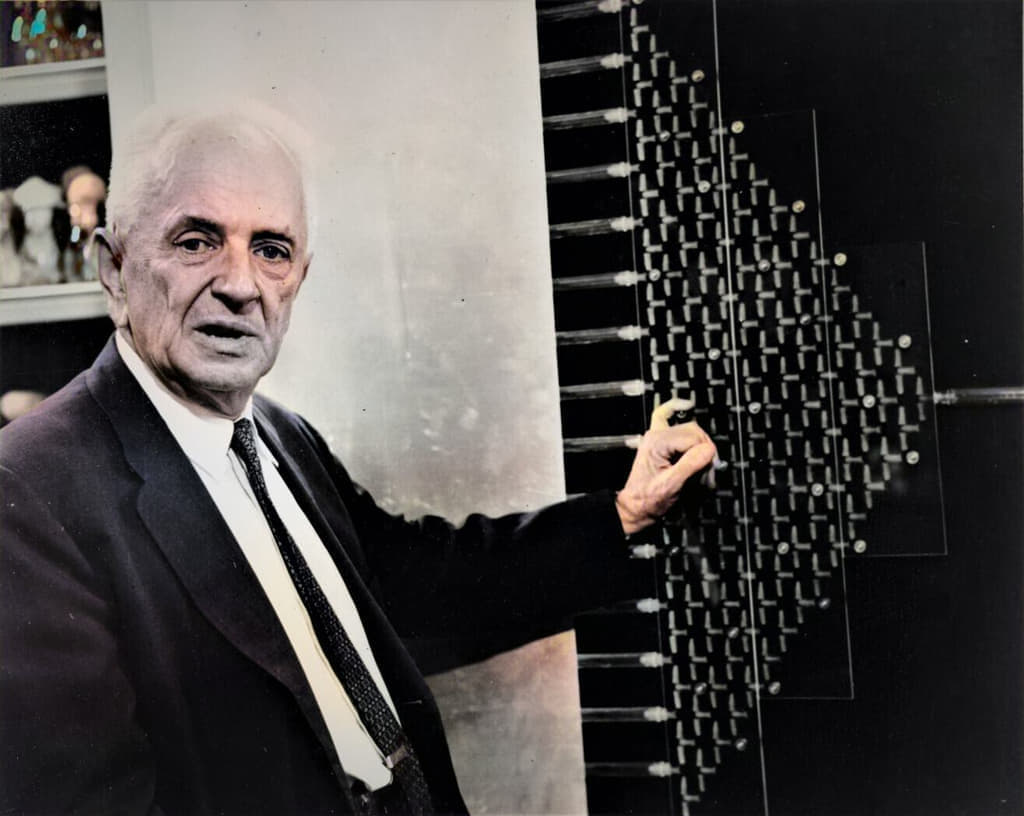

Featured: Orestes Augustus Brownson, by George Peter Alexander Healy; painted in 1863.