In 1965, a book entitled, Sociologie des maladies mentales (Sociology of Mental Illnesses) by Georges Bastide was published. This book, densely written, was hailed, upon its publication, by the ethnopsychiatrist Georges Devereux, by the psychiatrist Robert Castel and even by the sociologist Alain Besançon, who was particularly laudatory: “Vast readings, patient clarification of entangled concepts, sharply critical of the results, confrontation with what is confrontable, bold conclusions as to the substance, modest in expression.”

What is True

But Georges Bastide’s project was anything but modest—he wanted to found the sociology of mental illness. He asked the question with a somewhat technical elegance: “Can we make room for social factors in the etiology of mental illnesses?” And of course, if so, which one?

To do this, he began by “establishing the register” of the disciplines involved in the question of mental illness. This is commendable. It is a question of avoiding confusion or even conflicts between researchers, and of guaranteeing the independence of the various human sciences and disciplines concerned: social psychiatry, which is concerned with the morbid social behavior of individuals suffering from mental disorders; the sociology of mental illness, which is interested in communities and groups—particularly those that form spontaneously or not in psychiatric hospitals; ethnopsychiatry, which establishes correlations between ethnic facts and types of illness.

We must add disciplines (“sciences” at the time, but that was “early days”) that were a bit specialized: “ecology,” which brings to sociology some of the most important aspects of the human condition, which brings to the sociology of mental illnesses the recognition of a particular spatial distribution of organic and functional psychoses (but which does not manage to grasp the causes). And industrial psychiatry, which, as its name indicates, is interested in psychopathologies linked to industrialization, and they are numerous, and sometimes serious.

The sociology of mental illness has a history whose conceptual evolution goes from Comte to Durkheim and from Freud to Sullivan and Parsons. Bastide clearly identified the two main types of theoretical approaches that divide the discipline: some that start from psychiatry and go towards sociology, others that go from sociology towards psychiatry. The sociologist reserves the right to re-establish the communication network between the three fields thus delimited, theoretically and practically.

Let us summarize the hypothesis: we cannot understand mental illness or the mentally ill if we do not take into account the society in which both are integrated. Or do not fit in. If madness can have organic causes—lesions, biochemical disorders, hereditary factors, etc.—it also has social causes, which need to be recognized and which is a matter of sociology: if an old man is vulnerable to madness, is it because he is old or because society rejects the old?

In other words, the influence of the environment must be recognized in the psychogenesis of mental illness, even its “organogenesis.” Today, this is obvious, and even a dogma. But it is still necessary to establish some foundations.

Why is this book, which is more than fifty years old, still of interest to us?

In addition to the fact that it constitutes one of the most accomplished, the densest, the most documented works of the time on questions that interest us—madness and mental health—it interests us because obviously our society presents some clinical signs of pathological features. Not to mention, of pure madness.

The Normal and the Pathological and the Family

All peoples distinguish several types of abnormality and all know what a mental disorder is.

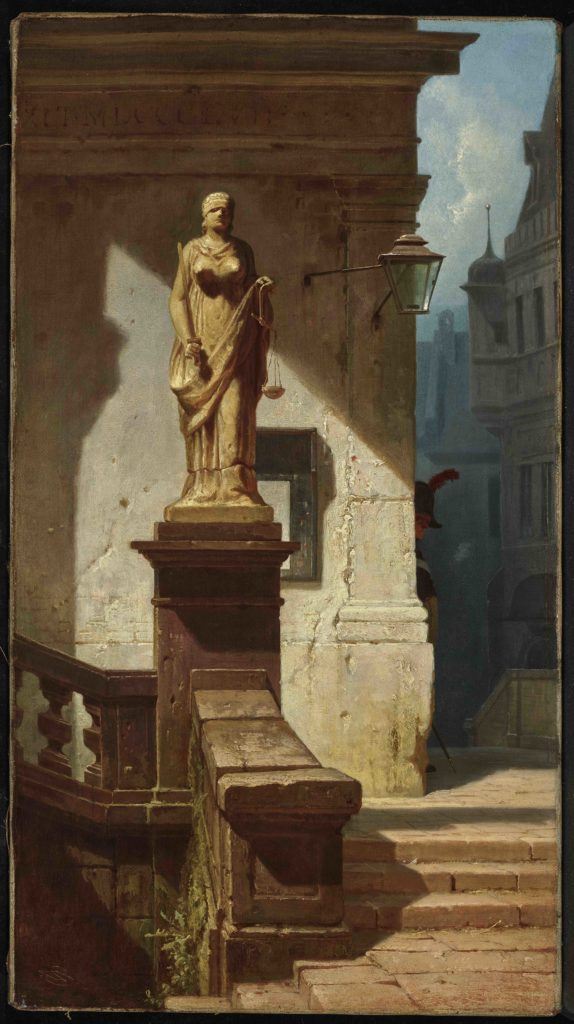

It is society that designates the sick to be treated, and it is up to the psychiatrist to find the causes and the reasons for the illness. In order to distinguish the madman from the healthy man, it is necessary to rely on an external criterion, the consensus that the healthy man meets in terms of behaviors shared with the other members of the group (the normative character of health). Hence the theorization (or paradigm) in terms of deviant behaviors or conformity behaviors—those that make social life possible (and those that can also make it impossible).

But if we admit that society comes into play in the genesis of mental illness, the question that arises is that of the more or less pathogenic character of the societies in which men are called to be born, to grow up, to fight for most often, or sometimes to integrate into when they emigrate.

It is the ethnopsychiatrist Georges Devereux who put forward the idea that there are social neuroses.

Industrial society is one that eliminates waste. The unproductive is waste: it is for this reason that the madman is designated for the social “trash,” and that, in a world dedicated to rationalization and planning, he is the only one who can make a protest heard (like that of Nietzsche or Antonin Artaud). The misfortune is that this protest cannot be heard, because it is formulated in a way that is neither intelligible nor, above all, admissible. What remains is silence; in other words, superb isolation. The mental illness is in some way the translation of this marginalism of the values rejected and repressed by society.

As isolation, or if one prefers insularity, is a general feature of our civilization, and even a real ideology, (with, on the one hand, the wild competition for the improvement of one’s social status which pushes one to seek participation, and on the other hand the cultural norms which push one to withdraw), schizophrenia appears as a perfect model of sociological category offering to men the shell that they must secrete around them to be able to maintain, on the peripheries, the systems of “blocked” values. It is indeed the “norms” and the “values” which constitute a base of references from which a system of recognition (and exclusion) is built.

It is not difficult to admit that if the individual participates in a global society and in a culture of which he is one of the “cogs,” he is more deeply influenced by the groups of which he is a part, rather than by the larger community. And the most profound influence is obviously that of the family. We all know that it is within the family that insurmountable conflicts are set up, which generate psychopathology; overcome most of the time, but not always, unfortunately.

In this respect, the family is also a “group” which has its laws, its norms, its prohibitions, its taboos; in short, a system for defining what is allowed, what is tolerated, what is admissible or inadmissible.

But there are two ways of looking at the family. From the point of view of Durkheim and most French sociologists, it is a social institution, organized and controlled by the State through civil status—or by the Church—which considers the conjugal bond as irreducible. The rupture of the marriage contract is not free; it is surrounded by guarantees; it must be formalized to become valid. From the dominant point of view of North American sociology, it is a social-group structuring, according to certain cultural norms; a set of inter-individual relationships between husband and wife, between parents and children, between brothers and sisters, possibly between the three generations. European countries are increasingly tending to open up to this perspective, which, if not exclusive of the first, can enter into competition, then into conflict and contradiction. Until today, when the anthropologically normalized and normative family institution (one man and one woman), are eroded by recent laws.

There were thus two possible psychiatries of the family, depending on whether one considers it from the institutional or relational perspective.

No need to be a great expert to announce that pathologies will multiply and undoubtedly worsen.

Religion: An Integrative Force

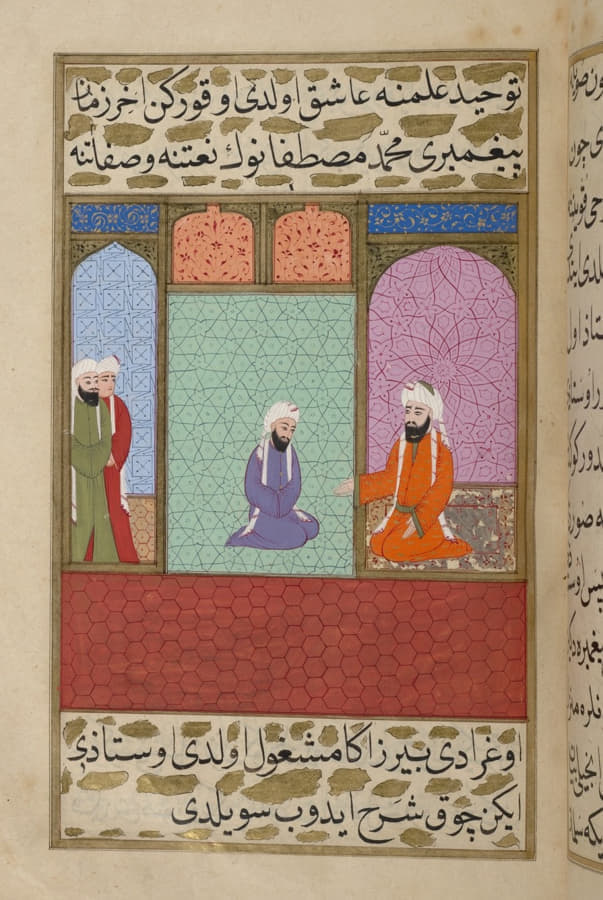

Among the sociological variables of mental illness, we also find religion, or more exactly the religious group.

If this family is Catholic, Protestant, Jewish or Hutterite, it will intervene in the constitution of a healthy psyche, but also in the structuring of psychopathologies, even neuroses or psychoses.

Bastide takes again the hypothesis of Durkheim, who conceived religion as an integrative force and who had established that suicides varied in inverse reason of the more or less integrating character of religion. But he rightly questioned the notion.

“Should we understand it as a simple statistical fact of belonging to a group whose faith one may not live, which simply marks the origin and the fact of being baptized? Or should we give this word its full meaning; that of the mystical experience lived in the depths of the soul?”

Only in the second case does religion retain an integrative function. It would have no effect on those who are not Christians and do not participate in the life of the churches. Bastide rightly points out that France has many atheists who behave in a Catholic way and who live according to the values of their ancestors: they have only secularized Christian ideals without changing their mentality.

Is it possible to establish some correlations between a certain type of mental illness and the various confessions?

Yes, answers the anthropologist, but without much theoretical significance. If the values and norms that constitute the religious culture of an ethnic group dominate in the etiology of mental illnesses, (the family factor being determined by the ethnic-religious cultural traditions, at least at the time), these variables are weighted by the “social class” variable.

Moreover, psychic conflicts resulting from religious identification are rare and in cases encountered, the interest in religious things follows the illness and does not precede it. It is not the religion that is important but the individual’s reaction to it. Clearly, it is the illness or the neurosis that is prior to the religion. “The neuroses can transform religion into a pathological construction and the psychoses into feeding the delusions. But it is not the religion which creates the one and the other.”

It would be appropriate to inform a large part of our contemporaries about this.

In the 1960s, especially in Italy, psychiatrists and members of the clergy collaborated on these difficult questions. It was a question of “saving” religious life from what could jeopardize it (intra-family conflicts, the inhumanity of industrial relations) and which could eat away at it from within and make it fail in neurosis. One sought in the community spirit or the discipline of the Churches—(Christian asceticism)—a ” dominium ” of the affective life—in particular of the impulsive life—a protective environment, an education of the spirit and an orientation towards a healthier world. Even more “holy.”

All this is still very true, in any case for the Christian religion which largely molded and configured the European culture and mentality and thus French. At least until the last forty years.

But then what about Islam in a sociology of mental illness? And what about Muslim immigration, since it is clear that it is with this specific immigration that the European peoples are confronted.

The “Culture Shock”: “The Poplar Quarrel”

A famous quarrel pitted André Gide and Maurice Barrès against each other about rootlessness. It is known as the “Poplar Quarrel” because it uses the botanical analogy. Barrès stressed the harmful effects of rootlessness; Gide saw in it the sine qua non condition of creativity—except that the two cultures between which Gide saw himself divided were those of Normandy and Neustria… There is undoubtedly a more violent duality.

What does sociology say about the question?

Everything obviously depends on the predispositions—robust personalities are enriched by this double culture. And they usually learn to exploit both of them skillfully.

In any case, there is always a crisis and this crisis for some may be difficult or impossible to overcome. Learning new cultural mechanisms is difficult after the plasticity of childhood. The new social environment is perceived as hostile, because one does not manage to master it, even if only symbolically through the shared language. More seriously, the new environment is not perceived as different but as contradictory. Anxiety and hostility are the consequences of these difficulties.

In our case, the “European” social body evolved from a Christian society, with associated values and also virtues (even in counterfeits), the morality sometimes a little narrow and puritanical—to a “secularized” society; then secular one; in other words, essentially atheist. And since a few decades, Europe became anti-Christian and even Christianophobic.

In other words, Muslims found themselves faced with a changing society, with which they had less and less affinity, to the point of no longer recognizing themselves at all in the values displayed. The new anthropological foundation only reinforced their deep aversion for a society that they perceive as perverse, immodest and deeply revolting.

Studies, fifty years ago by Georges Bastide, showed that in the case of mixed marriages, the parent belonging to a different civilization pulled the child towards his culture, which made the child internalize a double system of contradictory standards. The disorders resulted from the conflict of cultures, not from family conflicts.

It is known, for example, that the close relationship of sons to their mothers generally delays Americanization (i.e., integration). However, no one is unaware of the hold of the maternal imago in all cultures and societies, but particularly in Muslim society. It is the male child who allows the mother to finally exist. Many psychoses appear not when there is a rupture of the family or internal tribal bonds but where the abnormal rigidity of these pre-social bonds prevents the individual from freeing himself from the law of his family circle, or his restricted group remained foreign to the social community. This is exactly the situation of the Muslim family, tribal, rigid and especially more and more alien to the society that surrounds it.

In the case of a marriage between Muslim and French (of Christian tradition but most often without any knowledge of his or her religious tradition), the Muslim parent has no need to “pull” the child to him or her. The community force acts. The child will be “Islamized.”

This so-called “moderate” Islam is in reality a dormant, muted Islam. It guarantees a possible functioning in European society, according to schizoid modalities (very widespread, whatever the religion) which allow to live, to have a job. The virus is in a way “dormant.” But in the face of the mutations of our societies, and their deviated ethics, radicalized and radicalizing Islam begins to shake the whole edifice. A very deep violence comes out of it, linked to the anguish of psychological disintegration of personalities which have been structured according to modes of which we know very little. Ethnopsychiatrists have been interested in traditional cultures, but relatively little in the disorders of the Muslim population. The proof is that in 1965, Islam was not included in religious variables, nor in any variables at all.

A Psychiatry of Transplantation and Uprooting?

It is obvious that a “crisis of transplantation” is inevitable, whatever the modalities in which it takes shape.

The migration of Muslim communities is not a migration like any other. The men and women who arrive in Europe belong to a completely different civilization. The basic personality built in a Muslim society obeys rigidities and defines a mentality. The new environment can only reshape a mentality that is “compatible” with the host country, if the person does not live withdrawn in a reconstructed environment. However, it takes months before a person or a family is integrated; in other words, before they have a home, a job, a stability that is not based on parasites. The time to feed many feelings of frustration, powerlessness, envy no doubt. The perfect ground for developing mental disorders.

However, the reality that is ours is striking. “Ghettos” are not the sole responsibility of the host country, but also of the need of migrant communities to reconstitute something of their country of origin.

Even if one emigrates to improve one’s social status, the change is marked by a decline in status. We know that Germany has integrated skilled men and women with low wages and trainee status. If at first, given their situation, these doctors, computer scientists and others are happy about the “chance” they have been given, it is not certain that in the long run their appreciation does not change. However, the descent in the social scale occupies an important place in the genesis of mental disorders.

How can the old European lands, de-Christianized, and having to face attacks of a great violence that aim at destroying the anthropological base which constitutes the only common element with the Muslim community, face without risk of collapse such a terrifying aggression?

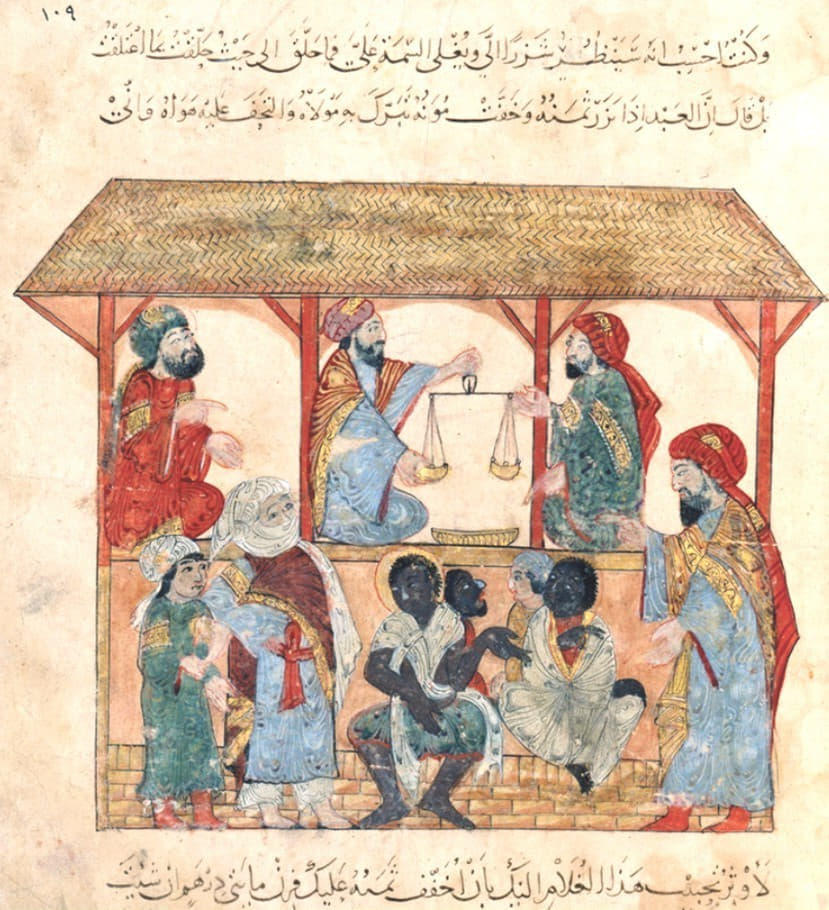

Durkheim had provided a still effective framework by distinguishing four types of solidarity: mechanical solidarity, organic solidarity, forced solidarity (which defines colonial and slave societies, and apparently ours), and finally anomie. He analyzed the phenomenon of suicide within this framework that he had elaborated. In societies with forced or anomic solidarity, there is an abnormal increase in the suicide rate. This is the case in our societies. Anomie, by developing anxiety (the ambition without brake, the amplitude of the unrealizable projects, or, today, the confusion between unrealizable dreams and projects), by multiplying the failures is particularly apt to multiply the number of suicides.

It seems to me that what we are witnessing is less a clash of civilizations than a clash—very brutal and very violent—of mentalities.

Christianity used to mediate (in an often anomalous, diffuse, sometimes rather soft way) between the Muslim community and French society. Contrary to the efforts to make people believe that we have the same God, which is not the case; but we had common or similar ethical positions in matters of sexuality, an “altruism” whose roots were undoubtedly not comparable, but which in practice are similar: almsgiving, prayer. But blinded by her internal affairs, by the post-conciliar crisis, by the preoccupation to show the world her brand new modernism, the Church remained blind to the essential.

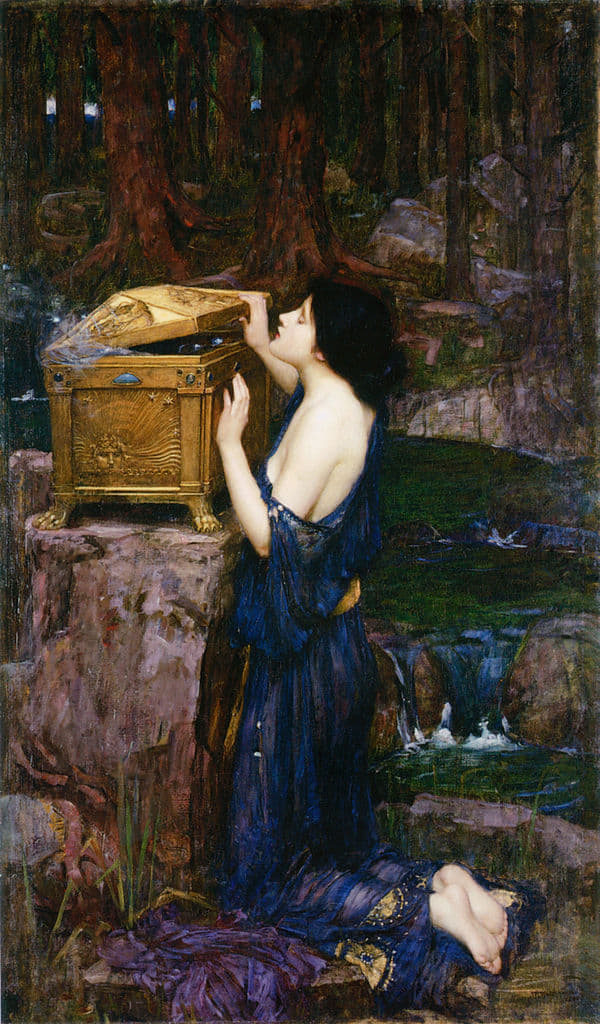

The retreat of Christianity has left Islam facing an increasingly libertine, impudent and shameless secular society, which is now seen not as different and compatible at least on the essentials, but as radically “contradictory.

And then came Muslim migration.

A Shock of Mentalities

From now on, we have to face a community, which not only does not wish to integrate itself into our society but which intends to “disintegrate” it. The madman does not invent his madness: he uses the symptomatological stereotypes that the society or the community to which he belongs provides him. He needs them to give signs. The world of madness not only feeds on images and signs borrowed from the surrounding world, but it keeps the formal laws of this world. Faced with a European madness, understood as the triumph of pure subjectivity, we have today a new pathological disorder: the “jihadist” madness, the madness of the Muslim world understood as the triumph of the religious group.

What better sign than to blow oneself up, in other words to disintegrate? The jihadist with his belt of explosives gives himself to be seen and heard by two types of audience: the Muslims, to whom he addresses himself to show the strength of his faith, and to the society he wants to destroy. And as well to his instructors.

We have two “matrices” to generate mental disorders.

On the one hand, a society suffering from dementia and suicidal madness, which no longer wants to encourage life, support old age, regulate the aggressiveness of dominant males and look after the weakest. And on the other hand, a society that pretends to freeze the roles of men and women, to control social behaviors, to fossilize effort, to forbid women any public life, to forbid them any social mobility and even any education.

They are two faces of the same unheard-of violence: convulsive fury on one side; ideological lies and mass propaganda on the other.

And between them? Ecumenical dialogue and SREM (Department of Muslim Relations) for the Churches, and for the State, ELCOs (Teaching Languages and Cultures of Origin).

In other words, nothing.

Marion Duvauchel is a historian of religions and holds a PhD in philosophy. She has published widely, and has taught in various places, including France, Morocco, Qatar, and Cambodia. She is the founder of the Pteah Barang, in Cambodia.

Featured: Pelerinage aux lieux dits saints de la ville de La Mecque en Arabie Saoudite—Le Hajj (Pilgrimage to the holy places of Mecca in Saudi Arabia—The Hajj), by Alfred Dehodencq (1822—1882); painted ca. late 19th century.