As Fernand Braudel wrote in his History of Civilizations, the large-scale commercial organization we call “the slave trade” is not a “diabolical invention of Europe,” but began in the 8th century AD with the Muslim conquest. Knowledge and appreciation of the subject is hampered by the clichés and stereotypes that surround it, as well as the lack of press coverage of even the most accessible academic works (such as Tidiane N’Diaye’s Le génocide voilé; or Jacques Heers’ Les négriers en terre d’islam. But it is also because the spirit of the times dictates that we should not upset our Muslim brothers by evoking the misdeeds of a religion that is presented to us as a hotbed of peace and tolerance. The thirteen centuries of the Eurasian slave trade resolutely belie this mythology.

The large-scale trade in men, women and children known as the “slave trade” was organized in and by the “chronological and geographical melting pot” that was Islam from the 8th to the 11th century. This traffic of shame was inaugurated in 652, when the Emir and general, Abd Allah ibn Sa’d, concluded an agreement with the Nubians, imposing the annual forced delivery of hundreds of slaves, the majority of whom were taken from the populations of Darfur.

The trade only ceased long after that: even when the caliphate disappeared and differentiated Islamic worlds emerge, not yet Muslim “nations,” if such things were even possible. It was only in the 20th century, some one hundred and fifty years after the Westerners (who took their time to put a stop to this infamy) that the Muslim world officially closed the great roads of blood, death, castration and humiliation.

In the Middle Ages, the economy of Muslim countries was based on the power demanded of slave muscles in the mines and plantations. And there was also domestic slavery: a whole middle class consumed this domesticity, which could be cut and chopped at will, as well as the women and eunuchs of the harem (tradition claims that the harem of the Caliph Abder-Rahman III in Cordoba included 3,600 women), servants, singers and musicians in the palaces of potentates and great personages.

The slave trade developed along two main axes: firstly, the trans-Saharan trade (or slave trade), which took captives from the Sudan to the Maghreb, across the Sahara; and secondly, the maritime trade, which took them from the east coast of Africa to the Orient via a variety of routes described by Maurice Lombard (L’islam dans sa première grandeur) with precise, well-documented cartography. The Oriental slave trade involved a large reservoir of people who came to be known as “the Slavs,” from which the word “slave” derives.

In France, work on the Muslim slave trade is only half a century old, and has met with much resistance. What first attracted the attention of French researchers and scholars was Sudanese gold, because all Arab authors referred to it as “the main product of black countries.” They conveniently forget the other traffic: that of human beings. Émile Félix Gautier, an ethnographer specializing in Algeria, the Sahara and Madagascar, set off the frenzy in 1935. He had sensed that the author of Hanno the Navigator’s journey (between the 5th century BC and the 1st century AD), a Carthaginian suffete, had undertaken his expedition to secure for Carthage the gold powder long known to the Lybio-Phoenicians. The introduction of the camel to the Sahara under the emperor Septimius-Severus (146-211), born in one of those Punic cities, anxious to preserve its links with Black Africa, had made it possible to conquer the desert and trade with this almost legendary Sudan. However, the Romans failed to understand the value of Carthaginian positions and trans-Saharan trade relations and traditions, which would have faded into oblivion had it not been for the fact that the Punic cities of Africa, encompassed within the orbis romanus, had maintained them through the intermediary of Berber caravan tribes.

Once Islamized, other human reservoirs would have to be found, as the Koran forbids the enslavement of Muslims (a precept that was hardly ever applied). These Berbers were to make use of the Saharan trails, restoring the ancient gold trade to its former glory and, above all, developing the trade in blacks from the Sudan and sub-Saharan Africa.

But they were not alone in the large-scale organization of this monstrous traffic. By the 8th century, the formation of the Muslim world had created an immense domain in relation to “a kind of common market” from Central Asia to the Indian Ocean, from the Sudan to the barbarian West and the region of the great Russian rivers. This ensemble was built on three previous domains: the Sassanid Empire, Byzantine Syria and Egypt, and the barbaric Western Mediterranean. This “common market” was characterized by an influx of gold, a large supply of slaves (Turks, Africans and Slavs), and a network of major trade routes stretching from China to Spain and from Black Africa to Central Asia. This network covered the whole of Eurasia, but was also subject to unstable junctions, linked in particular to conflicts between the great empire-states (such as Byzantium and Persia).

In the ancestral lands of ancient civilizations—Iran, Syria, Mesopotamia, Egypt—there was no gap between the Byzantine-Sassanid period and the Muslim era in terms of urban occupation, workshops or arts and techniques, because the economic frameworks were already in place on the eve of the Muslim conquest. The East was home to all the driving forces and dispersal centers from which the various influences associated with the new conquerors would spread westwards: Islamization, Arabization, Semitization and, above all, Iranization. It was Persia, heir through Islam to the ancient Mesopotamian home, that provided the conquerors with the mental frameworks and techniques, as well as the repertoire of ideas and artistic forms, with which to assert themselves.

But throughout the Muslim world, big business was to fall to Jewish merchants.

The first exile under Nebuchadnezzar had created a scattering and chains of Jewish communities, settled along all the major trade routes, which corresponded with the lines of Judaization. From Sassanid Mesopotamia, these religious and commercial routes reached Armenia, the Caucasus and Caspian countries, the land of the Khazars (lower Volga and Ponto-Caspian steppes), Iran, Khorasan, Khwarazm and Transoxania, and finally the Persian Gulf and India (Malabar coast). It was with these communities that, very early on in history, a class of merchants and craftsmen emerged, faithful to the trading spirit and old technical and mercantile methods of the Semitic East. In some places, these communities were more numerous and more active. But these nuclei of Judaism were not always well connected, due to the split between the barbarian (then Christian) West, the Byzantine area and the Sassanid domain. Rabbinism, which became official within the Muslim domain, welded the nuclei of Judaism, from East to West: rabbinic centralization and commercial relations, deriving from the driving forces of Abbasid Mesopotamia, went hand in hand. These relationships continued beyond the confines of the Muslim world, through links with the distant communities of Eurasia.

Until the Muslim era, Christian Syrians (Syrians and Persians above all) had been the masters of East/West trade. Their trade was also based on a chain of Nestorian and Jacobin communities. Eliminated from the maritime domain, they retained their importance in continental relations in Egypt, Syria, Mesopotamia, Iran, Armenia and Central Asia, with monasteries and places of pilgrimage playing an economic role.

At all frontiers of the Muslim world, a large part of trade was thus in the hands of the Jews and their trading houses, including the slave trade and all related activities: eunuch manufacture, slave instruction and education, currency trading and banking. The most beautiful women were channeled into the harems: abducted at a very young age, they received extensive training, particularly in music and psalmody, but not only. A few towns, including Verdun, specialized in the castration of male children and men. The fact that it was mainly carried out by Jews was due to their reputation for medical knowledge based on old Greek medicine, enriched by contributions from the Iranian and Indian schools. Nestorian “polymaths” (physicians and scholars) played a central role in the “translation sciendi” of ancient knowledge to the new Arabized world. Dual medical and philosophical knowledge (the works of Aristotle in particular) followed the same circuit. From Greece to Syria, it was translated into Syriac, Aramaic and Arabic, then transplanted to the major centers of Baghdad, Cairo and Cordoba, where Spanish Jews translated it into Latin. From there, they reached the centers of the Christian West, particularly Toledo.

The Arabian conquerors transformed this tribal Islam into a caliphal Islam: a political system of widespread domination and plunder. Not only did they seize the gold of the vanquished (treasures of the Sassanid rulers, Syrian and Egyptian churches, systematic excavations of the Pharaohs’ tombs), they also appropriated the knowledge of these ancient Aramaic-speaking sedentary civilizations, or what remained of them after the first devastating period of conquest. And it was at the junction of East and West, in the old land of Spain, that these “matrix” civilizations would cast their last fires.

Al-Andalus was not the brilliant civilization celebrated in today’s fifth-grade French history textbooks. It is the swan song of this great Christianized civilization which, having taken on Greek and Indian knowledge, transmitted it in the language of the conquerors before disappearing into the sands of the desert and history.

In the Islamized East, a few Christian communities still survive, heroically maintaining the oral structures through which faith and the Gospel have been passed down through the vicissitudes of the centuries and the continual persecutions of Islam.

Marion Duvauchel is a historian of religions and holds a PhD in philosophy. She has published widely, and has taught in various places, including France, Morocco, Qatar, and Cambodia. She is the founder of the Pteah Barang, in Cambodia.

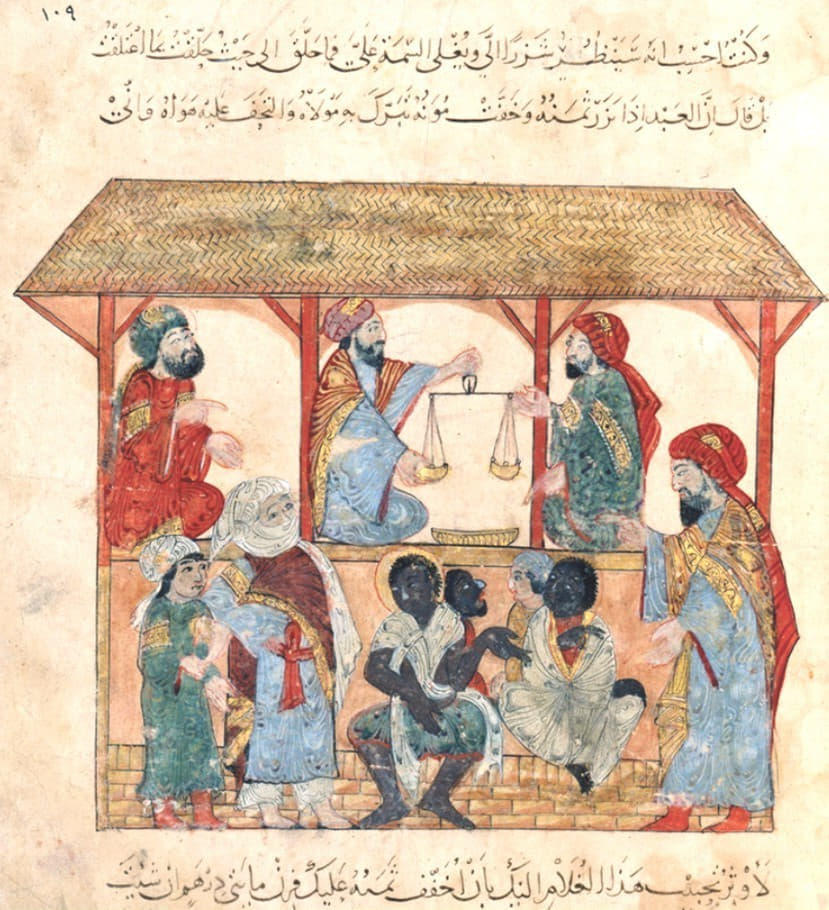

Featured: Slaves in Zabid, Yemen, folio 105, Maqama 34, by Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti, Baghdad, ca. 1236-1237.