Debates about Americanism and anti-Americanism, Americanophilia and Americanophobia, are continually rekindled as major geopolitical events unfold. To be precise, it would be more accurate to speak of love and hatred of the United States of America rather than of America, because with 10 million km2 and 332 million inhabitants, the United States is only a minor part of a continent that covers no less than 42.5 million km2 for a population of over a billion “Americans.” But ideological prejudices, linguistic conventions and semantic misappropriations being what they are, it is not easy to overcome them. Just one example: For forty years I have been protesting, without any real success, against the dubious use by French historians and journalists of the term “nationalist” instead of “national” to describe one of the two sides in the Spanish Civil War. My Hispano-American friends will therefore forgive me, at least I hope they will, for using the terms “America” and “Americans” in the conventional, partial and arbitrary senses they are given in Europe, rather than exclusively the expressions “United States” and “United Statesmen” (which are themselves problematic, since they also refer to the country and inhabitants of Estados Unidos Mexicanos).

The problem addressed in this article is that of the image of “America” and its evolution since the creation of the United States in 1776. What has been and what is the meaning given by observers of international political life to the events in which the United States has been involved since its foundation? It is worth noting at the outset that this age-old debate, which is still being rekindled, never takes the form of a clear right-left opposition. Pro- and anti-Americans have been recruited and split across the political spectrum for over a century and a half.

Many analysts have pointed out that there is, on the one hand, a structural or essentialist Americanism and anti-Americanism and, on the other, a conjunctural or circumstantial Americanism and anti-Americanism, which are limited to the praise or criticism of a given point at a given time. Among essentialist authors, we usually cite the “pro-American” French journalist Jean François Revel (who denounced his European adversaries’ “complex,” resentment” and “anti-American obsession”), or the American neoconservative Robert Kagan (theorist of the “benevolent” Empire) and, conversely, among the anti-Americans, Benjamin Barber or Noam Chomsky (who have often been denounced in the USA as traitors or masochists dominated by “self-hatred”). [See, Jean-François Revel, L’Obsession antiaméricaine, 2002. See also, Paul Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of Great Powers, 1988, and Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard, American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives, 1997].

According to essentialist authors, there is an “essence,” i.e., a positive or negative permanence, independent of history. America and Americans, according to some, struggle to spread progress, freedom, democracy, human rights and happiness throughout the world, but, according to others, they are guilty of all the errors, injustices, crimes and suffering of humanity. America and Americans thus are, for some, the beneficent friend, the disinterested defender of the oppressed, the “camp of good,” to be defended and loved, and, for others, the atavistic enemy, the incarnation of the eternal “fascist” bastard, the irredeemable nation, to be hated and slaughtered. There is thus both an essentialist xenophilia and xenophobia, which sees the Other as an immutable “essence,” sometimes admirable, sometimes detestable. The contempt, hubris and arrogance of some is always counterbalanced by the bitterness, rancor and resentment of others.

The problem is that the definition of Americanophilia or Americanophobia is very rarely fixed in the same author, and essentialist and conjunctural arguments are usually inextricably intertwined. In reality, Americanophile and Americanophobic discourses are mostly linked to historical events. Opinions hostile or favorable to the United States vary according to the era and ideological presuppositions of the actors involved, and are highly dependent on historical moments.

What are the Objective Reasons for Admiring the United States?

There are, of course, objective reasons to admire the United States of America. Admirable is the scientific and technical level of this great nation. One would have to be devoid of reason and heart to ignore it. Who would dare to claim that American literature has not reached the highest summits? Hollywood cinema, often mediocre, is certainly not as shabby as the most chauvinistic Europeans claim. Qualitatively pitiful (nearly a thousand films are produced every year), it nonetheless boasts many masterpieces. In terms of quality, 1% of American production has always rivaled the best European cinema, and for almost forty years, with the exception of a few rare cases, it has far surpassed it. Another example: the history of facts and ideas and political science. The social science or “societal” rantings of turn-of-the-20th-century American academics, fanatical followers of the “woke” ideology, cannot overshadow the admirable work of authors as diverse as Christopher Lasch, Paul Gottfried, Robert Nisbet, John Lukacs and Paul Piconne, to name but a few. All of them equal, and sometimes surpass, those of the most illustrious intellectual figures in Europe at the turn of the 21st century.

Equally admirable is the commitment of the American people to the First Amendment of their Constitution: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” Of course, one cannot ignore the ability of American jurists to reinterpret a constitutional text, sometimes in a direction absolutely contrary to the spirit of the Founding Fathers, in order to satisfy the interests of the political-economical-media oligarchy or to respond to its injunctions. Of course, we cannot be so naive as to believe that this loyalty to the Bill of Rights will endure forever without fail. But to this day, despite setbacks and repeated accusations of violations, the principle and its application stand firm. And that is no mean feat! Just compare the situation in the USA with that in France or Spain. A memorial law, which would impose the State’s official viewpoint on historical events, is still inconceivable in the United States.

All this, we must acknowledge, without being blind to the imperfections of a highly imperfect representative democracy regularly marked by elections marred by irregularities and even by soft coups d’état by the dominant oligarchy. The press in the United States is theoretically free, but in practice it is tightly controlled by the powerful and the wealthy; society is particularly unequal; the proclaimed freedom is compromised by anti-terrorism laws; the political oligarchy is partially corrupt; Mafia influences on the White House have been frequent [See, Jean-François Gayraud, La Mafia et la Maison Blanche, 2023]; untimely military interventions in the world are beyond count. All these criticisms are well known.

The Intensity of Anti-Americanism Goes Hand-in-Hand with the Intensity of Americanism

Anti-Americanism is not simply a matter of prejudice or detestation. The denunciation of the system’s dysfunctions, the distrust and fear of imperialism, are not the product of fantasy. Exceptionalism and expansionism were present from the very beginning of the American Republic. They were bound to provoke international concern, apprehension and hostility.

The foundation of any true foreign policy is the national interest. This is as true of the United States as it is of any other power. Theorizing about cosmopolitanism, globalization and multiculturalism, so fashionable among Western oligarchies, cannot mask this reality. As recent history has shown, there is no such thing as globalist “inevitability.” On the contrary, the overcoming of national interests, the phenomenon of convergence advocated and driven by Western pseudo-elites, is accompanied by new fragmentations, oppositions and reconfigurations of international relations. After all, transnational globalization is only exacerbating the desire for state sovereignty and independence, including on the “old continent.” De Gaulle rightly said that we must not make the mistake of confusing peoples, states, regimes and rulers. To ignore this is to fail to understand why virulent criticism of the United States is now the most widely shared view in the world.

Significantly, in the “Old World,” they are the defenders of the European-Atlanticist oligarchy (that of the “poodles” of Uncle Sam, Merkel, Scholz, Macron, Van der Leyen or Sánchez, all epigones of Monnet, Schuman, de Gasperi, Spaak, Hallstein, etc., themselves often accused of being nothing more than “agents of the CIA.” Walter Hallstein, first president of the European commission was, let us not forget, a former Nazi lawyer cleared by the Americans), who never wanted to see de Gaulle as anything other than an anti-American, champion of identity and national sovereignty. They never fail to blame the old General for having accepted the entry of communist ministers into his second government in 1945 when the PCF represented 26% of the electorate, but de Gaulle, critic of the “party regime,” resigned after just two months. The same people criticized the fact that de Gaulle, with Stalin’s support, had obtained a seat for France on the UN Security Council on the same footing as the victors of the Second World War. Invariably they also deplore the Phnom-Penh speech against military intervention in Vietnam (1966), the withdrawal from NATO’s integrated command to overcome bloc logic (1966) and, of course, the Montreal speech “Vive le Québec libre!” denouncing too much Anglo-Saxon influence (1967). Yet de Gaulle was not anti-American. In every serious crisis that could lead to a dreadful nuclear confrontation, the “Connétable” always honored France’s alliances against the USSR. This was the case, for example, in 1961, during the construction of the Berlin Wall (“wall of shame” for liberals and social democrats, and “wall of anti-fascist protection” for communists), or in 1962, during the Soviet missile affair in Cuba [See, Éric Branca, L’ami américain : Washington contre de Gaulle, 2017]. De Gaulle was never anti-American, even if his opponents, past and present, globalists and other Europeanists and Atlanticists, try to pass him off as a model of anti-Americanism. Clearly, for them, one cannot be a friend of America if one refuses to slavishly align oneself with the positions of the American government.

Paradoxically, it was in fact President François Mitterrand (a Socialist leader, elected President of the French Republic because of the votes of the Communists, even though in his youth he had been awarded the Francisque, the highest distinction of the Vichy regime), who had the harshest words to say about the United States. In the twilight of his last term of office, fully aware that American governments had been pursuing the definitive expulsion of France from Africa since the end of the Second World War (an expulsion completed under Emmanuel Macron with the unplanned help of Russia and China), Mitterrand confided these edifying words to journalist George-Marc Benhamou: “France does not know it, but we are at war with America. Yes, a permanent war, a vital war, an economic war, apparently a war without killings. Yes, the Americans are very tough; they are voracious. They want undivided power over the world. It is an unknown war, a permanent war, apparently without killings, and yet a war to the death” [George-Marc Benhamou, Le dernier Mitterrand, 1998. Mitterrand also said: “I am the last of the great presidents. After me, there will only be financiers and accountants.”]

[On the role of the CIA in the destruction of European states and the construction of an Atlanticist Europe, see Bruno Riondel, Cet étrange Monsieur Monnet, 2017. Former advisor to President Georges Pompidou, Marie-France Garaud, who was also a supporter of the young Jacques Chirac and an “éminence grise” of the Gaullist movement the Rassemblement pour la République (founded in 1976), said bluntly that Jean Monnet “was an American agent” (See broadcast “Ce soir ou jamais”, France 2, May 17, 2013). Disappointed by the reversals and betrayals of his protégé, Jacques Chirac, he said of him, with his usual frankness, “I thought Jacques Chirac was marble for statues, but he’s actually faience for bidets” (“Canard Enchainé,” December 2, 1985).

It is worth noting that, on the occasion of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, the Fratelli d’Italia (G. Meloni), Vox (S. Abascal), Reconquête (M. Maréchal rather than E. Zemmour) and Rassemblement National (J. Bardella rather than M. Le Pen) parties all openly distanced themselves from the neutralist, pacifist and terciferist line, opting, unambiguously, for the Euro-Atlanticist line.]

In fact, the intensity of anti-Americanism goes hand-in-hand with that of Americanism. From Monroe to Biden, via Wilson, F.D. Roosevelt, Bush, Obama and Trump, the speeches of American presidents are nourished by simple convictions: the people of the United States are “chosen and predestined;” “the destiny of the American nation is inseparable from Progress, Science, the Good of Mankind, Democracy and the Will of God.” American liberal democracy is the “best of regimes,” the “best form of modernity,” universally applicable. Articles of faith that in themselves legitimize America’s “world leadership” and planetary crusade, just as yesterday the most specious “humanist” arguments of Communist anti-capitalist propaganda camouflaged the USSR’s global expansion.

Yet these pro-American ideas and values are shared more or less consciously in Europe by virtually the entire political-economy-media oligarchy, all of whom are more or less Americanolatrous, collaborationist and servile. It cannot be repeated too often—for the latter, the history of the United States is synonymous with freedom, tolerance, prosperity, democracy and civilization. Consequently, the slightest reservation, the slightest criticism of the dysfunctions of the American system is interpreted by them as a sign of resentment, ingratitude, a spirit of decadence, or worse, an obsessive hatred of the free market and liberal democracy. In this way, the obsessive EU-NATOists condemn themselves to twisting reality to suit their ideology. As the Polish political scientist Ryszard Legutko has remarkably shown [see, Ryszard Legutko, The Demon in Democracy: Totalitarian Temptations in Free Societies, 2018], paradoxically, these “European federalists” claim to be part of a “new” liberal democracy that shares some of the most characteristic and worrying features of fallen communism [cult of “progress,” certainty of the existence of the “meaning of history,” desire to transform society by fighting against opponents of “emancipation and equality” ostensibly condemned to “the dustbin of history,” inability to tolerate contrary opinion, declared intention to create a new demos and a new man, submission of popular suffrage to unelected oligarchic bodies, dislike, sometimes verging on hatred, of the Church, religion, the nation, the family, classical metaphysics and morality, etc.]

Alongside these Americanolaters, as well as the patent detractors, there are of course the analysts, historians and political scientists who strive to circumscribe the debate on a geostrategic level. They point out that, for two centuries, North American foreign policy has oscillated between two opposing interpretations of the Monroe Doctrine (1823). On the one hand, there are those who defend the concept of a great space, the American continent, delimited and forbidden to any foreign interference, and, on the other, those who claim its antithesis, the policy of security of communication routes and the right to intervene in any space crossed by these communications. On the one hand, the supranational ideology of Pan-Americanism; on the other, the policy of interference on every continent, an instrument for the penetration of American capitalism, particularly in the markets of Asia and Europe. There are striking analogies with the Russian attitude to the Ukraine crisis. But with one major difference: Putin does not want world domination—he simply does not want to be threatened by American bases on his borders.

Similarities have often been noted, not in theory but in practice, between French republican universalism and Anglo-Saxon or American communitarian universalism. But there is a fundamental difference between the two. French republican universalism, a kind of secular, anti-Catholic counter-religion, sought to federate all members of the national community around common political and cultural values, treating them all solely as citizens. In contrast, Anglo-Saxon communitarian universalism is based on the coexistence of heterogeneous religious, ethnic and cultural groups within the same society, with mutual tolerance encouraged. The United States has historically been constructed as a collection of minority communities and cultures, with a universally accepted “founding myth” of the dominant WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) culture. But the long process that began two and a half centuries ago finally culminated in the militant separatism of the Woke.

When it comes to Americanism and anti-Americanism, perspective is everything. For Spanish-American historians and geo-politologists, the classic distinction between the two interpretations of the Monroe Doctrine, so dear to European political scientists, is not really relevant. For them, the great principles laid down by US diplomacy [Monroe Doctrine (1823), Manifest Destiny ideology (1845), Theodore Roosevelt’s Big Stick policy (1901), Franklin Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy (1932), Truman’s National Security Theory (1947), Bush’s Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) process, etc.] all lead to a single goal, all lead to the same end, summed up in these words: “America for Americans… of the North.”

Why is Anti-Americanism So Widespread Around the World?

That said, honest controversy about ideas cannot do without a reminder of the chronology of a few historical facts. In 1620, Puritan settlers, passengers on the Mayflower, landed on the North American coast. All of them were fervent Calvinists who wanted to purge Christianity of the tares of Catholicism. They defined themselves as the “new people chosen by God” to found a “new Jerusalem.” In a way, it was Calvin who landed in America with them, becoming one of the Founding Fathers of the worldview of the future United States of America. Tocqueville explains that democracy in America was born of the Protestant Reformation; that it had its origins in the English Puritan revolution, and that to a large extent the Puritans shaped the entire destiny of the United States. More recently, Huntington also recognized that the culture of the founding colonists coexisted with many other cultures, but that these were always subordinate to the dominant culture: “This culture of the founding colonists has constituted the central and most enduring component of American identity.” The “founding myth” of the Puritan settlers remains relatively solid today, although it has been increasingly reinterpreted and challenged since the 1970s, to the great danger of the American Empire.

Let us not forget that it was this same Puritan people (or at least their representatives) who, meeting in assembly, decided on and carried out the purge and ethnic cleansing of the Amerindian nations between 1637 and 1898. As Argentinian historian Marcelo Gullo rightly writes, “in the religious training of the Puritan colonists, the Old Testament prevailed over the New Testament.” In their eyes, cruelty against an Indian was “a cruelty necessary for good to prevail and for the realization of the Kingdom of God.” From the outset, the Puritan settlers knew that Indians, “the incarnation of sin and the devil,” could not be part of their “New Jerusalem.” They knew they were not there to evangelize, but to build the new Kingdom of God. Gullo explains: “To build the ‘new Jerusalem,’ the Indians had to be exterminated. There was no place for the Devil’s children in God’s Country” [see, Marcelo Gullo, Nada por lo que pedir perdón, 2022].

Nor was there any possibility of ethnic mixing with the Indians, in whom the Protestant colonists saw only men of inferior status. And this is a major difference from the conquest and evangelization of Hispanic America. “The anti-Hispanic legend in its American version,” honestly admits French Protestant historian Pierre Chaunu, “plays… the salutary role of an abscess of fixation… The alleged massacre of the Indians in the 16th century [by the Spaniards] covers the objective massacre of frontier colonization in the 19th century [by North Americans]; non-Iberian America and Northern Europe free themselves of their crimes on the other America and the other Europe.” After the iniquitous treatment inflicted on the natives by the American colonists and their rulers (massacres, treaty violations and deportations), North American Indians only existed in homeopathic doses. On the other hand, south of the Rio Grande and all the way to Argentina, the presence of large numbers of Indians and mestizos testifies to the fact that the Hispanic Empire and Catholicism were infinitely less inhumane than what is presented in the anti-Spanish Black Legend, so prized by Protestant historians.

Before the native adversary had been totally decimated after 65 conflicts (1778-1890), the United States very soon began to expand beyond its borders. Their image in the world obviously suffered enormously due to their hyper-interventionist stance. In the 19th century, between 1800 and 1898, the list of their military interventions was already impressive: Tripoli, Florida, Mexico, Argentina, Nicaragua, Japan, China, Uruguay, Panama, Fiji, Angola, Colombia, Taiwan, Korea, Hawaii, Egypt, Samoa, Haiti, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, Philippines. In 1846, they invaded the territories of Mexico. After occupying the country for two years, under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848), they wrested from it the present-day states of California, Nevada, Utah, etc. (i.e. 15% of the territory of the United States and 119% of the present-day territory of Mexico). Texas had already been taken by force from Mexico in 1836, and officially attached to the United States in 1845.

But it was undoubtedly Cuba (1898), which was the first real testing ground for their expansionist methods. Some authors even see it as the baptismal act of anti-Americanism. The daily, Le Temps, forerunner of the newspaper, Le Monde, was not mistaken, calling the Cuban operation “high filibustering” (April 11, 1898). The Cuban affair is an archetypal example of provocation, violence, cynicism and hypocrisy camouflaged behind generous motives. A textbook case, it marks the beginning of U.S. imperialism, the first international intervention or aggression in a never-ending series.

In the Luso-Hispanic world alone, the number of U.S. interventions and assaults over the last two centuries amounts to almost 70 for the major ones (and almost 800 for the minor ones). [The bibliography on the subject is considerable. Just one example is the encyclopedic work by Argentinian historian Gregorio Selser, Cronología de las intervenciones extranjeras en América Latina, 4 volumes, Mexico, CAMENA, 2010.]

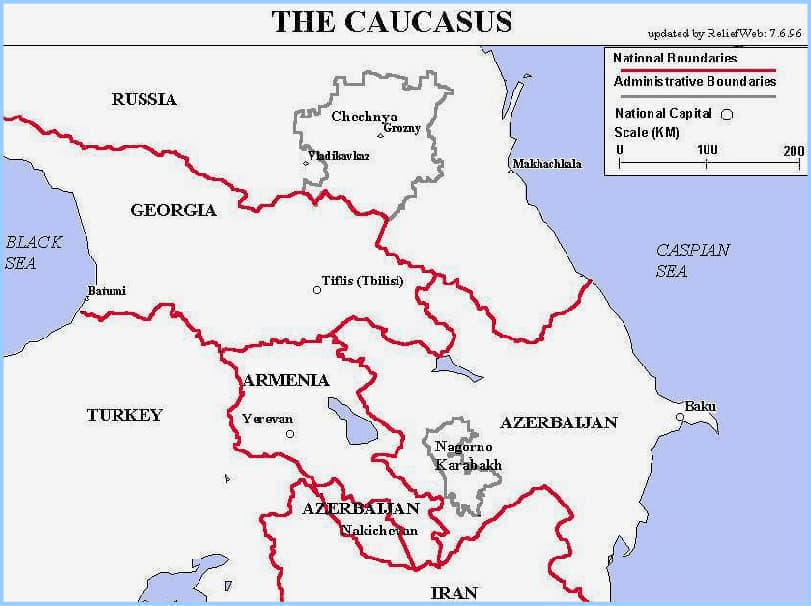

From its creation in 1776 to 2019, the United States has carried out nearly 400 military interventions, more than a quarter of which took place after the fall of the Berlin Wall [see, Sidita Kushi and Monica Toft, “Introducing the Military Intervention Project: A New Dataset on US Military Interventions, 1776–2019,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 2022]. The end of the Cold War unleashed the global ambitions of US governments. Since 1990, interventions “in the name of democracy and the defense of human rights” have multiplied (Kuwait, Iraq, Somalia, Macedonia, Haiti, Bosnia, Sudan, Yugoslavia, East Timor, Afghanistan, Philippines, Pakistan, Libya, Syria, and so on). U.S. defense spending now totals over $800 billion a year, representing almost 47% of global military spending. By way of comparison, the defense budgets of the other powers, expressed in billions of dollars, are as follows: China 278, Russia 84 (110 in 2024), India 82, Saudi Arabia 71, UK 65, Germany 53, France 44, Italy 28, Spain 27. In addition, the United States has nearly 800 military bases worldwide, while the UK has 50, Russia around ten in neighboring countries, France 6 and China just one. In February 2024, in the midst of the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, The New York Times revealed that since 2016 the CIA has financed 12 bases in Ukraine along the Russian border.

The war in Ukraine has been a terrible revelation of the incompetence and subservience of European leaders to interests that are not their own. Hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians have been sacrificed, not only to repel Russian aggression, but also to deny the European economy access to the abundant, cheap energy it needs in Russia, for the benefit of the American energy economy and its arms industries.

Few Western political, cultural or religious authorities have dared to make a frank appeal for moderation without fear of being branded traitors and Putinists by the media. Pope Francis sparked an outcry when he urged Ukrainians to “have the courage to raise the white flag and negotiate to end the war ‘before things get worse'” (“When you see that you are defeated, that things are not working, have the courage to negotiate” [Swiss television, RTS, March 9, 2024].

Arrogant, uneducated, deaf and blind, the leaders of the EU were unable to anticipate the refusal of China and India, or more broadly that of 162 states out of 195, to vote their unilateral sanctions against Russia. In two years of war, the United States and Great Britain have admirably achieved their objective: to prevent the creation of Eurasia by creating a wall of hatred between Europe and Russia. What is more, thanks to the American neocons and their European friends, the process of global de-Westernization has accelerated and now seems unstoppable. The already palpable decline of European vassal states may well be the prelude to the inevitable end of the hegemony of the “American empire.” Hats off to you! Bravo, artists!

The Collaborative Spirit of the European Oligarchy

It would be a mistake, however, to blame North America’s rulers alone for the attitude of a caste and the shortcomings of a model of society that the majority of the European oligarchy worships on a daily basis. Has not cultural identity been replaced in the hearts and minds of the “elites” of the “Old World” just as much as in those of the “elites” of the “New World” by the exaltation of GNP growth, the glorification of massive access to consumption, the desire to extend the Western way of life to the rest of the world, the mad hope that the development of the forces of production can be perpetuated everywhere indefinitely without triggering terrible catastrophes? Are not “human rights” and so-called “universal values” just as sacralized by the European ruling class? Do Europe’s vassalized and submissive “elites” or pseudo-elites not magnify the global democratic crusade on a daily basis, while at the same time scorning historical and cultural circumstances and data? Does not the narrative of Europe’s mainstream media also serve to camouflage the aspirations and material interests of the globalized caste under the guise of universal moral objectives?

To this day, the United States is the holder of global leadership. It is the superpower, the hyperpower or the Empire. In the current phase of multipolarization, of recomposition of the world’s political-economic-cultural poles, the North American thalassocratic Empire is gradually losing influence, but it nonetheless retains a hegemonic position. No emerging power is yet in a position to surpass it. The United States produces just under a quarter of the world’s wealth, but it can exploit fabulous shale gas deposits and, above all, has an overwhelming military force. Their decline is undoubtedly historically inevitable, but the fall can be slowed down for the long term.

The hubris of the American rulers, their imperial overextension and the excesses dictated by their pride, now constitute a formidable danger to the stability of the planet. Economic warfare, of which they have been a major perpetrator for decades, is a tangible planetary reality. The oil and gas war is just one of the most blatant aspects of this. To deny or ignore what is at stake—the control of the world’s energy and agri-food reserves, the domination of information, communications, civil and military intelligence—is the sign of blindness, incompetence or treason.

But intellectual honesty dictates that it must be said again and again that the American ruling class benefits from the active complicity and benevolent collaboration of the majority of the European political and economic caste. Nor should we forget to underline the role and effective action of multinational managers and major consultancies.

Let us be clear: the U.S. oligarchy, the “Deep State,” is not our only adversary. The adversary is the mortifying ideology of the globalist pseudo-elite, on both left and right; that of the leaders and apparatchiks of the main European parties in power; that of the neo-social democrats and neoliberals, so close to the Democrat and neoconservative apparatchiks on the other side of the Atlantic; that of the masters of global finance and their media affianced, jealous guardians of political correctness; that of the “organic intellectuals,” tirelessly contemptuous of sovereignty, identity and populism, which they always declare to be “demagogic.”

The cultural-political battle is not between Europe and North America, but between two cultural traditions that are tearing each other apart within modernity. One, a political minority, is that of civic humanism, the virtuous Republic and the defense of a multipolar world; the other, a majority, is that of individualist humanism, consumerist homogenization, the managerial state and global “governance,” under the dual banner of multiculturalism and neo-capitalist productivism.

Arnaud Imatz, a Basque-French political scientist and historian, holds a State Doctorate (DrE) in political science and is a correspondent-member of the Royal Academy of History (Spain), and a former international civil servant at OECD. He is a specialist in the Spanish Civil War, European populism, and the political struggles of the Right and the Left – all subjects on which he has written several books. He has also published numerous articles on the political thought of the founder and theoretician of the Falange, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, as well as the Liberal philosopher, José Ortega y Gasset, and the Catholic traditionalist, Juan Donoso Cortés. A version of this article appeared in La gaceta de la Iberosfera.

Featured: Over the Top, poster by Sidney H. Riesenberg and Ketterlinus of Philadelphia; printed in 1918.