In the framework of Washington’s policy of attempts at penetration into the Russian “near abroad,” in the first week of May, Secretary of State Antony Blinken hosted, in Washington, the Foreign Minister of Azerbaijan, Jeyhun Bayramov and the Foreign Minister of Armenia, Ararat Mirzoyan, for a series of talks. According to the final communiqué, after a series of bilateral and trilateral discussions, the parties made significant progress regarding the resolution of the conflict that has opposed Yerevan and Baku since 1991.

Moscow responded by restarting a similar initiative, taking advantage of a forum of the EAEU (EuroAsian Ecoomic Union) on May 24 and 25, marked by the presence of Azerbaijani President, Ilham Aliyev and Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, as well as that of the member states and other guests, for a bilateral and trilateral meeting (with Putin). However, the meeting, which was supposed to restart the dialogue between Yerevan and Baku (and secure the Russian grip on the region at the expense of the EU and NATO, keep out the Turks, the Iranians, the Saudis, the Chinese, the Israelis) saw a tough verbal confrontation between Aliyev and Pashinyan regarding the situation in Nagorno-Karabakh. A confrontation so hard in substance but formal in form, as to embarrass Putin himself, who presided over the meeting and who clearly showed he did not know which way to turn.

Russia is certainly worried about the crisis on its “southern front,” but it shows more and more clearly the lack of options and resources. Putin is engaged in a very difficult game, where open enemies, fragile, ambiguous, doubtful, necessary and unbearable allies and friends mix.

With so much political, economic, diplomatic, military attention and energy focused on Ukraine, Russia has reduced its attention (and capabilities) to the South Caucasus, where its grip is inexorably fraying. After a series of tensions, on April 11, a new clash between Azerbaijani and Armenian forces caused the death of four Armenian and three Azerbaijani soldiers while a massive exchange of artillery fire broke out between the two sides, despite the presence of a Russian interposition mission (with a small Turkish contingent).

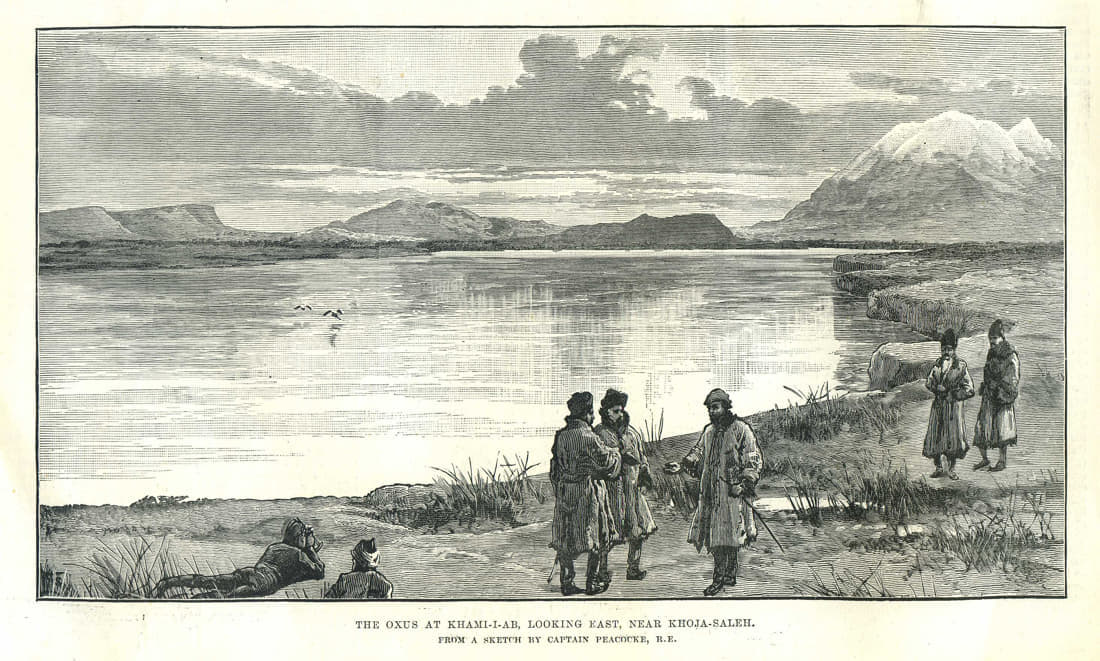

Nagorno-Karabakh, recognized as a part of Azerbaijan under international law, was occupied by the Armenian army for 26 years, following the end of the First Nagorno-Karabakh War in 1994. Under the terms of the UN Charter, Nagorno-Karabakh is Azerbaijani territory. But the province is also home to a large ethnic Armenian population who, as the Soviet Union was crumbling in 1988, unilaterally declared their independence from Azerbaijan. The first war in the 1990s ended with the victory of the separatists, supported by the Armenian regular forces and the expulsion of the few Azeris who lived in the region. The support of Yerevan allowed the separatists to enjoy a form of de facto independence, even if no country in the world, not even Armenia itself, has officially recognized them. This lack of recognition by Yerevan, which had promoted and supported it, might have seemed a paradox, but it wasn’t; in fact, Armenia wanted pure and simple union with Nagorno-Karabakh (the dream of a Wilsonian Armenia). In 1993 the UN Security Council passed four resolutions (822, 853, 874 and 884) calling for the withdrawal of Armenian troops from Azerbaijan, but Yerevan flatly ignored them.

It should be underlined that despite the enormous financial and cultural influence of the Armenian diaspora in the world, especially in the US and France, it was impossible to move the situation, legally toward unification, due to the stiff resistance of Azerbaijan. Since 2008 Baku, which has always claimed sovereignty over that territory, has begun to increase pressure on the Armenians with a series of clashes and skirmishes on the de facto border, using an ever more powerful and prepared military force; this, thanks to the enormous hydrocarbon resources, which became a real threat for the forces of Yerevan and Stephanakert.

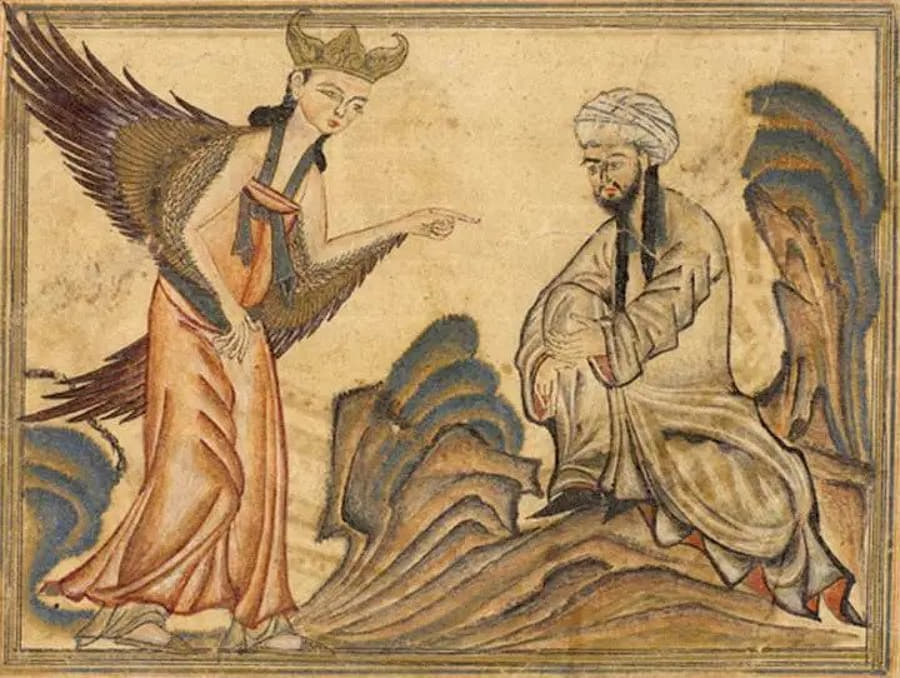

Between the end of November and the first half of November 2020, Azerbaijan, after a brief conflict, came very close to the almost total recovery of the lost territory, accompanying this with the expulsion of all the Armenian populations (Christians, while Azerbaijan is Sunni-Muslim and Turanian-speaking [Turkish lineage]) and the systematic destruction of all Christian presence in that territory. The conflict ended with a ceasefire agreement brokered by the Russians.

The ceasefire was, on the surface, meant to make room for a formal truce, but no further. This is where the Russian vision comes into play, dictated by its need to keep the South Caucasus under control, but it has few options and even fewer tools to try to impose its model. Moscow, allied with Armenia, albeit instrumentally, would prefer a freeze on the conflict and seeks to push away the option of a definitive peace treaty between the two contenders, which among other things would involve the withdrawal of the interposition forces. Despite the dire need for experienced soldiers to send into the Ukrainian cauldron, Moscow sees them as necessary to bolster her influence and a tool to keep outside any infiltration of NATO and EU in the region. Putin fears, and he saw it in 2020, that any change in the field, given that it has already happened, strengthens Azerbaijan, which seems to act more and more like a small-scale Turkey, in terms of ambitions and will to emerge (and indirectly increases the influence of Turkey, Israel and other actors).

Proof of Moscow’s will to keep the matter in the backburner was the appointment of the oligarch Ruben Vardanyan, born in Armenia and linked to the Kremlin, as prime minister of Nagorno-Karabakh (by now reduced to a patch of land flattened by Azeri bombings and garrisoned by Russian soldiers) who blocked any dialogue. Last February, Vardanyan was unexpectedly sacked from his post by the president of the breakaway republic, Arayik Harutyunyan, further showing the weakening of Russian regional influence. As proof that the South Caucasus continues to be an area of great importance to Moscow, it has appointed General Alexander Lentsov, one of Russia’s most experienced military figures (previously he served as head of the so-called center joint control, coordination and stabilization of the ceasefire in Donbas after the first conflict in Ukraine in 2014 [the Russian troops supporting Russian-speaking forces in the region], and served in Chechnya, South Ossetia and Syria)

The timing of Lentsov’s appointment was indicative: just four days before the FMs of Armenia and Azerbaijan travelled to the aforementioned meeting in Washington. Blinken and Borrell, the high representative for European foreign and security policy, would like to revive the US-EU two-track process.

The Americans are evidently aware of the benefits of reconciliation in the South Caucasus and are pressing for a solution as soon as possible. However, some signals from Brussels, such as the sending of the EUAM (EU Assistance Mission in Armenia) irked Azerbaijan, leaving the door open to sirens from Moscow, or at least allowing Baku to raise the political price for the dialogue with Brussels.

Such a peace agreement, in the pious wishes of Washington, should proceed from the recognition by Armenia that Nagorno-Karabakh is the sovereign territory of Azerbaijan, but with guarantees from Baku, which however it is absolutely not willing to grant, taking up the Turkish approach towards the Kurds. For the US, solving the issue, would allow the restart of a dialogue between the two enemies, but the path is narrow.

In fact, Pashinyan recently signalled that he was willing to do so, despite a further wave of protests, which echoed those following the defeat against Azerbaijan, of which he was accused (and objectively responsible, given that he squandered the limited military resources of Armenia in support of Nagorno-Karabakh). This, while Moscow, aiming for limited normalization between Armenia and Azerbaijan, is suggesting that the province’s status should be left off the table for the foreseeable future.

But this is a red line for Baku, which having won the war, had increased negotiating weight thanks to Western needs to sever energy ties with Russia, and replace it with the ones in Azerbaijan. Aliyev showed that it is able to raise the price and keep everyone on the ropes (also in this imitating Erdogan, for example with NATO and Swedish membership). Aliyev’s only possible concession would be an amnesty for the soldiers of the Nagorno-Karabakh forces who fought against the Azerbaijani troops, who for Baku are criminals and as such must be prosecuted. It is not much; less than what Armenia should give up, i.e., the renunciation of the achievement of national unity, but at least it is a first sign and Washington hopes for further steps.

The USA and EU seems very determined to remove Armenia and Azerbaijan from Moscow’s influence, and the two FMs met again, this time in Chisnau (Moldova) after the meeting in Washington, in preparation for the 2nd Summit of Heads of State and Government of the European Political Community, which took place on June 1st (the two had already spoken in a bilateral meeting during the 1st Summit of this architecture, promoted by President Macron, in Prague, in October 2022).

Precisely following the political-military disaster of the 2020 conflict, the government of Nagorno-Karabakh is under pressure to negotiate with Baku their reintegration into the Azerbaijani state. The issue is how to do it and what guarantees can be offered to the Armenians so that their rights as a minority group within Azerbaijan are respected, and as already mentioned, despite some small, recent openings, Baku is deaf to any hypothesis of administrative autonomy of that region, as well as cultural, linguistic and religious ones.

But having demonstrated its military superiority, nearly all the leverage in the negotiation’s rests with Azerbaijan, particularly as it knows that its position is valid under international law and has acquired interests in the eyes of potential buyers of its energy resources and for the its location as an important hub for present and future energy pipelines. Baku sees its victory in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War as a justified corrective measure that ended an illegal encroachment on its sovereignty. So, in that sense, it will be difficult to get Azerbaijan to concede much else in the negotiations.

Given the context, international actors have the difficult mission of convincing Armenia not to lose the option of a sustainable peace agreement in exchange for a very difficult option, to obtain the recognition of any autonomy for the Armenian speakers still residing in Nagorno-Karabakh, considering the military (and political) weakness of Yerevan.

In addition to dampening the danger of new violence, the EU and USA are dangling the prospect that peace could bring economic benefits to Armenia, which since the first Nagorno-Karabakh war has remained regionally isolated, with more than 80% of its land borders closed: those with the Azerbaijan to the east and those with Turkey to the west. With Georgia to the north, given the bad relations with Tbilisi, the flow of exchange is limited and difficult (the bad relations between Armenia and Georgia are historic; as soon as they achieved independence in 1919, both Tbilisi and Baku stabbed Yerevan in the back in its struggle against the resurgent Turkey that was no longer Ottoman and paved the way for the arrival of the Bolsheviks who imposed their brutal regime on the whole of the Caucasus; the continuous internal political upheavals of independent Tbilisi do not help a reconciliation with Yerevan). Armenia’s only connection to the outside world is a narrow border with Iran (a nation that has been subjected to a harsh sanctions regime for decades) through the mountainous terrain to the south and without railway lines.

Regional reintegration would open Armenia to new trade and energy supplies, eliminating its overwhelming political dependence on Russia, making it easier to connect Caspian Sea oil and gas reserves (especially for Kazakhstan, which seeks to evade an embarrassing link with Moscow).

Today Nagorno-Karabakh is in the worst possible limbo, the only area not in Azerbaijani hands is garrisoned by Russian troops and there are no prospects of reunion with Armenia, and the terms of a re-incorporation into Azerbaijan are uncertain, at least. Whether we admit it or not, the project has failed.

Given the success of field operations, Azerbaijan which has an important military apparatus, has not formally abandoned the idea of completing the recovery of control of the territories lost in the 1990s, and this keeps Yerevan close to Moscow, which still has a little more than a symbolic military contingent in Armenia, but as a guarantee against possible Turkish attacks, perhaps coinciding with a new Azeri offensive in the east.

Russia has also traditionally been the main guarantor of Armenia’s security. However, its credibility has taken a hit since 2020, when Moscow proved unable to back Armenians in the second Nagorno-Karabakh war, and showed very limited leverage vis-à-vis with Azerbaijan. Pashinyan, who showed his state of submission to Putin on the occasion of the celebrations of last May 9th in Moscow, could try to grasp the signals that the West sends out, but he has strong fears over internal stability. In fact, the elders and a large part of the large Russian-speaking minority frown upon any pro-NATO and EU oscillation (see in this light the pro-Russian riots in Georgia and Moldova), while a good part of Armenians look at prospects for socio-economic development (political life and the media are rather dynamic and free for a former Soviet republic).

But the internal Armenian scene is much more complex. Historically Armenia has an empathetic bond with Christian Russia which defended them from the Ottomans; it is strongly nationalistic. Despite the political and financial influence of the Armenian diaspora in France and the USA, Armenians suspect Western docility towards Turkish diktats (especially from Washington) and Azeri blackmail (in this case from the EU); it also has claims against Georgia and Turkey (the districts of Kars, Trabzon and Van, lost in the partition between Ankara and Moscow in the 1920s). The aforementioned debacle with Azerbaijan has exasperated Armenian public opinion; and Pashinyan himself, after barely surviving (also from the point of view of his personal safety) a very serious institutional crisis following the defeat, continues to be in a difficult situation.

Opposition parties staged massive anti-government protests at the first indications that Pashinyan might relinquish Nagorno-Karabakh claims to Azerbaijan. In early May, former Armenian president Robert Kocharian even called for Pashinyan’s resignation.

Brussels (NATO and EU) work to undermine the apparently good but weakened ties between Moscow and Yerevan by driving a wedge, given that much of Russia’s political capacity is now focused on the battlefields of eastern Ukraine. By diminishing the Kremlin’s influence in the region, Yerevan would have the leeway to build new, closer security ties with the West and attempt to boost cooperation with neighboring Georgia and Azerbaijan. But even this, in the light of the present situation and domestic, regional and international dynamics, look to be a long and painful path.

Enrico Magnani, PhD is a retired UN officer who specializes in military history, politico-military affairs, peacekeeping and stability operations. (The opinions expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations). This paper was presented at the 53rd Conference of the Consortium of the Revolutionary Era, Fort Worth, Texas, USA, 2-4 February 2023.