In his book, Sur l’Islam [On Islam], Rémi Brague gently mocks Pope Francis’ 2013 statement that “true Islam and a proper interpretation of the Koran are opposed to all violence.” “True Islam?” In this fascinating book tinged with caustic humor, striking by its erudition and its clarity, Rémi Brague puts things in their right place: by seeking to apprehend Islam under its different facets, without any positive or negative a priori, he shows that there is no “true Islam” and that it cannot exist because it does not recognize an authoritative magisterium, as it is the case in the Catholic Church. The Islamic terrorist who kills “unbelievers” can claim to be a “true Islam” just as much as the Sufi who is immersed in his meditations.

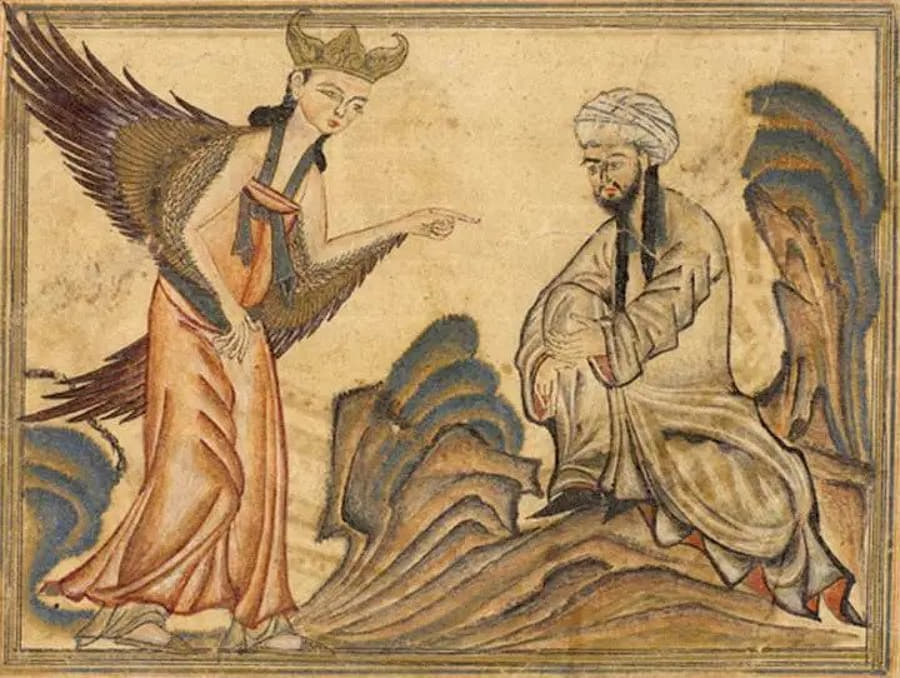

In order to understand what Islam is, therefore, what the Islamic vision of God and the world is, Brague explores its “fundamentals,” and in particular the Koran, which, since the Mu’tazilite crisis of the ninth century, has been fixed as the uncreated word of God dictated to Muhammad. This essential aspect explains an important part of the Muslim reality. The Koran contains a number of legal provisions, often extremely precise and dealing with daily life in some of its smallest details, making Islam more than a simple religion, “a legislation,” writes Brague—a “religion of the Law.” “In this way,” he continues, “when Islam, as a religion, enters Europe, it does not do so only as a religion…. It enters as a civilization that forms an organic whole and proposes well-defined rules of life.”

In Islam, reason can in no way be the source of the obligation of law, the law comes directly from God, via the Koran itself, the uncreated word of God. And when contradictions arise, they are resolved by the theory of “abrogation” which gives primacy to the most recent Koranic verse, which is always more severe than the previous one—thereby relativizing the more tolerant passages towards Jews and Christians that are usually put forward.

Thus, since there is only God’s law, the concept of natural law is meaningless and there can be, in theory, no common rules for Muslims and “unbelievers.” The consequences of this approach to law, a discipline that dominates all others in Islam, are important, notably through its repercussions on morality and the relativization of principles that we consider universal: what God wants is good; therefore what the Koran requires can only be good, including what Muhammad did, who is the “beautiful example” that God recommends to follow (Koran XXXIII, 21). Thus, murdering, torturing, conquering by the sword, lying (taqiyya), multiplying wives (including very young ones, since Muhammad consummated his marriage with Aisha when she was only 9 years old)—none of these actions are bad since they were done by the “Prophet”. Of course, no Muslim is obliged to do the same, but at least he can do so without betraying his religion.

Islam and Europe

Another theme on which Brague sets the record straight: the contribution of Islamic civilization (in which Christians, Jews, Sabians and Zoroastrians played a significant role) to Europe in the Middle Ages. Admittedly, the Arab sciences, at that time, were more developed in the Islamic than Christian sphere, but, tempers Brague, “Islam as a religion did not bring much to Europe, and only did so late,” while Western Christianity never completely ceased intellectual exchange with Byzantium, which enabled contact with Greek culture to be maintained, and which Islam in no way sought to assimilate.

For about five centuries, Islam, as it were, interrupted its cultural development and gradually allowed itself to be overtaken and dominated by Europe, causing intense humiliation among many Muslims—this is what Brague calls the “ankylosis” of Islam. Today, if it were not for the manna of oil, the Muslim countries, scientifically and militarily weak, would have no bearing at the international level. Their asset is nevertheless their strong demography, coupled with massive immigration to Europe, which has allowed the installation of vast Muslim communities, financed by the money of black gold. This is another, more patient but undoubtedly more effective way to win and thus take revenge on the past. When will we realize it?

Christophe Geffroy publishes the journal La Nef, through whose kind courtesy we are publishing this article.