“He who knows how to wage war conquers another’s army without fighting; takes another’s fortresses without laying siege; crushes another’s state without keeping his army out long,” says the famous ancient Chinese treatise The Art of War, whose authorship is traditionally attributed to the military commander and strategist Sun Tzu (6th-5th centuries B.C.).

Surprisingly, this statement is still very relevant. Moreover, Sun Tzu can be called one of the first theorists in the field of hybrid warfare, which seems to be a modern phenomenon. The treatise of the ancient Chinese philosopher still serves as the basis for theoretical approaches in the activities of the intelligence services of many countries, including the United States.

Speaking of the role of the United States in the formation of the concept of hybrid warfare, it is worth noting that this country was the first to develop and apply the term. Over time, the American (and generally Western) concept of hybrid warfare has been constantly changing, causing a lot of controversy among many researchers and analysts studying hybrid warfare. One such analyst is Leonid V. Savin, who in his book Hybrid War and the Gray Zone examines in detail the genesis of the concept of hybrid warfare, the scholarly developments of Western authors and the further transformation of the term. From the title of the book, it is easy to understand that in addition to hybrid warfare, the work examines another no less remarkable phenomenon, namely, the “gray zone. Thus, in his book Savin examines in detail the evolution of the Western concept of hybrid warfare and the gray zone, and analyzes the changes that have occurred in the approaches to the study of these phenomena in the context of the changing geopolitical picture of the world.

Before turning to the content of the book, I would like to say a few words about the author. Savin is a political scientist, the author of many books on geopolitics and contemporary conflicts, including such works as Towards Geopolitics, Network-centric and Network Warfare: An Introduction to the Concept, Ethnopsychology: Peoples and Geopolitical Thinking, New Ways of Warfare: How America Builds its Empire, and many others. He is the editor-in-chief of the information and analytical portal Geopolitika.ru, following the Eurasian approach. In this regard, even before reading the book, one might assume that Savin in his work will speak in the spirit of Eurasianism, criticizing the unipolar globalist model of the world, promoted by the United States. As it turns out, these assumptions are not mistaken.

Hybrid War and the Gray Zone consists of three parts, which, in turn, are divided into smaller sections. However, before proceeding directly to the consideration of the concepts of “hybrid warfare” and “gray zone,” L.V. Savin highlights some of the changes that have occurred in modern conflicts in recent years. In addition, the author discusses new trends in international relations, in the context of the current geopolitical reality. According to the political scientist, in our complex and contradictory world, the problems of new forms of conflicts should be approached as objectively and cautiously as possible, because a common understanding of any modern problem is not so easy to find.

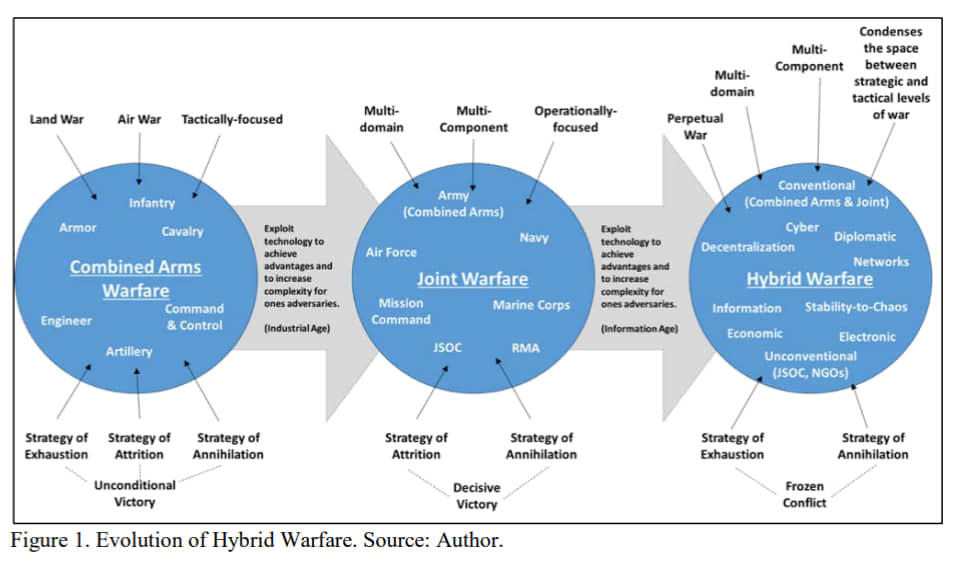

The first part of the book is devoted to the evolution of the term “hybrid warfare,” from its first mention in 1998 to the present day. Savin examines various interpretations of the concept developed by the Western military-scientific community. Thus, the author studies and analyzes the works of R. Walker, J. Pinder, B. Nemeth, J. Mattis and F. Hoffman, C. Gray, M. Booth, J. McQueen, N. Freyer R.W. Glenn, B. Fleming, as well as US doctrinal documents on hybrid warfare, including the US understanding of Hybrid Warfare (2010), Guide to Organizing a Force Structure to Counter Hybrid Threats (2015), the Military Strategy Analysis of the US (2015), TRADOC G-2, Joint Operating Environment 2035, and the Joint Force in a Contested and Disordered World (2016). In addition, Savin examines the approaches of NATO and the EU, which have developed their own concept of hybrid warfare.

It is worth noting that a separate place in all theoretical developments of Western countries on the problems of hybrid warfare is given to Russia. The author of the book devotes a separate chapter to this phenomenon. In particular, Savin describes in detail the approach of U.S. Army Major Amos Fox, who assesses Russia’s actions in the context of hybrid warfare.

After reading this chapter, it is clear why the term “hybrid warfare” is so difficult to understand. The answer is simple: there is no single definition of “hybrid warfare” because, first, each researcher interprets the concept differently, and second, it is constantly changing and evolving depending on the geopolitical context.

In addition, the term is very ambiguous and is interpreted by all sides in their own interests. As for Western interpretations of the concept of hybrid warfare, most of them state that hybrid warfare is waged primarily by Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran. Obviously, labeling these countries as “hybrid actors” is largely meaningless, since there are hardly any countries (much less major powers) that are not currently engaged in hybrid warfare. Hybrid warfare is the new reality (is it new?) in which modern society exists. Moreover, the label of “hybrid actor” is itself part of the hybrid warfare waged by Western countries, among others.

The second part of the book, as one might guess, is devoted to the study of another concept—the “gray zone.” This part again begins with how Russia is labeled. This time Savin cites the example of a statement by Brian Clark of the Hudson Institute, who noted that “Russia is waging an aggressive war in the gray zone against Japan.” Thus, the author begins the topic for a new discussion—about the interpretations of the concept of the “gray zone.”

The second part also examines the evolution of the concept, giving interpretations by the U.S. State Department and Congress, as well as by major think-tanks such as RAND and CSIS. It is worth noting that many approaches are accompanied by illustrations in the form of diagrams, which makes it much easier to understand one or another interpretation of the “gray zone” concept. Savin considers two interpretations of the “gray zone”—as a disputed geographical area, and as an instrument of political struggle. The author presents the cases of China, which has disputed territories in the South China Sea, and Israel with its long-standing activity in the gray zone.

The concept of the “gray zone” is no less ambiguous than the previously considered concept. As in the case of hybrid war, Savin also believes that the “gray zone” in the coming years will serve as a special label for any actions of certain states, primarily Russia, China, Iran and North Korea. After reading this section, one can draw a conclusion similar to the one given earlier on hybrid warfare; and this is no accident: the concepts of “hybrid war” and “gray zone” are indeed very similar and interchangeable in many ways; it is not immediately clear what their difference is, and whether there is one at all. This is what the author devotes the third part of the book to.

Thus, in the third part, the political scientist combines the two concepts under study by analyzing various documents and studies in which “gray zone” and “hybrid warfare” act as synonyms. This part of the book definitively answers the question of whether a war can still be fought without direct combat operations. In addition, the last case study examined by the author, the Russian special operation in Ukraine, once again proves that the actors of hybrid warfare and actions in the “gray zones” are not only Russia, China, Iran and North Korea, but also the “collective” West. New instruments and methods of confrontation are indeed regularly introduced and tested in hot spots by different countries, including both Russia and NATO member states and other international actors.

As for the differences between the two terms, they are indeed difficult to define, and the third part of the book confirms this. As many of the studies examined by Savin show, mixing the concept of “gray zone” and “hybrid warfare” is indeed possible. This phenomenon is most clearly explained by Arsalan Bilal, a member of the Arctic University research group: “The hybrid war itself can take place in the gray zone, and the gray zone, respectively, creates conditions for the hybrid war.”

In summarizing, Savin repeats the thesis that the West will continue to label Russia a “hybrid actor” and accuse it of malicious actions in the gray zone, using political rhetoric and fabricated data to do so. In addition, Savin explains why it is important and necessary to study Western approaches and experience in hybrid warfare.

Speaking about the overall impression of the book, we can say without a doubt that it greatly adds to the body of knowledge on the topic of hybrid warfare, which is currently more relevant than ever. The book will be especially useful for those readers who study new forms of conflicts—information confrontation, cyber warfare, economic wars, etc.

It is also worth noting some nuances. First, despite the small size of the book, one cannot say that it is easy to read. It contains a lot of complex terminology, which is not suitable for the unprepared reader. But we should not forget that this work is intended for a specialist audience—researchers and theorists in the field of conflictology, international relations and military strategy; people who make political decisions and are engaged in the development of information content. In effect, to read this monograph, one must have a certain knowledge base, at least in the field of international relations.

Second, for the most part, the work describes Western research on the topic at hand. Although the author’s point of view and sentiment can be felt “between the lines” while reading the book, I would have liked to see more commentary and explicit discussion by Savin in the work. This would have helped to delve even deeper into the topic of hybrid wars and “gray zones,” as well as to better understand what Western experts are trying to convey to the readers of their works. An expert’s comments are never superfluous.

After reading this book, two important conclusions can be drawn. First, hybrid wars are a reality in which we will always have to exist. We ourselves are part of hybrid warfare; and, in many ways, we are its object. In the age of information society and technology, there is no other way—we have become part of this geopolitical reality whenever we access social networks, read the news, turn on the television, etc. We are all objects of pervasive influence, objects of an endless flow of information that serves the interests of one side or another of the hybrid warfare. The second conclusion, which follows from the first, is the need to be able to perceive critically any information. Even if the source is authoritative (and the sources given in the monograph are very authoritative), all of them also serve someone’s interests and are always biased, as Savin’s book readily proves.

Anastasia Tolokonina is a graduate student, Department of Journalism Theory and History, at the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia. [This review comes to us at the kind courtesy of Geopolitika.]

Featured: “Die Schachpartie” (The Chess Game), by Lucas van Leyden; painted ca. 1508.