Representatives of the Western community are quite comfortable rallying around NATO narratives about the causes of the armed conflict in Ukraine and not placing themselves in the discomfort of doubting and testing the postulates that dominate public opinion.

However, getting out of this intellectual comfort zone—which, in fact, psychologically, is just a zone of fear—is an important exercise for all those who advocate the search for truth, which can often differ significantly from the narratives established by the protagonists of the dominant issues.

In this analysis, I will not go into all of the historical elements of each of the conflicting parties that are clearly important and that have led to the confrontation in which the world finds itself today, but I wish to illuminate the really dominant role, dissimulated from the naked eye, of the key player in this conflict: the United States of America.

History shows us that, despite appearances, no war of the past has ever had a single cause for its outbreak.

At the heart of every major conflict is certainly a blueprint of multiple causes and sub-goals to be achieved in the framework of a major ultimate goal, often far beyond the war itself.

The trigger causes declared by the conflicting parties are merely a reflection of the culmination, the tip of an iceberg of deep disagreements that not only can no longer be resolved diplomatically, but often, on the contrary—whose diplomatic resolution would be an obstacle to the achievement of predetermined and carefully concealed objectives.

Establishing Democracies

Basically, the United States of America and, secondarily, the rest of the Western community, claim that the cause of armed conflicts in the world initiated by the latter is the establishment of regimes of legal states, of individual, collective freedoms and as lights of democracy in regions that are the home of tyranny, dictatorship and barbarism.

However, when we analyze the totality of the more than fifty wars and armed interventions since the end of World War II, directly by the armed fist of the United States and/or indirectly through satellite countries, and then analyze the final outcome of each of the combat encounters, we can make one significant observation:

• Either the United States of America is incredibly bad at achieving its predetermined goals—as the latter are never achieved;

• or, and to be more serious, the true causes of the continuous process of destruction of parts of the world are not quite, or, to be more precise, have nothing to do with the advertised goals.

The objectivity of this observation cannot be doubted, for there are too many precedents of “implementations” whose end results are well known to us. To mention just the biggest ones, we can mention the wars in Korea and China, in Guatemala, in Vietnam and Cambodia, in Iraq, in Bosnia and Serbia, in Afghanistan, in Libya and in Syria.

Not to mention America’s many “secondary” interventions throughout modern history, including direct bombings of civilians, such as in Cuba, Congo, Laos, Grenada, Lebanon, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Iran, Panama, Kuwait, Somalia, Sudan, Yemen and Pakistan.

And even this list is by no means exhaustive, since it does not account for so many confidential operations conducted around the world to establish “democratic values and human rights.”

The statement of the general condition acquired by “liberated” societies, their quality of life before and after the processes of “democratization” passed, can only cause great bewilderment to the observer.

Survival of the United States of America

Without disregarding the fact that the American people are, in themselves, quite sympathetic and friendly—a fact no one who has had experience of intercourse and interpersonal relations with their representatives can deny, including myself, who has had the honor of knowing a number of Americans who are bearers of high human values and for whom I have friendship and deep respect—the fact cannot also however be denied that the freedom of thought of the American people, in its overwhelming majority, is directly controlled by the American “deep state” and its lobbyists,

The noble motives of the United States’ armed interventions in the world presented to the American population differ little from those advertised in the international arena.

Contrary to the narratives displayed by some U.S. antagonists, for the American “deep state” the true reasons for the repeated large-scale massacres—it is difficult to call them modus operandi otherwise—do not have as their fundamental ultimate goal world domination, per se, for domination’s sake.

This qualification is not entirely accurate. The ultimate goal is far more pragmatic: the survival of the United States of America.

Not just survival as a state entity, but the survival of the structures that enable the realization of super-profits for the elites, on the one hand, and, on the other, the survival of the model and standard of living acquired by the country with the end of the Great Depression, which ended with the beginning of World War II and the revival of the American economy through the military industry.

This survival is simply impossible without military-economic, or more precisely, military-financial world domination.

It is no historical coincidence that the military budget, called “defense budget,” of the United States alone exceeds one-third of world defense spending, a crucial element in maintaining financial dominance on a global scale.

The concept of survival at the expense of world domination was clearly articulated at the end of the Cold War by Paul Wolfowitz, the US Under Secretary of Defense, in his so-called Wolfowitz Doctrine, which viewed the United States as the only remaining superpower in the world and whose main goal was to maintain that status: “to prevent the reappearance of a new rival either in the former Soviet Union or elsewhere that would be a threat to the order previously represented by the Soviet Union.”

The Main Underlying Reasons of the Conflict in Ukraine

Leaving aside the lofty narratives appealing to the psychological sensitivity of the Western masses, who must fulfill their prescribed role of approval, let us look at the real causes, the underlying pillars of the new confrontation in the general framework of the survival of the United States of America: the conflict in Ukraine.

These underlying, interdependent pillars are three in number:

• Maintaining the global dominance of the U.S. financial system,

• weakening the economy of the European Union through the maximum destruction of relations between Russia and the EU

• and a significant weakening of Russia’s position in the framework of the future conflict with China.

All other elements of the current conflict in Ukraine, from the American side, such as the lobbying of the American military industry, the conquest of new energy markets, the protection of significant American economic assets on Ukrainian territory, corruption schemes, personal revanchism of Russophobic American elites, those from Eastern European immigration and many others—seem to me only as additions, derivatives and consequences of the three listed main reasons.

The first of the three underlying pillars of the conflict in Ukraine: maintaining the global dominance of the U.S. financial system.

The global dominance of the US financial system is based on a number of elements, chief among them the extraterritoriality of US law, US treasury bonds, and the petrodollar.

It is absolutely impossible to know or understand the true reasons, not only for the events in Ukraine, but also for almost all wars initiated directly by the United States of America, without an accurate vision of the aforementioned elements. So, let us look at them in detail.

The Dollar and the Extraterritoriality of American Law as a Weapon of Economic Warfare

The concept of extraterritoriality of American law is the application of American law outside the borders of the United States, allowing American judges to litigate facts occurring anywhere in the world.

The main element used as a pretext for prosecution is the fact that U.S. national currency is used in transactions.

Thus, the legal mechanisms of the extraterritoriality of U.S. law provide U.S. companies with a serious competitive advantage. Totally illegal from the point of view of international commercial law, but quite legal from the point of view of U.S. law.

How does it work?

Extraterritoriality of U.S. laws requires foreign companies using the U.S. dollar in their operations to comply with U.S. standards and submit to the supervision and control of the U.S. government, which makes it possible for the latter to legitimize economic and industrial espionage and implementation of actions aimed at preventing the development of competitors to American companies.

The incriminated foreign companies will be prosecuted by the U.S. Department of Justice and must “regularize” their situation by assuming surveillance for several consecutive years under a “compliance program.”

In order to establish their world domination, countless lawsuits are launched without any substantive justification, the real purpose of which is access to competitors’ confidential information and economic interference.

Moreover, by artificially exposing foreign companies, of interest to U.S. groups, to the risk of paying large fines in favor of the United States, U.S. justice puts the victims in a position where the latter are not inclined to show hostility to the idea of being taken over by American companies, in order to avoid serious financial losses.

U.S. Treasury Bonds and Petrodollars

There is such a term in accounting as bad debt.

U.S. Treasury bills are bonds that are bought and redeemed in U.S. dollars and are essentially bad debt. Why?

Today, the U.S. sovereign debt has exceeded $31 trillion and continues to grow by several billion dollars daily. This figure far exceeds the annual GDP of the United States and turns the bulk of the securities issued by the U.S. Treasury into more than questionable values, since the latter are to be repaid in national currency. A currency whose issuance is not, for the most part, backed by any real assets.

The solvency of U.S. Treasury bonds is guaranteed solely by the printing of money and the trust in the U.S. dollar, which is based not on its real value, but on the military world domination of the United States.

What does this have to do with Russia?

Since Vladimir Putin came to power, the Russian Federation has been progressively getting rid of U.S. treasury bonds. Since 2014, the beginning of the conflict provoked by the U.S. in Ukraine through a coup d’état, Russia has gotten rid of almost all U.S. debt. Whereas in 2010. Russia was one of the top 10 holders of U.S. Treasury bonds, with more than $176 billion, in 2015 it held only about $90 billion, meaning that the total mass of these assets has almost halved in 5 years. Today, Russia holds only about two billion U.S. debt, an extremely insignificant amount, comparable to the mathematical error of the global Treasury bond market.

In tandem with the Russian Federation, the People’s Republic of China is also progressively getting rid of this dangerous debtor. Whereas in 2015 it held more than $1,270 billion in U.S. bonds, today that amount is below $970 billion, a decline of ¼ in 7 years. Today, the amount of U.S. government debt held by China is at its 12-year low.

Along with getting rid of U.S. Treasuries, the Russian Federation has initiated a gradual process of freeing the world from the petrodollar system.

A vicious spiral has been set in motion: the loosening of the petrodollar system will deal a significant blow to the U.S. Treasury bond market. Falling demand for the U.S. dollar in the international arena will automatically cause a devaluation of the currency and, de facto, a fall in demand for Washington treasury bills, which will mechanically increase the interest rate on the latter, making it impossible to finance the U.S. public debt at current levels.

Critics of the postulate that a falling dollar against many currencies would be very damaging to the U.S. economy argue that a weaker dollar would lead to a significant increase in U.S. exports and thus benefit U.S. manufacturers, which would in fact reduce the U.S. trade deficit.

If they are absolutely right about the beneficial effects of dollar devaluation on U.S. exports, they are radically wrong about the inevitably destructive ultimate impact of the process on the American economy, because their position ignores a fundamental element: the United States is a country that has been on a deindustrialization path for decades, and the positive impact on exports will be relatively minor in the face of a giant trade deficit. A deficit that has already reached record levels in U.S. history in 2021 and with the devaluation of the dollar, and hence higher import costs at all levels, will have an absolutely disruptive effect.

Thus, “settling scores” with the two culprits of the current situation—Russia and China—is a key element of the survival strategy of the United States.

Petrodollars

With the collapse in 1971 of the Bretton Woods agreements in force since 1944, the global dependence on the U.S. dollar began a very dangerous decline for the U.S. economy, and the latter had to look for an alternative way to increase global demand for its national currency.

The way was found. In 1979, the “petrodollar” was born in the framework of the U.S.-Saudi agreement on economic cooperation: “oil for dollars.” Under this agreement, Saudi Arabia committed itself to selling its oil to the rest of the world only in U.S. dollars, and to reinvesting its excess U.S. currency reserves in U.S. Treasury bonds and in U.S. companies.

In return, the U.S. made commitments and guarantees of military security to Saudi Arabia.

Subsequently, the “oil for dollars” agreement was extended to other OPEC countries, without any compensation from the Americans, and led to an exponential dollar issue. Progressively, the dollar became the main trading currency and other raw materials, giving the latter a place as the world’s reserve currency and giving the United States unparalleled superiority and enormous privileges.

Today we are witnessing a strategic rupture in relations between the United States and Saudi Arabia, which is due to several major factors, among which are a very significant reduction in America’s imports of crude oil, of which Arabia was the largest supplier; the end of American support for Saudi Arabia’s war against Yemen; and the intention of US President Joe Biden to save the nuclear agreement with the Shia mullahs of Iran, the sworn enemies of the Sunni Saudis.

This triple “betrayal” by the Americans was taken extremely hard by the Saudi Kingdom, which is particularly sensitive to issues of honor in bilateral relations. The strategic differences between the two countries reached a climax with the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, when the Saudi authorities were faced with an existential choice: to continue moving in the footsteps of the United States, or to join the camp of the main adversaries of the USA, which are China and Russia. The second option was chosen.

Unlike America, which has neglected the Saudis’ strategic interests, China has, on the contrary, increased its cooperation with Saudi Arabia. And this bilateral relationship is not limited to the fossil fuel sector, but is expanding significantly in infrastructure, trade and investment. Not only is major Chinese investment in Arabia steadily increasing and China is now buying up nearly a quarter of the Kingdom’s global oil exports, but the Kingdom’s Sovereign Wealth Fund is also planning to begin significant investments in Chinese companies in strategic sectors.

In parallel, in August 2021, a military cooperation agreement was signed between the Saudi Kingdom and the Russian Federation.

Like Russia, Saudi Arabia has taken the path of de-dollarization of trade, and investment with China.

The joint and synchronized actions of Russia, China and OPEC countries on the path of progressive de-dollarization gained momentum with the beginning of the conflict in Ukraine, which tore the masks off, and will have an almost inevitable avalanche effect against the global dominance of the U.S. financial system in the future, as central banks in many countries are invited to rethink the logic of reserve accumulation as well as the merits of investing in U.S. treasury bonds.

A Declaration of War on the U.S. Dollar

The military action in Ukraine against Russia and the impending war in the Asia-Pacific region against China are nothing but part of the U.S. reaction, viewing the actions of Russia and China against the global dominance of the U.S. currency as a real declaration of war.

And the United States is quite right to take this declaration more than seriously, for the massive separation from U.S. Treasuries, coupled with the progressive shifting of the petrodollar system by powers like Russia and China, is nothing short of the beginning of the end of the American economy as we have known it since the end of World War II—and the beginning of the end of the United States as we know it today.

The nations that have in the past dared to threaten the global dominance of the U.S. monetary system have paid dearly for their audacity.

The difficulty is that the Russian Federation, like the People’s Republic of China, are military powers that cannot be attacked directly under any circumstances-which would be tantamount to suicide. Only “proxy” and hybrid wars can take place against these two countries.

Today we are in the “Russian phase.” Tomorrow we will be in the “Chinese phase” of the confrontation.

It is important to note that the events in Ukraine are by no means the first, but the third great American Dollar War, not to mention the two “Cold” Dollar Wars.

What were these wars other than the one we know today?

They were the war in Iraq and the war in Libya. And the two “Cold” Dollar Wars were the wars against Iran and against Venezuela.

The First Great Dollar War

Speaking of the First Dollar War, that is, the war in Iraq, one must put aside the famous vial of imaginary anthrax that U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell shook at the UN on February 5, 2003, to destroy the country and massacre the Iraqi people—and instead recall the facts. Facts far removed from American imagination.

In October 2000, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein made a statement that he was no longer willing to sell his oil for U.S. dollars, and that further sales of the country’s energy supplies would be made only in euros.

Such a statement was tantamount to signing the president’s death warrant.

According to an extensive study by the American Civil Liberties Union and the Foundation for American Journalistic Independence, between 2001 and 2003 the U.S. government made 935 false statements about Iraq, 260 of which were made directly to George W. Bush. And of the 260 knowingly false statements made by the U.S. president, 232 related to the presence of non-existent weapons of mass destruction in Iraq.

Colin Powell’s vial, after the latter’s 254 false statements on the same subject, was only the culmination of a long and painstaking preparation of national and international public opinion for the imminent extermination of the Iraqi threat posed to American currency.

And when in February 2003, Saddam Hussein carried out his “threat” by selling more than 3 billion barrels of crude oil worth 26 billion euros—a month later, the U.S. invasion and total destruction of Iraq, the tragic consequences of which, with the destruction of all infrastructure of the country and the enormous number of civilians killed, are well known. To this day, U.S. authorities strongly argue that the war had absolutely nothing to do with Iraq’s desire to free itself from the petrodollar system.

Given the total judicial impunity for crimes against humanity committed by successive United States governments, the latter have not even bothered to cover them up with stories that deserve the slightest credibility in the eyes of the international community.

The facts are well known, and we could have stopped there. But to make the process of “protecting” American interests even clearer, including the current events in Ukraine, let us also talk about the penultimate—the Second Great Dollar War—the war in Libya.

The Second Great Dollar War

Six years after the Iraqi threat was eliminated, a new existential threat to the U.S. dollar emerged in the person of someone who refused to learn the lesson of Saddam Hussein’s tragic fate: Muammar Gaddafi.

In 2009, as president of the African Union, Muammar Gaddafi proposed to the states of the African continent a real monetary revolution that had every chance of changing the fate of the continent and was therefore met with great enthusiasm—to escape the domination of the U.S. dollar by creating an African currency union in which oil and other African natural resources exports would be paid for mainly in gold dinar, a new currency to be created that would be based on gold reserves and financial assets.

Following the example of OPEC Arab countries, which have their own sovereign oil funds, African oil-producing countries, starting with oil and gas giants Angola and Nigeria, launched processes to create their own national funds from oil export revenues. A total of 28 African oil and gas producing countries took part in the project.

Gaddafi, however, made a strategic miscalculation that not only “buried” the gold dinar, but also cost him his life.

He underestimated the fact that, on the one hand, for the American state, and on the other hand, for the “deep state” of Wall Street and the City of London, it was completely out of the question that this project could be realized.

Because not only would it put the U.S. currency in existential peril, but, moreover, it would deprive the banks of New York and the City of London of their habitual rolling of trillions of dollars coming from the African continent’s commodity exports. The United Kingdom was thus in complete symbiosis with the United States in its desire to destroy the power that threatened its well-being.

Once the “allies” decided to neutralize the new threat, they did not care much about the strange temporal coincidence in the eyes of observers—more than 40 years of inaction against Gaddafi, who came to power in 1969 and as soon as he presented to the African Union the project of financial revolution, a new civil war broke out in Libya.

With the criminal invasion and destruction of Iraq based on the crude and deliberate lies spread at the UN in 2003 by the American state through Colin Powell about the so-called weapons of mass destruction allegedly possessed by Saddam Hussein, the United States was not willing to repeat the same pattern and had to diversify the invasion so as not to expose itself as a war criminal in too obvious a perspective.

At the moment when the new “Arab Spring” in Libya reached the brink of its complete suppression by the forces of the Libyan state, the Americans, remaining in the shadows, used the satellites and vassals—France, Britain and Lebanon—to wrest from oblivion the UN Security Council resolution against Libya of 1973—over 35 years old—to attack and destroy the country.

And this project itself was carried out in violation of even the UN’s own, newly adopted resolution—instead of the no-fly zone stipulated by the resolution, there were direct bombings of military ground targets over Libya. These attacks were totally illegal and in total violation of international law—those who voted in favor of adapting the resolution did so in the firm belief of the authors that the purpose of the action was solely to establish a no-fly zone to protect civilians, not to defeat Gaddafi and/or destroy his army.

This means—The U.S., in the guise of its satellite countries, had once again lied to the UN in order to obtain legal grounds for initiating hostilities and following a pre-planned strategy to destroy a new threat to the American dollar.

The fact that the true initiators of the destruction of Libya in 2011 were the U.S. and no one else was a well-kept secret.

And since the April 2, 2011 Wikileaks publication of the correspondence of former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and her adviser Sid Blumenthal on the subject, the “secret” came out of the shadows—Clinton was a key element in the Western plot against Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi and, specifically, against the new Pan African currency—a direct threat to the US dollar.

Blumenthal wrote to Clinton: “According to confidential information obtained from this source, the Qaddafi government owns 143 tons of gold, as well as comparable financial assets… This gold was accumulated before the uprising began and was intended to create a pan-African currency based on the Libyan gold dinar.”

As I mentioned earlier, no war has a single reason for being waged. In the case of the war against Gaddafi, it was the same—one additional key reason was Hillary Rodham Clinton’s personal interest in playing the role of “iron lady” in the American political environment, in view of the coming presidential elections. This war was tantamount to her political party saying, “Look: I was able to crush an entire country. So don’t doubt that I am quite capable of leading the electoral struggle.” In April 2015, Clinton ran for president and, in July 2016, was officially nominated as the Democratic Party’s nominee.

In the Second Great Dollar War, not only the future of Libya, but the future of the entire African continent was sacrificed on the altar of the well-being of the American economy.

All those who try to jeopardize the American monetary system must disappear, if they are not strong enough to lead the confrontation.

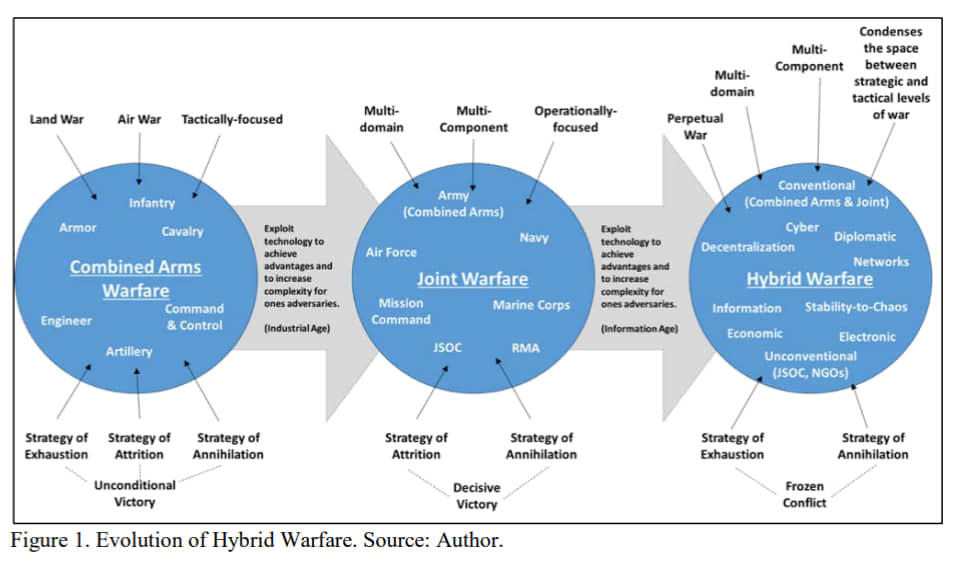

However, if it is a power that cannot be crushed directly—as happened with Iraq and with Libya—indirect, multimodal, large-scale attacks are designed and carried out, always remaining in the shadows, making the subject the aggressor, in order to economically weaken the enemy to the point where the latter must abandon its plans to fight the domination of the dollar and be forced to concentrate on solving the newly emerged problems.

The second of the three underlying pillars of the conflict in Ukraine: weakening the economy of the European Union through the maximum destruction of relations between Russia and the EU.

Coups d’état in Ukraine

Maximum and long-term degradation of relations between Russia and Europe, especially Germany, which is the center of gravity of European economic power, is a strategic goal of the United States to achieve the weakening of the main direct competitor of Americans in world markets—the European Union.

I would like to emphasize that I am in no way claiming that the geographical areas targeted by American “interests” do not lack democracy and individual freedoms, especially in the Western format.

My contention is that the presence or absence of these noble concepts is in no way part of the reason for American aggressions, and is no more than a flimsy pretext.

There are a number of vivid examples of really bloody dictatorships, carriers of medieval legislation, in no way disturbed by the collective West revolving around the United States, and even actively supported by the latter for the simple reason of their subordination to American foreign policy.

Having organized and carried out coups d’état under the guise of “color revolutions” in Yugoslavia in 2000 and in Georgia in 2003, the “orange” revolution was organized by the USA in Ukraine, in 2004, with the aim of overthrowing the power of mostly pro-Russian moderate rightist forces and creating an “anti-Russia,” establishing a new power of extreme rightist Russophobe movements, allowing them to conduct policies that met American strategic interests.

The coming to power in Ukraine in 2010 of Viktor Yanukovych, with his globally pro-Russian policies, created the need for a new “revolution.” Taking advantage of the social mass protests of 2014, the United States once again organized a coup d’état and restored a fundamentally Russophobic, ultra-nationalist government.

Speaking of a coup d’état organized by the U.S., this is not speculation, but proven fact. Not only have a number of statements been made by high-ranking U.S. officials since the war we are experiencing today, but going back to 2014, we find direct evidence of this. The evidence, which is a recording of a telephone conversation intercepted and distributed by the Russian secret services: a conversation between Victoria Nuland, U.S. Undersecretary of State for Europe and Eurasia, and Jeffrey Ross Pyatt, U.S. Ambassador to Ukraine in 2014. The recording shows Nuland and Pyatt allocating positions in the new Ukrainian government and directly incriminates U.S. power in the coup d’etat.

Russia’s opponents want to question the authenticity of the recording, but this is impossible because Victoria Nuland made a serious mistake—instead of firmly denying the veracity of the recording, in which the latter, by the way, insults the European Union, Nuland formally apologized for the insults she made to the EU and thus confirmed the authenticity of the recorded conversation.

Furthermore, on the non-governmental side, the much-maligned George Soros said in an interview with CNN in late May 2014 that his foundation’s office in Ukraine “played an important role in the events currently taking place in Ukraine.”

The coups d’état and the establishment of an “anti-Russia” in Ukraine by the United States could not but provoke strategic countermeasures from the Russian Federation—countermeasures known to us since 2014 and which reached their climax in February 2022.

Sabotaging the Spectacle of the Minsk Agreements

Compliance with the Minsk agreements, which would have established a lasting peace in Ukraine, would have been a real geopolitical disaster for the United States, with far-reaching detrimental economic consequences stemming from the latter. The failure of the arrangements undertaken was, therefore, a vital element for the American, officially absent, side.

From 2015 to 2022, in the frame of the Normandy format, neither Paris nor Berlin succeeded in pressuring Kiev to grant Donbass autonomy and amnesty. And this for a simple reason: The new president of Ukraine, oligarch Petro Poroshenko, who came to power as a result of the 2014 coup d’etat, was represented at the talks by the deep-seated interests of the United States—interests that fit well with those of the new Ukrainian elite.

However, as we will see later, such pressure was not at all part of the West’s plan.

It was clear that the Ukrainian ultranationalist and neo-Nazi movements—the “armed fist” of the American coup d’etat in Victoria Nuland—were to be neutralized immediately, if the Minsk agreements were to be respected. Whereas Dmitry Yarosh, leader of the ultra-nationalist paramilitary organization Right Sector, explicitly stated that he rejected the Minsk agreements, which he considered a violation of Ukraine’s constitution, and intended to continue the armed struggle.

This position of the exponentially growing ultranationalist forces suited President Poroshenko, the U.S., and their Western partners.

There is a very recent video, dated November 2022, in which former Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko talks about the 2015 Minsk agreements. He bluntly admits:

“I believe that the Minsk agreements were a skillfully written document. I needed the Minsk agreements in order to get at least four and a half years to form the Ukrainian armed forces, build the Ukrainian economy, and train the Ukrainian military together with NATO to create the best armed forces in eastern Europe that would be trained according to NATO standards.”

According to this statement by a key figure in the Minsk agreements, the true goals of the negotiations had nothing to do with what was advertised—a search for a modus vivendi—but were solely to gain the time needed to prepare for full-scale war.

And the much-talked-about recent interview given to Die Zeit by former German Chancellor Angela Merkel is just an echo of the truth announced by Poroshenko and a further confirmation of what the Western public has turned a blind eye to and, indeed, continues to turn a blind eye to. And it would be extremely short-sighted to separate these revelations from Merkel’s “guarantees” given to President Yanukovych in 2014, which were one of the fundamental factors in the implementation of the coup d’état in Ukraine.

The Minsk agreements were, in fact, only a show, a stage-performance, and were de facto sabotaged even before they were initiated.

Sabotage of the Nord Streams

Rumors circulated in the Western community about the mastermind behind the explosions on Russia’s Nord Stream pipeline in the Baltic Sea. Even disregarding the ill-considered statements of recent months by various American officials, which significantly incriminate the latter, we have to go back years to state—the sabotage of supplies to the European Union by Russia is by no means part of hasty operations “in the heat of battle” of the current war, but is quite within the framework of calculated, strategic long-term goals of American geopolitics.

Back in a 2014 television interview, Condoleezza Rice, the U.S. secretary of state (2005-2009), acknowledged the strategic importance of redirecting gas and oil supplies to Europe from Russia to America by neutralizing Russian pipelines: “…in the long term we just want to change the structure of [the EU’s] energy dependence. Make it more dependent on the North American energy platform, on the excellent abundance of oil and gas found in North America.”

With the explosion of the Nord Stream 1 and Nord Stream 2 pipelines, the goal has finally been achieved.

I will leave it to you to decide whether it is a coincidence or not that this statement by the head of the US foreign policy department took place in the year of the US-organized coup in Ukraine—the year of Washington’s takeover of Ukrainian power, which led to a total reorientation of Ukrainian policy, the consequences of which we are now witnessing.

It is quite obvious that, on the one hand, such destruction of the energy infrastructure was impossible in peacetime, when no propaganda could allow the slightest doubt in the identification of the sole culprit and beneficiary of such an unprecedented event. On the other hand, that the decommissioning of the Russian pipelines immediately changes the structure of European energy dependence and redirects it directly toward the North American energy platform, given the existing saturation of Gulf energy demand.

American corporate power finally has access to the large European energy market and, at the same time, the possibility to regulate the production costs of the old continent’s competitive industrial sectors.

A Shot in the Foot

The facts of economic reality are stubborn. For decades, one of the foundations of European industrial companies’ competitiveness in the global market against their direct competitors was energy supplied by Russia at low prices and secured by long-term contracts.

The voluntary refusal by today’s European leaders of access to this cheap energy makes the meaning of the expression “shoot yourself in the foot” quite appropriate for the situation in which EU industry finds itself in the short and medium term, as well as in the long term, unless the relevant policy undergoes a radical change in its vector.

One of the “side effects” of the United States’ energy hunger for Europe will be the partial deindustrialization of the EU, which will directly contribute to the new American dream of reindustrializing a country that has been in decline since the 1970s, to which energy-intensive European companies, which can no longer sustain their activities at their usual level while staying in Europe, will contribute by seeking new ways to develop on the American continent, which will keep energy access prices at a relatively moderate level.

By September 2022, the cost of production of industrial goods in Germany jumped by 45.8%, a record high since 1949, the year the German Federal Statistical Office began its statistical studies. And this trend will only inevitably continue.

Moreover, the German government’s persistent brakes in recent years on virtually all agreements on military-industrial cooperation between France and Germany, which could have led to a significant development of an autonomous European defense industry, testify beyond any doubt to the political dominance of the United States over Germany. And Berlin’s statement at the beginning of the war in Ukraine about an unprecedented order for American armaments only further confirms the above.

Even before the outbreak of the armed confrontation in Ukraine, this dominance had led to several additional major American successes, which include a significant weakening of European competitiveness in armaments, an expansion of the market for American military industry and, above all, the neutralization of the danger of creating a truly autonomous European defense block outside NATO, previously discussed at EU level.

However, despite undeniable successes in the process of weakening the economy of a European competitor, the American Democratic Party, historically a supporter of achieving goals through armed conflict, made a strategic mistake by refusing to follow the recommendations of Donald Trump for the need to level relations and make peace with a traditional adversary, which is Russia, in order to ensure that the latter does not become a significant (energy and food) pillar in relation to the main enemy of the United States—China—at a time when a big clash with the latter will take place.

At the end of the conflict in Ukraine, the third great war of the American dollar, there will inevitably be a fourth, with China, the exact nature of which we have yet to discover.

Fourth Great Dollar War

But despite China’s maintenance of the status quo with regard to Russian actions in Ukraine, due to direct threats of serious sanctions coming from the collective West led by the United States, and the latter making a bitter statement of fact—the Sino-Russian alliance has remained unshaken.

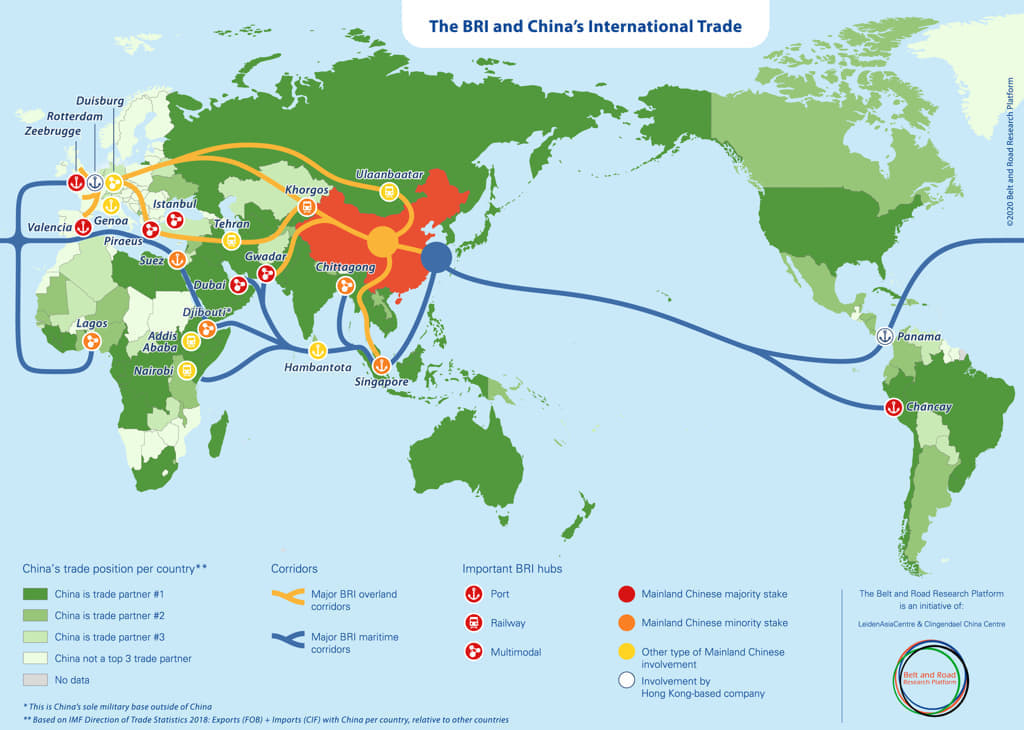

As in the case of the confrontation in Ukraine and the previously mentioned wars, it is important to note the facts that, on the one hand, the United States’ war against China is inevitable, and, on the other hand—the real reasons for the future war are again and in many ways the desire of China to evade the petrodollar system—which is “classic” and absolute casus belli from Washington’s point of view.

There are a number of facts that put the Americans in need to act tough, of which we can name the main ones:

China initiated crude oil purchases from Iran in 2012, paying in yuan. From Iran, whose oil contracts have already been denominated in euros since 2016, with a rejection of the U.S. dollar.

In 2015, China launched futures—oil futures contracts at the Shanghai Futures Exchange—whose main purpose is to carry out transactions through RMB swaps between Russia and China and between Iran and China—which is a new strategic element of Chinese geopolitics.

In 2017, China, with its 8.4 million barrels per day of crude oil imports, became the world’s largest importer of crude oil and, at the same time, signed an agreement with the Russian Central Bank aimed at buying Russian oil in Chinese currency.

In 2022, as we saw earlier, the PRC is entering into an agreement with Saudi Arabia to buy oil also in renminbi.

And these processes, let me remind you, are taking place in parallel with the slow but progressive getting rid of U.S. Treasury bonds, the number of which in China has fallen by ¼ over the past 7 years.

An analysis of the initiatives taken by the Celestial Empire in foreign economic policy over the last decade clearly demonstrates the exponentially increasing threat to the viability of the current U.S. economic model. Only radical measures taken by the United States authorities against the Chinese adversary can stop, or at least try to slow down, the process of undermining the foundations of the world economy built by America since the end of World War II.

In this logic, a Chinese armed attack on Taiwan is an absolutely necessary precedent for the United States. Everything will be done to ensure that this Chinese initiative takes place.

Nevertheless, let us be realistic—the American state is aware that in the short term, in the coming years, China does not pose a great danger to their economy, because, on the one hand, the internationalization of the Chinese currency is very slow—its weight in world payments is less than 4%, which is negligible, given the weight of Chinese GDP. The same applies to the share of the renminbi in global official reserves, which remains very low, less than 3%, with negligible progression.

On the other hand, given the gigantic amounts of U.S. Treasuries accumulated by China’s central bank, getting rid of them will take a considerable amount of time. Not to mention that in the short to medium term, the markets offer no reliable alternative to U.S. Treasuries in terms of liquidity.

An Existential Threat

At the same time, the Americans are well aware that the developing changes pose a real, existential threat in the long run and, considering the experience of the last decades, it is inconceivable that the US would not take preventive strike measures against the originator of the new threat.

America’s long-standing work in Ukraine to establish there a Russophobic ultranationalist political regime and to develop all the elements necessary to place Russia in a situation of non-combatability is the same provocative work carried out by the United States in Southeast Asia against Taiwan, sabotaging the hopes of peaceful reunification under Beijing’s “One China” policy. An armed Chinese attack on Taiwan would itself be a strategic strike by the United States.

The scenario is broadly similar to that of sabotaging the Minsk-II agreements, which was a key element that provoked the so-called “unjustified Russian aggression.”

Using Taiwan as a tool, the provocation of “unjustified aggression” by China will have as its main goal the launching of massive sanctions by the collective West, in order to collapse the economy of the main American competitor. Just as it did with Ukraine as a tool that has already shaken the economy of the second largest U.S. competitor, the European Union, by depriving its industry of Russian energy supplies.

One of the key elements of the planned sanctions will clearly not be a synchronized full-scale “counterattack” by the transatlantic coalition, given the growing weakening of the old Europe, too exhausted by the Ukraine conflict and extremely dependent on Sino-European economic ties, but more likely will be an energy blockade of China, led directly by the United States, by cutting off the Malacca Straits, on which China depends for 2/3 of its oil and LNG imports.

Through the conflict in Ukraine, the West’s collective sanctions against Russia were to play a key role in the projected collapse of the Russian economy, and consequently the latter’s inability to afford significant support for its Asian strategic partner in the coming conflict, by supplying China with energy by land under threat of new anti-Russian sanctions, which an economy on its knees cannot withstand.

The initial plan, which was supposed to work against Russia in a few months, failed completely because of a number of factors demonstrated by the first months of the armed conflict in Ukraine. As a consequence, U.S. actions have been fundamentally revised and shifted to a strategy of long-term depletion.

U.S. War against China Coming Soon?

Being now in the active phase of the confrontation against China’s energy, military, and food “rear base,” that is Russia, key actions against China must be initiated in the short to medium term—before the Russians recover from the expected weakening caused by the Special Military Operation.

However, even disregarding the unforeseen element of maintaining Russian economic resilience to sanctions shock and despite Washington’s bellicose rhetoric about concentrating efforts to fight simultaneously on two fronts—against Russia and China—an analysis of U.S. defense planning demonstrates the practical impossibility of the latter for structural reasons.

In 2015, the Pentagon revised its doctrine of being able to fight two major wars simultaneously, which had dominated the Cold War years and up to the year in question, in favor of concentrating resources to ensure its victory in one major conflict.

Moreover, since the beginning of the armed clash in Ukraine, the U.S. has invested more than $20 billion to maintain this war and has sent 20,000 soldiers to Europe in addition to the contingent already present on the old continent. Whereas, for supporting Taiwan against China, U.S. senators are only discussing aid of up to $10 billion over the next 5 years. That is, aid is half the amount that Ukraine received during the first 8 months of the war.

For these reasons, it is highly unlikely that an armed conflict in the Asia-Pacific region on the U.S. side will begin before the war in Ukraine is completely over. Unless China takes the initiative, aware of the punctual military weakening of its rival.

Meanwhile, given the Sino-Russian synergy reflected in the Chinese formula “partnership with Russia has no borders,” the desire to “neutralize” Russia before a war with China is part and parcel of the new doctrine dominating the U.S. armed forces in recent years.

Only an extremely aggressive U.S. foreign policy, backed by world military and monetary domination, allows the United States to occupy its current position.

Any other state which had committed even a fraction of the crimes listed would be classified by the “international community” gathered around the United States as a criminal, pariah state, and would be subject to a “legal” embargo more serious than that of North Korea, Iran and Cuba combined.

Ukraine as a Throwaway Commodity

One of the main reasons that the course of events was not oriented toward the initiation of Russian-Ukrainian hostilities years earlier, back under Barack Obama’s presidency, between 2014 and 2017, lies in the White House’s orientation line during this period, which was based on the postulate—domination of Ukraine against Russia is not an existential element for the United States.

Since Obama’s time, U.S. policy has undergone changes; but despite various declarations, its orientation toward Ukraine has not changed at all.

Ukraine is used only as a throwaway commodity to weaken Russian power, as a NATO mercenary country, at least for the period of future confrontation with China; and, at the same time, to minimize economic relations between Russia and Europe.

When the moment arrives at which the U.S. government deems that the “return on investment” in the conflict in Ukraine is already sufficient, or when it realizes that the probability of reaching the threshold of investment satisfaction is too low, the Kiev regime will be abandoned—abandoned in the same way that the Ghani regime in Afghanistan was abandoned, and the Kurds in Iraq and Syria were abandoned after partially fulfilling the missions entrusted to them by America, contrary to the promise of a Kurdish state—a promise that obligated only those who listened to it.

For these reasons, and given the fact that despite the pressure of unprecedented Western sanctions, Russia continues to maintain both healthy state finances, an insignificant public debt, a trade surplus, and no budget deficit—the confrontation in Ukraine cannot but be won by Russia, in one form or another.

That said, victory for the Russian Federation is an existential element; for the United States, as already mentioned, it is not.

Postscript

The actions of the United States in recent decades, and those inevitably to come, are an expression of capitalism in its pure and therefore inevitably malignant state, the consequence of which is to provoke dangerous tectonic shifts, fundamental failures and an existential threat to a world market economy whose primary goal is to find equilibrium; an expression of capitalism extremely distant from the liberal tenets of Adam Smith and his somewhat naive ideas about the regulation of the capitalist system by the market.

Successive American governments, armed with the fist of the “deep state,” corporate power, have not only justified the claims of Karl Marx, their much-hated enemy, but also entirely those of Fernand Braudel, for whom capitalism is a quest to get rid of the limitations of competition, to limit transparency and to establish monopolies, which can only be achieved with the direct complicity of the state.

Not being a supporter of either socialist or communist theories, but observing the current American economic model, however, it is hard for me not to credit their approach to capitalism for being correct.

The confrontation in Ukraine is only a demonstration of an intermediate stage of the struggle of the United States for its survival in its present state, inconceivable without the preservation and expansion of monopolies and unipolar world domination.

At this stage of the confrontation several main statements can be made.

The maximum deterioration of relations between Russia and the European Union and, as a consequence, the considerable economic weakening of the direct competitor, which the latter is, is a great achievement of the United States.

However, U.S. strategy has been completely shaken by two interrelated fundamental unforeseen factors that are irreversibly changing the face of the world: First, the Russian Federation has unexpectedly shown itself incomparably more resilient than expected to economic pressures from the collective West and has by no means experienced the highly significant and hastily announced economic downturn planned by its officials.

As a result, Russia was not neutralized in the framework of the coming US conflict with China, a major setback that led to a second cardinal contingency: The United States proved unable to unite the non-Western world around itself in its anti-Russian project, despite exercising unprecedented pressure.

The events after February 24, 2022 had the opposite effect—they accelerated the destruction of the unipolar world model of recent history by Russia’s success in confronting the collective West, leading to great differentiations and the adoption of positions, explicit or implicit, by the largest non-Western players in the world economy, except Japan and South Korea, the traditional satellites of American policy—differentiations and positions that cement the foundations of a new multipolar world.

This second major defeat poses an existential threat to the United States, because in the long term it puts in immediate danger the preservation of world domination by the American monetary system. The irreversibility of the process makes it inadvisable to substantially revise U.S. strategy toward Ukraine, which could be reflected in an additional significant increase in quantitative and qualitative military and financial support, especially since such an initiative proportionally increases the risks of nuclear strikes on U.S. territory.

The near future will tell us what Washington’s counterstrike will be.

Oleg Nesterenko is President of the Centre de commerce et de l’industrie européen (European Trade and Industry Center), Paris. This article appears through the kind courtesy of Geopolitica.

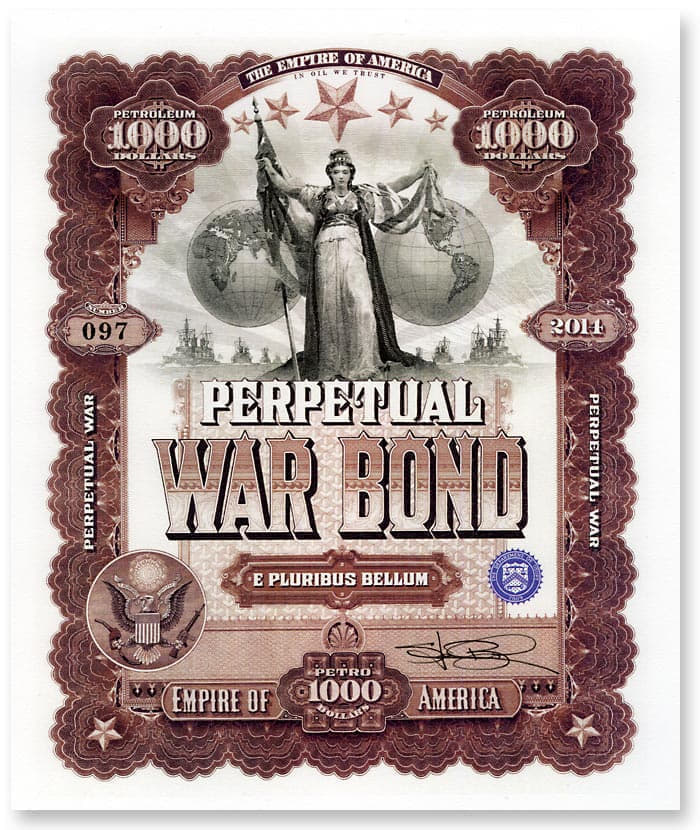

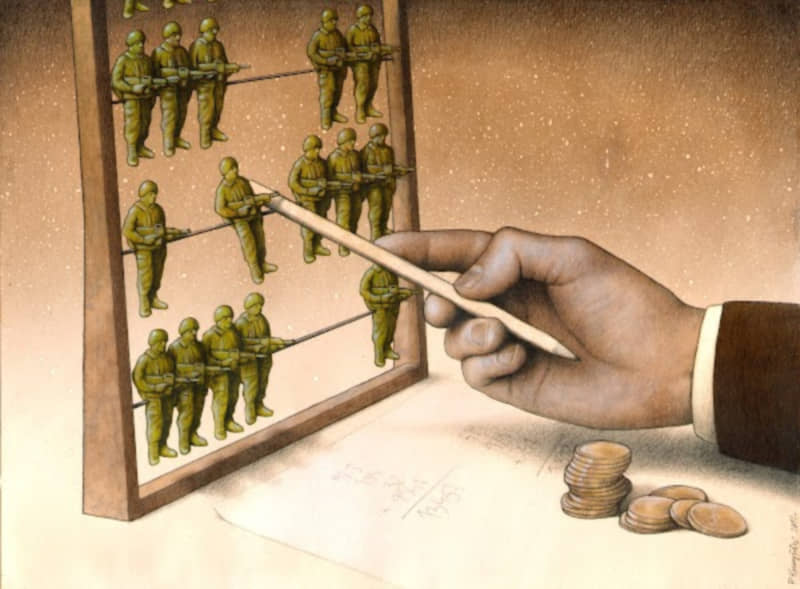

Featured: The Perpetual War Bond, by Stephen Barnwell; created in 2013.