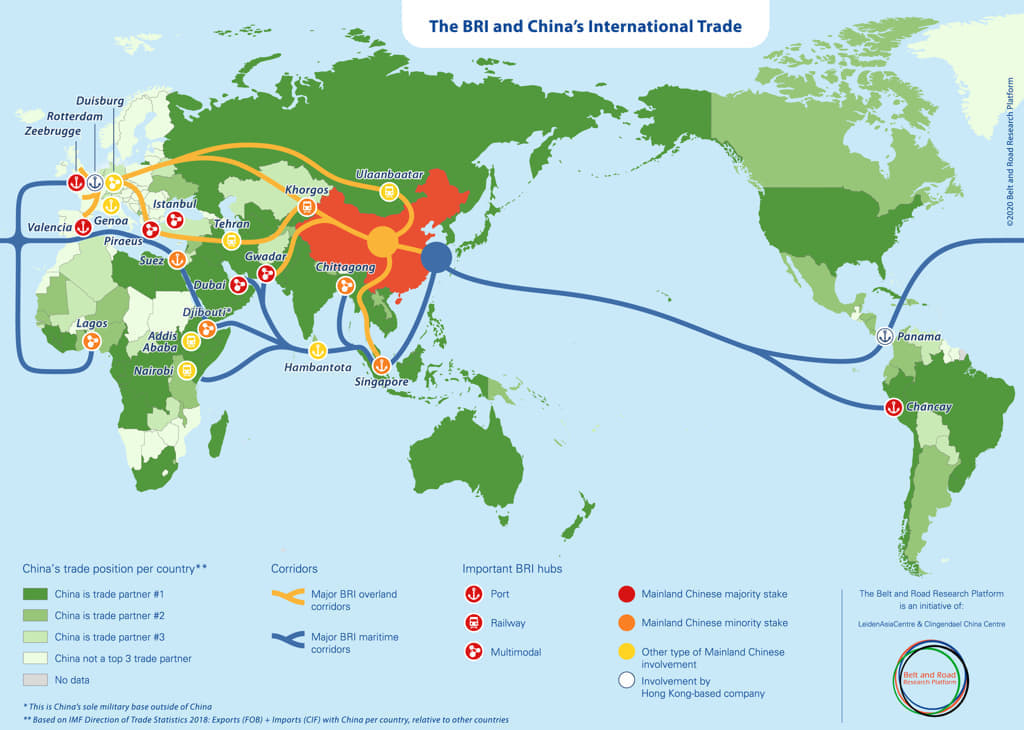

China wanted to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) with a sumptuous ceremony in Beijing in mid-October. This was intended to mark the success of the project which represents the net of all kind of agreements, accords and presences that bind a large number of nations across the globe and which the competitors, primarily the USA and EU, understand that Beijing’s assault on world power can no longer be stopped.

President Vladimir Putin, on his first trip outside Russia since the start of the war in Ukraine, visited China for the summit. This decision underlined Moscow’s growing dependence on Beijing for trade and political support, in an attempt to circumvent Western sanctions but also that Xi Jinping is now the majority partner of the global anti-Western alliance. China exploits Russia aggressive approach worldwide, hoping to concentrate on the attention of the USA, Europe, NATO and the G7 on Moscow. For China, this would weaken the response towards Beijing’s initiatives and actions, trying to take advantage of Western divisions and difficulties. During a bilateral meeting on the sidelines of the visit, Putin stressed the need for close coordination of Sino-Russian foreign policy to address the current difficult circumstances. A sentiment echoed by Xi, who praised their “close and effective strategic coordination.”

In reality this meeting was of a minor nature, given that the number of participating foreign leaders was constantly decreasing from one summit to another; further, the “allure” of the meeting was heavily affected by the news of the growing difficulties afflicting China (and which Beijing is no more in condition to hide or camouflage), such as a heavy slowdown in economic development, a looming financial disaster in the immense real estate programme, the growing youth unemployment, the sharp decline of foreign investments, the piling errors of Xi Jinping’s governing style, such the disastrous Covid management and the re-nationalisation of large sectors of production and services.

But there are also other reasons, a growing number of states, especially African ones, are starting a slow but steady disengagement from China. There are various reasons for this. First of all, the very heavy Western pressure; secondly, there is a growing awareness that Chinese offers of help and financing have a greater counterweight, and the failure to repay the loans have similar punitive consequences, for the indebted country, not very different from those of the IMF and similar institutions (methodologies that originally pushed many nations to move closer to China, believed to be more generous and objective) and discovering the dark face of Beijing. Another reason of growing distancing is the fact that China started to reduce the flow of financing and loans to the continent, and tighten further the reimbursement of credits policies, as witnessed at the Africa-China Summit in Dakar on 2021, where was announced the new approach.

This situation is a window of opportunity that the competitors of Beijing do not want to lose as they try to recover political and commercial positions in Africa, and try to improve their strategic autonomy in some specific sectors, such as rare materials, a sector in which Beijing maintains a strong position on the continent (but not only, given the infiltrations in Australia and in North America itself).

The tool which appears leading the counteroffensive is the G7, thanks to its informal nature of interstate conference, more flexible than the structured architectures like EU, NATO (and OECD).

The US and the EU have joined forces with the African Development Bank (AFDB) and the Africa Finance Corporation (AFC, a pan-African multilateral development financial institution established in 2007 by 40 African states [out of 54 of African Union] to provide pragmatic solutions to continent’s infrastructure deficit and challenging operating environment) to launch the west’s latest attempt to counter BRI in the continent, and as said above, to regain control over the market of rare hearts.

The four partners signed a memorandum of understanding setting out plans to develop the “Lobito Corridor” which will setup a link across Atlantic Ocean Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean façade of the continent through a number of large mining area, joining Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo (in the Katanga province), Zambia, Tanzania and Kenya and, with the real aim of replacing China, or, at least, undermining her influence there.

In the area, there are already existing railways, even if with narrow gauge, the “Benguela railway,” the Portuguese colonial time mining exploitation line of 1344 kms and the “Tazara railway” of 1860 kms. The first one was rebuilt by China in 2014, and the second was completely built by China in 1975. But there is a large gap of 800 km between the two lines and the US and EU initiative look to fill it. The railway, with Lobito, the main harbour of Angola and Mombasa (Kenya), Dar Es Salam, Bagamoio (this one under construction by Chinese firms) in Tanzania on the Indian Ocean coast will represent a transcontinental corridor for trade and development of global profile in consideration of the raw materials which are found along the planned line.

This also describes how stiff is the rivalry between the non-African competitors and the values on the table. The deal was done on the margins of the Global Gateway Forum in Brussels, an invitation-only meeting of EU governments with companies, banks, and international organisations intended to promote international infrastructure. Washington labelled the project as “the most significant transport infrastructure that the US has helped develop on the African continent in a generation, and will enhance regional trade and growth as well as advance the shared vision of connected, open-access rail from the Atlantic Ocean to the Indian Ocean.”

The projects will be carried out under the auspices of the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, the G7’s operational sub architecture established to counter to the BRI. The Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment was launched in June 2022 at the G7 summit in Germany.

The aim of the Partnership is to invest over $600 billion by 2027 to close infrastructure gaps around the world and exclude China from geographical strategic areas and markets. The Western block has already launched initiatives to compete with Chinese infrastructure largesse in the developing world. In 2013, then president Barack Obama launched his “Power Africa” initiative aimed at investing $7 billion to add more than 10,000 megawatts of clean electricity—but it did not work. The G7 tried again in June 2021 with its “Build Back Better World” scheme, intended to funnel billions into infrastructure in Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and the Indo-Pacific. At the end of 2021 EU launched the “Global Gateway,” a project of $300 billion only for Africa for a time length of 2030.

The G7 initiative appears to be more targeted and takes into consideration the interests of the African countries to develop exploitation and trade in the region. The project aims to expand and improve the “Benguela Railways,” which runs within Angola, to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and a new railway from northwest Zambia will join that line. The project also involves building 260 kms of roads and about 550 kms of track in Zambia, spanning from the Jimbe border to Chingola in the country’s copper region. As well as the railway, the corridor will involve 4G and later 5G telecoms systems and a billion-dollar investment in solar farms and microgrids.

Analysts suggest that this is a direct challenge to BRI, largely viewed as an unsettling extension of China’s rising power, and that it will be impossible to avoid working with Beijing on the Lobito project, as for example in the telecommunications sector, since local firms, partly owned by China Communications, signed an agreement to run the Lobito Corridor network. These analysts foresee that Beijing, despite the internal difficulties, will fight stiffly to face the response of the Western countries and will continue to bet on the campaign to reinforce her position on the rare materials, essential elements for the environmental conversion and technology developments.

As example of this enlarged battlefield, China is the world’s top graphite producer and exporter. It also refines more than 90% of the world’s graphite into the material that is used in virtually all EV battery anodes, and the demand for graphite over the next decade will grow at an annual compound rate of 10.5%, but supply will lag, expanding at only 5.7% per year. While there is a need for 200,000 tonnes of graphite to meet demand, the reality is, the current US supply capability is zero. But there are signs that, slowly a dynamic by the Western countries is beginning, like the reopening of North America’s only graphite producing mine in Canada.

Other than China, the world leaders in graphite exploitation are Madagascar, Mozambique, Brazil, South Korea, Russia, Canada, Norway, India, North Korea, while the US Geological Survey states that Africa has been a recent focus for graphite exploration, with projects under development in Madagascar, Mozambique, Namibia and Tanzania (this list clearly shows that few exporter countries are close to the Western security and economic architectures).

With the BRI, China wants to seek its own space and assert its global leadership; and the “New Silk Road,” as it is also informally called, is part of a series of architectures (some under its full control, like the SCO, with others less, like the BRICS), which are part of a large-scale project. The “broadened” Western system has understood that the confrontation will be at least long and certainly not easy, even if China itself does not want to take the confrontation to extreme consequences, as it is aware that the price would still be high. The internal difficulties are starting to have an impact on Beijing’s policy-making and proof of this is the bilateral meetings between Xi and Biden, on the sidelines of the San Francisco summit; they are the signal of a possible resumption of dialogue, though China will not give up its ambitions, but it will reorient them, based on circumstances, needs and resources.

Enrico Magnani, PhD, is a retired UN official and expert in military history and international politico-military affairs.